Writing to Think and Writing to Learn

Which Comes First? A Chicken-or-the-Egg Question

You’ve probably had moments as a writing student when you’ve said to yourself, “I know what I think about this topic; I just can’t get it down on paper.” This frustration comes from the notion that writing comes after thinking, that it merely represents or translates thoughts that are already fully formed in your head. But what if the act of writing helps sharpen your thinking? What if the act of putting thoughts into words changes those thoughts for the better? Are there ways to make that transformation happen consistently enough so that writing becomes not an end but a beginning, not a chore but a revelation? That’s what this first chapter is about.

1.1 Examining the Status Quo

Learning Objectives

- Understand your roles and responsibilities as a person engaged in higher education.

- Explore the relationship between higher education and the status quo.

- Learn ways to examine the status quo in your surroundings consistently and productively.

Why are you here?

The question sounds simple enough, and you may well have developed some stock answers by now.

I’m here because…

- I want to be a ______________ when I grow up.

- college graduates make more money.

- my parents wanted me to go here.

- my boyfriend or girlfriend got accepted here.

- I couldn’t get in anywhere else.

- I just got laid off.

Maybe the truth is, deep down, that you don’t really know yet why you’re here, and that’s OK. By the end of your college experience, you’ll have developed several good answers for why you were here, and they won’t necessarily look anything like your first stock response.

But what does this personal question about your motivations for being in college have to do with examining the status quo? Well, the first way to learn how to examine the status quo (literally, “the state in which”) is to examine your place in it. By enrolling in higher education, you’re making a choice to develop your skills and intellect beyond a baseline level of proficiency. Choosing to become a college-educated person obligates you to leave your mark on the world.

You’re investing time and money into your college education, presumably for the real benefits it will provide you, but it’s important to remember that others are investing in you as well. Perhaps family members are providing financial support, or the federal government is providing a Pell Grant or a low-interest loan, or an organization or alumni group is awarding you a scholarship. If you’re attending a state school, the state government is investing in you because your tuition (believe it or not) covers only a small portion of the total cost to educate you.

So what is the return a free, independent, evolving society expects on its investment in you, and what should you be asking of yourself? Surely something more than mere maintenance of the status quo should be in order. Rather, society expects you to be a member of a college-educated citizenry and workforce capable of improving the lives and lot of future generations.

Getting into the habit of “examining” (or even “challenging”) the status quo doesn’t necessarily mean putting yourself into a constant state of revolution or rebellion. Rather, the process suggests a kind of mindfulness, a certain disposition to ask a set of questions about your surroundings:

- What is the status quo of _________? (descriptive)

- Why is _______ the way it is? (diagnostic)

- What (or who) made ________ this way? (forensic)

- Was _______ ever different in the past? (historical)

- Who benefits from keeping ______ the way it is? (investigative)

Only after these relatively objective questions have been asked, researched, and answered might you hazard a couple of additional, potentially more contentious questions:

- How could or should ______ be different in the future? (speculative)

- What steps would be required to make _______ different? (policy based)

These last two types of questions are more overtly controversial, especially if they are applied to status-quo practices that have been in place for many years or even generations. But asking even the seemingly benign questions in the first category will directly threaten those forces and interests that benefit most from the preservation of the status quo. You will encounter resistance not only from this already powerful group but also from reformers with competing interests who have different opinions about where the status quo came from or how it should be changed.

efore you risk losing heart or nerve for fear of making too many enemies by roiling the waters, think about the benefits the habit of privately examining the status quo might have for your thinking, writing, and learning.

Since we began this section with a discussion about education and your place in it, let’s close by having you exercise this habit on that same subject. For starters, let’s just apply the questioning habit to some of what you may have been taught about academic writing over the years. Here is one description of the status quo thinking on the subject that might be worth some examination.

What Is the Status Quo of Academic Writing?

- Writing can and should be taught and learned in a certain, systematic way.

- Writing has been taught and learned in much the same way over time.

- Becoming a good writer is a matter of learning the forms (genres, modes, etc.) of academic writing.

- Students are blank slates who know next to nothing about how to write.

- Writing done outside of academic settings (e-mail, texting, graffiti, comics, video game design, music lyrics, etc.) is not really writing.

- Knowing what you think is a must before you turn to writing.

- Writing is largely a solitary pursuit.

- Good writing can happen in the absence of good reading.

- Using agreed-on norms and rubrics for evaluation is how experts can measure writing quality based on students’ responses to standardized prompts.

Your list might look a little different, depending on your experience as a student writer. But once you have amassed your description of the status quo, you’re ready to run each element of it through the rest of the mindfulness questions that appear earlier in the section. Or more broadly, you can fill in the blanks of those mindfulness questions with “academic writing” (as you have just described it):

- Why is academic writing the way it is?

- What (or who) made academic writing this way?

- Was academic writing ever different in the past?

- Who benefits from keeping academic writing the way it is?

- How could or should academic writing be different in the future?

- What steps would be required to make academic writing different?

Asking these kinds of questions about a practice like academic writing, or about any of the other subjects you will encounter in college, might seem like a recipe for disaster, especially if you were educated in a K–12 environment that did not value critical questioning of authority. After all, most elementary, middle, and high schools are not in the business of encouraging dissent from their students daily. Yes, there are exceptions, but they are rare, and all the more rare in recent years thanks to the stranglehold of standardized testing and concerns about school discipline. In college, on the other hand, even at the introductory level, the curriculum rewards questioning and perspective about the development and future of the given discipline under examination. Certainly, to be successful at the graduate, postgraduate, and professional level, you must be able to assess, refine, and reform the practices and assumptions of the discipline or profession of which you will be a fully vested member.

Key Takeaways

- You don’t have to know exactly why you’re here in college, but you do have to get into the habit of asking, reasking, and answering that question daily.

- Society’s expected return on its investment in you as a college student (and your expectation of yourself) is that you will be in a position to examine the status quo and when necessary, help change it for the better.

- Learning to ask certain kinds of questions about the status quo will establish a habit of mindfulness and will lead to more productive thinking and writing about your surroundings.

Exercises

- So why are you here? (Be honest, keep it private if you want, but repeat the exercise for the next twenty-eight days and see if your answer changes.)

-

Near the end of this section, you were invited to apply the mindfulness questions to traditional practices in the teaching and learning of academic writing. Now it’s time to try those questions on a topic of your choice or on one of the following topics. Fill in the blank in each case with the chosen topic and answer the resulting question. Keep in mind that this exercise, in some cases, could require a fair amount of research but might also net a pretty substantial essay.

The Mindfulness Questions

- What is the status quo of ________? (descriptive)

- Why is _______ the way it is? (diagnostic)

- What (or who) made ________ this way? (forensic)

- Was _______ ever different in the past? (historical)

- Who benefits from keeping ______ the way it is? (investigative)

- How could or should ______ be different in the future? (speculative)

- What steps would be required to make _______ different? (policy based)

Some Possible Topics

- Fashion (or, if you like, a certain fashion trend or fad)

- Sports (or, if you like, a certain sport)

- Filmmaking

- Video games

- Music (or a particular genre of music)

- Electoral politics

- Internet or computer technology

- US foreign policy

- Health care

- Energy consumption

- Parenting

- Advertising

- A specific academic discipline you are currently studying in another course

- Do some research on an aspect of K–12 or college-level education that you suspect has maintained the status quo for too long. Apply the mindfulness questions to the topic, performing some research and making policy recommendations as necessary.

1.2 Posing Productive Questions

Learning Objectives

- Broaden your understanding of what constitutes a “text” worthy of analysis or interpretation.

- Learn how self, text, and context interact in the process of critical inquiry.

- Explore whether and when seemingly unproductive questions can still produce meaning or significance.

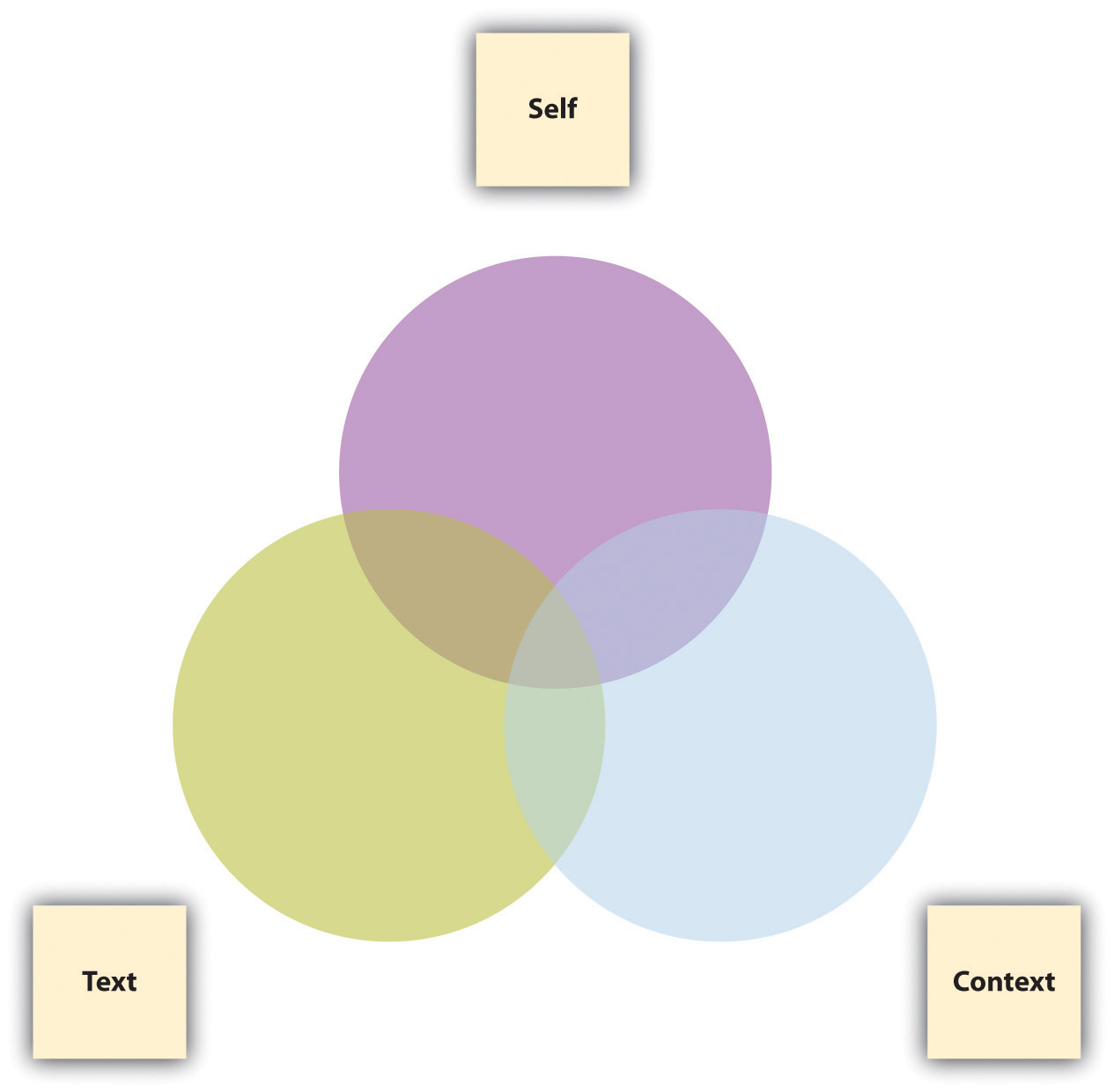

In Section 1.1 “Examining the Status Quo”, we examined the status quo by asking a set of mindfulness questions about a variety of topics. In this section, we’ll explore other ways to open up thinking and writing through the systematic process of critical inquiry. Essentially three elements are involved in any act of questioning:

- The self doing the questioning

- The text about which the questions are being asked

- The context of the text being questioned

For our purposes, text should be defined here very broadly as anything that can be subjected to analysis or interpretation, including but certainly not limited to written texts. Texts can be found everywhere, including but not limited to these areas:

- Music

- Film

- Television

- Video games

- Art and sculpture

- The Internet

- Modern technology

- Advertisement

- Public spaces and architecture

- Politics and government

The following Venn diagram is meant to suggest that relatively simple questions arise when any two out of three of these elements are implicated with each other, while the most complicated, productive questions arise when all three elements are taken into consideration.

Asking the following questions about practically any kind of text will lead to a wealth of ideas, insights, and possible essay topics. As a short assignment in a journal or blog, or perhaps as a group or whole-class exercise, try out these questions by filling in the blanks with a specific text under your examination, perhaps something as common and widely known as “Wikipedia” or “Facebook” or “Google” (for ideas about where to find other texts, see the first exercise at the end of this section).

Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context

Self-Text Questions

- What do I think about ____________?

- What do I feel about ___________?

- What do I understand or what puzzles me in or about ____________?

- What turns me off or amuses me in or about ____________?

- What is predictable or surprises me in or about ____________?

Text-Context Questions

- How is ___________ a product of its culture and historical moment?

- What might be important to know about the creator of ___________?

- How is ___________ affected by the genre and medium to which it belongs?

- What other texts in its genre and medium does ___________ resemble?

- How does ___________ distinguish itself from other texts in its genre and medium?

Self-Context Questions

- How have I developed my aesthetic sensibility (my tastes, my likes, and my dislikes)?

- How do I typically respond to absolutes or ambiguities in life or in art? Do I respond favorably to gray areas or do I like things more clear-cut?

- With what groups (ethnic, racial, religious, social, gendered, economic, nationalist, regional, etc.) do I identify?

- How have my social, political, and ethical opinions been formed?

- How do my attitudes toward the “great questions” (choice vs. necessity, nature vs. nurture, tradition vs. change, etc.) affect the way I look at the world?

Self-Text-Context Questions

- How does my personal, cultural, and social background affect my understanding of ________?

- What else might I need to learn about the culture, the historical moment, or the creator that produced ___________ in order to more fully understand it?

- What else about the genre or medium of ___________ might I need to learn in order to understand it better?

- How might ___________ look or sound different if it were produced in a different time or place?

- How might ___________ look or sound different if I were viewing it from a different perspective or identification?

We’ve been told there’s no such thing as a stupid question, but to call certain questions “productive” is to suggest that there’s such a thing as an unproductive question. When you ask rhetorical questions to which you already know the answer or that you expect your audience to answer in a certain way, are you questioning productively? Perhaps not, in the sense of knowledge creation, but you may still be accomplishing a rhetorical purpose. And sometimes even rhetorical questions can produce knowledge. Let’s say you ask your sister, “How can someone as intelligent as you are do such self-destructive things?” Maybe you’re merely trying to direct your sister’s attention to her self-destructive behavior, but upon reflection, the question could actually trigger some productive self-examination on her part.

Hypothetical questions, at first glance, might also seem unproductive since they are usually founded on something that hasn’t happened yet and may never happen. Politicians and debaters try to steer clear of answering them but often ask them of their opponents for rhetorical effect. If we think of hypothetical questions merely as speculative ploys, we may discount their productive possibilities. But hypothetical questions asked in good faith are crucial building blocks of knowledge creation. Asking “What if we tried something else?” leads to the formation of a hypothesis, which is a theory or proposition that can be subjected to testing and experimentation.

This section has focused more on the types of genuinely interrogative questions that can lead to productive ideas for further exploration, research, and knowledge creation once you decide how you want to go public with your thinking.

Key Takeaways

- At least two out of the following three elements are involved in critical inquiry: self, text, and context. When all three are involved, the richest questions arise.

- Expanding your notion of what constitutes a “text” will greatly enrich your possibilities for analysis and interpretation.

- Rhetorical or hypothetical questions, while often used in the public realm, can also perform a useful function in private, low-stakes writing, especially when they are genuinely interrogative and lead to further productive thinking.

Exercises

-

Use the Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context to develop a researched essay topic on one of the following types of texts. Note that you are developing a topic at this point. Sketch out a plan for how you would go about finding answers to some of the questions requiring research.

- An editorial in the newspaper

- A website

- A blog

- A television show

- A music CD or video

- A film

- A video game

- A political candidate

- A building

- A painting or sculpture

- A feature of your college campus

- A short story or poem

- Perform a scavenger hunt in the world of advertising, politics, and/or education for the next week or so to compile a list of questions. (You could draw from the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader” to find examples.) Label each question you find as rhetorical, hypothetical, or interrogative. If the questions are rhetorical or hypothetical, indicate whether they are still being asked in a genuinely interrogative way. Bring your examples to class for discussion or post them to your group’s or class’s discussion board.

- Apply the Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context to a key concept in an introductory course in which you are currently enrolled.

1.3 Slowing Down Your Thinking

Learning Objectives

- Learn the benefits of thinking more slowly.

- Learn the benefits of thinking of the world in smaller chunks.

- Apply slower, more “small-bore” thinking to a piece of student writing.

Given the fast pace of today’s multitasking world, you might wonder why anyone would want to slow down their thinking. Who has that kind of time? The truth is that college will probably present you with more of an opportunity to slow down your thinking than any other time of your adult life. Slowing down your thinking doesn’t mean taking it easy or doing less thinking in the same amount of time. On the contrary, learning to think more slowly is a precondition to making a successful, meaningful contribution to any discipline. The key is to adjust your perspective toward the world around you by seeing it in much smaller chunks.

When you get a writing assignment in a broad topic area asking for a certain number of words or pages (let’s say 1,000 to 1,250 words, or 4 to 5 double-spaced pages, with 12-point font and 1-inch margins), what’s your first reaction? If you’re like most students, you might panic at first, wondering how you’re going to produce that much writing. The irony is that if you try to approach the topic from a perspective that is too general, what you write will likely be as painful to read as it is to write, especially if it’s part of a stack of similarly bland essays. It will inevitably be shallow because a thousand words on ten ideas works out to about a hundred words per idea. But if you slow down your thinking to find a single aspect of the larger topic and devote your thousand words to that single aspect, you’ll be able to approach it from ten different angles, and your essay will distinguish itself from the pack.

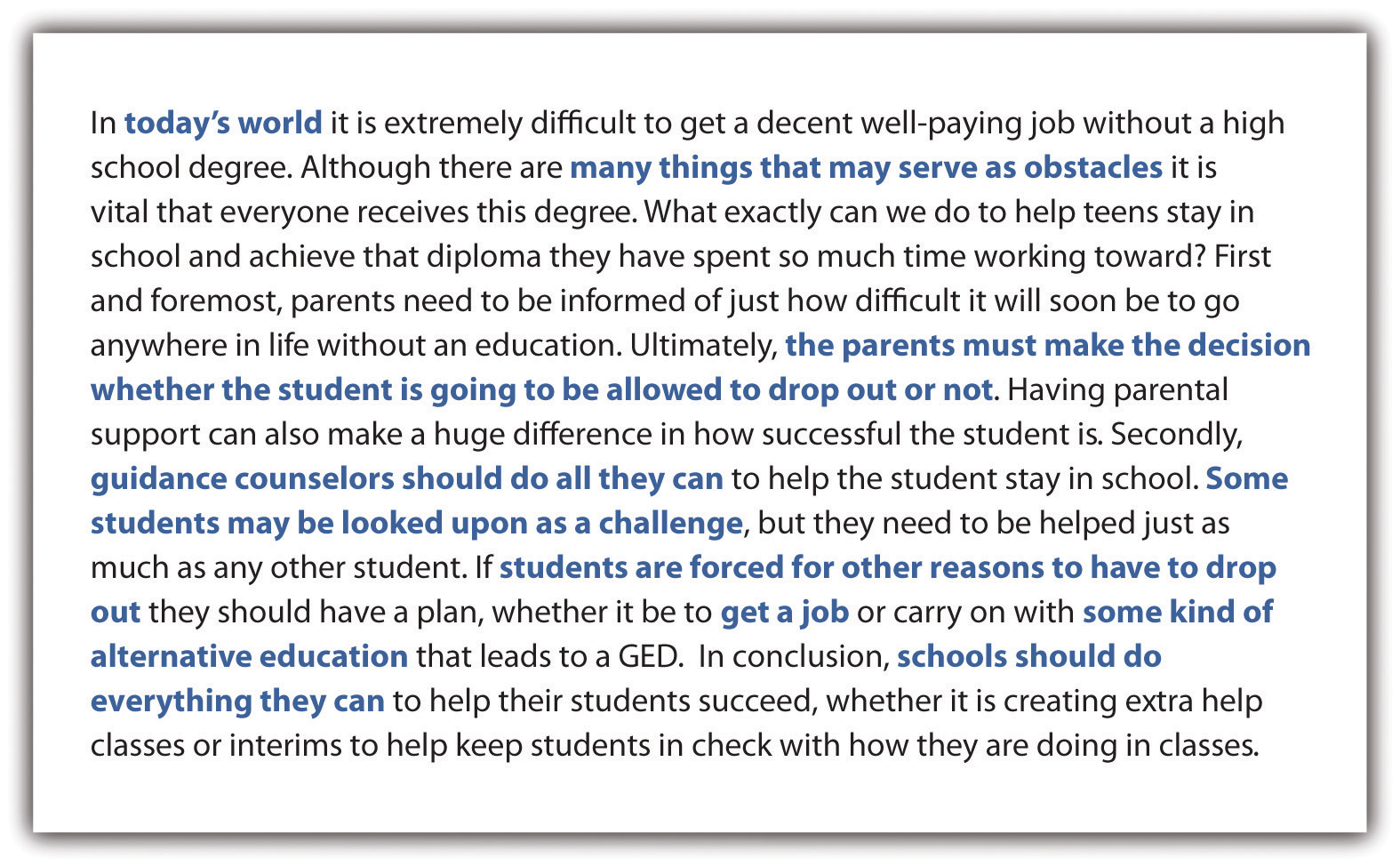

Let’s try this with an excerpt of student writing on high school dropouts that was conducted at warp speed. Either the writer was eager to complete the assignment or she hurried to a conclusion without examining the elements of her topic that she was taking for granted. Every sentence or phrase that could benefit from slower thinking in smaller chunks is set in bold blue font.

This example is not given to find fault with the student’s approach, however rushed it might have been. Each of the bold blue passages is not technically a mistake, but rather a missed opportunity to take a deeper, more methodical approach to a complicated problem. From this one paragraph, one could imagine as many as eight completely researched, full-length essays emerging on the following topics.

| Missed Opportunity | Possible Essay Topic |

|---|---|

| “Today’s world” | A historical comparison with other job markets for high school dropouts |

| “Many things that may serve as an obstacle” or “students are forced for other reasons to have to drop out” | A study of the leading causes of the high school dropout rate |

| “The parents must make the decision whether the student is going to be allowed to drop out or not” | A study of the dynamics of parent-teen relationships in households where the teen is at risk academically |

| “Guidance counselors should do all they can” | An analysis of current practices of allocating guidance counseling to a wide range of high school students |

| “Some students may be looked upon as a challenge” | A profile of the most prominent characteristics of high school students who are at risk academically |

| “Get a job” | A survey of employment opportunities for high school dropouts |

| “Some kind of alternative education” | An evaluation of the current GED (General Educational Development) system |

| “Schools should do everything they can” | A survey of best practices at high schools across the country that have substantially reduced the dropout rate |

The questions you’ve encountered so far in this chapter have been designed to encourage mindfulness, the habit of taking nothing for granted about the text under examination. Even (or especially) when “the text under examination” happens to be your own, you can apply that same habit. The question “What is it I am taking for granted about ____________?” has several variants:

- What am I not asking about _____________ that I should be asking?

- What is it in _____________ that is not being said?

- Is there something in ____________ that “goes without saying” that nonetheless should be said?

- Do I feel like asking a question when I look at ___________ even though it’s telling me not to?

Slowing down your thinking isn’t an invitation to sit on the sidelines. If anything, you should be in a better position to make a real contribution once you’ve learned to focus your communication skills on a precise area of most importance to you.

Key Takeaways

- Even in a world of high-speed multitasking, thinking deliberately about small, specific things can pay great academic and professional dividends.

- Disciplines and professions rely on many participants thinking and writing about many small-bore topics over an extended period of time.

- Practically any text, especially an early piece of your writing or that of a classmate, can benefit from at least one variation on the question, “What is it I am taking for granted?”

Exercises

- Take a piece of your writing from a previous class or another class you are currently taking, or even from this class, and subject it to a thorough scouring for phrases and sentences that exhibit rushed thinking. Set up a chart similar to the one that appears in this section, listing every missed opportunity and every possible essay topic that emerges from the text once your thinking is slowed down.

- Now try this same exercise on a classmate’s piece of writing, and offer up one of your own for them to work on.

-

Sometimes texts demonstrate thinking that is sped up or oversimplified on purpose, as a method of misleading readers. Find an example of a text that’s inviting readers or listeners to take something for granted or to think too quickly. (You might look in the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader” to find examples.) Subject the example you find to the questions in this section. Bring the example and your analysis of it to class for discussion or include both the example and your analysis in your group’s or class’s discussion board. Choose from among one of the following categories or come up with a category of your own:

- An editorial column

- A bumper sticker

- A billboard

- A banner on a website

- A political slogan or speech

- A financial, educational, or occupational document

- A song lyric

- A movie or television show plotline

- A commercial advertisement

- A message from a friend or family member

1.4 Withholding Judgment

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the value, power, and authority derived from paying attention to detail before moving on to evaluative judgment.

- Consider the danger of a judgment reached prematurely.

- Investigate the cultural and educational forces that may have encouraged you to rush to judgment.

We live in a culture that values taking a stance, having an opinion, making a judgment, and backing it up with evidence. Being undecided or even open-minded about an issue can be seen as a sign of weakness or sloppiness or even as a moral or ethical failing. Our culture also privileges action over the kind of reflection and contemplation this chapter is advocating.

If you’ve encountered mostly traditional writing instruction, you’ve probably been encouraged to make judgments fairly early in the writing process. Well before you have fully examined an issue, you’ve been told to “take a position and defend it.” You might make an effort to understand an issue from multiple sides (a process discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 “Thinking through the Disciplines”, Section 3.2 “Seeing and Making Connections across Disciplines” and Chapter 3 “Thinking through the Disciplines”, Section 3.3 “Articulating Multiple Sides of an Issue”) only after you have staked your claim in a half-hearted effort to be “fair to both sides.”

If you’ve been subjected to standardized tests of writing ability (often key factors in decisions about college acceptance and placement and earlier, in assessments of competence at various levels of K–12 education), you’ve probably noticed they rely on essay prompts that put heavy emphasis on argumentation. Some evaluative rubrics for such essays require the presence of a thesis statement by the end of the introductory paragraph in order to earn a high score for organization.

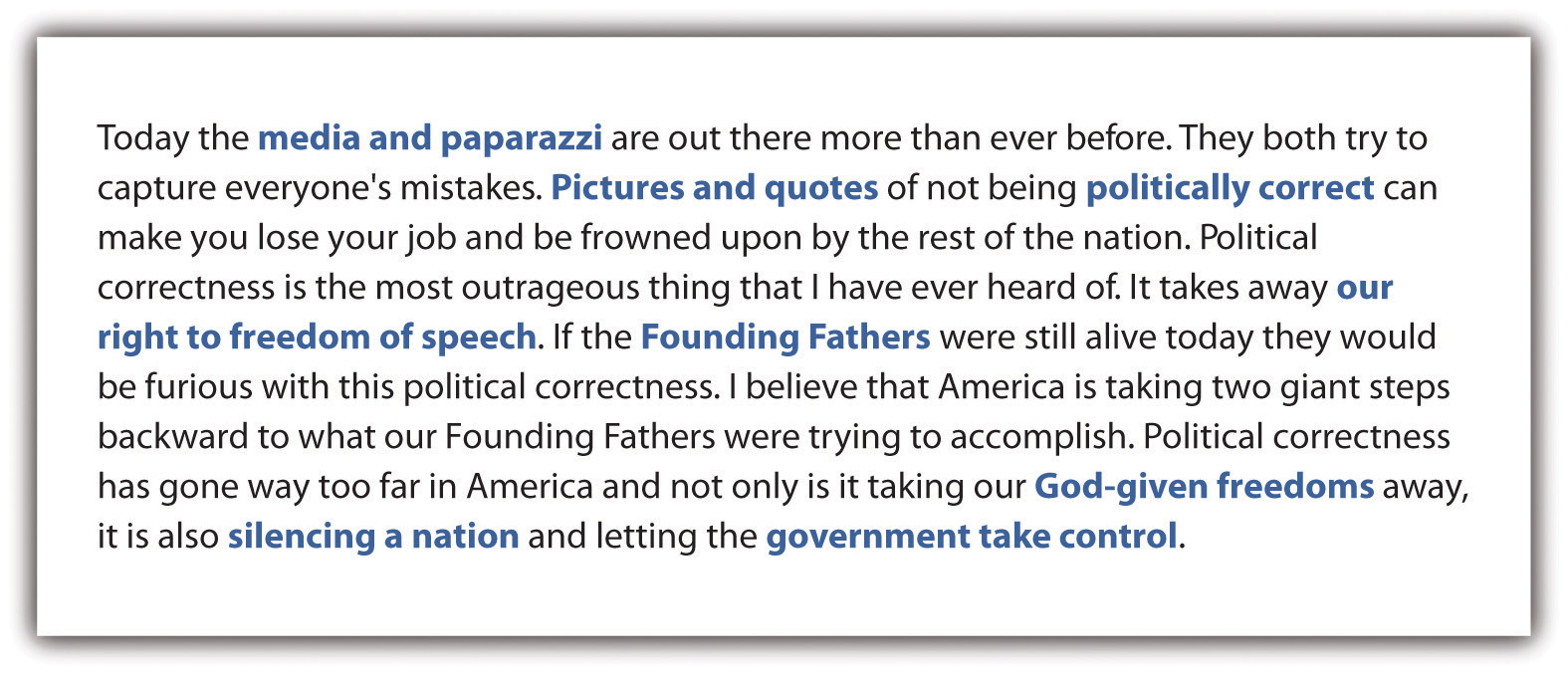

Here’s an introductory paragraph of a student writer who has been trained by the “point–counterpoint” culture of sound bites and perhaps encouraged by writing teachers over the years to believe that he has very little time to get to his thesis statement.

The rush to judgment has caused this student to fall into the same quick-thinking trap of the student in Section 1.3 “Slowing Down Your Thinking”. The remedy (isolating the phrases worthy of further examination, indicated here, as in Section 1.3 “Slowing Down Your Thinking”, with bold blue font) is similar. This student may yet make something useful out of his concerns about political correctness, but he will do so only by making a meaningful effort to withhold his judgment on what is actually a much more complicated issue.

| Premature Judgment | Complicating Question |

|---|---|

| “Media and paparazzi” | What is the press’s motivation for insisting on political correctness? |

| “Pictures and quotes” | What examples can I find as test cases for analysis? |

| “Politically correct” | What is the definition and the history of this phrase? |

| “Our right to freedom of speech” | How does political correctness run counter to the First Amendment’s protection of speech? |

| “Founding fathers” | Did the founders debate matters of press freedom and appropriate speech? |

| “God-given freedoms” | What are the intersections between religion and the right to free speech? |

| “Silencing a nation” | Are there sensitive subjects we don’t address as a nation because of political correctness? |

| “Government takes control” | How might a government create an atmosphere of political correctness in order to control its people? |

Much of the pressure to reach judgments prematurely comes from elements of society that do not necessarily have our best interests in mind. The last exercise of Section 1.3 “Slowing Down Your Thinking” hinted at the strategic reasons why corporations, politicians, ideologues, popular entertainers, authority figures, or even friends and family might try to speed up your thinking at precisely the moment when you should be slowing it down. While inaction and dithering can be cited as the cause of some of history’s worst moments, the “rush to judgment” that comes from rash thinking can be cited as the cause of many more. A good rule of thumb when you are asked to make an irrevocable judgment or decision is to ask yourself or your questioner, “What’s your hurry?”

Key Takeaways

- Our sound-bite, point–counterpoint culture and even our reductive definitions of effective writing place a heavy emphasis on taking a position early and sticking to it.

- One must eventually take action after a period of contemplation, but history is full of examples of judgments made in haste.

- Withholding judgment, like slowing down your thinking, can be an effective strategy for revision and peer review.

Exercises

- Take a piece of your writing from a previous class or another class you are currently taking, or even from this class, and look for phrases and sentences that suggest a “rush to judgment.” Set up a chart similar to the one that appears in this section, listing every possible essay topic that emerges from the complicating questions you write in response to each premature judgment.

- Now try this same exercise on a classmate’s piece of writing and offer up one of your own for him or her to work on.

-

Compare the pace with which a writer makes a judgment in the each of the following rhetorical settings. Discuss whether you think there are certain conventions about making, presenting, and defending judgments in each of these genres. Draw from the Note 2.5 “Gallery of Web-Based Texts” in Chapter 2 “Becoming a Critical Reader” to find examples.

- A television commercial for a political candidate, a pharmaceutical company, or an investment firm

- A Supreme Court majority opinion

- A presidential address on a topic of national security

- A journal article in a field you are studying

Candela Citations

- Writing to Think and Writing to Learn. Authored by: Withheld by Lardbucket at Publishers' Request (see https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/writers-handbook/). Provided by: Lardbucket. Located at: https://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/writers-handbook/. Project: Writers' Handbook. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike