- How does the Federal Reserve manage the money supply?

Before the twentieth century, there was very little government regulation of the U.S. financial or monetary systems. In 1907, however, several large banks failed, creating a public panic that led worried depositors to withdraw their money from other banks. Soon many other banks had failed, and the U.S. banking system was near collapse. The panic of 1907 was so severe that Congress created the Federal Reserve System in 1913 to provide the nation with a more stable monetary and banking system.

The Federal Reserve System (commonly called the Fed) is the central bank of the United States. The Fed’s primary mission is to oversee the nation’s monetary and credit system and to support the ongoing operation of America’s private-banking system. The Fed’s actions affect the interest rates banks charge businesses and consumers, help keep inflation under control, and ultimately stabilize the U.S. financial system. The Fed operates as an independent government entity. It derives its authority from Congress but its decisions do not have to be approved by the president, Congress, or any other government branch. However, Congress does periodically review the Fed’s activities, and the Fed must work within the economic framework established by the government.

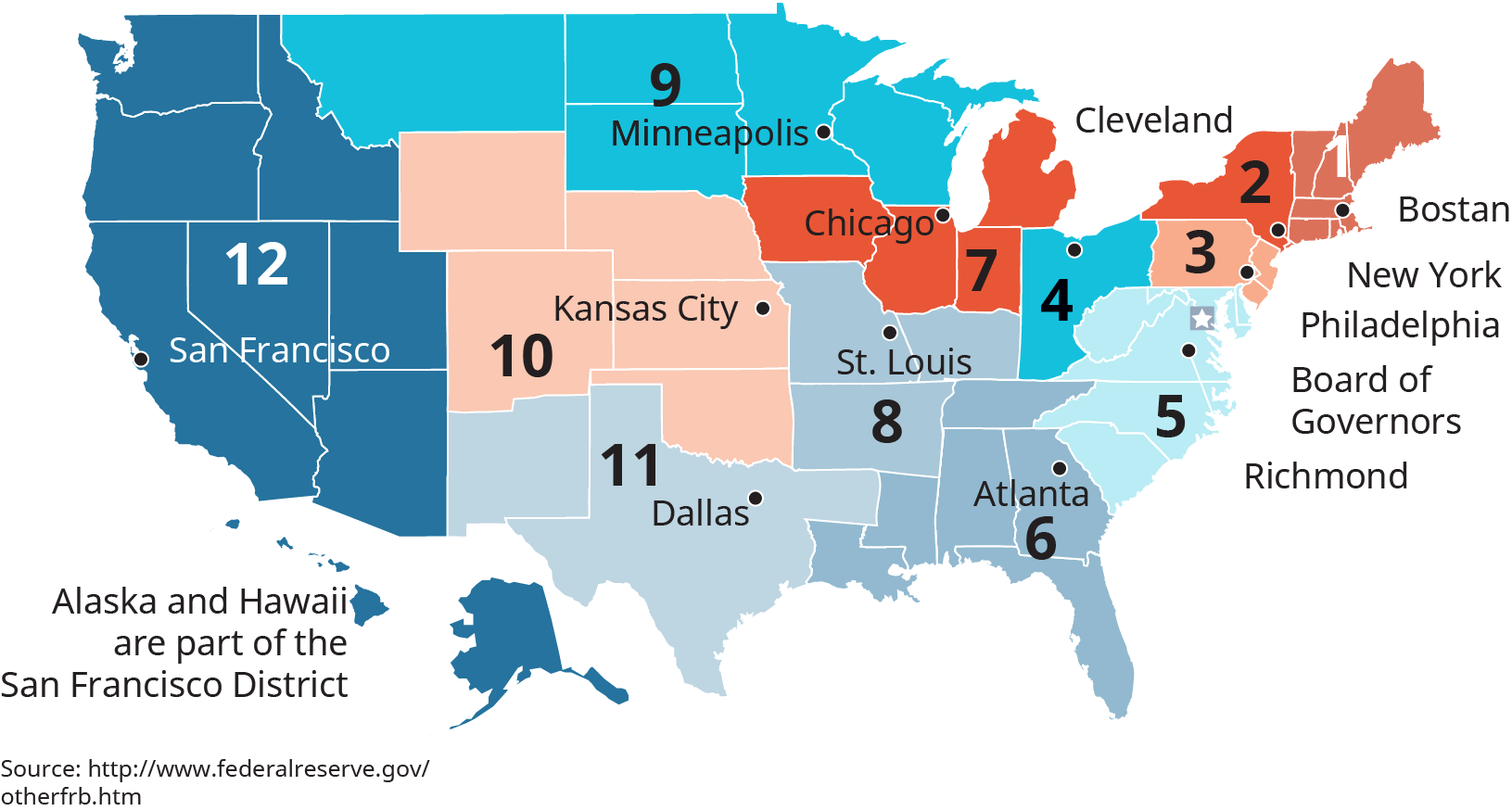

The Fed consists of 12 district banks, each covering a specific geographic area. (Figure) shows the 12 districts of the Federal Reserve. Each district has its own bank president who oversees operations within that district.

Originally, the Federal Reserve System was created to control the money supply, act as a borrowing source for banks, hold the deposits of member banks, and supervise banking practices. Its activities have since broadened, making it the most powerful financial institution in the United States. Today, four of the Federal Reserve System’s most important responsibilities are carrying out monetary policy, setting rules on credit, distributing currency, and making check clearing easier.

Exhibit 15.3 Federal Reserve Districts and Banks Source: “Federal Reserve Banks,” https://www.richmondfed.org, accessed September 7, 2017.

Carrying Out Monetary Policy

The most important function of the Federal Reserve System is carrying out monetary policy. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is the Fed policy-making body that meets eight times a year to make monetary policy decisions. It uses its power to change the money supply in order to control inflation and interest rates, increase employment, and influence economic activity. Three tools used by the Federal Reserve System in managing the money supply are open market operations, reserve requirements, and the discount rate. (Figure) summarizes the short-term effects of these tools on the economy.

Open market operations—the tool most frequently used by the Federal Reserve—involve the purchase or sale of U.S. government bonds. The U.S. Treasury issues bonds to obtain the extra money needed to run the government (if taxes and other revenues aren’t enough). In effect, Treasury bonds are long-term loans (five years or longer) made by businesses and individuals to the government. The Federal Reserve buys and sells these bonds for the Treasury. When the Federal Reserve buys bonds, it puts money into the economy. Banks have more money to lend, so they reduce interest rates, which generally stimulates economic activity. The opposite occurs when the Federal Reserve sells government bonds.

| The Federal Reserve System’s Monetary Tools and Their Effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool | Action | Effect on Money Supply | Effect on Interest Rates | Effect on Economic Activity |

| Open market operations | Buy government bonds | Increases | Lowers | Stimulates |

| Sell government bonds | Decreases | Raises | Slows Down | |

| Reserve requirements | Raise reserve requirements | Decreases | Raises | Slows Down |

| Lower reserve requirements | Increases | Lowers | Stimulates | |

| Discount rate | Raise discount rate | Decreases | Raises | Slows Down |

| Lower discount rate | Increases | Lowers | Stimulates | |

Banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System must hold some of their deposits in cash in their vaults or in an account at a district bank. This reserve requirement ranges from 3 to 10 percent on different types of deposits. When the Federal Reserve raises the reserve requirement, banks must hold larger reserves and thus have less money to lend. As a result, interest rates rise, and economic activity slows down. Lowering the reserve requirement increases loanable funds, causes banks to lower interest rates, and stimulates the economy; however, the Federal Reserve seldom changes reserve requirements.

The Federal Reserve is called “the banker’s bank” because it lends money to banks that need it. The interest rate that the Federal Reserve charges its member banks is called the discount rate. When the discount rate is less than the cost of other sources of funds (such as certificates of deposit), commercial banks borrow from the Federal Reserve and then lend the funds at a higher rate to customers. The banks profit from the spread, or difference, between the rate they charge their customers and the rate paid to the Federal Reserve. Changes in the discount rate usually produce changes in the interest rate that banks charge their customers. The Federal Reserve raises the discount rate to slow down economic growth and lowers it to stimulate growth.

Setting Rules on Credit

Another activity of the Federal Reserve System is setting rules on credit. It controls the credit terms on some loans made by banks and other lending institutions. This power, called selective credit controls, includes consumer credit rules and margin requirements. Consumer credit rules establish the minimum down payments and maximum repayment periods for consumer loans. The Federal Reserve uses credit rules to slow or stimulate consumer credit purchases. Margin requirements specify the minimum amount of cash an investor must put up to buy securities or investment certificates issued by corporations or governments. The balance of the purchase cost can be financed through borrowing from a bank or brokerage firm. By lowering the margin requirement, the Federal Reserve stimulates securities trading. Raising the margin requirement slows trading.

Distributing Currency: Keeping the Cash Flowing

The Federal Reserve distributes the coins minted and the paper money printed by the U.S. Treasury to banks. Most paper money is in the form of Federal Reserve notes. Look at a dollar bill and you’ll see “Federal Reserve Note” at the top. The large letter seal on the left indicates which Federal Reserve Bank issued it. For example, bills bearing a D seal are issued by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, and those with an L seal are issued by the San Francisco district bank.

Making Check Clearing Easier

Another important activity of the Federal Reserve is processing and clearing checks between financial institutions. When a check is cashed at a financial institution other than the one holding the account on which the check is drawn, the Federal Reserve’s system lets that financial institution—even if distant from the institution holding the account on which the check is drawn—quickly convert the check into cash. Checks drawn on banks within the same Federal Reserve district are handled through the local Federal Reserve Bank using a series of bookkeeping entries to transfer funds between the financial institutions. The process is more complex for checks processed between different Federal Reserve districts.

The time between when the check is written and when the funds are deducted from the check writer’s account provides float. Float benefits the check writer by allowing it to retain the funds until the check clears—that is, when the funds are actually withdrawn from its accounts. Businesses open accounts at banks around the country that are known to have long check-clearing times. By “playing the float,” firms can keep their funds invested for several extra days, thus earning more money. To reduce this practice, in 1988 the Fed established maximum check-clearing times. However, as credit cards and other types of electronic payments have become more popular, the use of checks continues to decline. Responding to this decline, the Federal Reserve scaled back its check-processing facilities over the past decade. Current estimates suggest that the number of check payments has declined by two billion annually over the last couple of years and will continue to do so as more people use online banking and other electronic payment systems.[1]

Managing the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis

Much has been written over the past decade about the global financial crisis that occurred between 2007 and 2009. Some suggest that without the Fed’s intervention, the U.S. economy would have slipped deeper into a financial depression that could have lasted years. Several missteps by banks, mortgage lenders, and other financial institutions, which included approving consumers for home mortgages they could not afford and then packaging those mortgages into high-risk financial products sold to investors, put the U.S. economy into serious financial trouble.[2]

In the early 2000s, the housing industry was booming. Mortgage lenders were signing up consumers for mortgages that “on paper” they could afford. In many instances, lenders told consumers that based on their credit rating and other financial data, they could easily take the next step and buy a bigger house or maybe a vacation home because of the availability of mortgage money and low interest rates. When the U.S. housing bubble burst in late 2007, the value of real estate plummeted, and many consumers struggled to pay mortgages on houses no longer worth the value they borrowed to buy the properties, leaving their real estate investments “underwater.” Millions of consumers simply walked away from their houses, letting them go into foreclosure while filing personal bankruptcy. At the same time, the overall economy was going into a recession, and millions of people lost their jobs as companies tightened their belts to try to survive the financial upheaval affecting the United States as well as other countries across the globe.[3]

In addition, several leading financial investment firms, particularly those that managed and sold the high-risk, mortgage-backed financial products, failed quickly because they had not set aside enough money to cover the billions of dollars they lost on mortgages now going into default. For example, the venerable financial company Bear Stearns, which had been a successful business for more than 85 years, was eventually sold to JP Morgan for less than $10 a share, even after the Federal Reserve made more than $50 billion dollars available to help prop up financial institutions in trouble.[4]

After the collapse of Bear Stearns and other firms such as Lehman Brothers and insurance giant AIG, the Fed set up a special loan program to stabilize the banking system and to keep the U.S. bond markets trading at a normal pace. It is estimated that the Federal Reserve made more than $9 trillion in loans to major banks and other financial firms during the two-year crisis—not to mention bailing out the auto industry and buying several other firms to keep the financial system afloat.[5]

As a result of this financial meltdown, Congress passed legislation in 2010 to implement major regulations in the financial industry to prevent the future collapse of financial institutions, as well to put a check on abusive lending practices by banks and other firms. Among its provisions, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (known as Dodd-Frank) created an oversight council to monitor risks that affect the financial industry; requires banks to increase their cash reserves if the council feels the bank has too much risk in its current operations; prohibits banks from owning, investing, or sponsoring hedge funds, private equity funds, or other proprietary trading operations for profit; and set up a whistle-blower program to reward people who come forward to report security and other financial violations.[6]

Another provision of Dodd-Frank legislation requires major U.S. banks to submit to annual stress tests conducted by the Federal Reserve. These annual checkups determine whether banks have enough capital to survive economic turbulence in the financial system and whether the institutions can identify and measure risk as part of their capital plan to pay dividends or buy back shares. In 2017, seven years after Dodd-Frank became law, all of the country’s major banks passed the annual examination.[7]

Exhibit 15.4 The Federal Reserve kept short-term interest rates close to 0 percent for more than seven years, from 2009 to December 2015, as a result of the global financial crisis. Now that the economy seems to be recovering at a slow but steady pace, the Fed began to raise the interest rate to 1.00–1.25 percent in mid-2017. What effect do higher interest rates have on the U.S. economy? (Credit: ./ Pexels/ CC0 License/✓ Free for personal and commercial use/✓ No attribution required)

Key Takeaways

- What are the four key functions of the Federal Reserve System?

- What three tools does the Federal Reserve System use to manage the money supply, and how does each affect economic activity?

- What was the Fed’s role in keeping the U.S. financial markets solvent during the 2007–2009 financial crisis?

Summary of Learning Outcomes

- How does the Federal Reserve manage the money supply?

The Federal Reserve System (the Fed) is an independent government agency that performs four main functions: carrying out monetary policy, setting rules on credit, distributing currency, and making check clearing easier. The three tools it uses in managing the money supply are open market operations, reserve requirements, and the discount rate. The Fed played a major role in keeping the U.S. financial system solvent during the financial crisis of 2007–2009 by making more than $9 trillion available in loans to major banks and other financial firms, in addition to bailing out the auto industry and other companies and supporting congressional passage of Dodd-Frank federal legislation.

Glossary

- discount rate

- The interest rate that the Federal Reserve charges its member banks.

- Federal Reserve System (Fed)

- The central bank of the United States; consists of 12 district banks, each located in a major U.S. city.

- open market operations

- The purchase or sale of U.S. government bonds by the Federal Reserve to stimulate or slow down the economy.

- reserve requirement

- Requires banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System to hold some of their deposits in cash in their vaults or in an account at a district bank.

- selective credit controls

- The power of the Federal Reserve to control consumer credit rules and margin requirements.

Candela Citations

- Intro to Business. Authored by: Gitman, et. al. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/4e09771f-a8aa-40ce-9063-aa58cc24e77f@8.2. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/4e09771f-a8aa-40ce-9063-aa58cc24e77f@8.2

- “The Federal Reserve Payments Study 2016,” https://www.federalreserve.gov, accessed September 7, 2017; Brad Kvederis, “The Paper Check Lives: Why the Check Decline Slowed in 2016,” http://fi.deluxe.com, January 19, 2017. ↵

- “BLS Spotlight on Statistics: The Recession of 2007–2009,” http://www.bls.gov/spotlight, accessed September 7, 2017. ↵

- “Predatory Lending,” The Economist, https://www.economist.com, accessed September 7, 2017; Steve Denning, “Lest We Forget: Why We Had a Financial Crisis,” Forbes, http://www.forbes.com, November 22, 2011. ↵

- Kimberly Amadeo, “What Is Too Big to Fail? With Examples of Banks,” The Balance, https://www.thebalance.com, accessed September 7, 2017; John Maxfield, “A Timeline of Bear Stearns' Downfall,” The Motley Fool, https://www.fool.com, accessed September 7, 2017. ↵

- Chris Isidore, “Fed Made $9 Trillion in Emergency Overnight Loans,” CNN Money, http://money.cnn.com, accessed September 7, 2017. ↵

- Mark Koba, “Dodd-Frank Act: CNBC Explains,” CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com, accessed September 7, 2017. ↵

- James McBride, “The Role of the U.S. Federal Reserve,” Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org, accessed September 7, 2017; Donna Borak, “For the First Time, All U.S. Banks Pass Fed’s Stress Tests,” CNN Money, http://money.cnn.com, June 28, 2017. ↵