Thus far we’ve established why it’s important to slow down your thinking and avoid rushing to judgment about topics. We’ve demonstrated how a close, careful, critical reading of texts can produce greater insights. We’ve explored the interplay among academic disciplines and shown how using various disciplinary lenses can lead us to see the world in different ways. We haven’t yet turned these private thinking exercises into public writing. It’s time to go public and join the conversation.

Because they have presented critical thinking strategies, the first three chapters have only occasionally touched on the stakes involved in actually presenting your ideas publicly. In this final chapter, you will learn what’s involved in using rhetoric to write for a specific audience and purpose.

Raising the Stakes by Going Public

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the fact that rhetoric is value-neutral and ever present.

- Understand the relationship between dialectic and rhetoric.

- Learn about the differences between low-stakes private writing and high-stakes public writing.

The word rhetoric, like critical, has taken on a negative connotation in recent years. Politicians are fond of using the (ironically rhetorical) technique of boasting that they will “not indulge in rhetoric,” or accusing their opponents of “being rhetorical,” as if it were possible to communicate at all without using rhetoric. Rhetoric is simply a value-neutral term for communication that has a purpose. It can be used in the service of good or evil, or something in between, but it is always used. Communicating publicly without using rhetoric is like driving across town without a car.

Just as you used writing to think in the first three chapters, when you write publicly in this chapter and beyond, you shouldn’t stop thinking. Sometimes public and academic writing is presented as a fixed, sterile transcript or translation of already completed thoughts. But the more faithfully you depict your thinking process in front of your readers, the more engaged your audience will be, and the more they will want to share in your journey.

Dialectic and Rhetoric

In Chapter 3 “Thinking through the Disciplines”, we explored how disciplines navigate between binary oppositions to sustain dialogue, debate, and the possibility of new discoveries. The classical term for sustaining a productive tension between binary oppositions is dialectic, from the Greek word meaning “dialogue.” We have been suggesting that you could use dialectic in your academic pursuits as a way of understanding concepts and perhaps even producing new insights.

A good working knowledge of the methods and strategies of rhetoric will put you in position to apply, translate, and convey publicly the insights you generate through dialectic thinking. In classical terms, dialectic and rhetoric were considered to be complementary counterparts. If you merely think dialectically without eventually using public rhetoric, your insights will be isolated and irrelevant. On the other hand, if you use only rhetoric without first going through some rigorously dialectical thinking, your communication will be undisciplined, shallow, overly partial and subjective, and lacking in perspective. An educated, ethical person needs to use both dialectic and rhetoric in order to engage fully with the world.

Moving from Low-Stakes to High-Stakes Writing

Let’s bring these ideas down to earth with an example of how a semiprivate journal entry was partially but not completely transformed into a piece of public communication in an academic setting. In the first couple of weeks of the semester, Zach, a first-year college writing student, wrote the following entry in his electronic writing journal (a space that had been set up for “semiprivate” communication between students and their instructor, with an understanding that the instructor would neither grade the entries nor comment on them unless invited to do so):

Two days ago, when my mother got laid off, I was notified that my paycheck was now, not only the primary and bread-winning income, but the ONLY income. This is really putting stress onto me and because of this means two of everything, for example two car payments, twice the insurance, the entire phone bill, and the entire rent amount.

Later in the term, when students were invited to post suggestions for the next year’s entering class of students on a class-wide wiki, Zach decided to go public with his story (embedded in his new, now public post).

Strategies for Success in Community College

Many incoming community college students enter into their freshman year with the part-time job that they acquired in their senior year of high school. For me, entering into the new college environment with a full-time job has been a bit of a hassle as well as being quite stressful. When I started my freshman year, my job paid my share of the rent and phone bill as well as my car payment and insurance payment.

Early in the semester, when my mother got laid off, I was notified that my paycheck was now, not only the primary and bread-winning income, but the ONLY income. This is really putting stress onto me and because of this means two of everything, for example two car payments, twice the insurance, the entire phone bill, and the entire rent amount.

When you start your college careers, you must pace yourself when you take your first semester of classes. It is best to put your job on the back burner. You do not want to start following me down the bumpy road of life. The path I have chosen has been extremely stressful. In choosing this path, I am close to not only losing my job but I am also dangerously close to failing out of some of my classes. A full-time job as well as being a full-time student is NOT recommended, especially for a first-time student.

Going public with his personal difficulty and addressing an audience (other than himself and his professor) has prompted Zach to begin considering in some detail the dialectic tensions many of his fellow students face between school and work, school and family, and family and work. This deepening of his thinking from pure narrative (“x happened, then y happened”) into analysis (“this is why x and y happened and how they relate to each other”) is an example of how rhetorical responsibility can raise the stakes and the quality of a piece of writing.

However, Zach hasn’t yet moved fully into a rhetorical mode with this post because he is still working through the various dialectics he has raised. He has actually gone public too early in the process, before he has come up with some reasonably meaningful and complete ideas to convey to his newly recruited audience. He has closed with an incontrovertibly true statement: “A full-time job as well as being a full-time student is NOT recommended, especially for a first-time student.” But he hasn’t yet worked out an alternative to that arrangement that also meets the needs of his family. The wiki post is, more realistically, step two of a multistep process. Now that he has an audience in mind and a clear sense of his dilemma, he needs to explore a realistic and sustainable solution to this problem on a wider scale.

Key Takeaways

- Rhetoric is the public application of dialectical thinking.

- Low-stakes, private writing that explores the terms of a dialectic can be transformed into high-stakes, public writing meant for an audience, but that process may take several stages or drafts.

- The process of going public involves a balance between meeting your audience’s expectations and honoring your original thinking process.

Exercises

- Uncover a dialectic tension in a piece of your journal writing. Lay out a plan for how you could move from dialectic to rhetoric. How would you explore this dialectic further and ultimately present it rhetorically to an audience of your choosing? If appropriate, execute your plan.

- Review a piece of “finished” text, either an essay you’ve already produced for an audience or grade or a published piece by another writer. Identify a dialectic tension in the piece that was oversimplified or dismissed in the interest of “going public” prematurely. Use your findings to lay out a plan to move from rhetoric back to dialectic and then move back to a more balanced, effective, meaningful use of rhetoric.

-

Revise the following semiprivate journal entry about juggling work, family, and school into a public wiki post for an audience of entering college students. Use the following steps:

- Examine the journal for any dialectic tensions and identify them.

- Decide whether you have fully worked out those dialectics in the current draft.

- As you go public, figure out how to present the dialectics with rhetorical effectiveness.

Sometimes going to school full time and trying to make money is difficult and to do it I have to juggle my responsibilities and manage my time appropriately. A big problem I have is when I am working I am often too exhausted to spend the necessary amount of concentration I need to on my school work. I work for my parents remodeling my house which includes a lot of physical labor such as painting, putting down flooring, refinishing cabinets, and so forth. These things drain a lot of energy out of me and make it hard to study and focus at night. I have been doing a mediocre job keeping up with school and work but would like to be able to make improvements in both without being so tired.

To do this I started alternating between doing school work in the afternoons and working in the mornings. Instead of during a bunch of physical labor early in the day and tiring my self out by night time when it was time to do my homework I switched the two. I started my day out by making a list of all the homework I needed to do that day and then did half of it. After I completed half of my homework I would do the work I was suppose to around my house until everything that needed to be done that day was done. After I finished my work I took a break and ate. I left myself a couple hours to relax or socialize before I had to finish the rest of my homework. This schedule left me with a lot more energy at night and less homework to do which let me put more attention and focus into actually understanding the homework and completing the assignments. Alternating between different things depending on my energy level and time of day has been a helpful strategy for me to overcome my major time-management problem for this week.

Recognizing the Rhetorical Situation

Learning Objectives

- Outline and illustrate the elements of the rhetorical triangle.

- Explore the uses and abuses of rhetorical appeals.

- Show how to develop the habit of thinking rhetorically.

The term argument, like rhetoric and critical, is another term that can carry negative connotations (e.g., “We argued all day,” “He picked an argument,” or “You don’t have to be so argumentative”), but like these other terms, it’s really just a neutral term. It’s the effort to use rhetorical appeals to influence an audience and achieve a certain set of purposes and outcomes.

The Rhetorical Triangle

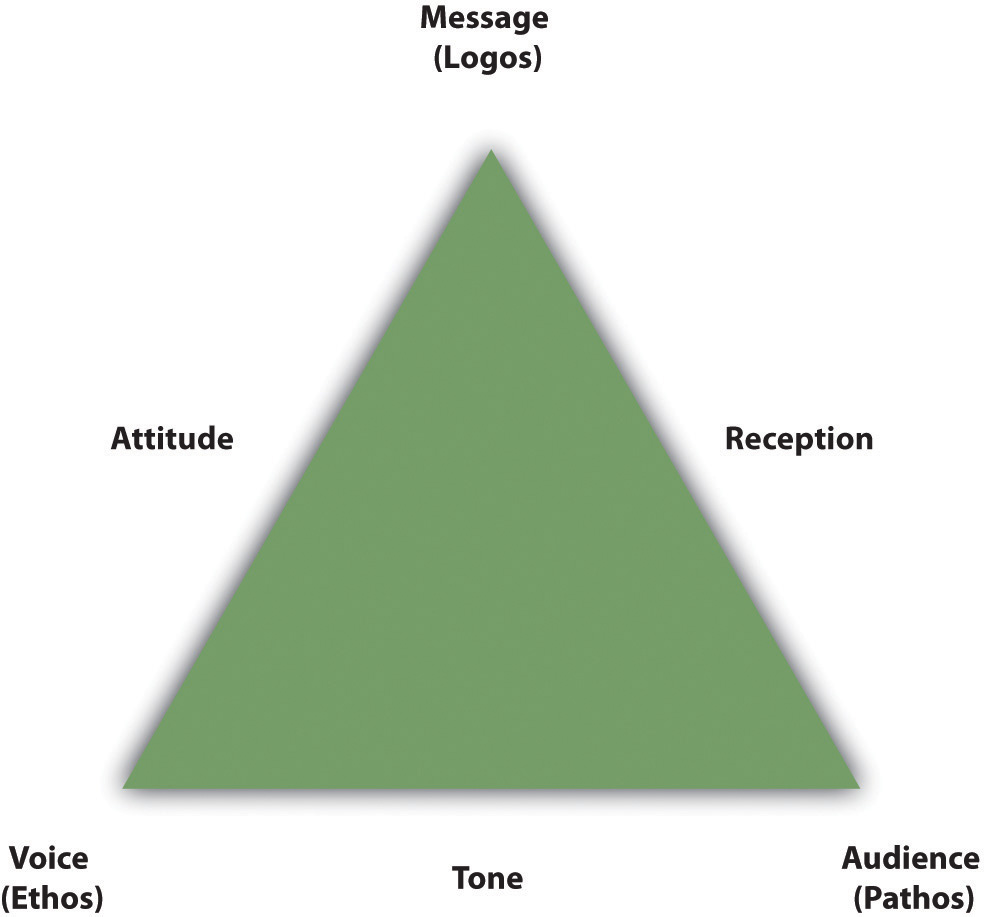

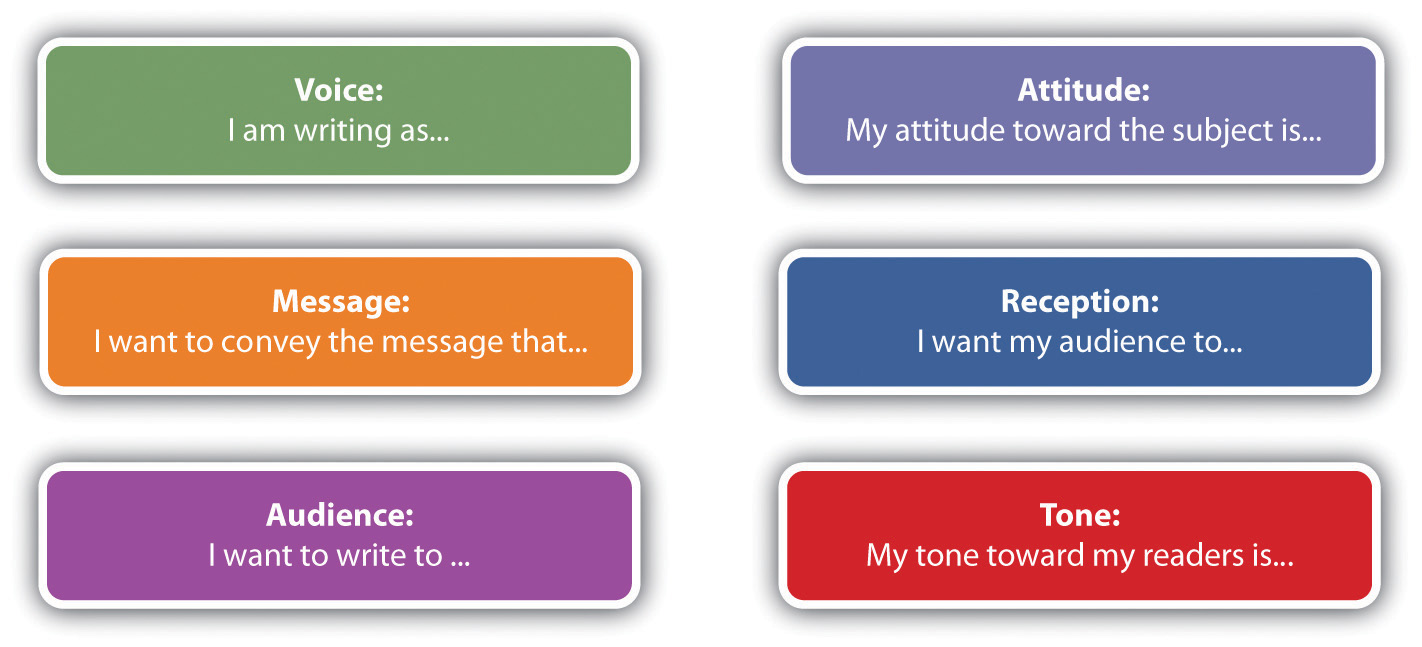

The principles Aristotle laid out in his Rhetoric nearly 2,500 years ago still form the foundation of much of our contemporary practice of argument. The rhetorical situation Aristotle argued was present in any piece of communication is often illustrated with a triangle to suggest the interdependent relationships among its three elements: the voice (the speaker or writer), the audience (the intended listeners or readers), and the message (the text being conveyed).

If each corner of the triangle is represented by one of the three elements of the rhetorical situation, then each side of the triangle depicts a particular relationship between two elements:

- Tone. The connection established between the voice and the audience.

- Attitude. The orientation of the voice toward the message it wants to convey.

- Reception. The manner in which the audience receives the message conveyed.

Rhetorical Appeals

In this section, we’ll focus on how the rhetorical triangle can be used in service of argumentation, especially through the balanced use of ethical, logical, and emotional appeals: ethos, logos, and pathos, respectively. In the preceding figure, you’ll note that each appeal has been placed next to the corner of the triangle with which it is most closely associated:

- Ethos. Appeals to the credibility, reputation, and trustworthiness of the speaker or writer (most closely associated with the voice).

- Pathos. Appeals to the emotions and cultural beliefs of the listeners or readers (most closely associated with the audience).

- Logos. Appeals to reason, logic, and facts in the argument (most closely associated with the message).

Each of these appeals relies on a certain type of evidence: ethical, emotional, or logical. Based on your audience and purpose, you have to decide what combination of techniques will work best as you present your case.

When using a logical appeal, make sure to use sound inductive and deductive reasoning to speak to the reader’s common sense. Specifically avoid using emotional comments or pictures if you think your audience will see their use as manipulative or inflammatory. For example, in an essay proposing that participating in high school athletics helps students develop into more successful students, you could show graphs comparing the grades of athletes and nonathletes, as well as high school graduation rates and post–high school education enrollment. These statistics would support your points in a logical way and would probably work well with a school board that is considering cutting a sports program.

The goal of an emotional appeal is to garner sympathy, develop anger, instill pride, inspire happiness, or trigger other emotions. When you choose this method, your goal is for your audience to react emotionally regardless of what they might think logically. In some situations, invoking an emotional appeal is a reasonable choice. For example, if you were trying to convince your audience that a certain drug is dangerous to take, you might choose to show a harrowing image of a person who has had a bad reaction to the drug. In this case, the image draws an emotional appeal and helps convince the audience that the drug is dangerous. Unfortunately, emotional appeals are also often used unethically to sway opinions without solid reasoning.

An ethical appeal relies on the credibility of the author. For example, a college professor who places a college logo on a website gains some immediate credibility from being associated with the college. An advertisement for tennis shoes using a well-known athlete gains some credibility. You might create an ethical appeal in an essay on solving a campus problem by noting that you are serving in student government. Ethical appeals can add an important component to your argument, but keep in mind that ethical appeals are only as strong as the credibility of the association being made.

Whether your argument relies primarily on logos, pathos, ethos, or a combination of these appeals, plan to make your case with your entire arsenal of facts, statistics, examples, anecdotes, illustrations, figurative language, quotations, expert opinions, discountable opposing views, and common ground with the audience. Carefully choosing these supporting details will control the tone of your paper as well as the success of your argument.

Logical, Emotional, and Ethical Fallacies

Rhetorical appeals have power. They can be used to motivate or to manipulate. When they are used irresponsibly, they lead to fallacies. Fallacies are, at best, unintentional reasoning errors, and at worst, they are deliberate attempts to deceive. Fallacies are commonly used in advertising and politics, but they are not acceptable in academic arguments. The following are some examples of three kinds of fallacies that abuse the power of logical, emotional, or ethical appeals (logos, pathos, or ethos).

| Logical Fallacies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Begging the question (or circular reasoning): The point is simply restated in different words as proof to support the point. | Tall people are more successful because they accomplish more. |

| Either/or fallacy: A situation is presented as an “either/or” choice when in reality, there are more than just two options. | Either I start to college this fall or I work in a factory for the rest of my life. |

| False analogy: A comparison is made between two things that are not enough alike to support the comparison. | This summer camp job is like a rat cage. They feed us and let us out on a schedule. |

| Hasty generalization: A conclusion is reached with insufficient evidence. | I wouldn’t go to that college if I were you because it is extremely unorganized. I had to apply twice because they lost my first application. |

| non sequitur: Two unrelated ideas are erroneously shown to have a cause-and-effect relationship. | If you like dogs, you would like a pet lion. |

| post hoc ergo propter hoc (or false cause and effect): The writer argues that A caused B because B happened after A. | George W. Bush was elected after Bill Clinton, so it is clear that dissatisfaction with Clinton lead to Bush’s election. |

| Red herring: The writer inserts an irrelevant detail into an argument to divert the reader’s attention from the main issue. | My room might be a mess, but I got an A in math. |

| Self-contradiction: One part of the writer’s argument directly contradicts the overall argument. | Man has evolved to the point that we clearly understand that there is no such thing as evolution. |

| Straw man: The writer rebuts a competing claim by offering an exaggerated or oversimplified version of it. | Claim—You should take a long walk every day. Rebuttal—You want me to sell my car, or what? |

| Emotional Fallacies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Apple polishing: Flattery of the audience is disguised as a reason for accepting a claim. | You should wear a fedora. You have the perfect bone structure for it. |

| Flattery: The writer suggests that readers with certain positive traits would naturally agree with the writer’s point. | You are a calm and collected person, so you can probably understand what I am saying. |

| Group think (or group appeal): The reader is encouraged to decide about an issue based on identification with a popular, high-status group. | The varsity football players all bought some of our fundraising candy. Do you want to buy some? |

| Riding the bandwagon: The writer suggests that since “everyone” is doing something, the reader should do it too. | The hot thing today is to wear black socks with tennis shoes. You’ll look really out of it if you wear those white socks. |

| Scare tactics (or veiled threats): The writer uses frightening ideas to scare readers into agreeing or believing something. | If the garbage collection rates are not increased, your garbage will likely start piling up. |

| Stereotyping: The writer uses a sweeping, general statement about a group of people in order to prove a point. |

Women won’t like this movie because it has too much action and violence. OR Men won’t like this movie because it’s about feelings and relationships. |

| Ethical Fallacies | Examples |

|---|---|

| Argument from outrage: Extreme outrage that springs from an overbearing reliance on the writer’s own subjective perspective is used to shock readers into agreeing instead of thinking for themselves. | I was absolutely beside myself to think that anyone could be stupid enough to believe that the Ellis Corporation would live up to its commitments. The totally unethical management there failed to require the metal grade they agreed to. This horrendous mess we now have is completely their fault, and they must be held accountable. |

| False authority (or hero worship or appeal to authority or appeal to celebrity): A celebrity is quoted or hired to support a product or idea in efforts to sway others’ opinions. | LeBron James wears Nikes, and you should too. |

| Guilt by association: An adversary’s credibility is attacked because the person has friends or relatives who possibly lack in credibility. | We do not want people like her teaching our kids. Her father is in prison for murder. |

| Personal attack (or ad hominem): An adversary’s personal attributes are used to discredit his or her argument. | I don’t care if the government hired her as an expert. If she doesn’t know enough not to wear jeans to court, I don’t trust her judgment about anything. |

| Poisoning the well: Negative information is shared about an adversary so others will later discredit his or her opinions. | I heard that he was charged with aggravated assault last year, and his rich parents got him off. |

| Scapegoating: A certain group or person is unfairly blamed for all sorts of problems. | Jake is such a terrible student government president; it is no wonder that it is raining today and our spring dance will be ruined. |

Do your best to avoid using these examples of fallacious reasoning, and be alert to their use by others so that you aren’t “tricked” into a line of unsound reasoning. Getting into the habit of reading academic, commercial, and political rhetoric carefully will enable you to see through manipulative, fallacious uses of verbal, written, and visual language. Being on guard for these fallacies will make you a more proficient college student, a smarter consumer, and a more careful voter, citizen, and member of your community.

Key Takeaways

- The principles of the rhetorical situation outlined in Aristotle’s Rhetoric almost 2,500 years ago still influence the way we look at rhetoric today, especially the interdependent relationships between voice (the speaker or writer), message (the text being conveyed), and audience (the intended listeners or readers).

- The specific relationships in the rhetorical triangle can be called tone (voice–audience), attitude (voice–message), and reception (audience–message).

- Rhetorical appeals can be used responsibly as a means of building a persuasive argument, but they can also be abused in fallacies that manipulate and deceive unsuspecting audiences.

Exercises

- Apply what you’ve learned about the uses and abuses of rhetorical appeals (logos, pathos, and ethos) to a text from the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts”. For good examples from advertising, politics, history, and government, try the Ad Council, the Avalon Project, From Revolution to Reconstruction, The Living Room Candidate, or the C-SPAN Video Library. For example, The Living Room Candidate site allows you to survey television ads from any presidential campaign since 1952. You could study five ads for each of the major candidates and subject the ads to a thorough review of their use of rhetorical techniques. Cite how and where each ad uses each of the three rhetorical appeals, and determine whether you think each ad uses the appeals manipulatively or legitimately. In this case, subject your political biases and preconceptions to a review as well. Is your view of one candidate’s advertising more charitable than the other for any subjective reason?

- Find five recent print, television, or web-based advertisements and subject them to a thorough review of their use of rhetorical techniques. Determine whether you think each advertisement uses rhetorical appeals responsibly and effectively or misuses the appeals through fallacies. Identify the appeals employed in either case.

-

In the following passage from Thomas Paine’s famous 1776 pamphlet, Common Sense, discuss Paine’s use of rhetorical appeals. Which of the three appeals (logos, pathos, or ethos) predominates, and why? For the context of this passage, go to From Revolution to Reconstruction in the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” and search for Paine, or click on http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/D/1776-1800/paine/CM/sense04.htm to go to the passage directly:

Europe is too thickly planted with kingdoms to be long at peace, and whenever a war breaks out between England and any foreign power, the trade of America goes to ruin, because of her connection with Britain. The next war may not turn out like the Past, and should it not, the advocates for reconciliation now will be wishing for separation then, because, neutrality in that case, would be a safer convoy than a man of war. Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ’TIS TIME TO PART. Even the distance at which the Almighty hath placed England and America, is a strong and natural proof, that the authority of the one, over the other, was never the design of Heaven.

American colonists faced a dialectic between continuing to be ruled by Great Britain or declaring independence. Arguments in favor of independence (such as Paine’s) are quite familiar to students of American history; the other side of the dialectic, which did not prevail, will likely be less so. In the following passage, Charles Inglis, in his 1776 pamphlet, The True Interest of America Impartially Stated, makes a case for ending the rebellion and reconciling with Great Britain. At one point in the passage, Inglis quotes Paine directly (calling him “this author”) as part of his rebuttal. As in the preceding exercise, read the passage and discuss its use of rhetorical appeals. Again, which of the three appeals (logos, pathos, or ethos) predominates, and why? For a link to the entire Inglis document, search for Inglis in From Revolution to Reconstruction in the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts”, or click on http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/D/1776-1800/libertydebate/inglis.htm to go to the link directly:

By a reconciliation with Britain, a period would be put to the present calamitous war, by which so many lives have been lost, and so many more must be lost, if it continues. This alone is an advantage devoutly to be wished for. This author says, “The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, Tis time to part.” I think they cry just the reverse. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries—It is time to be reconciled; it is time to lay aside those animosities which have pushed on Britons to shed the blood of Britons; it is high time that those who are connected by the endearing ties of religion, kindred and country, should resume their former friendship, and be united in the bond of mutual affection, as their interests are inseparably united.

Rhetoric and Argumentation

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the various methods, types, and aims of argumentation used in academic and professional texts.

- Understand how to adjust your approach to argumentation depending on your rhetorical situation and the findings of your research.

True argumentation is the most important kind of communication in the academic and professional world. Used effectively, it is how ideas are debated and shared in discourse communities. Argumentation holds both writers and readers to the highest standards of responsibility and ethics. It is usually not what you see on cable news shows or, sadly, even in presidential debates. This section will show how rhetoric is used in service of argumentation.

Induction and Deduction

Traditionally, arguments are classified as either inductive or deductive. Inductive arguments consider a number of results and form a generalization based on those results. In other words, say you sat outside a classroom building and tallied the number of students wearing jeans and the number wearing something other than jeans. If after one hour, you had tallied 360 students wearing jeans and 32 wearing other clothes, you could use inductive reasoning to make the generalization that most students at your college wear jeans to class. Here’s another example. While waiting for your little sister to come out of the high school, you saw 14 girls wearing high heels. So you assume that high heels are standard wear for today’s high school girls.

Deductive arguments begin with a general principle, which is referred to as a major premise. Then a related premise is applied to the major premise and a conclusion is formed. The three statements together form a syllogism. Here are some examples:

- Major premise: Leather purses last a long time.

- Minor premise: I have a leather purse.

- Conclusion: My purse will last a long time.

- Major premise: Tara watches a lot of television.

- Minor premise: Tara is a very good student.

- Conclusion: A teenager can be a good student even if he or she watches a lot of television.

Although these simple inductive and deductive arguments are fairly clean and easy to follow, they can be flawed because of their rigidity.

Let’s revisit the “college students wear jeans” argument. What if you happened to be counting jeans wearers on a day that has been declared Denim Appreciation Day? Or conversely, what if you had taken the sample on the hottest day of the year in the middle of the summer session? Although it might be true that most students in your sample on that day wore jeans to class, the argument as it stands is not yet strong enough to support the statement.

Now consider the purse argument. The argument is not strong since a variety of possible exceptions are obvious. First, not all leather purses last a long time since the leather could be strong, but the workmanship could be shoddy (challenge to major premise). Second, the quality of the leather in your particular purse could be such that it would not hold up to heavy use (challenge to minor premise). Third, a possible exception is that the argument does not take into account how long I have had my purse: even though it is made of leather, its lifespan could be about over. Since very few issues are completely straightforward, it is often easy to imagine exceptions to simplistic arguments. For this reason, somewhat complex argument forms have been developed to address more complicated issues that require some flexibility.

Types of Argumentation

Three common types of argumentation are classical, Toulmin, and Rogerian. You can choose which type to use based on the nature of your argument, the opinions of your audience, and the relationship between your argument and your audience.

The typical format for a classical argument will likely be familiar to you:

-

Introduction

- Convince readers that the topic is worthy of their attention.

- Provide background information that sets the stage for the argument.

- Provide details that show you as a credible source.

- End with a thesis statement that takes a position on the issue or problem you have established to be arguable.

-

Presentation of position

- Give the reasons why the reader should share your opinion.

- Provide support for the reasons.

- Show why the reasons matter to the audience.

-

Presentation and rebuttal of alternative positions

- Show that you are aware of opposing views.

- Systematically present the advantages and disadvantages of the opposing views.

- Show that you have been thorough and fair but clearly have made the correct choice with the stand you have taken.

-

Conclusion

- Summarize your argument.

- Make a direct request for audience support.

- Reiterate your credentials.

Toulminian argumentation (named for its creator, Stephen Toulmin) includes three components: a claim, stated grounds to support the claim, and unstated assumptions called warrants. Here’s an example:

- Claim: All homeowners can benefit from double-pane windows.

- Grounds: Double-pane windows are much more energy efficient than single-pane windows. Also, double-pane windows block distracting outside noise.

- Warrant: Double-pane windows keep houses cooler in summer and warmer in winter, and they qualify for the tax break for energy-efficient home improvements.

The purest version of Rogerian argumentation (named for its creator, Carl Rogers) actually aims for true compromise between two positions. It can be particularly appropriate when the dialectic you are addressing remains truly unresolved. However, the Rogerian method has been put into service as a motivational technique, as in this example:

- Core argument: First-semester college students should be required to attend three writing sessions in the college writing center.

- Common ground: Many first-semester college students struggle with college-level work and the overall transition from high school to college.

- Link between common ground and core argument: We want our students to have every chance to succeed, and students who attend at least three writing sessions in the university writing lab are 90 percent more likely to succeed in college.

Rogerian argumentation can also be an effective standard debating technique when you are arguing for a specific point of view. Begin by stating the opposing view to capture the attention of audience members who hold that position and then show how it shares common ground with your side of the point. Your goal is to persuade your audience to come to accept your point by the time they read to the end of your argument. Applying this variation to the preceding example might mean leading off with your audience’s greatest misgivings about attending the writing center, by opening with something like “First-semester college students are so busy that they should not be asked to do anything they do not really need to do.”

Analytical and Problem-Solving Argumentation

Arguments of any kind are likely to either take a position about an issue or present a solution to a problem. Don’t be surprised, though, if you end up doing both. If your goal is to analyze a text or a body of data and justify your interpretation with evidence, you are writing an analytical argument. Examples include the following:

- Evaluative reviews (of restaurants, films, political candidates, etc.)

- Interpretations of texts (a short story, poem, painting, piece of music, etc.)

- Analyses of the causes and effects of events (9/11, the Civil War, unemployment, etc.)

Problem-solving argumentation is not only the most complicated but also the most important type of all. It involves several thresholds of proof. First, you have to convince readers that a problem exists. Second, you have to give a convincing description of the problem. Third, because problems often have more than one solution, you have to convince readers that your solution is the most feasible and effective. Think about the different opinions people might hold about the severity, causes, and possible solutions to these sample problems:

- Global warming

- Nonrenewable energy consumption

- The federal budget deficit

- Homelessness

- Rates of personal saving

Argumentation often requires a combination of analytical and problem-solving approaches. Whether the assignment requires you to analyze, solve a problem, or both, your goal is to present your facts or solution confidently, clearly, and completely. Despite the common root word, when writing an argument, you need to guard against taking a too argumentative tone. You need to support your statements with evidence but do so without being unduly abrasive. Good argumentation allows us to disagree without being disagreeable.

Research and Revision in Argumentation

Your college professors are not interested in having you do in-depth research for its own sake, just to prove that you know how to incorporate a certain number of sources and document them appropriately. It is assumed that extensive research is a core feature of a strong essay. In college-level writing, research is not meant merely to provide additional support for an already fixed idea you have about the topic, or to set up a “straw man” for you to knock down with ease. Don’t fall into the trap of trying to make your research fit your existing argument. Research conducted in good faith will almost certainly lead you to refine your ideas about your topic, leading to multiple revisions of your work. It might cause you even to change your topic entirely.

Revision is part of the design of higher education. If you embrace the “writing to think” and “writing to learn” philosophy and adopt the “composing habits of mind” with each draft, you will likely rethink your positions, do additional research, and make other general changes. As you conduct additional research between drafts, you are likely to find new information that will lead you to revise your core argument. Let your research drive your work, and keep in mind that your argument will remain in flux until your final draft. In the end, every final draft you produce should feel like a small piece of a vast and never ending conversation.

Key Takeaways

- Argumentative reasoning relies on deduction (using multiple pieces of evidence to arrive at a single conclusion) and induction (arriving at a general conclusion from specific facts).

- You must decide which type of argumentation (classical, Toulmin, or Rogerian) is most appropriate for the rhetorical situation (voice, audience, message, tone, attitude, and reception).

- Analytical argumentation looks at a body of evidence and takes a position about it, while problem-solving argumentation tries to present a solution to a problem. These two aims of argumentation lead to very different kinds of evidence and organizational approaches.

- In argumentation, it’s especially important for you to be willing to adjust your approach and even your position in the face of new evidence or new circumstances.

Exercises

-

Drawing from one of your college library databases, find two texts you consider to be serious efforts at academic or professional argumentation. Write up a report about the types of argumentation used in each of the two texts. Answer the following questions and give examples to support your answers:

- Does the text use primarily inductive or deductive argumentation?

- Does it use classical, Toulmin, or Rogerian argumentation?

- Is it primarily analytical or problem-solving argumentation?

-

With your writing group or in a large-class discussion, discuss the types of argumentation that would be most appropriate and effective for addressing the following issues:

- Capital punishment

- Abortion

- The legal drinking age

- Climate change

- Campus security

-

Come up with a controversial subject and write about how you would treat it differently depending on whether you used each of the following:

- Inductive or deductive reasoning

- Classical, Toulmin, or Rogerian argumentation

- An analytical or a problem-solving approach

4.4 Developing a Rhetorical Habit of Mind

Learning Objectives

- Get into the habit of thinking about the all texts in rhetorical terms.

- Learn about the statement of purpose and how it can be used as a tool for your future academic and professional writing.

- Develop a rhetorical habit of mind by enhancing your awareness of how language works.

The habit of thinking rhetorically starts with being comfortable enough with the rhetorical triangle to see it in practically every form of communication you produce and consume—not only those you encounter in academic settings but also those you encounter in everyday life.

Besides familiarizing yourself with the elements of the triangle and how they function, you’ll also need to consider the rhetorical moves writers make so you can begin to use language more creatively in your writing. Good writers learn to improvise with the language, to make it work both as a tool for thinking and as a vehicle for communication. Here are four categories of rhetorical moves you will encounter and begin to use as you develop a rhetorical habit of mind.

| Rhetorical Move and Definition | Examples |

|---|---|

|

Connotative language: Using a word beyond its denotation (or primary definition) to suggest or incite a desired response in readers. Sometimes a connotation can be a euphemism designed to make something sound better than it really is; at other times, a connotation can put a negative spin on something. |

“welfare” (or “entitlement”) |

| “economic stimulus” (or “recovery”) | |

| “death panel” (or “managed care”) | |

| “pro-choice” (or “pro-abortion”) | |

| “estate tax” (or “death tax”) | |

| “global warming” (or “greenhouse effect”) | |

|

Figurative language: Using metaphors, similes, and analogies can help you and your readers uncover previously unseen connections between different categories of things. |

“That professor’s lecture was like a metronome.” (Similes use like or as.) |

| “That test was a bear.” (Metaphors don’t.) | |

| “The current panic in education about students’ addiction to texting and video games is reminiscent of concerns in earlier eras about other kinds of emerging technology.” (Analogies can lead to entire essay topics.) | |

|

Humorous language: Audiences who are entertained are more likely to receive your message. Within reason and boundaries of taste, there’s nothing wrong with using wit to help you make your points. Examples include plays on words (like puns, slang, neologisms, or “new words”), as well as more elaborate kinds of humor (such as parody and satire). |

Recent additions to the dictionary (like “telecommuting,” “sexting,” and “crowdsourcing”) usually began as plays on words. |

| Parody and satire are ironic ways of imitating a subject or style through caricature and exaggeration. | |

| Note: These kinds of humor require precise knowledge of your audience’s readiness to be entertained in this way. They can easily backfire and turn sour, but when used carefully, they can be extremely effective. | |

|

Metacognitive language: Thinking about your thinking (metacognition) can help you step outside yourself to reflect on your writing (the equivalent of “showing your work” in math). |

“At this point, I’d like to be clear about my intentions for this essay…” |

| “Before I began this research project, I thought…but now I’ve come to believe…” |

As you survey this table, remember that clear, simple, direct communication is still your primary goal, so don’t try all these techniques in the same piece of writing. Just know that you have them at your disposal and begin to develop them as part of your toolkit of rhetorical moves.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a rhetorical habit of mind will help you consider voice, audience, message, tone, attitude, and reception in all the texts you read and write.

- The rhetorical habit of mind will also help you recognize rhetorical moves in four categories of language use: connotative, figurative, humorous, and metacognitive.

- In the process of developing the rhetorical habit of mind, you will also develop your creativity, sense of humor, and self-awareness.

Exercises

- Use the chart at the end of this section to find at least one example from each of the four categories of rhetorical moves in a reading of your choice. Be prepared to present your findings in a journal entry, a blog post, or as part of a group or class-wide discussion.

- Take a piece of your writing in progress and try to incorporate at least one rhetorical move from each category into it, using the chart at the end of this section as a guide.

Candela Citations

- Joining the Conversation. Authored by: Withheld by Lardbucket at Publishers' Request (see https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/writers-handbook/). Provided by: Lardbucket. Located at: https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/writers-handbook/s08-joining-the-conversation.html. Project: Writers' Handbook. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike