What you’ll learn to do: Evaluate and practice preliminary, intermediate, and advanced search techniques

Have you ever heard a song, made a mental note to look up its name, but then forgot all of the words? You remember wanting to hear it again and add it to your workout playlist, but all you remember is a short bit of the tune? How did you go about finding the song?

Chances are, you had to:

Chances are, you had to:

- Investigate to find out the song’s melody. Maybe you hummed the tune for a few friends, or remember that it sounded somewhat similar to another song you already heard, and used that song as a reference point.

- Investigate to find out the song’s title (“E.T.,” “The Lazy Song,” “Born This Way,” “Latinoamérica”).

- Investigate to find out who performed the song (Lady Gaga, Bruno Mars, Katy Perry, Maroon 5, Kanye West, Calle 13).

- Investigate to find out what CD that song was on (Teenage Dream, Doo-Wops & Hooligans, Born This Way, Entren Los Que Quieran) and if there are other songs you might also enjoy.

- Investigate to find out where you can purchase or download the song for the best price.

You can’t—and won’t—get what you want without investigating. And it’s really no different with researching. Investigating is essential to your research because the questions you ask and the places you look will give you the results you need to create a convincing and compelling argument. Researching will take time and effort, so it pays off to take the time up front to learn about the best strategies for maximizing your research in order to identify and utilize the best sources. The wrong approach can waste your time and effort and result in a weak paper or report.

So, where do you start investigating? First, you’ll want to follow the research process. Once you have a good understanding of your research assignment and goals, you can begin to search for the right sources. In this section, you’ll learn how follow the research process in order to carefully use search engines and library databases to find articles you’ll need to write a top notch paper.

Learning Outcomes

- Evaluate preliminary research strategies

- Discuss common tools and strategies for completing online searches

- Identify tools used to find scholarly secondary sources

Preliminary Research Strategies

As we have discussed, all research is based upon your research question. Having a well-defined and scoped question is essential to a good research strategy. If your question is not specific enough, or if it lacks boundaries (i.e., it is not well-scoped), your subsequent strategy will be difficult to maintain.

Steely Library discusses developing a good research question in the video below:

The Human Fund

Let’s return to Martha’s case. We can recall that her research question was,

“Is The Human Fund’s work helping homeless families in downtown Chicago?”

If we first break her question down into its sub-parts, developing a research strategy will be much easier. Her question asks,

- Is The Human Fund’s work — i.e., what The Human Fund does — its actions

- helping — i.e., we must define “helping” in relation to…

- …the homeless families…

- …in downtown Chicago?

From her question, we know that we will need sources that,

- Outline The Human Fund’s activities

- Define how charities and government help the homeless in their cities

- Help to define and understand “homeless”

- Are geographically bound to downtown Chicago

With the above in mind, any secondary source that does not specifically address a part of the question above—and how it is broken down—will be off topic or out of scope.

We will also recall that Martha conducted background reading (i.e., secondary source reading) before determining the type of primary source material (i.e., fieldwork and interviews with the homeless) she would use. This can be confusing; when we research, we do background or secondary source reading before determining what primary source material might still be needed. You will not typically see a research process that advocates doing primary source research when there is already secondary source material available on a given topic because it is not efficient. It is also important to note that if secondary source material sufficiently addresses your research question, consider this to be a win; this means that the much slower and much more elaborate primary source research process is no longer required. Your report will be that much faster to compile. If Martha, for example, had recent accounts of interviews with homeless people in downtown Chicago about The Human Fund’s work, she would not need to conduct her own interviews.

practice questions

Finding Sources

For our purposes here, and with respect to business report writing, it’s important to know how to make the most of generic online searches. While Google Scholar and library databases will be the most valuable tools for finding academic information, many business reports will only need information that is easily available from Google. As you find sources pertinent to your report, be sure to keep track of them so you can cite and reference them later.

When you search for information using keywords in Google, you may yield thousands or millions of search results, and they do not appear in order of credibility or relevance. Use a cautious eye and try different keywords or various combinations in order to find different results. You can also try using different Boolean operators (words like AND, OR, or NOT), or use the Google advanced search features to narrow down your results. Work to simplify your search phrases, and be patient in moving through results pages.

Preliminary Search Tips

- Wikipedia can be a great starting point for information, but depending on your research, it is not recommended for use as an official source. It’s helpful to look at the links and references at the bottom of the page for more ideas.

- Use “Ctrl+F” to find certain words within a webpage in order to jump to the sections of the article that interest you.

- Use Google Advanced Search to be more specific in your search. You can also use tricks to be more specific within the main Google Search Engine:

- Use quotation marks to narrow your search from just tanks in WWII to “Tanks in WWII” or “Tanks” in “WWII”.

- Find specific types of websites by adding “site:.gov” or “site:.edu” or “site:.org”. You can also search for specific file types like “filetype:.pdf”.

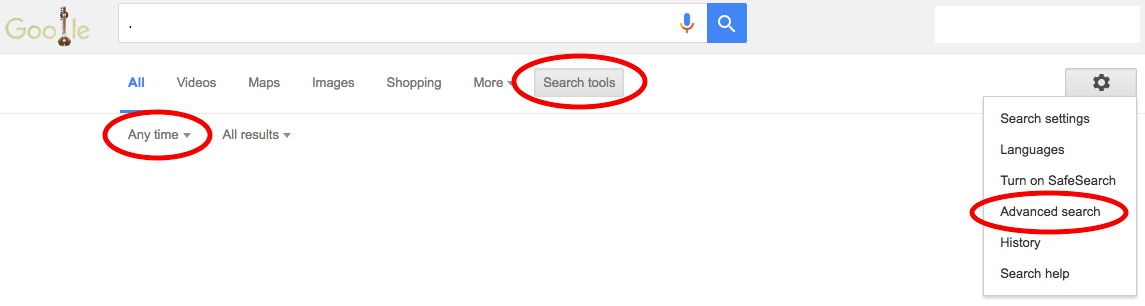

- Click on “Search Tools” under the search bar in Google and select “Any time” to see a list of options for time periods to help limit your search. You can find information just in the past month or year, or even for a custom range.

Use features already available through Google Search, such as Search Tools and Advanced Search to narrow and refine your results.

practice question

Using Databases

In the event Google or other search engines do not yield quality sources, you may find yourself requiring higher level library access. This brings us to two other areas for secondary source material:

- Google Scholar

- Library databases

Google Scholar

Google Scholar is an excellent and more refined version of Google that focuses on professional literature. While you can use Google Scholar for free, the results will likely be paywall-protected academic material, so you will need a library for access. Some public libraries offer this for free to their constituents, or if you are a faculty or student at a college or university, you also can gain immediate access to paid content. What Google Scholar can help you gather free of charge is awareness about what type of data may exist. This is important for your business report writing. If data exists, but only behind a paywall, then you may consider conducting your own primary source development (i.e, your own fieldwork such as surveys or interviews) depending on how robust your report needs to be.

For our purposes here, look at Figure 1 and compare the results of the captured search to the previous searches where we just used a standard Google search.

Figure 1. An example search in Google Scholar

One of the things that Google Scholar does very well is tell you what type of source it is right away. Note how the first listing is a book published in 2002. This book is likely readily available in a library, or it could be purchased online. The sources in Figure 1 are a mix of other books and articles in professional journals.

Practice Questions

Library Databases

As mentioned above, in order to access professional journals, you will need higher-end and paywall-guarded database access. However, some institutions (particularly institutions with more academic leanings) will provide their employees with access to these. Public libraries also often have access to many databases. Databases come in all shapes and sizes and are not necessarily just troves of quantitative figures and facts. The video below describes databases, and their use:

Finding Sources From Databases

If you have access to a library database, it can be a helpful tool in finding additional sources.

Subject Headings

Most databases will include related subject headings alongside each search result. Subject headings are a form of descriptive metadata. At their simplest, they may be tags chosen by the authors, but most databases use a controlled vocabulary assigned by professional catalogers

The advantage of controlled subject terms is that they’re standardized terms that will be assigned to all appropriate content no matter what terminology (or even language) is used by the author. For example, the database Academic Search Complete uses the subject term “motion pictures,” even if the article uses the words “films,” “movies,” or “cinema.”

Whenever you find a good article in a database, check out the subject headings. If one or more of them look like matches for your topic, re-run your search using those terms—and be sure to specify you want those terms in the subject field. That will ensure the search results are really about that subject and don’t just happen to mention those words in passing somehow.

Follow the Bibliographic Links

As long as you find one good scholarly article or book, you can look up the works cited in the footnotes or bibliography to find the sources it’s based on.

You can also follow citations forward in time by looking up who cited the work you have. Web of Science has cited reference searches.

Candela Citations

- Screenshot of Google Search engine results page. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Screenshot of the Google Scholar search engine. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image of guitar. Authored by: erin m. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/8Fskd1. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Pot of Gold Research Tutorial. Provided by: University of Notre Dame. Located at: http://library.nd.edu/instruction/potofgold/investigating/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Introduction to Finding Sources. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-englishcomposition1/chapter/outcome-finding-sources-3-1/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Finding Sources from Sources. Provided by: UCLA Library. Located at: http://guides.library.ucla.edu/c.php?g=180896&p=1185263. Project: Choosing and Using Library Databases. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Developing a Research Question. Authored by: Steely Library NKU. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LWLYCYeCFak. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- What Are Databases and Why You Need Them. Authored by: Yavapai College Library. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q2GMtIuaNzU. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License