Learning Objective

- Discuss intrapersonal communication.

- Define and discuss self-concept.

- Understand the role of interpersonal needs in the communication process.

When you answer the question, “What are you doing?” what do you write? Eating at your favorite restaurant? Working on a slow evening? Reading your favorite book on a Kindle? Preferring the feel of paper to keyboard? Reading by candlelight? In each case, you are communicating what you are doing, but you may not be communicating why, or what it means to you. That communication may be internal, but is it only an internal communication process?

Intrapersonal communication can be defined as communication with one’s self, and that may include self-talk, acts of imagination and visualization, and even recall and memory (McLean, S., 2005). You read on your cell phone screen that your friends are going to have dinner at your favorite restaurant. What comes to mind? Sights, sounds, and scents? Something special that happened the last time you were there? Do you contemplate joining them? Do you start to work out a plan of getting from your present location to the restaurant? Do you send your friends a text asking if they want company? Until the moment when you hit the “send” button, you are communicating with yourself.

Communications expert Leonard Shedletsky (1989) examines intrapersonal communication through the eight basic components of the communication process (i.e., source, receiver, message, channel, feedback, environment, context, and interference) as transactional, but all the interaction occurs within the individual. Perhaps, as you consider whether to leave your present location and join your friends at the restaurant, you are aware of all the work that sits in front of you. You may hear the voice of your boss, or perhaps of one of your parents, admonishing you about personal responsibility and duty. On the other hand, you may imagine the friends at the restaurant saying something to the effect of “you deserve some time off!”

At the same time as you argue with yourself, Judy Pearson and Paul Nelson would be quick to add that intrapersonal communication is not only your internal monologue but also involves your efforts to plan how to get to the restaurant (Pearson & Nelson, 1985). From planning to problem-solving, internal conflict resolution, and evaluations and judgments of self and others, we communicate with ourselves through intrapersonal communication.

All this interaction takes place in the mind without externalization, and all of it relies on previous interaction with the external world. If you had been born in a different country, to different parents, what language would you speak? What language would you think in? What would you value, what would be important to you, and what would not? Even as you argue to yourself whether the prospect of joining your friends at the restaurant overcomes your need to complete your work, you use language and symbols that were communicated to you. Your language and culture have given you the means to rationalize, act, and answer the question, “What are you doing?” but you are still bound by the expectations of yourself and the others who make up your community.

Exercises

- Describe what you are doing, pretending you are another person observing yourself. Write your observations down or record them with a voice or video recorder. Discuss the exercise with your classmates.

- Think of a time when you have used self-talk—for example, giving yourself “I can do this!” messages when you are striving to meet a challenge, or “what’s the use?” messages when you are discouraged. Did you purposely choose to use self-talk, or did it just happen? Discuss your thoughts with classmates.

- Take a few minutes and visualize what you would like your life to be like a year from now, or five years from now. Do you think this visualization exercise will influence your actions and decisions in the future? Compare your thoughts with those of your classmates.

Again we’ll return to the question “what are you doing?” as one way to approach self-concept. If we define ourselves through our actions, what might those actions be, and are we no longer ourselves when we no longer engage in those activities? Psychologist Steven Pinker defines the conscious present as about three seconds for most people. Everything else is past or future (Pinker, S., 2009). Who are you at this moment in time, and will the self you become an hour from now be different from the self that is reading this sentence right now?

Just as the communication process is dynamic, not static (i.e., always changing, not staying the same), you too are a dynamic system. Physiologically your body is in a constant state of change as you inhale and exhale air, digest food, and cleanse waste from each cell. Psychologically you are constantly in a state of change as well. Some aspects of your personality and character will be constant, while others will shift and adapt to your environment and context. That complex combination contributes to the self you call yourself. We may choose to define self as one’s own sense of individuality, personal characteristics, motivations, and actions (McLean, 2005), but any definition we create will fail to capture who you are, and who you will become.

Self-Concept

Our self-concept is “what we perceive ourselves to be” (McLean, 2005) and involves aspects of image and esteem. How we see ourselves and how we feel about ourselves influences how we communicate with others. What you are thinking now and how you communicate impacts and influences how others treat you. Charles Cooley calls this concept the looking-glass self. We look at how others treat us, what they say and how they say it, for clues about how they view us to gain insight into our own identity. Leon Festinger added that we engage in social comparisons, evaluating ourselves in relation to our peers of similar status, similar characteristics, or similar qualities (Festinger, 1954).

The ability to think about how, what, and when we think, and why, is critical to intrapersonal communication. Animals may use language and tools, but can they reflect on their own thinking? Self-reflection is a trait that allows us to adapt and change to our context or environment, accept or reject messages, examine our concept of ourselves, and choose to improve.

Internal monologue refers to the self-talk of intrapersonal communication. It can be a running monologue that is rational and reasonable, or disorganized and illogical. It can interfere with listening to others, impede your ability to focus, and become a barrier to effective communication. Alfred Korzybski suggested that the first step in becoming conscious of how we think and communicate with ourselves was to achieve an inner quietness, in effect “turning off” our internal monologue (Korzybski, 1933). Learning to be quiet inside can be a challenge. We can choose to listen to others when they communicate through the written or spoken word while refraining from preparing our responses before they finish their turn is essential. We can take mental note of when we jump to conclusions from only partially attending to the speaker or writer’s message. We can choose to listen to others instead of ourselves.

One principle of communication is that interaction is always dynamic and changing. That interaction can be internal, as in intrapersonal communication, but can also be external. We may communicate with one other person and engage in interpersonal communication. If we engage two or more individuals (up to eight normally), group communication is the result. More than eight normally results in subdivisions within the group and a reversion to smaller groups of three to four members (McLean, 2005) due to the ever-increasing complexity of the communication process. With each new person comes a multiplier effect on the number of possible interactions, and for many that means the need to establish limits.

Dimensions of Self

Who are you? You are more than your actions, and more than your communication, and the result may be greater than the sum of the parts, but how do you know yourself? If you were asked to define yourself in five words or less, could you do it? Can five words capture the essence of what you consider yourself to be? Would a twenty to fifty description be easier? Or would it be equally challenging? Did your description focus on your characteristics, beliefs, actions, or other factors associated with you? If you compare your results with classmates or coworkers, what did you observe? For many, these exercises can prove challenging as we try to reconcile the self-concept we perceive with what we desire others to perceive about us, as we try to see ourselves through our interactions with others, and as we come to terms with the idea that we may not be aware or know everything there is to know about ourselves.

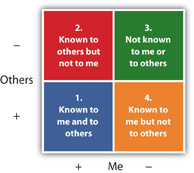

Joseph Luft and Harry Ingram gave considerable thought and attention to these dimensions of self, which are represented in Figure 2.1 “Luft and Ingram’s Dimensions of Self”. In the first quadrant of the figure, information is known to you and others, such as your height or weight. The second quadrant represents things others observe about us that we are unaware of, like how many times we say “umm” in the space of five minutes. The third quadrant involves information that you know, but do not reveal to others. It may involve actively hiding or withholding information or may involve social tact, such as thanking your Aunt Martha for the large purple hat she’s given you that you know you will never wear. Finally, the fourth quadrant involves information that is unknown to you and your conversational partners. For example, a childhood experience that has been long forgotten or repressed may still motivate you. As another example, how will you handle an emergency after you’ve received first aid training? No one knows because it has not happened.

These dimensions of self serve to remind us that we are not fixed—that freedom to change combined with the ability to reflect, anticipate, plan, and predict allows us to improve, learn, and adapt to our surroundings. By recognizing that we are not fixed in our concept of “self,” we come to terms with the responsibility and freedom inherent in our potential humanity.

In the context of business communication, the self plays a central role. How do you describe yourself? Do your career path, job responsibilities, goals, and aspirations align with what you recognize to be your talents? How you represent “self,” through your résumé, in your writing, your articulation, and presentation—these all play an important role as you negotiate the relationships and climate present in any organization.

Exercises

- Examine your academic or professional résumé—or, if you don’t have one, create one now. According to the dimensions of self described in this section, which dimensions contribute to your résumé? Discuss your results with your classmates.

- How would you describe yourself in terms of the dimensions of self as shown in Figure 2.1 “Luft and Ingram’s Dimensions of Self”? Discuss your thoughts with a classmate.

- Can you think of a job or career that would be a good way for you to express yourself? Are you pursuing that job or career? Why or why not? Discuss your answer with a classmate.

Active Listening and Reading

You’ve probably experienced the odd sensation of driving somewhere and, having arrived, have realized you don’t remember driving. Your mind may have been filled with other issues and you drove on autopilot. It’s dangerous when you drive like that, and it is dangerous in communication. Choosing to listen or read attentively takes effort. People communicate with words, expressions, and even in silence, and your attention to them will make you a better communicator. From discussions on improving customer service to retaining customers in challenging economic times, the importance of listening comes up frequently as a success strategy.

Here are some tips to facilitate active listening and reading:

- Maintain eye contact with the speaker; if reading, keep your eyes on the page.

- Don’t interrupt; if reading, don’t multitask.

- Focus your attention on the message, not your internal monologue.

- Restate the message in your own words and ask if you understood correctly.

- Ask clarifying questions to communicate interest and gain insight.

References

Cooley, C. (1922). Human nature and the social order (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Scribners.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of soical comparison processes. Human Relationships, 7, 117–140.

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and sanity. Lancaster, PA: International Non-Aristotelian Library Publish Co.

Luft, J. (1970). Group processes: An introduction to group dynamics (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: National Press Group.

Luft, J., & Ingham, H. (1955). The Johari Window: A graphic model for interpersonal relations. Los Angeles: University of California Western Training Lab.

Candela Citations

- 16.1 Intrapersonal Communication in Business Communication for Success. Authored by: University of Minnesota. Located at: https://open.lib.umn.edu/businesscommunication/chapter/16-1-intrapersonal-communication/%20. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 16.2 Self-Concept and Dimensions of Self in Business Communication for Success. Authored by: University of Minnesota. Located at: https://open.lib.umn.edu/businesscommunication/chapter/16-2-self-concept-and-dimensions-of-self/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 16.3 Interpersonal Needs in Business Communication for Success. Authored by: University of Minnesota. Located at: https://open.lib.umn.edu/businesscommunication/chapter/16-3-interpersonal-needs/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike