An Introduction to the Science of Social Psychology

Now that you have some sense of the background story let’s have a look at our Quest Map (the way in which social psychologists examine). This map is a little rough right now and we’ll be filling it in as we go, but even a rough map gives you an idea of where you’re going!

(Map montage music plays in the background…)

Chapter Learning Objectives

The material in this section help you to achieve these learning objectives.

- Define social psychology and understand how it is different from other areas of psychology.

- Understand “levels of analysis” and why this concept is important to science.

We live in a world where, increasingly, people of all backgrounds have smart phones. In economically developing societies, cellular towers are often less expensive to install than traditional landlines. In many households in industrialized societies, each person has his or her own mobile phone instead of using a shared home phone. As this technology becomes increasingly common, curious researchers have wondered what effect phones might have on relationships. Do you believe that smart phones help foster closer relationships? Or do you believe that smart phones can hinder connections? In a series of studies, researchers have discovered that the mere presence of a mobile phone lying on a table can interfere with relationships. In studies of conversations between both strangers and close friends—conversations occurring in research laboratories and in coffee shops—mobile phones appeared to distract people from connecting with one another. The participants in these studies reported lower conversation quality, lower trust, and lower levels of empathy for the other person (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2013). This is not to discount the usefulness of mobile phones, of course. It is merely a reminder that they are better used in some situations than they are in others. It is also a real-world example of how social psychology can help produce insights about the ways we understand and interact with one another.

Social psychology is interested in how other people affect our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Researchers study group interactions, the way culture shapes our thinking, and even how technology impacts human relationships. What factors might influence the behavior of this couple? [Image: Matthew G, https://goo.gl/En2JSi, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7]

Social psychology is the branch of psychological science mainly concerned with understanding how the presence of others affects our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Just as clinical psychology focuses on mental disorders and their treatment, and developmental psychology investigates the way people change across their lifespan, social psychology has its own focus. As the name suggests, this science is all about investigating the ways groups function, the costs and benefits of social status, the influences of culture, and all the other psychological processes involving two or more people.

Social psychology is such an exciting science precisely because it tackles issues that are so familiar and so relevant to our everyday life. Humans are “social animals.” Like bees and deer, we live together in groups. Unlike those animals, however, people are unique, in that we care a great deal about our relationships. In fact, a classic study of life stress found that the most stressful events in a person’s life—the death of a spouse, divorce, and going to jail—are so painful because they entail the loss of relationships (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). We spend a huge amount of time thinking about and interacting with other people, and researchers are interested in understanding these thoughts and actions. Giving up a seat on the bus for another person is an example of social psychology. So is disliking a person because he is wearing a shirt with the logo of a rival sports team. Flirting, conforming, arguing, trusting, competing—these are all examples of topics that interest social psychology researchers.

At times, science can seem abstract and far removed from the concerns of daily life. When neuroscientists discuss the workings of the anterior cingulate cortex, for example, it might sound important. But the specific parts of the brain and their functions do not always seem directly connected to the stuff you care about: parking tickets, holding hands, or getting a job. Social psychology feels so close to home because it often deals with universal psychological processes to which people can easily relate. For example, people have a powerful need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). It doesn’t matter if a person is from Israel, Mexico, or the Philippines; we all have a strong need to make friends, start families, and spend time together. We fulfill this need by doing things such as joining teams and clubs, wearing clothing that represents “our group,” and identifying ourselves based on national or religious affiliation. It feels good to belong to a group. Research supports this idea. In a study of the most and least happy people, the differentiating factor was not gender, income, or religion; it was having high-quality relationships (Diener & Seligman, 2002). Even introverts report being happier when they are in social situations (Pavot, Diener & Fujita, 1990). Further evidence can be found by looking at the negative psychological experiences of people who do not feel they belong. People who feel lonely or isolated are more vulnerable to depression and problems with physical health (Cacioppo, & Patrick, 2008).

The feelings we experience as members of groups – as teammates, fellow citizens, followers of a particular faith – play a huge role in our identities and in our happiness. [Image: leonardo samrani, https://goo.gl/jHVWXR, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7]

Social Psychology is a Science

The need to belong is also a useful example of the ways the various aspects of psychology fit together. Psychology is a science that can be sub-divided into specialties such as “abnormal psychology” (the study of mental illness) or “developmental psychology” (the study of how people develop across the life span). In daily life, however, we don’t stop and examine our thoughts or behaviors as being distinctly social versus developmental versus personality-based versus clinical. In daily life, these all blend together. For example, the need to belong is rooted in developmental psychology. Developmental psychologists have long paid attention to the importance of attaching to a caregiver, feeling safe and supported during childhood, and the tendency to conform to peer pressure during adolescence. Similarly, clinical psychologists—those who research mental disorders– have pointed to people feeling a lack of belonging to help explain loneliness, depression, and other psychological pains. In practice, psychologists separate concepts into categories such as “clinical,” “developmental,” and “social” only out of scientific necessity. It is easier to simplify thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in order to study them. Each psychological sub-discipline has its own unique approaches to research. You may have noticed that this is almost always how psychology is taught, as well. You take a course in personality, another in human sexuality, and a third in gender studies, as if these topics are unrelated. In day-to-day life, however, these distinctions do not actually exist, and there is heavy overlap between the various areas of psychology.

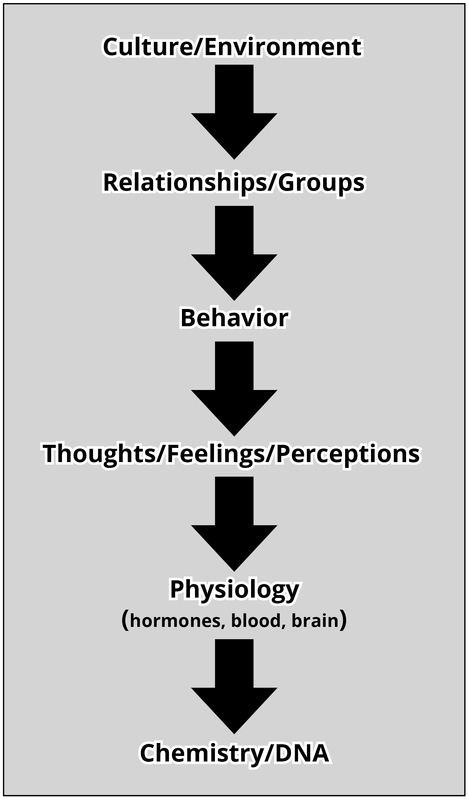

Figure 1 – The levels of analysis in psychology.

In psychology, there are varying levels of analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the different levels at which scientists might understand a single event. Take the example of a toddler watching her mother make a phone call: the toddler is curious, and is using observational learning to teach herself about this machine called a telephone. At the most specific levels of analysis, we might understand that various neurochemical processes are occurring in the toddler’s brain. We might be able to use imaging techniques to see that the cerebellum, among other parts of the brain, is activated with electrical energy. If we could “pull back” our scientific lens, we might also be able to gain insight into the toddler’s own experience of the phone call. She might be confused, interested, or jealous. Moving up to the next level of analysis, we might notice a change in the toddler’s behavior: during the call she furrows her brow, squints her eyes, and stares at her mother and the phone. She might even reach out and grab at the phone. At still another level of analysis, we could see the ways that her relationships enter into the equation. We might observe, for instance, that the toddler frowns and grabs at the phone when her mother uses it, but plays happily and ignores it when her stepbrother makes a call. All of these chemical, emotional, behavioral, and social processes occur simultaneously. None of them is the objective truth. Instead, each offers clues into better understanding what, psychologically speaking, is happening.

Social psychologists attend to all levels of analysis but—historically—this branch of psychology has emphasized the higher levels of analysis. Researchers in this field are drawn to questions related to relationships, groups, and culture. This means that they frame their research hypotheses in these terms. Imagine for a moment that you are a social researcher. In your daily life, you notice that older men on average seem to talk about their feelings less than do younger men. You might want to explore your hypothesis by recording natural conversations between males of different ages. This would allow you to see if there was evidence supporting your original observation. It would also allow you to begin to sift through all the factors that might influence this phenomenon: What happens when an older man talks to a younger man? What happens when an older man talks to a stranger versus his best friend? What happens when two highly educated men interact versus two working class men? Exploring each of these questions focuses on interactions, behavior, and culture rather than on perceptions, hormones, or DNA.

Social psychologists have developed unique methods for studying attitudes and behaviors that help answer questions that may not be possible to answer in a laboratory. Naturalistic observation of real world interactions, for example, would be a method well suited for understanding more about men and how they share their feelings. [Image: Michael Coghlan, https://goo.gl/dGc3JV, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/rxiUsF]

In part, this focus on complex relationships and interactions is one of the things that makes research in social psychology so difficult. High quality research often involves the ability to control the environment, as in the case of laboratory experiments. The research laboratory, however, is artificial, and what happens there may not translate to the more natural circumstances of life. This is why social psychologists have developed their own set of unique methods for studying attitudes and social behavior. For example, they use naturalistic observation to see how people behave when they don’t know they are being watched. Whereas people in the laboratory might report that they personally hold no racist views or opinions (biases most people wouldn’t readily admit to), if you were to observe how close they sat next to people of other ethnicities while riding the bus, you might discover a behavioral clue to their actual attitudes and preferences.

Click the Next Button to continue with Chapter 1.

Glossary

- Hypothesis

- A possible explanation that can be tested through research.

- Levels of analysis

- Complementary views for analyzing and understanding a phenomenon.

- Need to belong

- A strong natural impulse in humans to form social connections and to be accepted by others.

- Observational learning

- Learning by observing the behavior of others.

- Research confederate

- A person working with a researcher, posing as a research participant or as a bystander.

- Research participant

- A person being studied as part of a research program.

- The branch of psychological science that is mainly concerned with understanding how the presence of others affects our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Candela Citations

- Chapter. Authored by: Cynthia Lonsbary. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Chapter from NOBA project. Authored by: Robert Biswas-Diener. Located at: http://noba.to/s64y5c2m. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Quest Map. Authored by: Max Pixel. Located at: https://www.maxpixel.net/X-Marks-The-Spot-Pirate-Treasure-Quest-Map-309928. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright