The concept of family played a crucial role in the daily lives of enslaved African Americans in the Old South. Family represented an institution through which slaves pieced together communities and ultimately an entire world distinct from those who exploited them. Family ties provided slaves with identities apart from their master, connections with other slaves, and ways to preserve the traditions and beliefs of their own communities. These ties also provided networks to share news, resistance tactics, and advice of all kinds.

The nature and structure of the slave family changed over time. African-born slaves during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries typically engaged in unions—often polygamous—with those of the same ethnicity when possible. However, by around 1830, the growth of Christianity in slave communities increased the prevalence of nuclear families. By the start of the Civil War, approximately two-thirds of slaves were members of nuclear households, each household averaging six persons. The remaining third of slaves resided with only one or neither biological parent.

Many slave marriages endured for many years, although the threat of sale always loomed. The increased interstate slave trade after the turn of the nineteenth century accounted for the dissolution of hundreds of thousands of slave families. In the decades before the Civil War, between one-fifth and one-third of all slave marriages were broken up via sale or forced migration. Slaveholders also disrupted slave families for a variety of other reasons, selling slaves they considered disobedient, mutinous, unproductive, unhealthy, or even infertile. Law and custom that defined slaves as property enabled slaveholders to bequeath their slaves to heirs, present them as gifts, or offer them to settle debts.

Planters justified their position of power using the logic of paternalism. Paternalism implied that masters would serve as “fathers” or “mothers” who would care for their slaves as they would children. This ideology created a way for some slaves to manipulate masters into giving them better treatment, but paternalism always replicated an inequality in power relations and undercut the autonomy of slave families. In a society that so often venerated the authority of men over wives and children, slavery imposed a very different set of expectations on slave men and women.

Though most enslaved women performed field labor similar to their male counterparts, the experience of slavery affected men and women in different ways. Enslaved women were particularly vulnerable to sexual violence. Harriet Jacobs, an enslaved woman from North Carolina, chronicled her master’s attempts to sexually abuse her in her narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Jacobs suggested that her successful attempts to resist sexual assault and her determination to love whom she pleased was “something akin to freedom.” Jacobs’ ability to choose her own lover and spouse was unfortunately not possible for many enslaved women. Rape of slave women was common and could even be used by white men to terrorize both enslaved men and women. Women constantly faced the threat of sexual violence, and multiple accounts exist of men forced to watch as masters raped their wives or children. An absence of laws addressing the rape of slaves allowed for the constant barrage of sexual assault. One enslaved woman from Missouri, Celia, murdered her master after he raped her repeatedly for five years. The rape was overlooked in the courtroom, and Celia was hanged for the murder.

White women and enslaved women were both subject to the authority of white men, yet this did not mean that white women were particularly sympathetic to slaves. White women frequently inflicted physical violence upon their slaves, particularly women, who often worked in close proximity to the household. This type of abuse constituted another way of asserting power within the household. Harriet Jacobs noted that once news of her master’s intentions to sexually exploit her became clear, her mistress became increasingly distrustful of Jacobs, and Jacobs feared for her life.

Slaves could and did resist those who sought to exploit them, both through minor acts of everyday resistance and through organized rebellions. On the morning of August 22, 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia, Nat Turner and six collaborators attempted to free the region’s enslaved population. Turner initiated the violence by killing his master with an axe blow to the head. By the end of the day, Turner and his band, which had grown to over fifty men, killed fifty-seven white men, women, and children on eleven farms. By the next day, the local militia and white residents had captured or killed all of the participants except Turner, who hid for a number of weeks in nearby woods before being captured and executed.

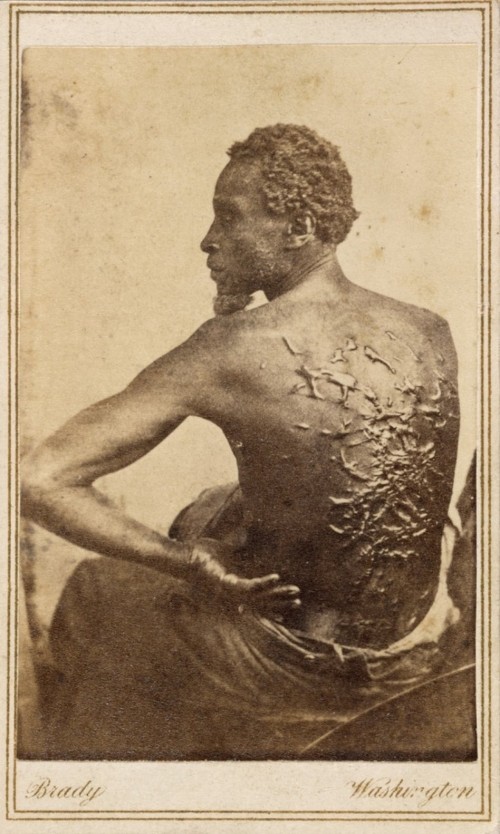

Gordon, the slave pictured here, endured terrible brutality from his master before escaping to Union Army lines in 1863. He would become a soldier and help fight to end the violent system that produced the horrendous scars on his back. Matthew Brady, Gordon, 1863. Wikimedia.

Turner’s rebellion revived white anxieties about a massive slave uprising, fearing the United States would fall to the same fate as Haiti some years earlier. In response to the rebellion, white Virginians cracked down on the state’s African American population. Hundreds of enslaved and free blacks were arrested, deported, or executed, regardless of their involvement in the uprising. Virginia’s legislature passed new restrictions on the free black population—particularly on their interstate mobility—believing that they could be a negative influence on what they believed was an otherwise contented slave population.

Many whites denied that enslaved people would rebel simply against the inhumanity of slavery itself, instead blaming growing abolitionist sentiment in the North for the uprising. William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator was first published in Boston the year Turner and his men took up arms, and David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World had recently appeared in the hands of black Virginians as well. As in other rare instances of insurrections, whites in Virginia placed the blame for the uprising on outsiders—particularly abolitionists and free blacks—and strengthened their defense of slavery.

Nine years before Turner’s rebellion, fears of widespread slave insurrection shook the South Carolina Lowcountry. According to white authorities, a free black Charleston man by the name of Denmark Vesey had organized enslaved and free black inhabitants with the purpose of staging a bloody revolt. Days before the revolt was to take place, fearful slaves revealed the plot to white authorities, leading to swift retribution. Vesey and some thirty-five other blacks were tried and hanged, and others were sold into slavery in the West Indies. The planned revolt inflamed the racial anxieties of whites in Charleston and throughout the South Carolina Lowcountry. In response to the conspiracy, the legislature passed new laws restricting manumission and the mobility of free blacks and created a new guard to protect Charleston against future insurrections.

In recent years, some historians have begun to doubt the commonly accepted Vesey story. Historian Michael P. Johnson in particular has questioned whether a conspiracy existed at all, suggesting it may have been a fabrication of white authorities for their use as a political issue. Most historians continue to believe Vesey was involved in some kind of insurrection plot in the summer of 1822, but the scope and scale of the rebellion remains under debate. Like other southern slave insurrections both real and imagined, the prospect of black-on-white violence stoked the racial fears of many white southerners.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike