Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the arrangement of atoms and ions in crystalline structures

- Compute ionic radii using unit cell dimensions

- Explain the use of X-ray diffraction measurements in determining crystalline structures

Over 90% of naturally occurring and man-made solids are crystalline. Most solids form with a regular arrangement of their particles because the overall attractive interactions between particles are maximized, and the total intermolecular energy is minimized, when the particles pack in the most efficient manner. The regular arrangement at an atomic level is often reflected at a macroscopic level. In this module, we will explore some of the details about the structures of metallic and ionic crystalline solids, and learn how these structures are determined experimentally.

The Structures of Metals

We will begin our discussion of crystalline solids by considering elemental metals, which are relatively simple because each contains only one type of atom. A pure metal is a crystalline solid with metal atoms packed closely together in a repeating pattern. Some of the properties of metals in general, such as their malleability and ductility, are largely due to having identical atoms arranged in a regular pattern. The different properties of one metal compared to another partially depend on the sizes of their atoms and the specifics of their spatial arrangements. We will explore the similarities and differences of four of the most common metal crystal geometries in the sections that follow.

Unit Cells of Metals

The structure of a crystalline solid, whether a metal or not, is best described by considering its simplest repeating unit, which is referred to as its unit cell. The unit cell consists of lattice points that represent the locations of atoms or ions. The entire structure then consists of this unit cell repeating in three dimensions, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A unit cell shows the locations of lattice points repeating in all directions.

Let us begin our investigation of crystal lattice structure and unit cells with the most straightforward structure and the most basic unit cell. To visualize this, imagine taking a large number of identical spheres, such as tennis balls, and arranging them uniformly in a container. The simplest way to do this would be to make layers in which the spheres in one layer are directly above those in the layer below, as illustrated in Figure 2. This arrangement is called simple cubic structure, and the unit cell is called the simple cubic unit cell or primitive cubic unit cell.

Figure 2. When metal atoms are arranged with spheres in one layer directly above or below spheres in another layer, the lattice structure is called simple cubic. Note that the spheres are in contact.

In a simple cubic structure, the spheres are not packed as closely as they could be, and they only “fill” about 52% of the volume of the container. This is a relatively inefficient arrangement, and only one metal (polonium, Po) crystallizes in a simple cubic structure. As shown in Figure 3, a solid with this type of arrangement consists of planes (or layers) in which each atom contacts only the four nearest neighbors in its layer; one atom directly above it in the layer above; and one atom directly below it in the layer below. The number of other particles that each particle in a crystalline solid contacts is known as its coordination number. For a polonium atom in a simple cubic array, the coordination number is, therefore, six.

Figure 3. An atom in a simple cubic lattice structure contacts six other atoms, so it has a coordination number of six.

In a simple cubic lattice, the unit cell that repeats in all directions is a cube defined by the centers of eight atoms, as shown in Figure 4. Atoms at adjacent corners of this unit cell contact each other, so the edge length of this cell is equal to two atomic radii, or one atomic diameter. A cubic unit cell contains only the parts of these atoms that are within it. Since an atom at a corner of a simple cubic unit cell is contained by a total of eight unit cells, only one-eighth of that atom is within a specific unit cell. And since each simple cubic unit cell has one atom at each of its eight “corners,” there is [latex]8 \times \frac{1}{8}=1[/latex] atom within one simple cubic unit cell.

Figure 4. A simple cubic lattice unit cell contains one-eighth of an atom at each of its eight corners, so it contains one atom total.

Example 1: Calculation of Atomic Radius and Density for Metals, Part 1

The edge length of the unit cell of alpha polonium is 336 pm.

- Determine the radius of a polonium atom.

- Determine the density of alpha polonium.

Check Your Learning

The edge length of the unit cell for nickel is 0.3524 nm. The density of Ni is 8.90 g/cm3. Does nickel crystallize in a simple cubic structure? Explain.

Most metal crystals are one of the four major types of unit cells. For now, we will focus on the three cubic unit cells: simple cubic (which we have already seen), body-centered cubic unit cell, and face-centered cubic unit cell—all of which are illustrated in Figure 5. (Note that there are actually seven different lattice systems, some of which have more than one type of lattice, for a total of 14 different types of unit cells. We leave the more complicated geometries for later in this module.)

Figure 5. Cubic unit cells of metals show (in the upper figures) the locations of lattice points and (in the lower figures) metal atoms located in the unit cell.

Some metals crystallize in an arrangement that has a cubic unit cell with atoms at all of the corners and an atom in the center, as shown in Figure 6. This is called a body-centered cubic (BCC) solid. Atoms in the corners of a BCC unit cell do not contact each other but contact the atom in the center. A BCC unit cell contains two atoms: one-eighth of an atom at each of the eight corners ( [latex]8\times \frac{1}{8}=1[/latex] atom from the corners) plus one atom from the center. Any atom in this structure touches four atoms in the layer above it and four atoms in the layer below it. Thus, an atom in a BCC structure has a coordination number of eight.

Figure 6. In a body-centered cubic structure, atoms in a specific layer do not touch each other. Each atom touches four atoms in the layer above it and four atoms in the layer below it.

Atoms in BCC arrangements are much more efficiently packed than in a simple cubic structure, occupying about 68% of the total volume. Isomorphous metals with a BCC structure include K, Ba, Cr, Mo, W, and Fe at room temperature. (Elements or compounds that crystallize with the same structure are said to be isomorphous.)

Many other metals, such as aluminum, copper, and lead, crystallize in an arrangement that has a cubic unit cell with atoms at all of the corners and at the centers of each face, as illustrated in Figure 7. This arrangement is called a face-centered cubic (FCC) solid. A FCC unit cell contains four atoms: one-eighth of an atom at each of the eight corners ( [latex]8\times \frac{1}{8}=1[/latex] atom from the corners) and one-half of an atom on each of the six faces ([latex]6\times \frac{1}{2}=3[/latex] atoms from the faces). The atoms at the corners touch the atoms in the centers of the adjacent faces along the face diagonals of the cube. Because the atoms are on identical lattice points, they have identical environments.

Figure 7. A face-centered cubic solid has atoms at the corners and, as the name implies, at the centers of the faces of its unit cells.

Atoms in an FCC arrangement are packed as closely together as possible, with atoms occupying 74% of the volume. This structure is also called cubic closest packing (CCP). In CCP, there are three repeating layers of hexagonally arranged atoms. Each atom contacts six atoms in its own layer, three in the layer above, and three in the layer below. In this arrangement, each atom touches 12 near neighbors, and therefore has a coordination number of 12. The fact that FCC and CCP arrangements are equivalent may not be immediately obvious, but why they are actually the same structure is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8. A CCP arrangement consists of three repeating layers (ABCABC…) of hexagonally arranged atoms. Atoms in a CCP structure have a coordination number of 12 because they contact six atoms in their layer, plus three atoms in the layer above and three atoms in the layer below. By rotating our perspective, we can see that a CCP structure has a unit cell with a face containing an atom from layer A at one corner, atoms from layer B across a diagonal (at two corners and in the middle of the face), and an atom from layer C at the remaining corner. This is the same as a face-centered cubic arrangement.

Because closer packing maximizes the overall attractions between atoms and minimizes the total intermolecular energy, the atoms in most metals pack in this manner. We find two types of closest packing in simple metallic crystalline structures: CCP, which we have already encountered, and hexagonal closest packing (HCP) shown in Figure 9. Both consist of repeating layers of hexagonally arranged atoms. In both types, a second layer (B) is placed on the first layer (A) so that each atom in the second layer is in contact with three atoms in the first layer. The third layer is positioned in one of two ways. In HCP, atoms in the third layer are directly above atoms in the first layer (i.e., the third layer is also type A), and the stacking consists of alternating type A and type B close-packed layers (i.e., ABABAB⋯). In CCP, atoms in the third layer are not above atoms in either of the first two layers (i.e., the third layer is type C), and the stacking consists of alternating type A, type B, and type C close-packed layers (i.e., ABCABCABC⋯). About two–thirds of all metals crystallize in closest-packed arrays with coordination numbers of 12. Metals that crystallize in an HCP structure include Cd, Co, Li, Mg, Na, and Zn, and metals that crystallize in a CCP structure include Ag, Al, Ca, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Pt.

Figure 9. In both types of closest packing, atoms are packed as compactly as possible. Hexagonal closest packing consists of two alternating layers (ABABAB…). Cubic closest packing consists of three alternating layers (ABCABCABC…).

Example 2: Calculation of Atomic Radius and Density for Metals, Part 2

Calcium crystallizes in a face-centered cubic structure. The edge length of its unit cell is 558.8 pm.

- What is the atomic radius of Ca in this structure?

- Calculate the density of Ca.

Check Your Learning

Silver crystallizes in an FCC structure. The edge length of its unit cell is 409 pm.

- What is the atomic radius of Ag in this structure?

- Calculate the density of Ag.

In general, a unit cell is defined by the lengths of three axes (a, b, and c) and the angles (α, β, and γ) between them, as illustrated in Figure 11. The axes are defined as being the lengths between points in the space lattice. Consequently, unit cell axes join points with identical environments.

Figure 11. A unit cell is defined by the lengths of its three axes (a, b, and c) and the angles (α, β, and γ) between the axes.

There are seven different lattice systems, some of which have more than one type of lattice, for a total of fourteen different unit cells, which have the shapes shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. There are seven different lattice systems and 14 different unit cells.

Unit Cells of Ionic Compounds

Many ionic compounds crystallize with cubic unit cells, and we will use these compounds to describe the general features of ionic structures.

When an ionic compound is composed of cations and anions of similar size in a 1:1 ratio, it typically forms a simple cubic structure. Cesium chloride, CsCl, (illustrated in Figure 13) is an example of this, with Cs+ and Cl− having radii of 174 pm and 181 pm, respectively. We can think of this as chloride ions forming a simple cubic unit cell, with a cesium ion in the center; or as cesium ions forming a unit cell with a chloride ion in the center; or as simple cubic unit cells formed by Cs+ ions overlapping unit cells formed by Cl− ions. Cesium ions and chloride ions touch along the body diagonals of the unit cells. One cesium ion and one chloride ion are present per unit cell, giving the l:l stoichiometry required by the formula for cesium chloride. Note that there is no lattice point in the center of the cell, and CsCl is not a BCC structure because a cesium ion is not identical to a chloride ion.

Figure 13. Ionic compounds with similar-sized cations and anions, such as CsCl, usually form a simple cubic structure. They can be described by unit cells with either cations at the corners or anions at the corners.

We have said that the location of lattice points is arbitrary. This is illustrated by an alternate description of the CsCl structure in which the lattice points are located in the centers of the cesium ions. In this description, the cesium ions are located on the lattice points at the corners of the cell, and the chloride ion is located at the center of the cell. The two unit cells are different, but they describe identical structures.

When an ionic compound is composed of a 1:1 ratio of cations and anions that differ significantly in size, it typically crystallizes with an FCC unit cell, like that shown in Figure 14. Sodium chloride, NaCl, is an example of this, with Na+ and Cl− having radii of 102 pm and 181 pm, respectively. We can think of this as chloride ions forming an FCC cell, with sodium ions located in the octahedral holes in the middle of the cell edges and in the center of the cell. The sodium and chloride ions touch each other along the cell edges. The unit cell contains four sodium ions and four chloride ions, giving the 1:1 stoichiometry required by the formula, NaCl.

Figure 14. Ionic compounds with anions that are much larger than cations, such as NaCl, usually form an FCC structure. They can be described by FCC unit cells with cations in the octahedral holes.

The cubic form of zinc sulfide, zinc blende, also crystallizes in an FCC unit cell, as illustrated in Figure 15. This structure contains sulfide ions on the lattice points of an FCC lattice. (The arrangement of sulfide ions is identical to the arrangement of chloride ions in sodium chloride.) The radius of a zinc ion is only about 40% of the radius of a sulfide ion, so these small Zn2+ ions are located in alternating tetrahedral holes, that is, in one half of the tetrahedral holes. There are four zinc ions and four sulfide ions in the unit cell, giving the empirical formula ZnS.

Figure 15. ZnS, zinc sulfide (or zinc blende) forms an FCC unit cell with sulfide ions at the lattice points and much smaller zinc ions occupying half of the tetrahedral holes in the structure.

A calcium fluoride unit cell, like that shown in Figure 16, is also an FCC unit cell, but in this case, the cations are located on the lattice points; equivalent calcium ions are located on the lattice points of an FCC lattice. All of the tetrahedral sites in the FCC array of calcium ions are occupied by fluoride ions. There are four calcium ions and eight fluoride ions in a unit cell, giving a calcium:fluorine ratio of l:2, as required by the chemical formula, CaF2. Close examination of Figure 17 will reveal a simple cubic array of fluoride ions with calcium ions in one half of the cubic holes. The structure cannot be described in terms of a space lattice of points on the fluoride ions because the fluoride ions do not all have identical environments. The orientation of the four calcium ions about the fluoride ions differs.

Figure 16. Calcium fluoride, CaF2, forms an FCC unit cell with calcium ions (green) at the lattice points and fluoride ions (red) occupying all of the tetrahedral sites between them.

Calculation of Ionic Radii

If we know the edge length of a unit cell of an ionic compound and the position of the ions in the cell, we can calculate ionic radii for the ions in the compound if we make assumptions about individual ionic shapes and contacts.

Example 5: Calculation of Ionic Radii

The edge length of the unit cell of LiCl (NaCl-like structure, FCC) is 0.514 nm or 5.14 Å. Assuming that the lithium ion is small enough so that the chloride ions are in contact, as in Figure 15, calculate the ionic radius for the chloride ion.

Note: The length unit angstrom, Å, is often used to represent atomic-scale dimensions and is equivalent to 10−10 m.

Check Your Learning

The edge length of the unit cell of KCl (NaCl-like structure, FCC) is 6.28 Å. Assuming anion-cation contact along the cell edge, calculate the radius of the potassium ion. The radius of the chloride ion is 1.82 Å.

It is important to realize that values for ionic radii calculated from the edge lengths of unit cells depend on numerous assumptions, such as a perfect spherical shape for ions, which are approximations at best. Hence, such calculated values are themselves approximate and comparisons cannot be pushed too far. Nevertheless, this method has proved useful for calculating ionic radii from experimental measurements such as X-ray crystallographic determinations.

X-Ray Crystallography

The size of the unit cell and the arrangement of atoms in a crystal may be determined from measurements of the diffraction of X-rays by the crystal, termed X-ray crystallography. Diffraction is the change in the direction of travel experienced by an electromagnetic wave when it encounters a physical barrier whose dimensions are comparable to those of the wavelength of the light. X-rays are electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths about as long as the distance between neighboring atoms in crystals (on the order of a few Å).

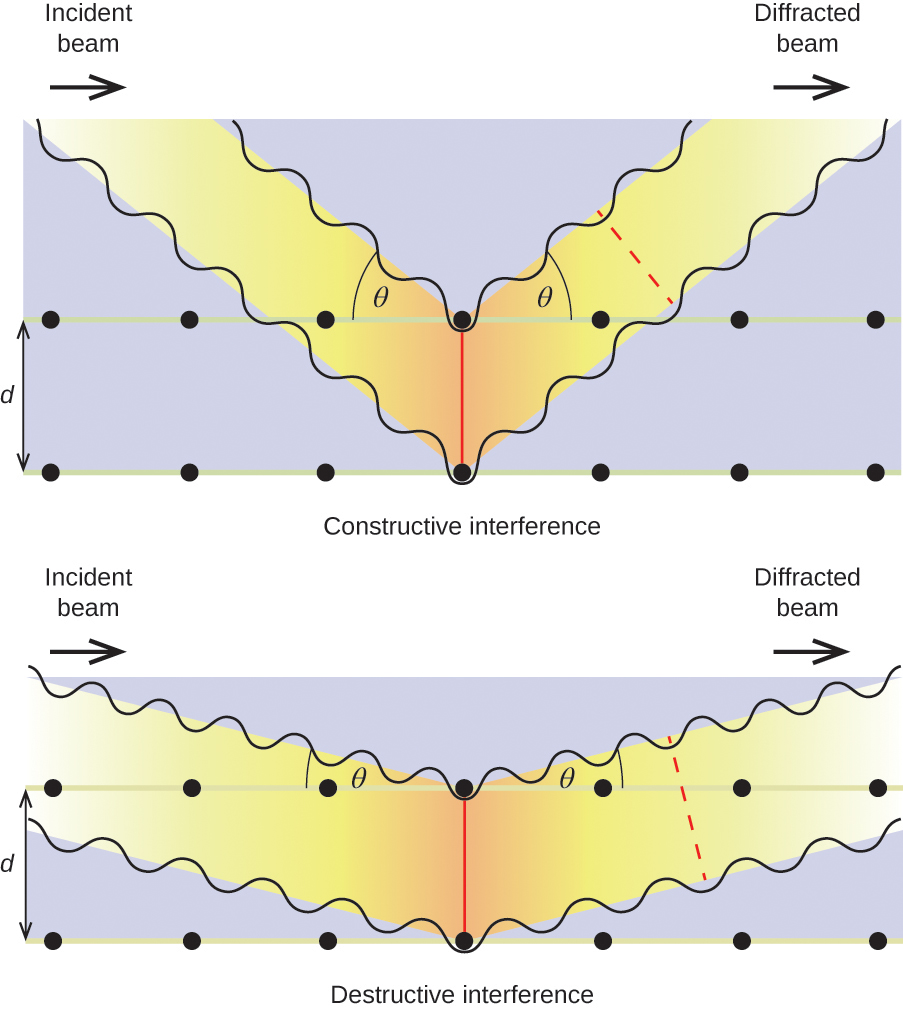

When a beam of monochromatic X-rays strikes a crystal, its rays are scattered in all directions by the atoms within the crystal. When scattered waves traveling in the same direction encounter one another, they undergo interference, a process by which the waves combine to yield either an increase or a decrease in amplitude (intensity) depending upon the extent to which the combining waves’ maxima are separated (see Figure 17).

Figure 17. Light waves occupying the same space experience interference, combining to yield waves of greater (a) or lesser (b) intensity, depending upon the separation of their maxima and minima.

When X-rays of a certain wavelength, λ, are scattered by atoms in adjacent crystal planes separated by a distance, d, they may undergo constructive interference when the difference between the distances traveled by the two waves prior to their combination is an integer factor, n, of the wavelength. This condition is satisfied when the angle of the diffracted beam, θ, is related to the wavelength and interatomic distance by the equation:

[latex]n{\lambda }=2d\text{sin}\theta [/latex]

This relation is known as the Bragg equation in honor of W. H. Bragg, the English physicist who first explained this phenomenon. Figure 18 illustrates two examples of diffracted waves from the same two crystal planes. The figure on the left depicts waves diffracted at the Bragg angle, resulting in constructive interference, while that on the right shows diffraction and a different angle that does not satisfy the Bragg condition, resulting in destructive interference.

Figure 18. The diffraction of X-rays scattered by the atoms within a crystal permits the determination of the distance between the atoms. The top image depicts constructive interference between two scattered waves and a resultant diffracted wave of high intensity. The bottom image depicts destructive interference and a low intensity diffracted wave.

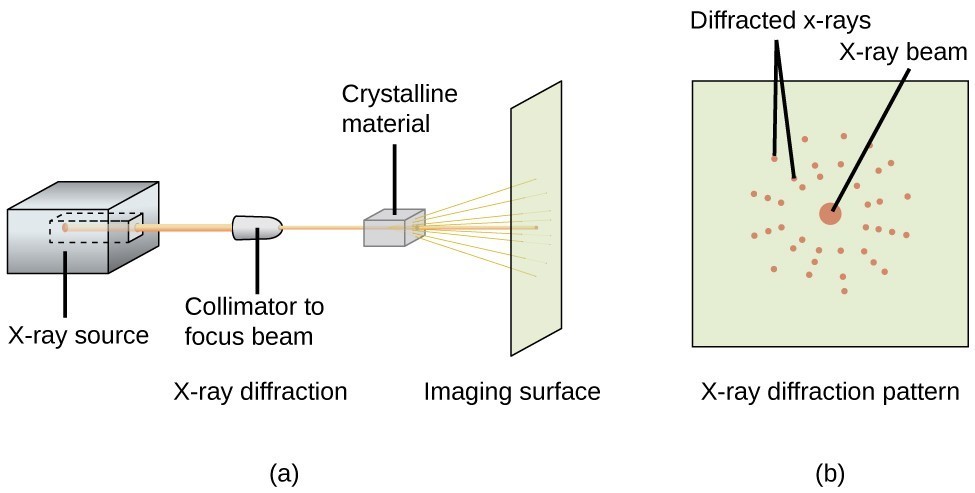

An X-ray diffractometer, such as the one illustrated in Figure 19, may be used to measure the angles at which X-rays are diffracted when interacting with a crystal as described above. From such measurements, the Bragg equation may be used to compute distances between atoms as demonstrated in the following example exercise.

Figure 19. In a diffractometer (a), a beam of X-rays strikes a crystalline material, producing an X-ray diffraction pattern (b) that can be analyzed to determine the crystal structure.

Example 6: Using the Bragg Equation

In a diffractometer, X-rays with a wavelength of 0.1315 nm were used to produce a diffraction pattern for copper. The first order diffraction (n = 1) occurred at an angle θ = 25.25°. Determine the spacing between the diffracting planes in copper.

Check Your Learning

A crystal with spacing between planes equal to 0.394 nm diffracts X-rays with a wavelength of 0.147 nm. What is the angle for the first order diffraction?

Portrait of a Chemist: X-ray Crystallographer Rosalind Franklin

Figure 20. This illustration shows an X-ray diffraction image similar to the one Franklin found in her research. (credit: National Institutes of Health)

The discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953 by Francis Crick and James Watson is one of the great achievements in the history of science. They were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with Maurice Wilkins, who provided experimental proof of DNA’s structure. British chemist Rosalind Franklin made invaluable contributions to this monumental achievement through her work in measuring X-ray diffraction images of DNA. Early in her career, Franklin’s research on the structure of coals proved helpful to the British war effort. After shifting her focus to biological systems in the early 1950s, Franklin and doctoral student Raymond Gosling discovered that DNA consists of two forms: a long, thin fiber formed when wet (type “B”) and a short, wide fiber formed when dried (type “A”). Her X-ray diffraction images of DNA (Figure 20) provided the crucial information that allowed Watson and Crick to confirm that DNA forms a double helix, and to determine details of its size and structure.

Franklin also conducted pioneering research on viruses and the RNA that contains their genetic information, uncovering new information that radically changed the body of knowledge in the field. After developing ovarian cancer, Franklin continued to work until her death in 1958 at age 37. Among many posthumous recognitions of her work, the Chicago Medical School of Finch University of Health Sciences changed its name to the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in 2004, and adopted an image of her famous X-ray diffraction image of DNA as its official university logo.

Key Concepts and Summary

The structures of crystalline metals and simple ionic compounds can be described in terms of packing of spheres. Metal atoms can pack in hexagonal closest-packed structures, cubic closest-packed structures, body-centered structures, and simple cubic structures. The anions in simple ionic structures commonly adopt one of these structures, and the cations occupy the spaces remaining between the anions. Small cations usually occupy tetrahedral holes in a closest-packed array of anions. Larger cations usually occupy octahedral holes. Still larger cations can occupy cubic holes in a simple cubic array of anions. The structure of a solid can be described by indicating the size and shape of a unit cell and the contents of the cell. The type of structure and dimensions of the unit cell can be determined by X-ray diffraction measurements.

Key Equations

- [latex]n{\lambda }=2d\text{sin}\theta [/latex]

Exercises

- Describe the crystal structure of iron, which crystallizes with two equivalent metal atoms in a cubic unit cell.

- Describe the crystal structure of Pt, which crystallizes with four equivalent metal atoms in a cubic unit cell.

- What is the coordination number of a chromium atom in the body-centered cubic structure of chromium?

- What is the coordination number of an aluminum atom in the face-centered cubic structure of aluminum?

- Cobalt metal crystallizes in a hexagonal closest packed structure. What is the coordination number of a cobalt atom?

- Nickel metal crystallizes in a cubic closest packed structure. What is the coordination number of a nickel atom?

- Tungsten crystallizes in a body-centered cubic unit cell with an edge length of 3.165 Å.

- What is the atomic radius of tungsten in this structure?

- Calculate the density of tungsten.

- Platinum (atomic radius = 1.38 Å) crystallizes in a cubic closely packed structure. Calculate the edge length of the face-centered cubic unit cell and the density of platinum.

- Barium crystallizes in a body-centered cubic unit cell with an edge length of 5.025 Å

- What is the atomic radius of barium in this structure?

- Calculate the density of barium.

- Aluminum (atomic radius = 1.43 Å) crystallizes in a cubic closely packed structure. Calculate the edge length of the face-centered cubic unit cell and the density of aluminum.

- The density of aluminum is 2.7 g/cm3; that of silicon is 2.3 g/cm3. Explain why Si has the lower density even though it has heavier atoms.

- The free space in a metal may be found by subtracting the volume of the atoms in a unit cell from the volume of the cell. Calculate the percentage of free space in each of the three cubic lattices if all atoms in each are of equal size and touch their nearest neighbors. Which of these structures represents the most efficient packing? That is, which packs with the least amount of unused space?

- Cadmium sulfide, sometimes used as a yellow pigment by artists, crystallizes with cadmium, occupying one-half of the tetrahedral holes in a closest packed array of sulfide ions. What is the formula of cadmium sulfide? Explain your answer.

- A compound of cadmium, tin, and phosphorus is used in the fabrication of some semiconductors. It crystallizes with cadmium occupying one-fourth of the tetrahedral holes and tin occupying one-fourth of the tetrahedral holes in a closest packed array of phosphide ions. What is the formula of the compound? Explain your answer.

- What is the formula of the magnetic oxide of cobalt, used in recording tapes, that crystallizes with cobalt atoms occupying one-eighth of the tetrahedral holes and one-half of the octahedral holes in a closely packed array of oxide ions?

- A compound containing zinc, aluminum, and sulfur crystallizes with a closest-packed array of sulfide ions. Zinc ions are found in one-eighth of the tetrahedral holes and aluminum ions in one-half of the octahedral holes. What is the empirical formula of the compound?

- A compound of thallium and iodine crystallizes in a simple cubic array of iodide ions with thallium ions in all of the cubic holes. What is the formula of this iodide? Explain your answer.

- Which of the following elements reacts with sulfur to form a solid in which the sulfur atoms form a closest-packed array with all of the octahedral holes occupied: Li, Na, Be, Ca, or Al?

- What is the percent by mass of titanium in rutile, a mineral that contains titanium and oxygen, if structure can be described as a closest packed array of oxide ions with titanium ions in one-half of the octahedral holes? What is the oxidation number of titanium?

- Explain why the chemically similar alkali metal chlorides NaCl and CsCl have different structures, whereas the chemically different NaCl and MnS have the same structure.

- As minerals were formed from the molten magma, different ions occupied the same cites in the crystals. Lithium often occurs along with magnesium in minerals despite the difference in the charge on their ions. Suggest an explanation.

- Rubidium iodide crystallizes with a cubic unit cell that contains iodide ions at the corners and a rubidium ion in the center. What is the formula of the compound?

- One of the various manganese oxides crystallizes with a cubic unit cell that contains manganese ions at the corners and in the center. Oxide ions are located at the center of each edge of the unit cell. What is the formula of the compound?

- NaH crystallizes with the same crystal structure as NaCl. The edge length of the cubic unit cell of NaH is 4.880 Å.

- Calculate the ionic radius of H−. (The ionic radius of Li+ is 0.0.95 Å.)

- Calculate the density of NaH.

- Thallium(I) iodide crystallizes with the same structure as CsCl. The edge length of the unit cell of TlI is 4.20 Å.

- Calculate the ionic radius of TI+. (The ionic radius of I− is 2.16 Å.)

- Calculate the density of TlI.

- A cubic unit cell contains manganese ions at the corners and fluoride ions at the center of each edge.

- What is the empirical formula of this compound? Explain your answer.

- What is the coordination number of the Mn3+ ion?

- Calculate the edge length of the unit cell if the radius of a Mn3+ ion is 0.65 A.

- Calculate the density of the compound.

- What is the spacing between crystal planes that diffract X-rays with a wavelength of 1.541 nm at an angle θ of 15.55° (first order reflection)?

- A diffractometer using X-rays with a wavelength of 0.2287 nm produced first-order diffraction peak for a crystal angle θ = 16.21°. Determine the spacing between the diffracting planes in this crystal.

- A metal with spacing between planes equal to 0.4164 nm diffracts X-rays with a wavelength of 0.2879 nm. What is the diffraction angle for the first order diffraction peak?

- Gold crystallizes in a face-centered cubic unit cell. The second-order reflection (n = 2) of X-rays for the planes that make up the tops and bottoms of the unit cells is at θ = 22.20°. The wavelength of the X-rays is 1.54 Å. What is the density of metallic gold?

- When an electron in an excited molybdenum atom falls from the L to the K shell, an X-ray is emitted. These X-rays are diffracted at an angle of 7.75° by planes with a separation of 2.64 Å. What is the difference in energy between the K shell and the L shell in molybdenum assuming a first-order diffraction?

Glossary

body-centered cubic (BCC) solid: crystalline structure that has a cubic unit cell with lattice points at the corners and in the center of the cell

body-centered cubic unit cell: simplest repeating unit of a body-centered cubic crystal; it is a cube containing lattice points at each corner and in the center of the cube

Bragg equation: equation that relates the angles at which X-rays are diffracted by the atoms within a crystal

coordination number: number of atoms closest to any given atom in a crystal or to the central metal atom in a complex

cubic closest packing (CCP): crystalline structure in which planes of closely packed atoms or ions are stacked as a series of three alternating layers of different relative orientations (ABC)

diffraction: redirection of electromagnetic radiation that occurs when it encounters a physical barrier of appropriate dimensions

face-centered cubic (FCC) solid: crystalline structure consisting of a cubic unit cell with lattice points on the corners and in the center of each face

face-centered cubic unit cell: simplest repeating unit of a face-centered cubic crystal; it is a cube containing lattice points at each corner and in the center of each face

hexagonal closest packing (HCP): crystalline structure in which close packed layers of atoms or ions are stacked as a series of two alternating layers of different relative orientations (AB)

hole: (also, interstice) space between atoms within a crystal

isomorphous: possessing the same crystalline structure

octahedral hole: open space in a crystal at the center of six particles located at the corners of an octahedron

simple cubic unit cell: (also, primitive cubic unit cell) unit cell in the simple cubic structure

simple cubic structure: crystalline structure with a cubic unit cell with lattice points only at the corners

space lattice: all points within a crystal that have identical environments

tetrahedral hole: tetrahedral space formed by four atoms or ions in a crystal

unit cell: smallest portion of a space lattice that is repeated in three dimensions to form the entire lattice

X-ray crystallography: experimental technique for determining distances between atoms in a crystal by measuring the angles at which X-rays are diffracted when passing through the crystal