TRANSLATED BY

ANNIE SHEPLEY OMORI AND KOCHI DOI

Professor in the Imperial University, Tokio

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

AMY LOWELL

And with Illustrations

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1920

COURT LADY’S FULL DRESS IN THE HEIAN PERIOD — (For explanation see List of Illustrations)

TRANSLATORS’ NOTE

The poems in the text, slight and occasional as they are, depending often for their charm on plays upon words of two meanings, or on the suggestions conveyed to the Japanese mind by a single word, have presented problems of great difficulty to the translators, not perfectly overcome.

Izumi Shikibu’s Diary is written with extreme delicacy of treatment. English words and thought seem too downright a medium into which to render these evanescent, half-expressed sentences and poems—vague as the misty mountain scenery of her country, with no pronouns at all, and without verb inflections. The shy reserve of the lady’s written record has induced the use of the third person as the best means of suggesting it.

Of the “Sarashina Diary” there exist a few manuscript copies, and three or four publications of the text. Some of them are confused and unreadably incoherent. The present translation was done by comparing all the texts accessible, and is especially founded on the connected text by Mr. Sakine, professor of the Girls’ Higher Normal School, Tokio, published by Meiji Shoin, Itchome Nishiki-cho, Kanda-ku, Tokio. As far as possible the exact meaning has been adhered to, and the words chosen to express it have been kept absolutely simple, without complexity of thought, for such is the vocabulary in which it was written. Sometimes the diarist uses the present tense, sometimes the text seems reminiscent. The words in square brackets have been inserted by the translators to complete the sense in English of sentences which literally rendered do not carry with them the suggestion of the Japanese text.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

COURT LADY’S FULL DRESS IN THE HEIAN PERIOD Colored Frontispiece

From Kokushi Daijiten, by kind permission of Mr. H. Yoshikawa. The figure was drawn for the purpose of showing the details of dress and therefore gives no indication of the grace and elegance of the costume as worn. It shows the red karaginu, or over-garment; the dark-green robe trimmed with folds, called the uchigi; the saishi, or head-ornament, in this case of gold but sometimes of silver; the unlined under-garment of thin silk; the red hakama, or divided skirt; and the train of white silk painted or stained in colors.

“IT WAS ALL IN FLOWER AND YET NO TIDINGS FROM HER”

KICHŌ: FRONT AND BACK VIEWS

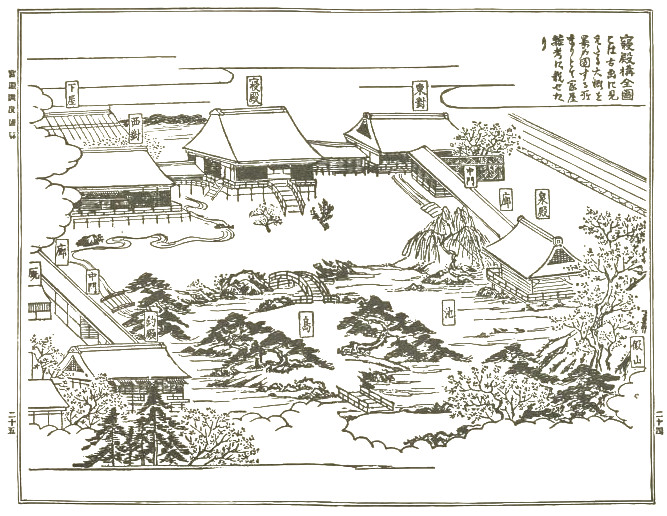

A NOBLEMAN’S HOUSE AND GROUNDS IN THE AZUMAYA STYLE:

PLAN OF BUILDINGS AND GARDEN

THREE KICHŌ PUT TOGETHER

OLD PRINT OF A NOBLEMAN’S DWELLING IN THE AZUMAYA STYLE

From an old book.

COURT DRESS OF MILITARY OFFICIAL (in color)

From Kokushi Daijiten, by kind permission of Mr. H. Yoshikawa. The figure shows the zui, or ornament of the head-strap holding the head-dress in place; also the method of rolling up the gauze flap of the head-dress. Tucked into the red state coat appear a half-spread fan and some folded sheets of paper, and at the back is seen a quiver made of lacquered wood. Underneath the red coat the hakama is shown. The shoes are of Chinese pattern.

ROYAL DAIS AND KICHŌ, SUDARÉ, ETC.

From old prints.

A NOBLEMAN’S CARRIAGE

SCREENED DAIS PREPARED FOR ROYALTY

From a print in an old book.

“HIS HIGHNESS CAME IN A HUMBLE PALANQUIN”

“THE LADY GOT UP AND SAW THE MISTY SKY”

“STRANGELY WET ARE THE SLEEVES OF THE ARM-PILLOW”

“IN THE DAYTIME COURTIERS CAME TO SEE HIM”

INTRODUCTION

BY AMY LOWELL

The Japanese have a convenient method of calling their historical periods by the names of the places which were the seats of government while they lasted. The first of these epochs of real importance is the Nara Period, which began A.D. 710 and endured until 794; all before that may be classed as archaic. Previous to the Nara Period, the Japanese had been a semi-nomadic race. As each successive Mikado came to the throne, he built himself a new palace, and founded a new capital; there had been more than sixty capitals before the Nara Period. Such shifting was not conducive to the development of literature and the arts, and it was not until a permanent government was established at Nara that these began to flourish. This is scarcely the place to trace the history of Japanese literature, but fully to understand these charming “Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan,” it is necessary to know a little of the world they lived in, to be able to feel their atmosphere and recognize their allusions.

We know a good deal about Japan to-day, but the Japan with which we are familiar only slightly resembles that of the Diaries. Centuries of feudalism, of “Dark Ages,” have come between. We must go behind all this and begin again. We have all heard of the “Forty-seven Ronins” and the Nō Drama, of Shōguns, Daimios, and Samurais, and many of us live in daily communion with Japanese prints. It gives us pause to reflect that the earliest of these things is almost as many centuries ahead of the Ladies as it is behind us. “Shōgun” means simply “General,” and of course there were always generals, but the power of the Shōguns, and the military feudalism of which the Daimios and their attendant Samurais were a part, did not really begin until the middle of the twelfth century and did not reach its full development until the middle of the fourteenth; the Nō Drama started with the ancient religious pantomimic dance, the Kagura, but not until words were added in the fourteenth century did it become the Nō; and block colour printing was first practised in 1695, while such famous print artists as Utamaro, Hokusai, and Hiroshige are all products of the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries. To find the Ladies behind the dark military ages, we must go back a long way, even to the century before their own, and so gain a sort of perspective for them and their time.

Chinese literature and civilization were introduced into Japan somewhere between 270 and 310 A.D., and Buddhism followed in 552. Of course, all such dates must be taken with a certain degree of latitude; Oriental historians are anything but precise in these matters. Chinese influence and Buddhism are the two enormous facts to be reckoned with in understanding Japan, and considering what an effect they have had, it is not a little singular that Japan has always been able to preserve her native character. To be sure, Shintoism was never displaced by Buddhism, but the latter made a tremendous appeal to the Japanese temperament, as the Diaries show. In fact, it was not until the Meiji Period (1867-1912) that Shintoism was again made the state religion. With the introduction of Chinese civilization came the art of writing, when is not accurately known, but printing from movable blocks followed from Korea in the eighth century. As was inevitable under the circumstances, Chinese came to be considered the language of learning. Japanese scholars wrote in Chinese. All the “serious” books—history, theology, science, law—were written in Chinese as a matter of course. But, in 712, a volume called “Records of Ancient Matters” was compiled in the native tongue. It is the earliest book in Japanese now extant.

If the scholars wrote in a borrowed language, the poets knew better. They wrote in their own, and the poetry of the Nara Period has been preserved for us in an anthology, the “Manyoshu” or “Collection of One Thousand Leaves.” This was followed at the beginning of the tenth century by the “Kokinshu” (“Ancient and Modern Poems”), to which, however, the editor, Tsurayuki, felt obliged to write a Chinese preface. The Ladies of the Diaries were extremely familiar with these volumes, their own writings are full of allusions to poems contained in them; Sei-Shōnagon, writing early in the eleventh century, describes a young lady’s education as consisting of writing, music, and the twenty volumes of the “Kokinshu.” So it came about that while learned gentlemen still continued to write in Chinese, poetry, fiction, diaries, and desultory essays called “Zui-hitsu” (Following the Pen) were written in Japanese.

Now the position of women at this time was very different from what it afterwards became in the feudal period. The Chinese called Japan the “Queen Country,” because of the ascendancy which women enjoyed there. They were educated, they were allowed a share of inheritance, and they had their own houses. It is an extraordinary and important fact that much of the best literature of Japan has been written by women. Three of these most remarkable women are the authors of the Diaries; a fourth to be named with them, Sei-Shōnagon, to whom I have just referred, was a contemporary.

In 794, the capital was moved from Nara to Kiōto, which was given the name of “Heian-jo” or “City of Peace,” and with the removal, a new period, the Heian, began. It lasted until 1186, and our Ladies lived in the very middle of it.

By this time Japan was thoroughly civilized; she was, indeed, a little over-civilized, a little too fined down and delicate. At least this is true of all that life which centred round the court at Kiōto. To historians the Heian Period represents the rise and fall of the Fujiwara family. This powerful family had served the Mikados from time out of mind as heads of the Shinto priests, and after the middle of the seventh century, they became ministers or prime ministers. An immense clan, they gradually absorbed all the civil offices in the Kingdom, while the military offices were filled by the Taira and Minamoto families. It was the rise of these last as the Fujiwara declined which eventually led to the rule of the Shōguns and the long centuries of feudalism and civil war. But in the middle of the Heian Period the Fujiwara were very much everywhere. Most of those Court ladies who were the authors of remarkable books were the daughters of governors of provinces, and that meant Fujiwaras to a greater or lesser degree. At that time polygamy flourished in Japan, and the family had grown to a prodigious size. Since a civil office meant a post for a Fujiwara, many of them were happily provided for, but they were so numerous that they outnumbered the legitimate positions and others had to be created to fill the demand. The Court was full of persons of both sexes holding sinecures, with a great deal of time on their hands and nothing to do in it but write poetry, which they did exceedingly well, and attend the various functions prescribed by etiquette. Ceremonials were many and magnificent, and poetry writing became, not only a game, but a natural adjunct to every possible event. The Japanese as a nation are dowered with a rare and exquisite taste, and in the Heian Period taste was cultivated to an amazing degree. Murasaki Shikibu records the astounding pitch to which it had reached in a passage in her diary. Speaking of the Mikado’s ladies at a court festivity, she says of the dress of one of them: “One had a little fault in the colour combination at the wrist opening. When she went before the Royal presence to fetch something, the nobles and high officials noticed it. Afterwards Lady Saisho regretted it deeply. It was not so bad; only one colour was a little too pale.”

That passage needs no comment; it is completely illuminating. It is a paraphrase of the whole era.

Kiōto was a little city, long one way by some seventeen thousand odd feet, or about three and a third miles, wide the other by fifteen thousand, or approximately another three miles, and it is doubtful if the space within the city wall was ever entirely covered by houses. The Palace was built in the so-called Azumaya style, a form of architecture which was also followed in noblemen’s houses. The roof, or rather roofs, for there were many buildings, was covered with bark, and, inside, the divisions into rooms were made by different sorts of moving screens. At the period of the Diaries, the reigning Mikado, Ichijo, had two wives: Sadako, the first queen, was the daughter of a previous prime minister, Michitaka, a Fujiwara, of course; the other, Akiko, daughter of Michinaga, the prime minister of the Diaries and a younger brother of Michitaka, was second queen or Chūgū. These queens each occupied a separate house in the Palace. Kokiden was the name of Queen Sadako’s house; Fujitsubu the name of Queen Akiko’s. The rivalry between these ladies was naturally great, and extended even to their entourage. Each strove to surround herself with ladies who were not only beautiful, but learned. The bright star of Queen Sadako’s court was Sei-Shōnagon, the author of a remarkable book, the “Makura no Sōshi” or “Pillow Sketches,” while Murasaki Shikibu held the same exalted position in Queen Akiko’s.

We are to imagine a court founded upon the Chinese model, but not nearly so elaborate. A brilliant assemblage of persons all playing about a restricted but very bright centre. From it, the high officials went out to be governors of distant provinces, and the lesser ones followed them to minor posts, but in spite of the distinction of such positions, distance and the inconvenience of travelling made the going a sort of laurelled banishment. These gentlemen left Kiōto with regret and returned with satisfaction. But the going, and the years of residence away, was one of the commonplaces of social life. Fujiwara though one might be, one often had to wait and scheme for an office, and the Diaries contain more than one reference to such waiting and the bitter disappointment when the office was not up to expectation.

These functionaries travelled with a large train of soldiers and servants, but, with the best will in the world, these last could not make the journeys other than tedious and uncomfortable. Still there were alleviations, because of the very taste of which I have spoken. The scenery was often beautiful, and whether the traveller were the Governor himself or his daughter, he noticed and delighted in it. The “Sarashina Diary” is full of this appreciation of nature. We are told of “a very beautiful beach with long-drawn white waves,” of a torrent whose water was “white as if thickened with rice flour.” We need only think of the prints with which we are familiar to be convinced of the accuracy of this picture: “The waves of the outer sea were very high, and we could see them through the pine-trees which grew scattered over the sandy point which stretched between us and the sea. They seemed to strike across the ends of the pine branches and shone like jewels.” The diarist goes on to remark that “it was an interesting sight,” which we can very well believe, since certainly she makes us long to see it.

These journeys were mostly made on horseback, but there were other methods of progression, which, however, were probably not always feasible for long distances. The nobles used various kinds of carriages drawn by one bullock, and there were also palanquins carried by bearers.

It was not only the officials who made journeys, all the world made them to temples and shrines for the good of their souls. There are religious yearnings in all the Diaries, and many Mikados and gentlemen entered the priesthood, Michinaga among them. Sutra recitation and incantation were ceaselessly performed at Court. We can gain some idea of the almost fanatical hold which Buddhism had over the educated mind by the fact that the Fujiwara family built such great temples as Gokurakuji, Hosohoji, Hokoin, Jomyoji, Muryoju-in, etc. It is recorded that Mikado Shirakawa, at a date somewhat subsequent to the Diaries, made pilgrimages four times to Kumano, and during his visits there “worshipped 5470 painted Buddhas, 127 carved Buddhas sixteen feet high, 3150 Buddhas life-sized, 2930 carved Buddhas shorter than three feet, 21 pagodas, 446,630 miniature pagodas.” A busy man truly, but the record does not mention what became of the affairs of state meanwhile. That this worship was by no means lip-devotion merely, any reader of the “Sarashina Diary” can see; that it was mixed with much superstition and a profound belief in dreams is also abundantly evident. But let us, for a moment, recollect the time. It will place the marvel of this old, careful civilization before us as nothing else can.

To be sure, Greece and Rome had been, but they had passed away, or at least their greatness had, gone and apparently left no trace. While these Japanese ladies were writing, Europe was in the full blackness of her darkest ages. Germany was founding the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation,” characteristically founding it with the mailed fist; Moorish civilization was at its height in Spain; Robert Capet was king of poor famine-scourged France; Ethelred the Unready was ruling in England and doing his best to keep off the Danes by payment and massacre. Later, while the “Sarashina Diary” was being written, King Canute was sitting in his armchair and giving orders to the sea. Curious, curious world! So far apart from the one of the Diaries. And to think that even five hundred years later Columbus was sending letters into the interior of Cuba, addressed to the Emperor of Japan!

These Diaries show us a world extraordinarily like our own, if very unlike in more than one important particular. The noblemen and women of Mikado Ichijo’s Court were poets and writers of genius, their taste as a whole has never been surpassed by any people at any time, but their scientific knowledge was elementary in the extreme. Diseases and conflagrations were frequent. In a space of fifty-one years, the Royal Palace burnt down eleven times. During the same period, there were four great pestilences, a terrible drought, and an earthquake. Robbers infested many parts of the country, and were a constant fear to travellers and pilgrims. Childbirth was very dangerous. The picture of the birth of a child to Queen Akiko, with which Murasaki Shikibu’s Diary begins, shows us all its bitter horror. From page to page we share the writer’s suspense, and with our greater knowledge, it is with a sense of wonder that we watch the queen’s return to health.

But, after all, diseases and conflagrations are seldom more than episodes in a normal life lived under sane conditions, and it is just because these Diaries reflect the real life of these three ladies that they are important. The world they portray is in most ways quite as advanced as our own, and in some, much more so. Rice was the staple of food, and although Buddhistic sentiment seldom permitted people to eat the flesh of animals, they had an abundance of fish, which was eaten boiled, baked, raw, and pickled, and a quantity of fruits and nuts. There was no sugar, but cakes were made of fruit and nuts, and there was always rice-wine or saké. Gentlefolk usually dressed in silk. They wore many layers of coloured garments, and delighted in the harmony produced by the colour combinations of silk over silk, or of a bright lining subdued by the tone of an outer robe. The ladies all painted their faces, and the whole toilet was a matter of sufficient moment to raise it into a fine art. Many of these lovely dresses are described by Murasaki Shikibu, for instance: “The beautiful shape of their hair, tied with bands, was like that of the beauties in Chinese pictures. Lady Saémon held the King’s sword. She wore a blue-green patternless karaginu and shaded train with floating bands and belt of ‘floating thread’ brocade dyed in dull red. Her outer robe was trimmed with five folds and was chrysanthemum coloured. The glossy silk was of crimson; her figure and movement, when we caught a glimpse of it, was flower-like and dignified. Lady Ben-no-Naishi held the box of the King’s seals. Her uchigi was grape-coloured. She is a very small and smile-giving person and seemed shy and I was sorry for her…. Her hair bands were blue-green. Her appearance suggested one of the ancient dream-maidens descended from heaven.” A little later she tells us that “the beaten stuffs were like the mingling of dark and light maple leaves in Autumn”; and, describing in some detail the festivity at which these ladies appeared, she makes the comment that “only the right body-guard wore clothes of shrimp pink.” To one in love with colour, these passages leave a very nostalgia for the bright and sophisticated Court where such things could be.

And everywhere, everywhere, there is poetry. A gentleman hands a lady a poem on the end of his fan and she is expected to reply in kind within the instant. Poems form an important part in the ritual of betrothal. A daughter of good family never allowed herself to be seen by men (a custom which appears to have admitted many exceptions). A man would write a poetical love-letter to the lady of his choice which she must answer amiably, even should she have no mind to him. If, however, she were happily inclined, he would visit her secretly at night and leave before daybreak. He would then write again, following which she would give a banquet and introduce him to her family. After this, he could visit her openly, although she would still remain for some time in her father’s house. This custom of love-letter writing and visiting is shown in Izumi Shikibu’s Diary. Obviously the poems were short, and here, in order to understand those in the text, it may be well to consider for a moment in what Japanese poetry consists.

Japanese is a syllabic language like our own, but, unlike our own, it is not accented. Also, every syllable ends with a vowel, the consequence being that there are only five rhymes in the whole language. Since the employment of so restricted a rhyme scheme would be unbearably monotonous, the Japanese hit upon the happy idea of counting syllables. Our metrical verse also counts syllables, but we combine them into different kinds of accented feet. Without accent, this was not possible, so the Japanese poet limits their number and uses them in a pattern of alternating lines. His prosody is based upon the numbers five and seven, a five-syllable line alternating with one of seven syllables, with, in some forms, two seven-syllable lines together at the end of a period, in the manner of our couplet. The favourite form, the “tanka,” is in thirty-one syllables, and runs five, seven, five, seven, seven. There is a longer form, the “naga-uta,” but it has never been held in as high favour. The poems in the Diaries are all tankas in the original. It can be seen that much cannot be said in so confined a medium, but much can be suggested, and it is just in this art of suggestion that the Japanese excel. The “hokku” is an even briefer form. In it, the concluding hemistich of the tanka is left off, and it is just in his hemistich that the meaning of the poem is brought out, so that the hokku is a mere essence, a whiff of an idea to be created in full by the hearer. But the hokku was not invented until the fifteenth century; before that, the tanka, in spite of occasional attempts to vary it by adding more lines, changing their order, using the pattern in combination as a series of stanzas, etc, reigned practically supreme, and it is still the chief classic form for all Japanese poetry.

Having briefly washed in the background of the Diaries, we must notice, for a moment, the three remarkable ladies who are the foreground.

Murasaki Shikibu was the daughter of Fujiwara Tametoki, a scion of a junior branch of the famous family. She was born in 978. Murasaki was not her real name, which was apparently To Shikibu (Shikibu is a title) derived from that of her father. There are two legends about the reason for her receiving the name Murasaki. One is that she was given it in playful allusion to her own heroine in the “Genji Monogatari,” who was called Murasaki. The other legend is more charming. It seems that her mother was one of the nurses of Mikado Ichijo, who was so fond of her that he gave her daughter this name, in reference to a well-known poem:

“When the purple grass (Murasaki) is in full colour,

One can scarcely perceive the other plants in the field.”

From the Murasaki grass, the word has come to mean a colour which includes all the shades of purple, violet, and lavender. In 996, or thereabouts, she accompanied her father to the Province of Echizen, of which he had become governor. A year later, she returned to Kiōto, and, within a twelvemonth, married another Fujiwara, Nobutaka. The marriage seems to have been most happy, to judge from the constant expressions of grief in her Diary for her husband’s death, which occurred in 1001, a year in which Japan suffered from a great pestilence. A daughter was born to them in 1000. From her husband’s death, until 1005, she seems to have lived in the country, but in this year she joined the Court as one of Queen Akiko’s ladies; before that, however (and again I must insist that these early dates are far from determined), she had made herself famous, not only for her own time, but for all time, by writing the first realistic novel of Japan. This book is the “Genji Monogatari” or “Narrative of Genji.”

Hitherto, Japanese authors had confined themselves to stories of no great length, and which relied for their interest on a fairy or wonder element. The “Genji Monogatari” struck out an entirely new direction. It depicted real life in Kiōto as a contemporary gentleman might have lived it. It founded its interest on the fact that people like to read about themselves, but this, which seems to us a commonplace, was a glaring innovation when Murasaki Shikibu attempted it; it was, in fact, the flash from a mind of genius. The book follows the life of Prince Genji from his birth to his death at the age of fifty-one, and the concluding books of the series pursue the career of one of his sons. It is an enormous work, comprising no less than fifty-four books and running to over four thousand pages—the genealogical tree of the personages alone is eighty pages long—but no reader of the Diary will need to be convinced that the “Genji” is not merely sprightly and captivating, but powerful as well. The lady was shrewd, and if she were also kindly and very attractive, nevertheless she saw with an uncompromising eye. Her critical faculty never sleeps, and takes in the minutest detail of anything she sees, noting unerringly every little rightness and wrongness connected with it. She watches the approach of the Mikado, and touches the matter so that we get its exact shade: “When the Royal palanquin drew near, the bearers, though they were rather honourable persons, bent their heads in absolute humility as they ascended the steps. Even in the highest society there are grades of courtesy, but these men were too humble.”

No one with such a gift can fail to be lonely, and Murasaki Shikibu seems very lonely, but it is not the passionate rebellion of Izumi Shikibu, nor the abiding melancholy of the author of the “Sarashina Diary”; rather is it the disillusion of one who has seen much of the world, and knows how little companionship she may expect ever to find: “It is useless to talk with those who do not understand one and troublesome to talk with those who criticize from a feeling of superiority. Especially one-sided persons are troublesome. Few are accomplished in many arts and most cling narrowly to their own opinion.”

I have already shown Murasaki Shikibu’s beautiful taste in dress, but indeed it is in everything. When she says “The garden [on a moonlight night] was admirable,” we know that it must have been of an extraordinary perfection.

The Diary proves her dramatic sense, as the “Genji” would also do could it find so sympathetic a translator. No wonder, then, that it leapt into instant fame. There is a pretty legend of her writing the book at the Temple of Ishiyama at the southern end of Lake Biwa. The tale gains verisimilitude in the eyes of visitors by the fact that they are shown the chamber in the temple in which she wrote and the ink-slab she used, but, alas! it is not true. We do not know where she wrote, nor even exactly when. The “Genji” is supposed to have been begun in 1002, and most commentators believe it to have been finished in 1004. That she should have been called to Court in the following year, seems extremely natural. Queen Akiko must have counted herself most fortunate in having among her ladies so famous a person.

The Diary tells the rest, the Diary which was begun in 1007. We know no more of Murasaki Shikibu except that no shade of scandal ever tinged her name.

One of the strangest and most interesting things about the Diaries is that their authors were such very different kinds of people. Izumi Shikibu is as unlike Murasaki Shikibu as could well happen. As different as the most celebrated poet of her time is likely to be from the most celebrated novelist, for Izumi Shikibu is the greatest woman poet which Japan has had. The author of seven volumes of poems, this Diary is the only prose writing of hers which is known. It is an intimate account of a love affair which seems to have been more than usually passionate and pathetic. Passionate, provocative, enchanting, it is evident that Izumi Shikibu could never have been the discriminating observer, the critic of manners, which Murasaki Shikibu became. Life was powerless to mellow so vivid a personality; but neither could it subdue it. She gives us no suggestion of resignation. She lived intensely, as her Diary shows; she always had done so, and doubtless she always did. We see her as untamable, a genius compelled to follow her inclinations. Difficult to deal with, maybe, like strong wine, but wonderfully stimulating.

Izumi Shikibu was born in 974. She was the eldest daughter of Ōe Masamune, another Governor of Echizen. In 995, she married Tachibana Michisada, Governor of Izumi, hence her name. From this gentleman she was divorced, but just when we do not know, and he died shortly after, probably during the great pestilence which played such havoc throughout Japan and in which Murasaki Shikibu’s husband had also died. Her daughter, who followed in her mother’s footsteps as a poet, had been born in 997. But Izumi Shikibu was too fascinating and too petulant to nurse her disappointment in a chaste seclusion. She became the mistress of Prince Tametaka, who also died in 1002. It is very soon after this event that the Diary begins. Her new lover was Prince Atsumichi, and the Diary seems to have been written solely to appease her mind, and to record the poems which passed between them and which Izumi Shikibu evidently regarded as the very essence of their souls.

In the beginning, the affair was carried on with the utmost secrecy, but clandestine meetings could not satisfy the lovers, and at last the Prince persuaded her to take up her residence in the South Palace as one of his ladies. Considering the manners of the time, it is a little puzzling to see why there should have been such an outcry at this, but outcry there certainly was. The Princess took violent umbrage at the Prince’s proceeding and left the Palace on a long visit to her relations. So violent grew the protestations in the little world of the Court that, in 1004, Izumi Shikibu left the Palace and separated herself entirely from the Prince. It was probably to emphasize the definiteness of the separation that, immediately after her departure, she married Fujiwara Yasumasa, Governor of Tango, and left with him for that Province in 1005. The facts bear out this supposition, but we do not know it from her own lips, as the Diary breaks off soon after she reaches the South Palace.

In 1008, she was summoned back to Kiōto to serve the Queen in the same Court where Murasaki Shikibu had been since 1005. Whatever effect the scandal may have had four years earlier, her receiving the post of lady-in-waiting proves it to have been worth forgetting in view of her fame, and Queen Akiko must have rejoiced to add this celebrated poet to her already remarkable bevy of ladies. Of course there was jealousy—who can doubt it? No reader of the Diaries can imagine that Izumi Shikibu and Murasaki Shikibu can have been sympathetic, and we must take with a grain of salt the latter’s caustic comment: “Lady Izumi Shikibu corresponds charmingly, but her behavior is improper indeed. She writes with grace and ease and a flashing wit. There is a fragrance even in her smallest words. Her poems are attractive, but they are only improvisations which drop from her mouth spontaneously. Every one of them has some interesting point, and she is acquainted with ancient literature also, but she is not like a true artist who is filled with the genuine spirit of poetry. Yet I think even she cannot presume to pass judgment on the poems of others.” Is it possible that Izumi Shikibu had been so rash as to pass judgment on some of Murasaki Shikibu’s efforts?

Of course it is beyond the power of any translation to preserve the full effect of the original, but even in translation, Izumi Shikibu’s poems are singularly beautiful and appealing. In her own country, they are considered never to have been excelled in freshness and freedom of expression. There is something infinitely sad in this, which she is said to have written on her death-bed, as the end of a passionate life:

“Out of the dark,

Into a dark path

I now must enter:

Shine [on me] from afar

Moon of the mountain fringe.”[1]

In Japanese poetry, Amita-Buddha is often compared to the moon which rises over the mountains and lights the traveller’s path.

Very different again is the lady who wrote the “Sarashina Diary,” and it is a very different kind of record. Murasaki Shikibu’s Diary is concerned with a few years of her life, Izumi Shikibu’s with one episode only of hers, but the “Sarashina Diary” covers a long period in the life of its author. The first part was written when she was twelve years old, the last entry was made when she was past fifty. It begins with a journey from Shimōsa to Kiōto by the Tōkaidō in 1021, which is followed by a second journey some years later from Kiōto to Sarashina, a place which has never been satisfactorily identified, although some critics have supposed it to have been in the Province of Shinano. The rest of the Diary consists of jottings at various times, accounts of books read, of places seen, of pilgrimages to temples, of records of dreams and portents, of communings with herself on life and death, of expressions of resignation and sorrow.

The book takes its name from the second of the journeys, “Sarashina Nikki,” meaning simply “Sarashina Diary,” for, strangely enough, we do not know the author’s name. We do know, however, that she was the daughter of Fujiwara Takasué, and that she was born in 1009. In 1017, Takasué was appointed governor of a province, and went with his daughter to his new post. It is the return journey, made in 1021, with which the Diary opens.

Takasué’s daughter shared with so many of her contemporaries the deep love of nature and the power to express this love in words. I have already quoted one or two of her entries on this journey. We follow the little company over mountains and across rivers, we camp with them by night, and tremble as they trembled lest robbers should attack them. We see what the little girl saw: “The mountain range called Nishitomi is like folding screens with good pictures,” “people say that purple grass grows in the fields of Mushashi, but it is only a waste of various kinds of reeds, which grow so high that we cannot see the bows of our horsemen who are forcing their way through the tall grass,” and share her disappointment when she says: “We passed a place called ‘Eight Bridges,’ but it was only a name, no bridge and no pretty sight.”

They reach Kiōto and a rather dull life begins, enlivened only by the avid reading of romances, among them the “Genji Monogatari.” Then her sister dies giving birth to a child, and the life becomes, not only dull, but sorrowful. After a time, the lady obtains a position at Court, but neither her bringing up nor her disposition had suited her for such a place. She mentions that “Mother was a person of extremely antiquated mind,” and it is evident that she had been taught to look inward rather than outward. An abortive little love affair lightens her dreariness for a moment. Life had dealt hardly with the sensitive girl, from year to year she grows more wistful, but suddenly something happens, a mere hint of a gleam, but opening a possibility of brightness. Who he was, we do not know, but she met him on an evening when “there was no starlight, and a gentle shower fell in the darkness.” They talked and exchanged poems, but she did not meet him again until the next year; then, after an evening entertainment to which she had not gone, “when I looked out, opening the sliding door on the corridor, I saw the morning moon very faint and beautiful,” and he was there. Again they exchanged poems and she believed that happiness had at last arrived. He was to come with his lute and sing to her. “I wanted to hear it,” she writes, “and waited for the fit occasion, but there was none, ever.” A year later she has lost hope, she writes a poem and adds, “So I composed that poem—and there is nothing more to tell.” Nothing more, indeed, but what is told conveys all the misery of her deceived longing.

The last part of the Diary is concerned chiefly with accounts of pilgrimages and dreams. She married, who and when is not recorded, and bore children. Her husband dies, and with his death the spring of her life seems to have run down. Her last entry is very sad: “My people went to live elsewhere and I lived alone in my solitary home.” So we leave her, “a beautiful, shy spirit whose life had known much sorrow.”

[1] Translation by Arthur Waley in Japanese Poetry.

DIARIES OF COURT LADIES OF OLD JAPAN

I

THE SARASHINA DIARY

A.D. 1009-1059

I was brought up in a distant province[1] which lies farther than the farthest end of the Eastern Road. I am ashamed to think that inhabitants of the Royal City will think me an uncultured girl.

Somehow I came to know that there are such things as romances in the world and wished to read them. When there was nothing to do by day or at night, one tale or another was told me by my elder sister or stepmother, and I heard several chapters about the shining Prince Genji.[2] My longing for such stories increased, but how could they recite them all from memory? I became very restless and got an image of Yakushi Buddha[3] made as large as myself. When I was alone I washed my hands and went secretly before the altar and prayed to him with all my life, bowing my head down to the floor. “Please let me go to the Royal City. There I can find many tales. Let me read all of them.”

When thirteen years old, I was taken to the Royal City. On the third of the Long-moon month,[4] I removed [from my house] to Imataté, the old house where I had played as a child being broken up. At sunset in the foggy twilight, just as I was getting into the palanquin, I thought of the Buddha before which I had gone secretly to pray—I was sorry and secretly shed tears to leave him behind.

Outside of my new house [a rude temporary, thatched one] there is no fence nor even shutters, but we have hung curtains and sudaré.[5] From that house, standing on a low bluff, a wide plain extends towards the South. On the East and West the sea creeps close, so it is an interesting place. When fogs are falling it is so charming that I rise early every morning to see them. Sorry to leave this place.

On the fifteenth, in heavy dark rain, we crossed the boundary of the Province and lodged at Ikada in the Province of Shimofusa. Our lodging is almost submerged. I am so afraid I cannot sleep. I see only three lone trees standing on a little hill in the waste.

The next day was passed in drying our dripping clothes and waiting for the others to come up.[6]

On the seventeenth, started early in the morning, and crossed a deep river. I heard that in this Province there lived in olden times a chieftain of Mano. He had thousand and ten thousand webs of cloth woven and dipped them [for bleaching] in the river which now flows over the place where his great house stood. Four of the large gate-posts remained standing in the river.

Hearing the people composing poems about this place, I in my mind:

Had I not seen erect in the river

These solid timbers of the olden time

How could I know, how could I feel

The story of that house?

That evening we lodged at the beach of Kurodo. The white sand stretched far and wide. The pine-wood was dark—the moon was bright, and the soft blowing of the wind made me lonely. People were pleased and composed poems. My poem:

For this night only

The autumn moon at Kurodo beach shall shine for me,

For this night only!—I cannot sleep.

Early in the morning we left this place and came to the Futoi River[7] on the boundary between Shimofusa and Musashi. We lodged at the ferry of Matsusato[8] near Kagami’s rapids,[9] and all night long our luggage was being carried over.

My nurse had lost her husband and gave birth to her child at the boundary of the Province, so we had to go up to the Royal City separately. I was longing for my nurse and wanted to go to see her, and was brought there by my elder brother in his arms. We, though in a temporary lodging, covered ourselves with warm cotton batting, but my nurse, as there was no man to take care of her, was lying in a wild place [and] covered only with coarse matting. She was in her red dress.

The moon came in, lighting up everything, and in the moonlight she looked transparent. I thought her very white and pure. She wept and caressed me, and I was loath to leave her. Even when I went with lingering heart, her image remained with me, and there was no interest in the changing scenes.

The next morning we crossed the river in a ferry-boat in our palanquins. The persons who had come with us thus far in their own conveyances went back from this place. We, who were going up to the Royal City, stayed here for a while to follow them with our eyes; and as it was a parting for life all wept. Even my childish heart felt sorrow.

Now it is the Province of Musashi. There is no charm in this place. The sand of the beaches is not white, but like mud. People say that purple grass[10] grows in the fields of Musashi, but it is only a waste of various kinds of reeds, which grow so high that we cannot see the bows of our horsemen who are forcing their way through the tall grass. Going through these reeds I saw a ruined temple called Takeshíba-dera. There were also the foundation-stones of a house with corridor.

“What place is it?” I asked; and they answered:

“Once upon a time there lived a reckless adventurer at Takeshiba.[11] He was offered to the King’s palace [by the Governor] as a guard to keep the watch-fire. He was once sweeping the garden in front of a Princess’s room and singing:

Ah, me! Ah, me! My weary doom to labour here in the Palace!

Seven good wine-jars have I—and three in my province.

There where they stand I have hung straight-stemmed gourds of

the finest—

They turn to the West when the East wind blows,

They turn to the East when the West wind blows,

They turn to the North when the South wind blows,

They turn to the South when the North wind blows.

And there I sit watching them turning and turning forever—

Oh, my gourds! Oh, my wine-jars!

“He was singing thus alone, but just then a Princess, the King’s favourite daughter, was sitting alone behind the misu.[12] She came forward, and, leaning against the door-post, listened to the man singing. She was very interested to think how gourds were above the wine-jars and how they were turning and wanted to see them. She became very zealous for the gourds, and pushing up the blind called the guard, saying, ‘Man, come here!’ The man heard it very respectfully, and with great reverence drew near the balustrade. ‘Let me hear once more what you have been saying.’ And he sang again about his wine-jars. ‘I must go and see them, I have my own reason for saying so,’ said the Princess.

“He felt great awe, but he made up his mind, and went down towards the Eastern Province. He feared that men would pursue them, and that night, placing the Princess on the Seta Bridge,[13] broke a part of it away, and bounding over with the Princess on his back arrived at his native place after seven days’ and seven nights’ journey.

“The King and Queen were greatly surprised when they found the Princess was lost, and began to search for her. Some one said that a King’s guard from the Province of Musashi, carrying something of exquisite fragrance[14] on his back, had been seen fleeing towards the East. So they sought for that guard, and he was not to be found. They said, ‘Doubtless this man went back home.’ The Royal Government sent messengers to pursue them, but when they got to the Seta Bridge they found it broken, and they could not go farther. In the Third month, however, the messengers arrived at Musashi Province and sought for the man. The Princess gave audience to the messengers and said:

“‘I, for some reason, yearned for this man’s home and bade him carry me here; so he has carried me. If this man were punished and killed, what should I do? This is a very good place to live in. It must have been settled before I was born that I should leave my trace [i.e. descendants] in this Province—go back and tell the King so.’ So the messenger could not refuse her, and went back to tell the King about it.

“The King said: ‘It is hopeless. Though I punish the man I cannot bring back the Princess; nor is it meet to bring them back to the Royal City. As long as that man of Takeshiba lives I cannot give Musashi Province to him, but I will entrust it to the Princess.’

“In this way it happened that a palace was built there in the same style as the Royal Palace and the Princess was placed there. When she died they made it into a temple called Takeshíba-dera.[15] The descendants of the Princess received the family name of Musashi. After that the guards of the watch-fire were women.”[16]

We went through a waste of reeds of various kinds, forcing our way through the tall grass. There is the river Asuda along the border of Musashi and Sagami, where at the ferry Arihara Narihira had composed his famous poem.[17] In the book of his poetical works the river is called the river Sumida.

We crossed it in a boat, and it is the Province of Sagami. The mountain range called Nishitomi is like folding screens with good pictures. On the left hand we saw a very beautiful beach with long-drawn curves of white waves. There was a place there called Morokoshi-ga-Hara[18] [Chinese Field] where sands are wonderfully white. Two or three days we journeyed along that shore. A man said:, “In Summer pale and deep Japanese pinks bloom there and make the field like brocade. As it is Autumn now we cannot see them.” But I saw some pinks scattered about blooming pitiably. They said: “It is funny that Japanese pinks are blooming in the Chinese field.”

There is a mountain called Ashigara [Hakoné] which extends for ten and more miles and is covered with thick woods even to its base. We could have only an occasional glimpse of the sky. We lodged in a hut at the foot of the mountain. It was a dark moonless night. I felt myself swallowed up and lost in the darkness, when three singers came from somewhere. One was about fifty years old, the second twenty, and the third about fourteen or fifteen. We set them down in front of our lodging and a karakasa [large paper umbrella] was spread for them. My servant lighted a fire so that we saw them. They said that they were the descendants of a famous singer called Kobata. They had very long hair which hung over their foreheads; their faces were white and clean, and they seemed rather like maids serving in noblemen’s families. They had clear, sweet voices, and their beautiful singing seemed to reach the heavens. All were charmed, and taking great interest made them come nearer. Some one said, “The singers of the Western Provinces are inferior to them,” and at this the singers closed their song with the words, “if we are compared with those of Naniwa” [Osaka].[19] They were pretty and neatly dressed, with voices of rare beauty, and they were wandering away into this fearful mountain. Even tears came to those eyes which followed them as far as they could be seen; and my childish heart was unwilling to leave this rude shelter frequented by these singers.

Next morning we crossed over the mountain.[20] Words cannot express my fear[21] in the midst of it. Clouds rolled beneath our feet. Halfway over there was an open space with a few trees. Here we saw a few leaves of aoi[22] [Asarum caulescens]. People praised it and thought strange that in this mountain, so far from the human world, was growing such a sacred plant. We met with three rivers in the mountain and crossed them with difficulty. That day we stopped at Sekiyama. Now we are in Suruga Province. We passed a place called Iwatsubo [rock-urn] by the barrier of Yokobashiri. There was an indescribably large square rock through a hole in which very cold water came rushing out.

Mount Fuji is in this Province. In the Province where I was brought up [from which she begins this journey] I saw that mountain far towards the West. It towers up painted with deep blue, and covered with eternal snow. It seems that it wears a dress of deep violet and a white veil over its shoulders. From the little level place of the top smoke was going up. In the evening we even saw burning fires there.[23] The Fuji River comes tumbling down from that mountain. A man of the Province came up to us and told us a story.

“Once I went on an errand. It was a very hot day, and I was resting on the bank of the stream when I saw something yellow come floating down. It came to the bank of the river and stuck there. I picked it up and found it to be a scrap of yellow paper with words elegantly written on it in cinnabar. Wondering much I read it. On the paper was a prophecy of the Governors [of provinces] to be appointed next year. As to this Province there were written the names of two Governors. I wondered more and more, and drying the paper, kept it. When the day of the announcement came, this paper held no mistake, and the man who became the Governor of this Province died after three months, and the other succeeded him.”

There are such things. I think that the gods assemble there on that mountain to settle the affairs of each new year.

At Kiyomigaseki, where we saw the sea on the left, there were many houses for the keepers of the barriers. Some of the palisades went even into the sea.

At Tagonoura waves were high. From there we went along by boat. We went with ease over Numajiri and came to the river Ōi. Such a torrent I have never seen. Water, white as if thickened with rice flour, ran fast.

I became ill, and now it is the Province of Totomi. I had almost lost consciousness when I crossed the mountain pass of Sayo-no-Nakayama [the middle mountain of the little night]. I was quite exhausted, so when we came to the bank of the Tenryu River, we had a temporary dwelling built, and passed several days there, and I got better. As the winter was already advanced, the wind from the river blew hard and it became intolerable. After crossing the river we went towards the bridge at Hamana.

When we had gone down towards the East [four years before when her father had been appointed Governor] there had been a log bridge, but this time we could not find even a trace of it, so we had to cross in a boat. The bridge had been laid across an inland bay. The waves of the outer sea were very high, and we could see them through the thick pine-trees which grew scattered over the sandy point which stretched between us and the sea. They seemed to strike across the ends of the pine branches and shone like jewels. It was an interesting sight.

We went forward and crossed over Inohana—an unspeakably weary ascent it was—and then came to Takashi shore of the Province of Mikawa. We passed a place called “Eight-Bridges,” but it was only a name, no bridge and no pretty sight.

In the mountain of Futamura we made our camp under a big persimmon tree. The fruit fell down during the night over our camps and people picked it up.

We passed Mount Miyaji, where we saw red leaves still, although it was the first day of the Tenth month.

Furious mountain winds in their passing

must spare this spot

For red maple leaves are clinging

even yet to the branch.

There was a fort of “If-I-can” between Mikawa and Owari. It is amusing to think how difficult the crossing was, indeed. We passed the Narumi [sounding-sea] shore in the Province of Owari. The evening tides were coming in, and we thought if they came higher we could not cross. So in a panic we ran as fast as we could.

At the border of Mino we crossed a ferry called Kuromata, and arrived at Nogami. There singers came again and they sang all night. Lovingly we thought of the singers of Ashigara.

Snow came, and in the storm we passed the barrier at Fuha, and over the Mount Atsumi, having no heart to look at beautiful sights. In the Province of Omi we stayed four or five days in a house at Okinaga. At the foot of Mitsusaka Mountain light rain fell night and day mixed with hail. It was so melancholy that we left there and passed by Inugami, Kanzaki, and Yasu without receiving any impressions. The lake stretched far and wide, and we caught occasional glimpses of Nadeshima and Chikubushima [islands]. It was a very pretty sight. We had great difficulty at the bridge of Seta, for it had fallen in. We stopped at Awazu, and arrived at the Royal City after dark on the second day of the Finishing month.

When we were near the barrier I saw the face of a roughly hewn Buddha sixteen feet high which towered over a rude fence. Serene and indifferent to its surroundings it stood unregarded in this deserted place; but I, passing by, received a message from it. Among so many provinces [through which I have passed] the barriers at Kiyomigata and Osaka were far better than the others.

It was dark when I arrived at the residence on the west of the Princess of Sanjo’s mansion.[24] Our garden was very wide and wild with great, fearful trees not inferior to those mountains I had come from. I could not feel at home, or keep a settled mind. Even then I teased mother into giving me books of stories, after which I had been yearning for so many years. Mother sent a messenger with a letter to Emon-no-Myōgu, one of our relatives who served the Princess of Sanjo. She took interest in my strange passion and willingly sent me some excellent manuscripts in the lid of a writing-box,[25] saying that these copies had been given her by the Princess. My joy knew no bounds and I read them day and night; I soon began to wish for more, but as I was an utter stranger to the Royal City, who would get them for me?

My stepmother [meaning one of her father’s wives] had once been a lady-in-waiting at the court, and she seemed to have been disappointed in something. She had been regretting the World [her marriage], and now she was to leave our home. She beckoned her own child, who was five years old, and said, “The time will never come when I shall forget you, dear heart”; and pointing to a huge plum-tree which grew close to the eaves, said, “When it is in flower I shall come back”; and she went away. I felt love and pity for her, and while I was secretly weeping, the year, too, went away.

“IT WAS ALL IN FLOWER AND YET NO TIDINGS FROM HER”

“When the plum-tree blooms I shall come back”—I pondered over these words and wondered whether it would be so. I waited and waited with my eye hung to the tree. It was all in flower[26] and yet no tidings from her. I became very anxious [and at last] broke a branch and sent it to her [of course with a poem]:

You gave me words of hope, are they not long delayed?

The plum-tree is remembered by the Spring,

Though it seemed dead with frost.

She wrote back affectionate words with a poem:

Wait on, never forsake your hope,

For when the plum-tree is in flower

Even the unpromised, the unexpected, will come to you.

During the spring [of 1022] the world was disquieted.[27] My nurse, who had filled my heart with pity on that moonlight night at the ford of Matsuzato, died on the moon-birthday of the Ever-growing month [first day of March], I lamented hopelessly without any way to set my mind at ease, and even forgot my passion for romances.

I passed day after day weeping bitterly, and when I first looked out of doors[28] [again] I saw the evening sun on cherry-blossoms all falling in confusion [this would mean four weeks later].

Flowers are falling, yet I may see them again

when Spring returns.

But, oh, my longing for the dear person

who has departed from us forever!

I also heard that the daughter of the First Adviser[29] to the King was lost [dead]. I could sympathize deeply with the sorrow of her lord, the Lieutenant-General, for I still felt my own sorrow.

When I had first arrived at the Capital I had been given a book of the handwriting of this noble lady for my copy-book. In it were written several poems, among them the following:

When you see the smoke floating up the valley of

Toribe Hill,[30]

Then you will understand me, who seemed as shadow-like

even while living.

I looked at these poems which were written in such a beautiful handwriting, and I shed more tears. I sat brooding until mother troubled herself to console me. She searched for romances and gave them to me, and I became consoled unconsciously. I read a few volumes of Genji-monogatari and longed for the rest, but as I was still a stranger here I had no way of finding them. I was all impatience and yearning, and in my mind was always praying that I might read all the books of Genji-monogatari from the very first one.

While my parents were shutting themselves up in Udzu-Masa[31] Temple, I asked them for nothing except this romance, wishing to read it as soon as I could get it, but all in vain. I was inconsolable. One day I visited my aunt, who had recently come up from the country. She showed a tender interest in me and lovingly said I had grown up beautifully. On my return she said: “What shall I give you? You will not be interested in serious things: I will give you what you like best.” And she gave me more than fifty volumes of Genji-monogatari put in a case, as well as Isé-monogatari, Yojimi, Serikawa, Shirara, and Asa-udzu.[32] How happy I was when I came home carrying these books in a bag! Until then I had only read a volume here and there, and was dissatisfied because I could not understand the story.

Now I could be absorbed in these stories, taking them out one by one, shutting myself in behind the kichō.[33] To be a Queen were nothing compared to this!

All day and all night, as late as I could keep my eyes open, I did nothing but look at the books, setting a lamp[34] close beside me.

Soon I learnt by heart all the names in the books, and I thought that a great thing.

Once I dreamt of a holy priest in yellow Buddhist scarf who came to me and said, “Learn the fifth book of the Hokekkyo[35] at once.”

I did not tell any one about this, nor had I any mind to learn it, but continued to bathe in the romances. Although I was still ugly and undeveloped [I thought to myself] the time would come when I should be beautiful beyond compare, with long, long hair. I should be like the Lady Yugao [in the romance] loved by the Shining Prince Genji, or like the Lady Ukifuné, the wife of the General of Uji [a famous beauty]. I indulged in such fancies—shallow-minded I was, indeed!

Could such a man as the Shining Prince be living in this world? How could General Kaoru [literal translation, “Fragrance”] find such a beauty as Lady Ukifuné to conceal in his secret villa at Uji? Oh! I was like a crazy girl.

While I had lived in the country, I had gone to the temple from time to time, but even then I could never pray like others, with a pure heart. In those days people learned to recite sutras and practise austerities of religious observance after the age of seventeen or eighteen, but I could scarcely even think of such matters. The only thing that I could think of was the Shining Prince who would some day come to me, as noble and beautiful as in the romance. If he came only once a year I, being hidden in a mountain villa like Lady Ukifuné, would be content. I could live as heart-dwindlingly as that lady, looking at flowers, or moonlit snowy landscape, occasionally receiving long-expected lovely letters from my Lord! I cherished such fancies and imagined that they might be realized.

On the moon-birth of the Rice-Sprout month I saw the white petals of the Tachibana tree [a kind of orange] near the house covering the ground.

Scarce had my mind received with wonder;

The thought of newly fallen snow—

Seeing the ground lie white—

When the scent of Tachibana flowers

Arose from fallen blossoms.

In our garden trees grew as thick as in the dark forest of Ashigara, and in the Gods-absent month[36] its red leaves were more beautiful than those of the surrounding mountains. A visitor said, “On my way thither I passed a place where red leaves were beautiful”; and I improvised:

No sight can be more autumnal

than that of my garden

Tenanted by an autumnal person

weary of the world!

I still dwelt in the romances from morning to night, and as long as I was awake.

I had another dream: a man said that he was to make a brook in the garden of the Hexagon Tower to entertain the Empress of the First Rank of Honour. I asked the reason, and the man said, “Pray to the Heaven-illuminating honoured Goddess.” I did not tell any one about this dream or even think of it again. How shallow I was!

In the Spring I enjoyed the Princess’s garden. Cherry-blossoms waited for!—cherry-blossoms lamented over! In Spring I love the flowers whether in her garden or in mine.

On the moon-hidden day of the Ever-growing month [March 30, 1023], I started for a certain person’s house to avoid the evil influence of the earth god.[37] There I saw delightful cherry-blossoms still on the tree and the day after my return I sent this poem:

Alone, without tiring, I gazed at the cherry-blossoms of your garden.

The Spring was closing—they were about to fall—

Always when the flowers came and went, I could think of nothing but those days when my nurse died, and sadness descended upon me, which grew deeper when I studied the handwriting of the Honoured Daughter of the First Adviser.

Once in the Rice-Sprout month, when I was up late reading a romance, I heard a cat mewing with a long-drawn-out cry. I turned, wondering, and saw a very lovely cat. “Whence does it come?” I asked. “Sh,” said my sister, “do not tell anybody. It is a darling cat and we will keep it.”

The cat was very sociable and lay beside us. Some one might be looking for her [we thought], so we kept her secretly. She kept herself aloof from the vulgar servants, always sitting quietly before us. She turned her face away from unclean food, never eating it. She was tenderly cared for and caressed by us.

Once sister was ill, and the family was rather upset. The cat was kept in a room facing the north [i.e. a servant’s room], and never was called. She cried loudly and scoldingly, yet I thought it better to keep her away and did so. Sister, suddenly awakening, said to me, “Where is the cat kept? Bring her here.” I asked why, and sister said: “In my dream the cat came to my side and said, ‘I am the altered form of the late Honoured Daughter of the First Adviser to the King. There was a slight cause [for this]. Your sister has been thinking of me affectionately, so I am here for a while, but now I am among the servants. O how dreary I am!’ So saying she wept bitterly. She appeared to be a noble and beautiful person and then I awoke to hear the cat crying! How pitiful!”

The story moved me deeply and after this I never sent the cat away to the north-facing room, but waited on her lovingly. Once, when I was sitting alone, she came and sat before me, and, stroking her head, I addressed her: “You are the first daughter of the Noble Adviser? I wish to let your father know of it.” The cat watched my face and mewed, lengthening her voice.

It may be my fancy, but as I was watching her she seemed no common cat. She seemed to understand my words, and I pity her.

I had heard that a certain person possessed the Chogonka[38] [Song of the Long Regret] retold from the original of the Chinese poet Li T’ai Po. I longed to borrow it, but was too shy to say so.

On the seventh day of the Seventh month I found a happy means to send my word [the suggestion of my wish]:

This is the night when in the ancient Past,

The Herder Star embarked to meet the Weaving One;

In its sweet remembrance the wave rises high in the River of Heaven.[39]

Even so swells my heart to see the famous book.

The answer was:

The star gods meet on the shore of the Heavenly River,

Like theirs full of ecstasy is my heart

And grave things of daily life are forgotten

On the night your message comes to me.

On the thirteenth day of that month the moon shone very brightly. Darkness was chased away even from every corner of the heavens. It was about midnight and all were asleep.

We were sitting on the veranda. My sister, who was gazing at the sky thoughtfully, said, “If I flew away now, leaving no trace behind, what would you think of it?” She saw that her words shocked me, and she turned the conversation [lightly] to other things, and we laughed.

Then I heard a carriage with a runner before it stop near the house. The man in the carriage called out, “Ogi-no-ha! Ogi-no-ha!” [Reed-leaf, a woman’s name or pet name] twice, but no woman made reply. The man cried in vain until he was tired of it, and played his flute [a reed-pipe] more and more searchingly in a very beautiful rippling melody, and [at last] drove away.

Flute music in the night,

“Autumn Wind”[40] sighing,

Why does the reed-leaf make no reply?

Thus I challenged my sister, and she took it up:

Alas! light of heart

Who could so soon give over playing!

The wind did not wait

For the response of the reed-leaf.

We sat together looking up into the firmament, and went to bed after daybreak.

At midnight of the Deutzia month [April, 1024] a fire broke out, and the cat which had been waited on as a daughter of the First Adviser was burned to death. She had been used to come mewing whenever I called her by the name of that lady, as if she had understood me. My father said that he would tell the matter to the First Adviser, for it is a strange and heartfelt story. I was very, very sorry for her.

Our new temporary shelter was far narrower than the other. I was sad, for we had a very small garden and no trees. I thought with regret of the old spacious garden which was wild as a deep wood, and in time of flowers and red leaves the sight of it was never inferior to the surrounding mountains.

In the garden of the opposite house white and red plum-blossoms grew in confusion and their perfume came on the wind and filled me with thoughts of our old home.

When from the neighbouring garden the perfume-laden air

Saturates my soul with memories,

Rises the thought of the beloved plum-tree

Blooming under the eaves of the house which is gone.

On the moon-birth of the Rice-Sprout month my sister died after giving birth to a child. From childhood, even a stranger’s death had touched my heart deeply. This time I lamented, filled with speechless pity and sorrow.

While mother and the others were with the dead, I lay with the memory-awakening children one on either side of me. The moonlight found its way through the cracks of the roof [perhaps of their temporary dwelling] and illumined the face of the baby. The sight gave my heart so deep a pang that I covered its face with my sleeve, and drew the other child closer to my side, mothering the unfortunate.

After some days one of my relatives sent me a romance entitled “The Prince Yearning after the Buried,” with the following note: “The late lady had asked me to find her this romance. At that time I thought it impossible, but now to add to my sorrow, some one has just sent it to me.”

I answered:

What reason can there be that she

Strangely should seek a romance of the buried?

Buried now is the seeker

Deep under the mosses.

My sister’s nurse said that since she had lost her, she had no reason to stay and went back to her own home weeping.

Thus death or parting separates us each from the other,

Why must we part? Oh, world too sad for me!

“For remembrance of her I wanted to write about her,” began a letter from her nurse—but it stopped short with the words, “Ink seems to have frozen up, I cannot write any more.”[41]

How shall I gather memories of my sister?

The stream of letters is congealed.

No comfort may be found in icicles.

So I wrote, and the answer was:

Like the comfortless plover of the beach

In the sand printing characters soon to be washed away,

Unable to leave a more enduring trace in this fleeting world.

That nurse went to see the grave and returned sobbing, saying:

I seek her in the field, but she is not there,

Nor is she in the smoke of the cremation.

Where is her last dwelling-place?

How can I find it?

The lady who had been my stepmother heard of this [and wrote]:

When we wander in search of her,

Ignorant of her last dwelling-place,

Standing before the thought

Tears must be our guide.

The person who had sent “The Prince Yearning after the Buried” wrote:

How she must have wandered seeking the unfindable

In the unfamiliar fields of bamboo grasses,

Vainly weeping!

Reading these poems my brother, who had followed the funeral that night, composed a poem:

Before my vision

The fire and smoke of burning

Arose and died again.

To bamboo fields there is no more returning,

Why seek there in vain?

It snowed for many days, and I thought of the nun who lived on Mount Yoshino, to whom I wrote:

Snow has fallen

And you cannot have

Even the unusual sight of men

Along the precipitous path of the Peak of Yoshino.

On the Sociable month of the next year father was looking forward with happy expectation to the night when he might expect an appointment as Governor of a Province. He was disappointed, and a person who might have shared our joy wrote to me, saying:

“I anxiously waited for the dawn with uncertain hope.”

The temple bell roused me from dreams

And waiting for the starlit dawn

The night, alas! was long as are

One hundred autumn nights.

I wrote back:

Long was the night.

The bell called from dreams in vain,

For it did not toll our realized hopes.

Towards the moon-hidden days [last days] of the Rice-Sprout month I went for a certain reason to a temple at Higashiyama.[42] On the way the nursery beds for rice-plants were filled with water, and the fields were green all over with the young growing rice. It was a smile-presenting sight. It gave a feeling of loneliness to see the dark shadow of the mountain close before me. In the lovely evenings water-rails chattered in the fields.

The water-rails cackle as if they were knocking at the gate,

But who would be deceived into opening the door, saying,

Our friend has come along the mountain path in the dark night?

As the place was near the Reizan Temple I went there to worship. Arriving so far I was fatigued, and drank from a stone-lined well beside the mountain temple, scooping the water into the hollow of my hand. My friend said, “I could never have enough of this water.” “Is it the first time,” I asked, “that you have tasted the satisfying sweetness of a mountain well drunk from the hollow of your hand?” She said, “It is sweeter than to drink from a shallow spring, which becomes muddy even from the drops which fall from the hand which has scooped it up.”[43] We came home from the temple in the full brightness of evening sunshine, and had a clear view of Kioto below us.

My friend, who had said that a spring becomes muddy even with drops falling into it, had to go back to the Capital.

I was sorry to part with her and sent word the next morning:

When the evening sun descends behind the mountain peak,

Will you forget that it is I who gaze with longing

Towards the place where you are?

The holy voices of the priests reciting sutras in their morning service could be heard from my house and I opened the door. It was dim early dawn; mist veiled the green forest, which was thicker and darker than in the time of flowers or red leaves. The sky seemed clouded this lovely morning. Cuckoos were singing on the near-by trees.

O for a friend—that we might see and listen together!

O the beautiful dawn in the mountain village!—

The repeated sound of cuckoos near and far away.

On that moon-hidden day cuckoos sung clamorously on trees towards the glen. “In the Royal City poets may be awaiting you, cuckoos, yet you sing here carelessly from morning till night!”

One who sat near me said: “Do you think that there is one person, at least, in the Capital who is listening to cuckoos, and thinking of us at this moment?”—and then:

Many in the Royal City like to gaze on the calm moon.

But is there one who thinks of the deep mountain

Or is reminded of us hidden here?

I replied:

In the dead of night, moon-gazing,

The thought of the deep mountain affrighted,

Yet longings for the mountain village

At all other moments filled my heart.

Once, towards dawn, I heard footsteps which seemed to be those of many persons coming down the mountain. I wondered and looked out. It was a herd of deer which came close to our dwelling. They cried out. It was not pleasant to hear them near by.

It is sweet to hear the love-call of a deer to its mate,

In Autumn nights, upon the distant hills.

I heard that an acquaintance had come near my residence and gone back without calling on me. So I wrote:

Even this wandering wind among the pines of the mountain—

I’ve heard that it departs with murmuring sound.

[That is, you are not like it. You do not speak when going away.]

In the Leaf-Falling month [September] I saw the moon more than twenty days old. It was towards dawn; the mountain-side was gloomy and the sound of the waterfall was all [I heard]. I wish that lovers [of nature] may see the after-dawn-waning moon in a mountain village at the close of an autumn night.

I went back to Kioto when the rice-fields, which had been filled with water when I came, were dried up, the rice being harvested. The young plants in their bed of water—the plants harvested—the fields dried up—so long I remained away from home.

‘T was the moon-hidden of the Gods-absent month when I went there again for temporary residence. The thick grown leaves which had cast a dark shade were all fallen. The sight was heartfelt over all. The sweet, murmuring rivulet was buried under fallen leaves and I could see only the course of it.

Even water could not live on—

So lonesome is the mountain

Of the leaf-scattering stormy wind.

[At about this time the author of this diary seems to have had some family troubles. Her father received no appointment from the King—they were probably poor, and her gentle, poetic nature did not incline her to seek useful friends at court; therefore many of the best years of her youth were spent in obscurity—a great contrast to the “Shining-Prince” dreams of her childhood.]

I went back to Kioto saying that I should come again the next Spring, could I live so long, and begged the nun to send word when the flowering-time had come.

It was past the nineteenth of the Ever-growing month of the next year [1026], but there were no tidings from her, so I wrote:

No word about the blooming cherry-blossoms,

Has not the Spring come for you yet?

Or does the perfume of flowers not reach you?

I made a journey, and passed many a moonlit night in a house beside a bamboo wood. Wind rustled its leaves and my sleep was disturbed.

Night after night the bamboo leaves sigh,

My dreams are broken and a vague, indefinite sadness fills my heart.

In Autumn [1026] I went to live elsewhere and sent a poem:

I am like dew on the grass—

And pitiable wherever I may be—

But especially am I oppressed with sadness

In a field with a thin growth of reeds.

After that time I was somehow restless and forgot about the romances. My mind became more sober and I passed many years without doing any remarkable thing. I neglected religious services and temple observances. Those fantastic ideas [of the romances] can they be realized in this world? If father could win some good position I also might enter into a much nobler life. Such unreliable hopes then occupied my daily thoughts.

At last[44] father was appointed Governor of a Province very far in the East.

[Here the diary skips six years. The following is reminiscent.]

He [father] said: “I was always thinking that if I could win a position as Governor in the neighbourhood of the Capital I could take care of you to my heart’s desire. I would wish to bring you down to see beautiful scenery of sea and mountain. Moreover, I wished that you could live attended beyond [the possibilities] of our [present] position. Our Karma relation from our former world must have been bad. Now I have to go to so distant a country after waiting so long! When I brought you, who were a little child, to the Eastern Province [at his former appointment], even a slight illness caused me much trouble of mind in thinking that should I die, you would wander helpless in that far country. There were many fears in a stranger’s country, and I should have lived with an easier mind had I been alone. As I was then accompanied by all my family, I could not say or do what I wanted to say or do, and I was ashamed of it. Now you are grown up [she was twenty-five years old] and I am not sure that I can live long.