The Question of Representativeness

How confident can we be that the results of social psychology studies generalize to the wider population if study participants are largely of the WEIRD variety? [Image: Mike Miley, http://goo.gl/NtvlU8, CC BY-SA 2.0, http://goo.gl/eH69he]

Along with our counterparts in the other areas of psychology, social psychologists have been guilty of largely recruiting samples of convenience from the thin slice of humanity—students—found at universities and colleges (Sears, 1986). This presents a problem when trying to assess the social mechanics of the public at large. Aside from being an overrepresentation of young, middle-class Caucasians, college students may also be more compliant and more susceptible to attitude change, have less stable personality traits and interpersonal relationships, and possess stronger cognitive skills than samples reflecting a wider range of age and experience (Peterson & Merunka, 2014; Visser, Krosnick, & Lavrakas, 2000). Put simply, these traditional samples (college students) may not be sufficiently representative of the broader population. Furthermore, considering that 96% of participants in psychology studies come from western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries (so-called WEIRD cultures; Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010), and that the majority of these are also psychology students, the question of non-representativeness becomes even more serious.

Of course, when studying a basic cognitive process (like working memory capacity) or an aspect of social behavior that appears to be fairly universal (e.g., even cockroaches exhibit social facilitation!), a non-representative sample may not be a big deal. However, over time research has repeatedly demonstrated the important role that individual differences (e.g., personality traits, cognitive abilities, etc.) and culture (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism) play in shaping social behavior. For instance, even if we only consider a tiny sample of research on aggression, we know that narcissists are more likely to respond to criticism with aggression (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998); conservatives, who have a low tolerance for uncertainty, are more likely to prefer aggressive actions against those considered to be “outsiders” (de Zavala et al., 2010); countries where men hold the bulk of power in society have higher rates of physical aggression directed against female partners (Archer, 2006); and males from the southern part of the United States are more likely to react with aggression following an insult (Cohen et al., 1996).

Ethics in Social Psychological Research

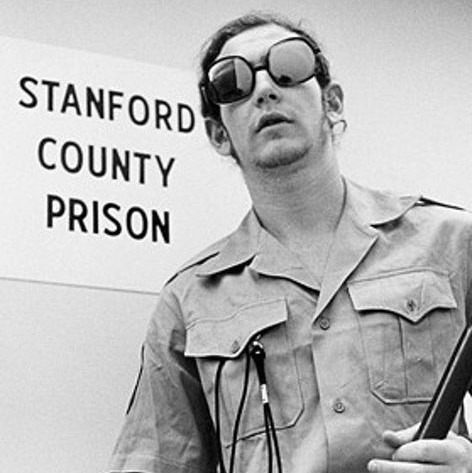

For better or worse (but probably for worse), when we think about the most unethical studies in psychology, we think about social psychology. Imagine, for example, encouraging people to deliver what they believe to be a dangerous electric shock to a stranger (with bloodcurdling screams for added effect!). This is considered a “classic” study in social psychology. Or, how about having students play the role of prison guards, deliberately and sadistically abusing other students in the role of prison inmates. Yep, social psychology too. Of course, both Stanley Milgram’s (1963) experiments on obedience to authority and the Stanford prison study (Haney et al., 1973) would be considered unethical by today’s standards, which have progressed with our understanding of the field. Today, we follow a series of guidelines and receive prior approval from our institutional research boards before beginning such experiments. Among the most important principles are the following:

- Informed consent: In general, people should know when they are involved in research, and understand what will happen to them during the study (at least in general terms that do not give away the hypothesis). They are then given the choice to participate, along with the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time. This is precisely why the Facebook emotional contagion study discussed earlier is considered ethically questionable. Still, it’s important to note that certain kinds of methods—such as naturalistic observation in public spaces, or archival research based on public records—do not require obtaining informed consent.

- Privacy: Although it is permissible to observe people’s actions in public—even without them knowing—researchers cannot violate their privacy by observing them in restrooms or other private spaces without their knowledge and consent. Researchers also may not identify individual participants in their research reports (we typically report only group means and other statistics). With online data collection becoming increasingly popular, researchers also have to be mindful that they follow local data privacy laws, collect only the data that they really need (e.g., avoiding including unnecessary questions in surveys), strictly restrict access to the raw data, and have a plan in place to securely destroy the data after it is no longer needed.

- Risks and Benefits: People who participate in psychological studies should be exposed to risk only if they fully understand the risks and only if the likely benefits clearly outweigh those risks. The Stanford prison study is a notorious example of a failure to meet this obligation. It was planned to run for two weeks but had to be shut down after only six days because of the abuse suffered by the “prison inmates.” But even less extreme cases, such as researchers wishing to investigate implicit prejudice using the IAT, need to be considerate of the consequences of providing feedback to participants about their nonconscious biases. Similarly, any manipulations that could potentially provoke serious emotional reactions (e.g., the culture of honor study described above) or relatively permanent changes in people’s beliefs or behaviors (e.g., attitudes towards recycling) need to be carefully reviewed by the IRB.

- Deception: Social psychologists sometimes need to deceive participants (e.g., using a cover story) to avoid demand characteristics by hiding the true nature of the study. This is typically done to prevent participants from modifying their behavior in unnatural ways, especially in laboratory or field experiments. For example, when Milgram recruited participants for his experiments on obedience to authority, he described it as being a study of the effects of punishment on memory! Deception is typically only permitted (a) when the benefits of the study outweigh the risks, (b) participants are not reasonably expected to be harmed, (c) the research question cannot be answered without the use of deception, and (d) participants are informed about the deception as soon as possible, usually through debriefing.

- Debriefing: This is the process of informing research participants as soon as possible of the purpose of the study, revealing any deceptions, and correcting any misconceptions they might have as a result of participating. Debriefing also involves minimizing harm that might have occurred. For example, an experiment examining the effects of sad moods on charitable behavior might involve inducing a sad mood in participants by having them think sad thoughts, watch a sad video, or listen to sad music. Debriefing would therefore be the time to return participants’ moods to normal by having them think happy thoughts, watch a happy video, or listen to happy music.

Conclusion

As an immensely social species, we affect and influence each other in many ways, particularly through our interactions and cultural expectations, both conscious and nonconscious. The study of social psychology examines much of the business of our everyday lives, including our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors we are unaware or ashamed of. The desire to carefully and precisely study these topics, together with advances in technology, has led to the development of many creative techniques that allow researchers to explore the mechanics of how we relate to one another. Consider this your invitation to join the investigation.

Exercises & Critical Thinking

- How would you feel if you learned that you had been a participant in a naturalistic observation study (without explicitly providing your consent)? How would you feel if you learned during a debriefing procedure that you have a stronger association between the concept of violence and members of visible minorities? Can you think of other examples of when following principles of ethical research create challenging situations?

- Can you think of an attitude (other than those related to prejudice) that would be difficult or impossible to measure by asking people directly?

Click the Next Button to continue with Chapter 1.

Glossary

- Demand characteristics

- Subtle cues that make participants aware of what the experimenter expects to find or how participants are expected to behave.

- Samples of convenience

- Participants that have been recruited in a manner that prioritizes convenience over representativeness.

- WEIRD cultures

- Cultures that are western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic.

References

- Archer, J. (2006). Cross-cultural differences in physical aggression between partners: A social-role analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 133-153. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_3

- Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 219-229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219

- Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F. & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An “experimental ethnography.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 945-960. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.945

- Haney, C., Banks, C., & Zimbardo, P. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminology and Penology, 1, 69-97.

- Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), 371–378. doi: 10.1037/h0040525

- Peterson, R. A., & Merunka, D. R. (2014). Convenience samples of college students and research reproducibility. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 1035-1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.010

- Sears, D. O. (1986). College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on social psychology’s view of human nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(3), 515-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.3.515

- Visser, P. S., Krosnick, J. A., & Lavrakas, P. (2000). Survey research. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social psychology (pp. 223-252). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- de Zavala, A. G., Cislak, A., & Wesolowska, E. (2010). Political conservatism, need for cognitive closure, and intergroup hostility. Political Psychology, 31(4), 521-541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00767.x

Candela Citations

- Authored by: Rajiv Jhangiani. Provided by: Noba textbook series: Psychology. Located at: . License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike