Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify U.S. budget deficit and surplus trends over the past five decades

- Explain the differences between the U.S. federal budget, and state and local budgets

Government spending covers a range of services that the federal, state, and local governments provide. When the federal government spends more money than it receives in taxes in a given year, it runs a budget deficit. Conversely, when the government receives more money in taxes than it spends in a year, it runs a budget surplus. If government spending and taxes are equal, it has a balanced budget. For example, in 2009, the U.S. government experienced its largest budget deficit ever, as the federal government spent $1.4 trillion more than it collected in taxes. This deficit was about 10% of the size of the U.S. GDP in 2009, making it by far the largest budget deficit relative to GDP since the mammoth borrowing the government used to finance World War II.

This section presents an overview of government spending in the United States.

Total U.S. Government Spending

Federal spending in nominal dollars (that is, dollars not adjusted for inflation) has grown by a multiple of more than 38 over the last four decades, from $93.4 billion in 1960 to $3.9 trillion in 2014. Comparing spending over time in nominal dollars is misleading because it does not take into account inflation or growth in population and the real economy. A more useful method of comparison is to examine government spending as a percent of GDP over time.

The top line in [link] shows the federal spending level since 1960, expressed as a share of GDP. Despite a widespread sense among many Americans that the federal government has been growing steadily larger, the graph shows that federal spending has hovered in a range from 18% to 22% of GDP most of the time since 1960. The other lines in [link] show the major federal spending categories: national defense, Social Security, health programs, and interest payments. From the graph, we see that national defense spending as a share of GDP has generally declined since the 1960s, although there were some upward bumps in the 1980s buildup under President Ronald Reagan and in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. In contrast, Social Security and healthcare have grown steadily as a percent of GDP. Healthcare expenditures include both payments for senior citizens (Medicare), and payments for low-income Americans (Medicaid). State governments also partially fund Medicaid. Interest payments are the final main category of government spending in Figure 30.2.

Federal Spending, 1960–2014. Since 1960, total federal spending has ranged from about 18% to 22% of GDP, although it climbed above that level in 2009, but quickly dropped back down to that level by 2013. The share that the government has spent on national defense has generally declined, while the share it has spent on Social Security and on healthcare expenses (mainly Medicare and Medicaid) has increased. (Source: Economic Report of the President, Tables B-2 and B-22, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/ERP-2014/content-detail.html)

Each year, the government borrows funds from U.S. citizens and foreigners to cover its budget deficits. It does this by selling securities (Treasury bonds, notes, and bills)—in essence borrowing from the public and promising to repay with interest in the future. From 1961 to 1997, the U.S. government has run budget deficits, and thus borrowed funds, in almost every year. It had budget surpluses from 1998 to 2001, and then returned to deficits.

The interest payments on past federal government borrowing were typically 1–2% of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s but then climbed above 3% of GDP in the 1980s and stayed there until the late 1990s. The government was able to repay some of its past borrowing by running surpluses from 1998 to 2001 and, with help from low interest rates, the interest payments on past federal government borrowing had fallen back to 1.4% of GDP by 2012.

We investigate the government borrowing and debt patterns in more detail later in this chapter, but first we need to clarify the difference between the deficit and the debt. The deficit is not the debt. The difference between the deficit and the debt lies in the time frame. The government deficit (or surplus) refers to what happens with the federal government budget each year. The government debt is accumulated over time. It is the sum of all past deficits and surpluses. If you borrow $10,000 per year for each of the four years of college, you might say that your annual deficit was $10,000, but your accumulated debt over the four years is $40,000.

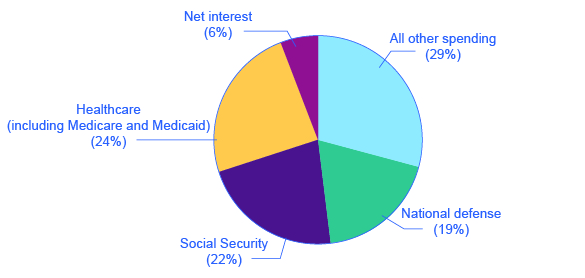

These four categories—national defense, Social Security, healthcare, and interest payments—account for roughly 73% of all federal spending, as [link] shows. The remaining 27% wedge of the pie chart covers all other categories of federal government spending: international affairs; science and technology; natural resources and the environment; transportation; housing; education; income support for the poor; community and regional development; law enforcement and the judicial system; and the administrative costs of running the government.

Slices of Federal Spending, 2014. About 73% of government spending goes to four major areas: national defense, Social Security, healthcare, and interest payments on past borrowing. This leaves about 29% of federal spending for all other functions of the U.S. government. (Source: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals/)

State and Local Government Spending

Although federal government spending often gets most of the media attention, state and local government spending is also substantial—at about $3.1 trillion in 2014. [link] shows that state and local government spending has increased during the last four decades from around 8% to around 14% today. The single biggest item is education, which accounts for about one-third of the total. The rest covers programs like highways, libraries, hospitals and healthcare, parks, and police and fire protection. Unlike the federal government, all states (except Vermont) have balanced budget laws, which means any gaps between revenues and spending must be closed by higher taxes, lower spending, drawing down their previous savings, or some combination of all of these.

State and Local Spending, 1960–2013. Spending by state and local government increased from about 10% of GDP in the early 1960s to 14–16% by the mid-1970s. It has remained at roughly that level since. The single biggest spending item is education, including both K–12 spending and support for public colleges and universities, which has been about 4–5% of GDP in recent decades. Source: (Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.)

U.S. presidential candidates often run for office pledging to improve the public schools or to get tough on crime. However, in the U.S. government system, these tasks are primarily state and local government responsibilities. In fiscal year 2014 state and local governments spent about $840 billion per year on education (including K–12 and college and university education), compared to only $100 billion by the federal government, according to usgovernmentspending.com. In other words, about 90 cents of every dollar spent on education happens at the state and local level. A politician who really wants hands-on responsibility for reforming education or reducing crime might do better to run for mayor of a large city or for state governor rather than for president of the United States.

Key Concepts and Summary

Fiscal policy is the set of policies that relate to federal government spending, taxation, and borrowing. In recent decades, the level of federal government spending and taxes, expressed as a share of GDP, has not changed much, typically fluctuating between about 18% to 22% of GDP. However, the level of state spending and taxes, as a share of GDP, has risen from about 12–13% to about 20% of GDP over the last four decades. The four main areas of federal spending are national defense, Social Security, healthcare, and interest payments, which together account for about 70% of all federal spending. When a government spends more than it collects in taxes, it is said to have a budget deficit. When a government collects more in taxes than it spends, it is said to have a budget surplus. If government spending and taxes are equal, it is said to have a balanced budget. The sum of all past deficits and surpluses make up the government debt.

Self-Check Questions

When governments run budget deficits, how do they make up the differences between tax revenue and spending?

The government borrows funds by selling Treasury bonds, notes, and bills.

When governments run budget surpluses, what is done with the extra funds?

The funds can be used to pay down the national debt or else be refunded to the taxpayers.

Is it possible for a nation to run budget deficits and still have its debt/GDP ratio fall? Explain your answer. Is it possible for a nation to run budget surpluses and still have its debt/GDP ratio rise? Explain your answer.

Yes, a nation can run budget deficits and see its debt/GDP ratio fall. In fact, this is not uncommon. If the deficit is small in a given year, than the addition to debt in the numerator of the debt/GDP ratio will be relatively small, while the growth in GDP is larger, and so the debt/GDP ratio declines. This was the experience of the U.S. economy for the period from the end of World War II to about 1980. It is also theoretically possible, although not likely, for a nation to have a budget surplus and see its debt/GDP ratio rise. Imagine the case of a nation with a small surplus, but in a recession year when the economy shrinks. It is possible that the decline in the nation’s debt, in the numerator of the debt/GDP ratio, would be proportionally less than the fall in the size of GDP, so the debt/GDP ratio would rise.

Review Questions

Give some examples of changes in federal spending and taxes by the government that would be fiscal policy and some that would not.

Have the spending and taxes of the U.S. federal government generally had an upward or a downward trend in the last few decades?

What are the main categories of U.S. federal government spending?

What is the difference between a budget deficit, a balanced budget, and a budget surplus?

Have spending and taxes by state and local governments in the United States had a generally upward or downward trend in the last few decades?

Critical Thinking Questions

Why is government spending typically measured as a percentage of GDP rather than in nominal dollars?

Why are expenditures such as crime prevention and education typically done at the state and local level rather than at the federal level?

Why is spending by the U.S. government on scientific research at NASA fiscal policy while spending by the University of Illinois is not fiscal policy? Why is a cut in the payroll tax fiscal policy whereas a cut in a state income tax is not fiscal policy?

Problems

A government starts off with a total debt of $3.5 billion. In year one, the government runs a deficit of $400 million. In year two, the government runs a deficit of $1 billion. In year three, the government runs a surplus of $200 million. What is the total debt of the government at the end of year three?

References

Kramer, Mattea, et. al. A People’s Guide to the Federal Budget. National Priorities Project. Northampton: Interlink Books, 2012.

Kurtzleben, Danielle. “10 States With The Largest Budget Shortfalls.” U.S. News & World Report. Januray 14, 2011. http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2011/01/14/10-states-with-the-largest-budget-shortfalls.

Miller, Rich, and William Selway. “U.S. Cities and States Start Spending Again.” BloombergBusinessweek, January 10, 2013. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2013-01-10/u-dot-s-dot-cities-and-states-start-spending-again.

Weisman, Jonathan. “After Year of Working Around Federal Cuts, Agencies Face Fewer Options.” The New York Times, October 26, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/27/us/politics/after-year-of-working-around-federal-cuts-agencies-face-fewer-options.html?_r=0.

Chantrill, Christopher. USGovernmentSpending.com. “Government Spending Details: United States Federal State and Local Government Spending, Fiscal Year 2013.” http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/year_spending_2013USbn_15bs2n_20.

Glossary

- balanced budget

- when government spending and taxes are equal

- budget deficit

- when the federal government spends more money than it receives in taxes in a given year

- budget surplus

- when the government receives more money in taxes than it spends in a year

Candela Citations

- Principles of Macroeconomics 2e. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/27f59064-990e-48f1-b604-5188b9086c29@5.5. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/27f59064-990e-48f1-b604-5188b9086c29@5.5