One of the towering figures of impressionism in music, though he did not approve of that term being applied to his music, is Claude Debussy. A child prodigy and difficult personality, his innovations are seen as the beginnings of modernism in music.

Introduction

Claude-Achille Debussy (22 August 1862–25 March 1918) was a French composer. Along with Maurice Ravel, he was one of the most prominent figures associated withImpressionist music, though he himself disliked the term when applied to his compositions. He was madeChevalier of the Legion of Honour in his native France in 1903. Debussy was among the most influential composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and his use of non-traditional scales and chromaticism influenced many composers who followed.

Debussy’s music is noted for its sensory content and frequent usage of atonality. The prominent French literary style of his period was known as Symbolism, and this movement directly inspired Debussy both as a composer and as an active cultural participant.

Early Life

Debussy was born Achille-Claude Debussy (he later reversed his forenames) on 22 August 1862 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, the oldest of five children. His father, Manuel-Achille Debussy, owned a china shop there; his mother, Victorine Manoury Debussy, was a seamstress. The family moved to Paris in 1867, but in 1870 Debussy’s pregnant mother fled with Claude to his paternal aunt’s home in Cannes to escape the Franco-Prussian War. Debussy began piano lessons there at the age of seven with an Italian violinist in his early 40s named Cerutti; his aunt paid for his lessons. In 1871 he drew the attention of Marie Mauté de Fleurville, who claimed to have been a pupil of Frédéric Chopin. Debussy always believed her, although there is no independent evidence to support her claim. His talents soon became evident, and in 1872, at age ten, Debussy entered the Paris Conservatoire, where he spent the next 11 years. During his time there he studied composition with Ernest Guiraud, music history/theory with Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray, harmony with Émile Durand, piano with Antoine François Marmontel, organ with César Franck, and solfège with Albert Lavignac, as well as other significant figures of the era. He also became a lifelong friend of fellow student and distinguished pianist Isidor Philipp. After Debussy’s death, many pianists sought Philipp’s advice on playing Debussy’s works.

Musical Development

Debussy was argumentative and experimental from the outset, although clearly talented. He challenged the rigid teaching of the Academy, favoring instead dissonances and intervals that were frowned upon. Like Georges Bizet, he was a brilliant pianist and an outstanding sight reader, who could have had a professional career had he so wished. The pieces he played in public at this time included sonata movements by Beethoven, Schumann andWeber, and Chopin’s Ballade No. 2, a movement from the Piano Concerto No. 1, and the Allegro de concert.

During the summers of 1880, 1881, and 1882, Debussy accompanied Nadezhda von Meck, the wealthy patroness of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, as she travelled with her family in Europe. The young composer’s many musical activities during these vacations included playing four-hand pieces with von Meck at the piano, giving music lessons to her children, and performing in private concerts with some of her musician friends. Despite von Meck’s closeness to Tchaikovsky, the Russian master appears to have had minimal effect on Debussy. In September 1880 she sent Debussy’s Danse bohémienne for Tchaikovsky’s perusal. A month later Tchaikovsky wrote back to her: “It is a very pretty piece, but it is much too short. Not a single idea is expressed fully, the form is terribly shriveled, and it lacks unity.” Debussy did not publish the piece, and the manuscript remained in the von Meck family; it was eventually sold to B. Schott’s Sohne in Mainz, and published by them in 1932.

A greater influence was Debussy’s close friendship with Marie-Blanche Vasnier, a singer he met when he began working as an accompanist to earn some money, embarking on an eight-year affair together. She and her husband, Parisian civil servant Henri, gave Debussy emotional and professional support. Henri Vasnier introduced him to the writings of influential French writers of the time, which gave rise to his first songs, settings of poems by Paul Verlaine (the son-in-law of his former teacher Mme. Mauté de Fleurville).

As the winner of the 1884 Prix de Rome with his composition L’enfant prodigue, Debussy received a scholarship to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which included a four-year residence at the Villa Medici, the French Academy in Rome, to further his studies (1885–1887). According to letters to Marie-Blanche Vasnier, perhaps in part designed to gain her sympathy, he found the artistic atmosphere stifling, the company boorish, the food bad, and the monastic quarters “abominable.” Neither did he delight in Italian opera, as he found the operas of Donizetti andVerdi not to his taste. Debussy was often depressed and unable to compose, but he was inspired by Franz Liszt, whose command of the keyboard he found admirable. In June 1885, Debussy wrote of his desire to follow his own way, saying, “I am sure the Institute would not approve, for, naturally it regards the path which it ordains as the only right one. But there is no help for it! I am too enamoured of my freedom, too fond of my own ideas!”

Debussy finally composed four pieces that were sent to the Academy: the symphonic ode Zuleima (based on a text by Heinrich Heine); the orchestral piece Printemps; the cantata La damoiselle élue (1887–1888) (which was criticized by the Academy as “bizarre,” although it was the first piece in which the stylistic features of Debussy’s later style began to emerge); and the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra, which was heavily based on César Franck’s music and therefore eventually withdrawn by Debussy. The Academy chided him for “courting the unusual” and hoped for something better from the gifted student. Although Debussy’s works showed the influence of Jules Massenet, Massenet concluded, “He is an enigma.”

During his visits to Bayreuth in 1888–9, Debussy was exposed to Wagnerian opera, which would have a lasting impact on his work. Debussy, like many young musicians of the time, responded positively to Richard Wagner’s sensuousness, mastery of form, and striking harmonies. Wagner’s extroverted emotionalism was not to be Debussy’s way, but the German composer’s influence is evident in La damoiselle élue and the 1889 piece Cinq poèmes de Charles Baudelaire. Other songs of the period, notably the settings of Verlaine—Ariettes oubliées, Trois mélodies, and Fêtes galantes—are all in a more capricious style.

Around this time, Debussy met Erik Satie, who proved a kindred spirit in his experimental approach to composition and to naming his pieces. Both musicians were bohemians during this period, enjoying the same cafe society and struggling to stay afloat financially.

In 1889, at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, Debussy first heard Javanese gamelan music. He incorporated gamelan scales, melodies, rhythms, and ensemble textures into some of his compositions, most notably Pagodes from his piano collection Estampes.

Music Style

Rudolph Reti points out the following features of Debussy’s music, which “established a new concept of tonality in European music”:

- Glittering passages and webs of figurations which distract from occasional absence of tonality;

- Frequent use of parallel chords which are “in essence not harmonies at all, but rather ‘chordal melodies’, enriched unisons,” described by some writers as non-functional harmonies;

- Bitonality, or at least bitonal chords;

- Use of the whole-tone and pentatonic scale;

- Unprepared modulations, “without any harmonic bridge.”

He concludes that Debussy’s achievement was the synthesis of monophonic based “melodic tonality” with harmonies, albeit different from those of “harmonic tonality.”

The application of the term “Impressionist” to Debussy and the music he influenced is a matter of intense debate within academic circles. One side argues that the term is a misnomer, an inappropriate label which Debussy himself opposed. In a letter of 1908 he wrote: “I am trying to do ‘something different’ — an effect of reality . . . what the imbeciles call ‘impressionism’, a term which is as poorly used as possible, particularly by the critics, since they do not hesitate to apply it to [J.M.W.] Turner, the finest creator of mysterious effects in all the world of art.” The opposing side argues that Debussy may have been reacting to unfavorable criticism at the time, and the negativity that critics associated with Impressionism; it could therefore be argued that he would have been pleased with application of the current definition of Impressionism to his music.

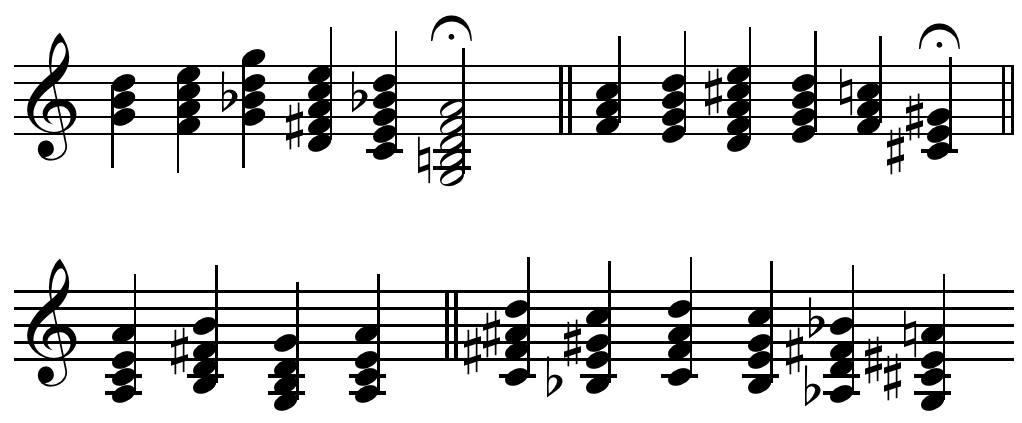

Figure 3.Chords, featuring chromatically altered sevenths and ninths and progressing unconventionally, explored by Debussy in a “celebrated conversation at the piano with his teacher Ernest Guiraud”

Candela Citations

- Claude Debussy. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Debussy. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike