Learning Objectives

- Define the concept of an attitude and explain why it is of such interest to social psychologists.

- Review the variables that determine attitude strength.

- Outline the factors that affect the strength of the attitude-behavior relationship.

Although we might use the term in a different way in our everyday life (e.g., “Hey, he’s really got an attitude!”), social psychologists reserve the term attitude to refer to our relatively enduring evaluation of something, where the something is called the attitude object. The attitude object might be a person, a product, or a social group (Albarracín, Johnson, & Zanna, 2005; Wood, 2000). In this section, we will consider the nature and strength of attitudes and the conditions under which attitudes best predict our behaviors.

Attitudes Are Evaluations

When we say that attitudes are evaluations, we mean that they involve a preference for or against the attitude object, as commonly expressed in terms such as prefer, like, dislike, hate, and love. When we express our attitudes—for instance, when we say, “I like swimming,” “I hate snakes,” or “I love my parents” —we are expressing the relationship (either positive or negative) between the self and an attitude object. Statements such as these make it clear that attitudes are an important part of the self-concept.

Every human being holds thousands of attitudes, including those about family and friends, political figures, abortion rights, terrorism, preferences for music, and much more. Each of our attitudes has its own unique characteristics, and no two attitudes come to us or influence us in quite the same way. Research has found that some of our attitudes are inherited, at least in part, via genetic transmission from our parents (Olson, Vernon, Harris, & Jang, 2001). Other attitudes are learned mostly through direct and indirect experiences with the attitude objects (De Houwer, Thomas, & Baeyens, 2001). We may like to ride roller coasters in part because our genetic code has given us a thrill-loving personality and in part because we’ve had some really great times on roller coasters in the past. Still other attitudes are learned via the media (Hargreaves & Tiggemann, 2003; Levina, Waldo, & Fitzgerald, 2000) or through our interactions with friends (Poteat, 2007). Some of our attitudes are shared by others (most of us like sugar, fear snakes, and are disgusted by cockroaches), whereas other attitudes—such as our preferences for different styles of music or art—are more individualized.

Table 4.1, “Heritability of Some Attitudes,” shows some of the attitudes that have been found to be the most highly heritable (i.e., most strongly determined by genetic variation among people). These attitudes form earlier and are stronger and more resistant to change than others (Bourgeois, 2002), although it is not yet known why some attitudes are more genetically determined than are others.

Table 4.1 Heritability of Some Attitudes

| Attitude | Heritability |

|---|---|

| Abortion on demand | 0.54 |

| Roller coaster rides | 0.52 |

| Death penalty for murder | 0.5 |

| Organized religion | 0.45 |

| Doing athletic activities | 0.44 |

| Voluntary euthanasia | 0.44 |

| Capitalism | 0.39 |

| Playing chess | 0.38 |

| Reading books | 0.37 |

| Exercising | 0.36 |

| Education | 0.32 |

| Big parties | 0.32 |

| Smoking | 0.31 |

| Being the center of attention | 0.28 |

| Getting along well with other people | 0.28 |

| Wearing clothes that draw attention | 0.24 |

| Sweets | 0.22 |

| Public speaking | 0.2 |

| Castration as punishment for sex crimes | 0.17 |

| Loud music | 0.11 |

| Looking my best at all times | 0.1 |

| Doing crossword puzzles | 0.02 |

| Separate roles for men and women | 0 |

| Making racial discrimination illegal | 0 |

| Playing organized sports | 0 |

| Easy access to birth control | 0 |

| Being the leader of groups | 0 |

| Being assertive | 0 |

| Ranked from most heritable to least heritable. Data are from Olson, Vernon, Harris, and Jang (2001). Olson, J. M., Vernon, P. A., Harris, J. A., Harris, J.A., & Jang, K. L. (2001). The heritability of attitudes: A study of twins. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(6), 845–860. | |

Our attitudes are made up of cognitive, affective, and behavioral components. Consider an environmentalist’s attitude toward recycling, which is probably very positive:

- In terms of affect: They feel happy when they recycle.

- In terms of behavior: They regularly recycle their bottles and cans.

- In terms of cognition: They believe recycling is the responsible thing to do.

Although most attitudes are determined by affect, behavior, and cognition, there is nevertheless variability in this regard across people and across attitudes. Some attitudes are more likely to be based on feelings, some are more likely to be based on behaviors, and some are more likely to be based on beliefs. For example, your attitude toward chocolate ice cream is probably determined in large part by affect—although you can describe its taste, mostly you may just like it. Your attitude toward your toothbrush, on the other hand, is probably more cognitive (you understand the importance of its function). Still other of your attitudes may be based more on behavior. For example, your attitude toward note-taking during lectures probably depends, at least in part, on whether or not you regularly take notes.

Different people may hold attitudes toward the same attitude object for different reasons. For example, some people vote for politicians because they like their policies, whereas others vote for (or against) politicians because they just like (or dislike) their public persona. Although you might think that cognition would be more important in this regard, political scientists have shown that many voting decisions are made primarily on the basis of affect. Indeed, it is fair to say that the affective component of attitudes is generally the strongest and most important (Abelson, Kinder, Peters, & Fiske, 1981; Stangor, Sullivan, & Ford, 1991).

Human beings hold attitudes because they are useful. Particularly, our attitudes enable us to determine, often very quickly and effortlessly, which behaviors to engage in, which people to approach or avoid, and even which products to buy (Duckworth, Bargh, Garcia, & Chaiken, 2002; Maio & Olson, 2000). You can imagine that making quick decisions about what to avoid or approach has had substantial value in our evolutionary experience. For example:

- Snake = bad ⟶ run away

- Blueberries = good ⟶ eat

Because attitudes are evaluations, they can be assessed using any of the normal measuring techniques used by social psychologists (Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010). Attitudes are frequently assessed using self-report measures, but they can also be assessed more indirectly using measures of arousal and facial expressions (Mendes, 2008) as well as implicit measures of cognition, such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Attitudes can also be seen in the brain by using neuroimaging techniques. This research has found that our attitudes, like most of our social knowledge, are stored primarily in the prefrontal cortex but that the amygdala is important in emotional attitudes, particularly those associated with fear (Cunningham, Raye, & Johnson, 2004; Cunningham & Zelazo, 2007; van den Bos, McClure, Harris, Fiske, & Cohen, 2007). Attitudes can be activated extremely quickly—often within one-fifth of a second after we see an attitude object (Handy, Smilek, Geiger, Liu, & Schooler, 2010).

Some Attitudes Are Stronger Than Others

Some attitudes are more important than others because they are more useful to us and thus have more impact on our daily lives. The importance of an attitude, as assessed by how quickly it comes to mind, is known as attitude strength (Fazio, 1990; Fazio, 1995; Krosnick & Petty, 1995). Some of our attitudes are strong attitudes, in the sense that we find them important, hold them with confidence, do not change them very much, and use them frequently to guide our actions. These strong attitudes may guide our actions completely out of our awareness (Ferguson, Bargh, & Nayak, 2005).

Other attitudes are weaker and have little influence on our actions. For instance, John Bargh and his colleagues (Bargh, Chaiken, Raymond, & Hymes, 1996) found that people could express attitudes toward nonsense words such as juvalamu (which people liked) and chakaka (which they did not like). The researchers also found that these attitudes were very weak.

Strong attitudes are more cognitively accessible—they come to mind quickly, regularly, and easily. We can easily measure attitude strength by assessing how quickly our attitudes are activated when we are exposed to the attitude object. If we can state our attitude quickly, without much thought, then it is a strong one. If we are unsure about our attitude and need to think about it for a while before stating our opinion, the attitude is weak.

Attitudes become stronger when we have direct positive or negative experiences with the attitude object, and particularly if those experiences have been in strong positive or negative contexts. Russell Fazio and his colleagues (Fazio, Powell, & Herr, 1983) had people either work on some puzzles or watch other people work on the same puzzles. Although the people who watched ended up either liking or disliking the puzzles as much as the people who actually worked on them, Fazio found that attitudes, as assessed by reaction time measures, were stronger (in the sense of being expressed quickly) for the people who had directly experienced the puzzles.

Because attitude strength is determined by cognitive accessibility, it is possible to make attitudes stronger by increasing the accessibility of the attitude. This can be done directly by having people think about, express, or discuss their attitudes with others. After people think about their attitudes, talk about them, or just say them out loud, the attitudes they have expressed become stronger (Downing, Judd, & Brauer, 1992; Tesser, Martin, & Mendolia, 1995). Because attitudes are linked to the self-concept, they also become stronger when they are activated along with the self-concept. When we are looking into a mirror or sitting in front of a TV camera, our attitudes are activated and we are then more likely to act on them (Beaman, Klentz, Diener, & Svanum, 1979).

Attitudes are also stronger when the ABCs of affect, behavior, and cognition all align. As an example, many people’s attitude toward their own nation is universally positive. They have strong positive feelings about their country, many positive thoughts about it, and tend to engage in behaviors that support it. Other attitudes are less strong because the affective, cognitive, and behavioral components are each somewhat different (Thompson, Zanna, & Griffin, 1995). Your cognitions toward physical exercise may be positive—you believe that regular physical activity is good for your health. On the other hand, your affect may be negative—you may resist exercising because you prefer to engage in tasks that provide more immediate rewards. Consequently, you may not exercise as often as you believe you ought to. These inconsistencies among the components of your attitude make it less strong than it would be if all the components lined up together.

When Do Our Attitudes Guide Our Behavior?

Social psychologists (as well as advertisers, marketers, and politicians) are particularly interested in the behavioral aspect of attitudes. Because it is normal that the ABCs of our attitudes are at least somewhat consistent, our behavior tends to follow from our affect and cognition. If I determine that you have more positive cognitions about and more positive affect toward waffles than French toast, then I will naturally predict (and probably be correct when I do so) that you’ll be more likely to order waffles than French toast when you eat breakfast at a restaurant. Furthermore, if I can do something to make your thoughts or feelings toward French toast more positive, then your likelihood of ordering it for breakfast will also increase.

The principle of attitude consistency (that for any given attitude object, the ABCs of affect, behavior, and cognition are normally in line with each other) thus predicts that our attitudes (for instance, as measured via a self-report measure) are likely to guide behavior. Supporting this idea, meta-analyses have found that there is a significant and substantial positive correlation among the different components of attitudes, and that attitudes expressed on self-report measures do predict behavior (Glasman & Albarracín, 2006).

However, our attitudes are not the only factor that influence our decision to act. The theory of planned behavior, developed by Martin Fishbein and Izek Ajzen (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), outlines three key variables that affect the attitude-behavior relationship: (a) the attitude toward the behaviour (the stronger the better), (b) subjective norms (the support of those we value), and (c) perceived behavioral control (the extent to which we believe we can actually perform the behavior). These three factors jointly predict our intention to perform the behavior, which in turn predicts our actual behavior (Figure 4.2, “Theory of Planned Behavior”).

To illustrate, imagine for a moment that your friend Sharina is trying to decide whether to recycle her used laptop batteries or just throw them away. We know that her attitude toward recycling is positive—she thinks she should do it—but we also know that recycling takes work. It’s much easier to just throw the batteries away. But if Sharina feels strongly about the importance of recycling, if her family and friends are also in favor of recycling, and if she has easy access to a battery recycling facility, then she will develop a strong intention to perform the behavior and likely follow through on it.

Since it was first proposed, the theory of planned behavior has grown to become an extremely influential model for predicting human social behavior. However, although it has been used to study virtually every kind of planned behavior, a recent meta-analysis of 206 articles found that this model was especially effective at predicting physical activity and dietary behaviors (McEachan, Conner, Taylor, & Lawton, 2011).

Figure 4.2 Theory of Planned Behavior, adapted by Hilda Aggregani under CC BY.

More generally, research has also discovered that attitudes predict behaviors well only under certain conditions and for some people. These include:

- When the attitude and the behavior both occur in similar social situations

- When the same components of the attitude (either affect or cognition) are accessible when the attitude is assessed and when the behavior is performed

- When the attitudes are measured at a specific, rather than a general, level

- For low self-monitors (rather than for high self-monitors)

The extent of the match between the social situations in which the attitudes are expressed and the behaviors are engaged in is important; there is a greater attitude-behavior correlation when the social situations match. Imagine for a minute the case of Magritte, a 16-year-old high school student. Magritte tells her parents that she hates the idea of smoking cigarettes. Magritte’s negative attitude toward smoking seems to be a strong one because she’s thought a lot about it—she believes that cigarettes are dirty, expensive, and unhealthy. But how sure are you that Magritte’s attitude will predict her behavior? Would you be willing to bet that she’d never try smoking when she’s out with her friends?

You can see that the problem here is that Magritte’s attitude is being expressed in one social situation (when she is with her parents), whereas the behavior (trying a cigarette) is going to occur in a very different social situation (when she is out with her friends). The relevant social norms are of course much different in the two situations. Magritte’s friends might be able to convince her to try smoking, despite her initial negative attitude, when they entice her with peer pressure. Behaviors are more likely to be consistent with attitudes when the social situation in which the behavior occurs is similar to the situation in which the attitude is expressed (Ajzen, 1991; LaPiere, 1936).

Research Focus

Attitude-Behavior Consistency

Another variable that has an important influence on attitude-behavior consistency is the current cognitive accessibility of the underlying affective and cognitive components of the attitude. For example, if we assess the attitude in a situation in which people are thinking primarily about the attitude object in cognitive terms, and yet the behavior is performed in a situation in which the affective components of the attitude are more accessible, then the attitude-behavior relationship will be weak. Wilson and Schooler (1991) showed a similar type of effect by first choosing attitudes that they expected would be primarily determined by affect—attitudes toward five different types of strawberry jam. They asked a sample of college students to taste each of the jams. While they were tasting, one-half of the participants were instructed to think about the cognitive aspects of their attitudes to these jams—that is, to focus on the reasons they held their attitudes—whereas the other half of the participants were not given these instructions. Then all the students completed measures of their attitudes toward each of the jams.

Wilson and his colleagues then assessed the extent to which the attitudes expressed by the students correlated with taste ratings of the five jams as indicated by experts at Consumer Reports. They found that the attitudes expressed by the students correlated significantly higher with the expert ratings for the participants who had not listed their cognitions first. Wilson and his colleagues argued that this occurred because our liking of jams is primarily affectively determined—we either like them or we don’t. And the students who simply rated the jams used their feelings to make their judgments. On the other hand, the students who were asked to list their thoughts about the jams had some extra information to use in making their judgments, but it was information that was not actually useful. Therefore, when these students used their thoughts about the jam to make the judgments, their judgments were less valid.

MacDonald, Zanna, and Fong (1996) showed male college students a video of two other college students, Mike and Rebecca, who were out on a date. According to random assignment to conditions, half of the men were shown the video while sober and the other half viewed the video after they had had several alcoholic drinks. In the video, Mike and Rebecca go to the campus bar and drink and dance. They then go to Rebecca’s room, where they end up kissing passionately. Mike says that he doesn’t have any condoms, but Rebecca says that she is on the pill.

At this point the film clip ends, and the male participants are asked about their likely behaviors if they had been Mike. Although all men indicated that having unprotected sex in this situation was foolish and irresponsible, the men who had been drinking alcohol were more likely to indicate that they would engage in sexual intercourse with Rebecca even without a condom. One interpretation of this study is that sexual behavior is determined by both cognitive factors (e.g., “I know that it is important to practice safe sex and so I should use a condom”) and affective factors (e.g., “Sex is enjoyable, I don’t want to wait”). When the students were intoxicated at the time the behavior was to be performed, it seems likely the affective component of the attitude was a more important determinant of behavior than was the cognitive component.

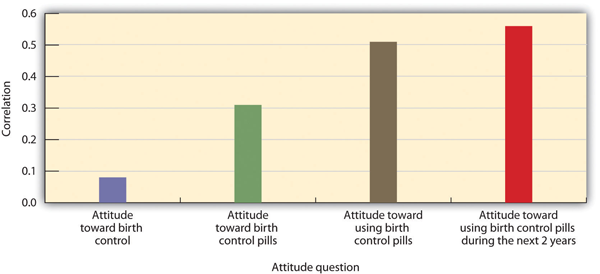

One other type of match that has an important influence on the attitude-behavior relationship concerns how we measure the attitude and behavior. Attitudes predict behavior better when the attitude is measured at a level that is similar to the behavior to be predicted. Normally, the behavior is specific, so it is better to measure the attitude at a specific level too. For instance, if we measure cognitions at a very general level (e.g., “Do you think it is important to use condoms?”; “Are you a religious person?”) we will not be as successful at predicting actual behaviors as we will be if we ask the question more specifically, at the level of behavior we are interested in predicting (e.g., “Do you think you will use a condom the next time you have sex?”; “How frequently do you expect to attend church in the next month?”). In general, more specific questions are better predictors of specific behaviors, and thus if we wish to accurately predict behaviors, we should remember to attempt to measure specific attitudes. One example of this principle is shown in Figure 4.3, “Predicting Behavior from Specific and Nonspecific Attitude Measures.” Davidson and Jaccard (1979) found that they were much better able to predict whether women actually used birth control when they assessed the attitude at a more specific level.

Figure 4.3 Predicting Behavior from Specific and Nonspecific Attitude Measures. Attitudes that are measured using more specific questions are more highly correlated with behavior than are attitudes measured using less specific questions. Data are from Davidson and Jaccard (1979).Davidson, A. R., & Jaccard, J. J. (1979). Variables that moderate the attitude-behavior relation: Results of a longitudinal survey. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(8), 1364–1376.

Attitudes also predict behavior better for some people than for others. As we saw in Chapter 3, self-monitoring refers to individual differences in the tendency to attend to social cues and to adjust one’s behavior to one’s social environment. To return to our example of Magritte, you might wonder whether she is the type of person who is likely to be persuaded by peer pressure because she is particularly concerned with being liked by others. If she is, then she’s probably more likely to want to fit in with whatever her friends are doing, and she might try a cigarette if her friends offer her one. On the other hand, if Magritte is not particularly concerned about following the social norms of her friends, then she’ll more likely be able to resist the persuasion. High self-monitors are those who tend to attempt to blend into the social situation in order to be liked; low self-monitors are those who are less likely to do so. You can see that, because they allow the social situation to influence their behaviors, the relationship between attitudes and behavior will be weaker for high self-monitors than it is for low self-monitors (Kraus, 1995).

Key Takeaways

- The term attitude refers to our relatively enduring evaluation of an attitude object.

- Our attitudes are inherited and also learned through direct and indirect experiences with the attitude objects.

- Some attitudes are more likely to be based on beliefs, some are more likely to be based on feelings, and some are more likely to be based on behaviors.

- Strong attitudes are important in the sense that we hold them with confidence, we do not change them very much, and we use them frequently to guide our actions.

- Although there is a general consistency between attitudes and behavior, the relationship is stronger in some situations than in others, for some measurements than for others, and for some people than for others.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Describe an example of a behavior that you engaged in that might be explained by the theory of planned behavior. Include each of the components of the theory in your analysis.

- Consider a time when you acted on your own attitudes and a time when you did not act on your own attitudes. What factors do you think determined the difference?

References

Abelson, R. P., Kinder, D. R., Peters, M. D., & Fiske, S. T. (1981). Affective and semantic components in political person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 619–630.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Albarracín, D., Johnson, B. T., & Zanna, M. P. (Eds.). (2005). The handbook of attitudes (pp. 223–271). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Banaji, M. R., & Heiphetz, L. (2010). Attitudes. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 353–393). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Bargh, J. A., Chaiken, S., Raymond, P., & Hymes, C. (1996). The automatic evaluation effect: Unconditional automatic attitude activation with a pronunciation task. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 32(1), 104–128.

Beaman, A. L., Klentz, B., Diener, E., & Svanum, S. (1979). Self-awareness and transgression in children: Two field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(10), 1835–1846.

Bourgeois, M. J. (2002). Heritability of attitudes constrains dynamic social impact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(8), 1063–1072.

Cunningham, W. A., & Zelazo, P. D. (2007). Attitudes and evaluations: A social cognitive neuroscience perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(3), 97–104;

Cunningham, W. A., Raye, C. L., & Johnson, M. K. (2004). Implicit and explicit evaluation: fMRI correlates of valence, emotional intensity, and control in the processing of attitudes. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16(10), 1717–1729;

Davidson, A. R., & Jaccard, J. J. (1979). Variables that moderate the attitude-behavior relation: Results of a longitudinal survey. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(8), 1364–1376.

De Houwer, J., Thomas, S., & Baeyens, F. (2001). Association learning of likes and dislikes: A review of 25 years of research on human evaluative conditioning. Psychological Bulletin, 127(6), 853-869.

Downing, J. W., Judd, C. M., & Brauer, M. (1992). Effects of repeated expressions on attitude extremity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(1), 17–29; Tesser, A., Martin, L., & Mendolia, M. (Eds.). (1995). The impact of thought on attitude extremity and attitude-behavior consistency. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Duckworth, K. L., Bargh, J. A., Garcia, M., & Chaiken, S. (2002). The automatic evaluation of novel stimuli. Psychological Science, 13(6), 513–519.

Fazio, R. H. (1990). The MODE model as an integrative framework. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 75–109;

Fazio, R. H. (1995). Attitudes as object-evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 247–282). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum;

Fazio, R. H., Powell, M. C., & Herr, P. M. (1983). Toward a process model of the attitude-behavior relation: Accessing one’s attitude upon mere observation of the attitude object. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(4), 723–735.

Ferguson, M. J., Bargh, J. A., & Nayak, D. A. (2005). After-affects: How automatic evaluations influence the interpretation of subsequent, unrelated stimuli. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(2), 182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.05.008

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 778–822.

Handy, T. C., Smilek, D., Geiger, L., Liu, C., & Schooler, J. W. (2010). ERP evidence for rapid hedonic evaluation of logos. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(1), 124–138. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21180

Hargreaves, D. A., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Female “thin ideal” media images and boys’ attitudes toward girls. Sex Roles, 49(9–10), 539–544.

Kraus, S. J. (1995). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(1), 58–75.

Krosnick, J. A., & Petty, R. E. (1995). Attitude strength: An overview. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 1–24). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

LaPiere, R. T. (1936). Type rationalization of group antipathy. Social Forces, 15, 232–237.

Levina, M., Waldo, C. R., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2000). We’re here, we’re queer, we’re on TV: The effects of visual media on heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(4), 738–758.

MacDonald, T. K., Zanna, M. P., & Fong, G. T. (1996). Why common sense goes out the window: Effects of alcohol on intentions to use condoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(8), 763–775.

Maio, G. R., & Olson, J. M. (Eds.). (2000). Why we evaluate: Functions of attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. doi:10.1080/17437199.2010.521684

McEachan, R. R. C., Conner, M., Taylor, N. J., & Lawton, R. J. (2011) Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis, Health Psychology Review, 5(2), 97-144.

Mendes, W. B. (2008). Assessing autonomic nervous system reactivity. In E. Harmon-Jones & J. Beer (Eds.), Methods in the neurobiology of social and personality psychology (pp. 118–147). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Olson, J. M., Vernon, P. A., Harris, J. A., & Jang, K. L. (2001). The heritability of attitudes: A study of twins. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(6), 845–860.

Poteat, V. P. (2007). Peer group socialization of homophobic attitudes and behavior during adolescence. Child Development, 78(6), 1830–1842.

Stangor, C., Sullivan, L. A., & Ford, T. E. (1991). Affective and cognitive determinants of prejudice. Social Cognition, 9(4), 359–380.

Tesser, A., Martin, L., & Mendolia, M. (1995). The impact of thought on attitude extremity and attitude-behavior consistency. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences. Ohio State University series on attitudes and persuasion (4th ed., pp. 73-92). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Thompson, M. M., Zanna, M. P., & Griffin, D. W. (1995). Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 361–386). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

van den Bos, W., McClure, S. M., Harris, L. T., Fiske, S. T., & Cohen, J. D. (2007). Dissociating affective evaluation and social cognitive processes in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(4), 337–346.

Wilson, T. D., & Schooler, J. W. (1991). Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 181–192.

Wood, W. (2000). Attitude change: Persuasion and social influence. Annual Review of Psychology, 539–570.

Candela Citations

- Principles of Social Psychology - 1st International Edition. Authored by: Rajiv Jhangiani, Hammond Tarry, and Charles Stangor. Provided by: BC Campus OpenEd. Located at: https://open.bccampus.ca/find-open-textbooks/?uuid=66c0cf64-c485-442c-8183-de75151f13f5&contributor=&keyword=&subject=. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike