The Whig Party, which had been created to oppose Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party, benefitted from the disaster of the Panic of 1837.

The Whig Party had grown partly out of the political coalition of John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. The National Republicans, a loose alliance concentrated in the Northeast, had become the core of a new anti-Jackson movement. But Jackson’s enemies were a varied group; they included proslavery southerners angry about Jackson’s behavior during the Nullification Crisis as well as antislavery Yankees.

After they failed to prevent Andrew Jackson’s reelection, this fragile coalition formally organized as a new party in 1834 “to rescue the Government and public liberty.” Henry Clay, who had run against Jackson for president and was now serving again as a senator from Kentucky, held private meetings to persuade anti-Jackson leaders from different backgrounds to unite. He also gave the new Whig Party its anti-monarchical name.

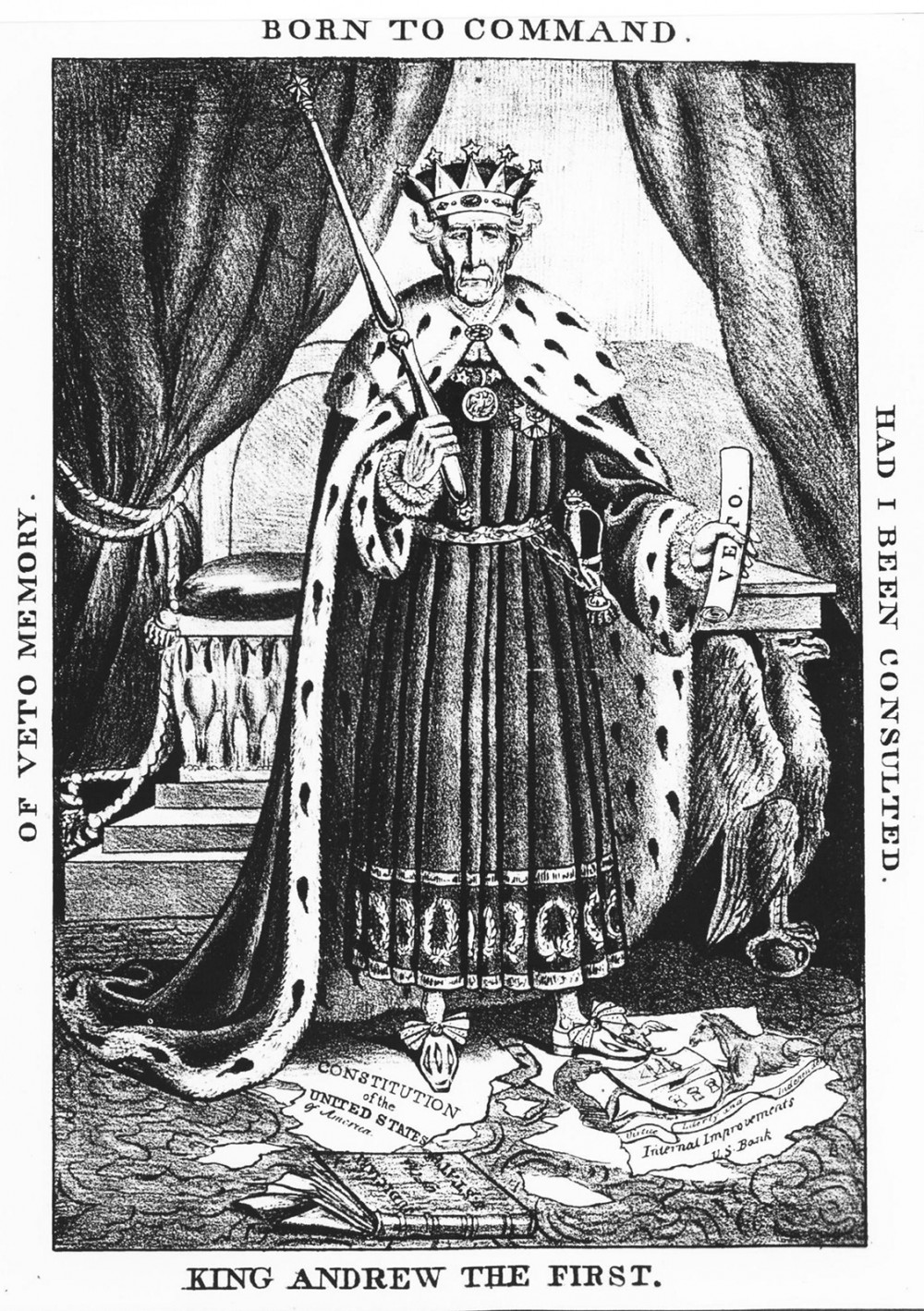

At first, the Whigs focused mainly on winning seats in Congress, opposing “King Andrew” from outside the presidency. They remained divided by regional and ideological differences. The Democratic presidential candidate, Vice President Martin Van Buren, easily won election as Jackson’s successor in 1836. But the Whigs gained significant public support after the Panic of 1837, and they became increasingly well-organized. In late 1839, they held their first national convention in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Andrew Jackson portrayed himself as the defender of the common man, and in many ways he democratized American politics. His opponents, however, zeroed in on Jackson’s willingness to utilize the powers of the executive office. Unwilling to defer to Congress and absolutely willing to use his veto power, Jackson came to be regarded by his adversaries as a tyrant (or, in this case, “King Andrew I”.) Anonymous, c. 1832. Wikimedia.

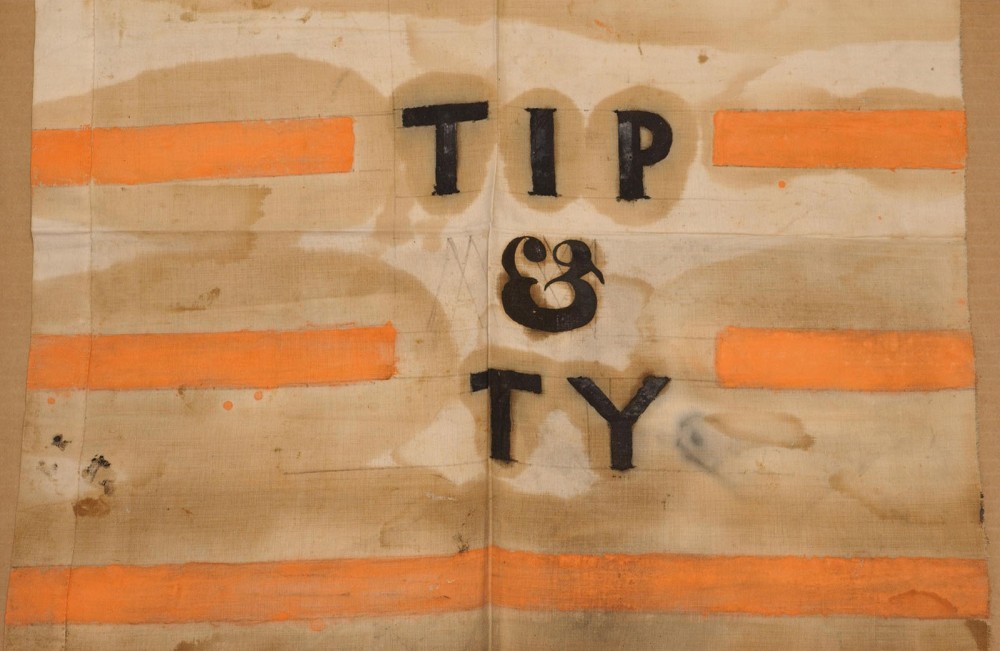

To Henry Clay’s disappointment, the convention voted to nominate not him but General William Henry Harrison of Ohio as the Whig candidate for president in 1840. Harrison was known primarily for defeating Shawnee warriors in the Northwest before and during the War of 1812, most famously at the Battle of Tippecanoe in present-day Indiana. Whig leaders viewed him as a candidate with broad patriotic appeal. They portrayed him as the “log cabin and hard cider” candidate, a plain man of the country, unlike the easterner Martin Van Buren. To balance the ticket with a southerner, the Whigs nominated a slaveowning Virginia senator, John Tyler, as vice president. Tyler had been a Jackson supporter but had broken with him over states’ rights during the Nullification Crisis.

“Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” was a popular and influential campaign song and slogan, helping the Whigs and William Henry Harrison (with John Tyler) win the presidential election in 1840. Pictured here is a campaign banner with shortened “Tip and Ty,” one of the many ways that Whigs made the “log cabin campaign” successful. Wikimedia.

Although “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too” easily won the presidential election of 1840, this choice of ticket turned out to be disastrous for the Whigs. Harrison became ill (for unclear reasons, though tradition claims he contracted pneumonia after delivering a nearly two-hour inaugural address without an overcoat or hat) and died after just thirty-one days in office. Harrison thus holds the ironic honor of having the longest inaugural address and the shortest term in office of any American president. Vice President Tyler became president and soon adopted policies that looked far more like Andrew Jackson’s than like a Whig’s. After Tyler twice vetoed charters for another Bank of the United States, nearly his entire cabinet resigned, and the Whigs in Congress expelled “His Accidency” from the party.

The crisis of Tyler’s administration was just one sign of the Whig Party’s difficulty uniting around issues besides opposition to Democrats. The Whig Party would succeed in electing two more presidents, but it would remain deeply divided. Its problems would grow as the issue of slavery strained the Union in the 1850s. Unable to agree upon a consistent national position on slavery, and unable to find another national issue to rally around, the Whigs would break apart by 1856.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike