In his inaugural address, Lincoln declared secession “legally void.” While he did not intend to invade Southern states, he would use force to maintain possession of federal property within seceded states. Union forces, led by U.S. Army Major Robert Anderson, held Charleston, South Carolina’s Ft. Sumter in April 1861. The fort was in need of supplies, and Lincoln intended to resupply it. South Carolina called for U.S. soldiers to evacuate the fort. Major Anderson refused. “The firing on that fort will inaugurate a civil war greater than any the world has yet seen…you will lose us every friend at the North. You will wantonly strike a hornet’s nest which extends from mountains to ocean. Legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary. It puts us in the wrong. It is fatal,” cautioned Georgia senator Robert Toombs to Jefferson Davis prior to an attack on Fort Sumter. Afterdecades of sectional tension, official hostilities erupted on April 12, 1861, when Confederate Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard fired on the fort. Anderson surrendered on April 13th and the Union troops evacuated. In response to the Confederate attack, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. The American Civil War had begun.

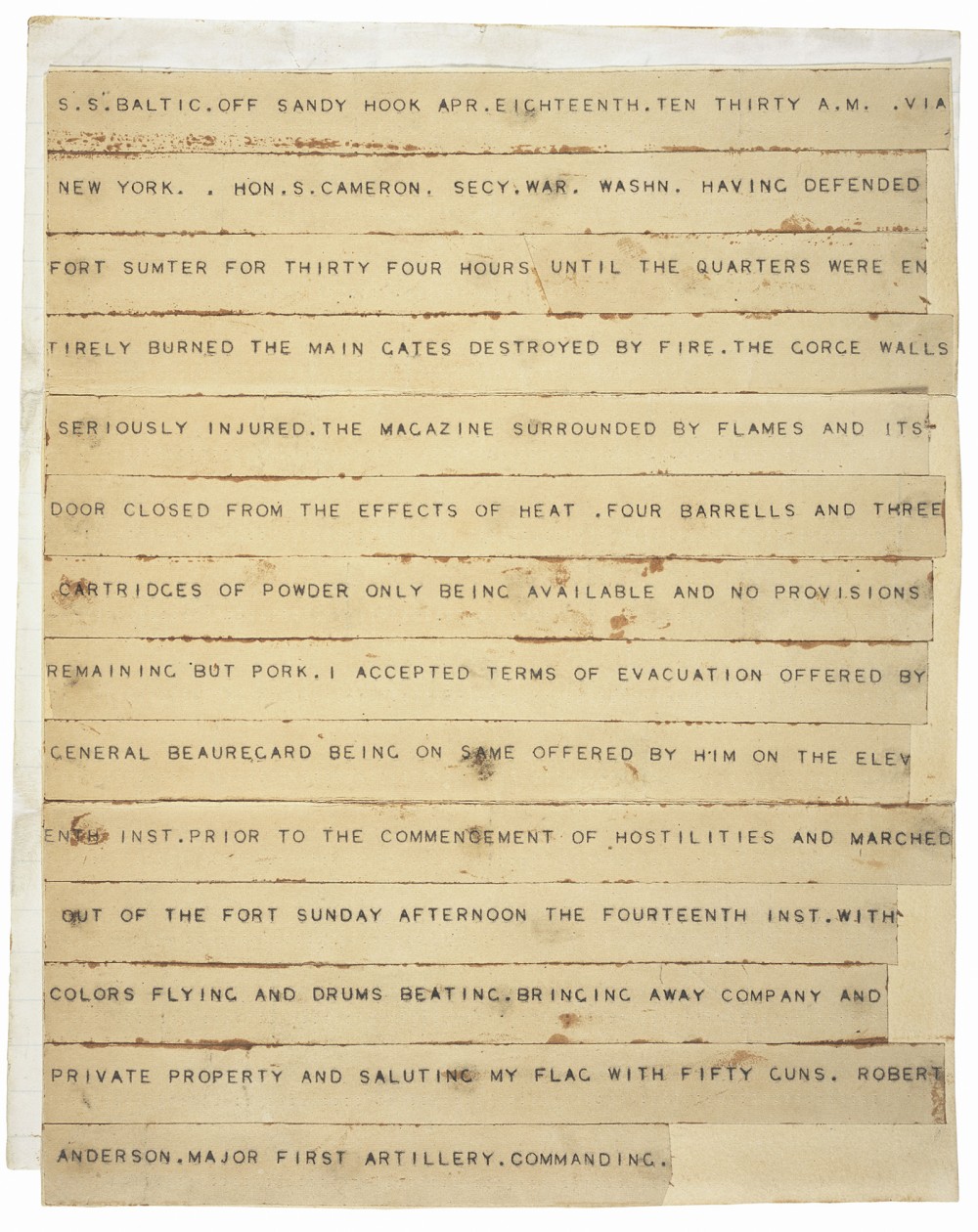

Sent to then Secretary of War Simon Cameron on April 13, 1861, this telegraph announced that after “thirty hours of defending Fort Sumter, Major Robert Anderson had accepted the evacuation offered by Confederate General Beauregard. The Union had surrendered Fort Sumter, and the Civil War had officially begun. “Telegram from Maj. Robert Anderson to Hon. Simon Cameron, Secretary, announcing his withdrawal from Fort Sumter,” April 18, 1861; Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917; Record Group 94; National Archives.

The assault on Fort Sumter, and subsequent call for troops, provoked the Upper South into alliance with the Confederacy. In total, eleven states joined the new nation. Unionists refused to accept this new southern nation and responded with a vigorous military campaign to reduce its armies, property, and economy.

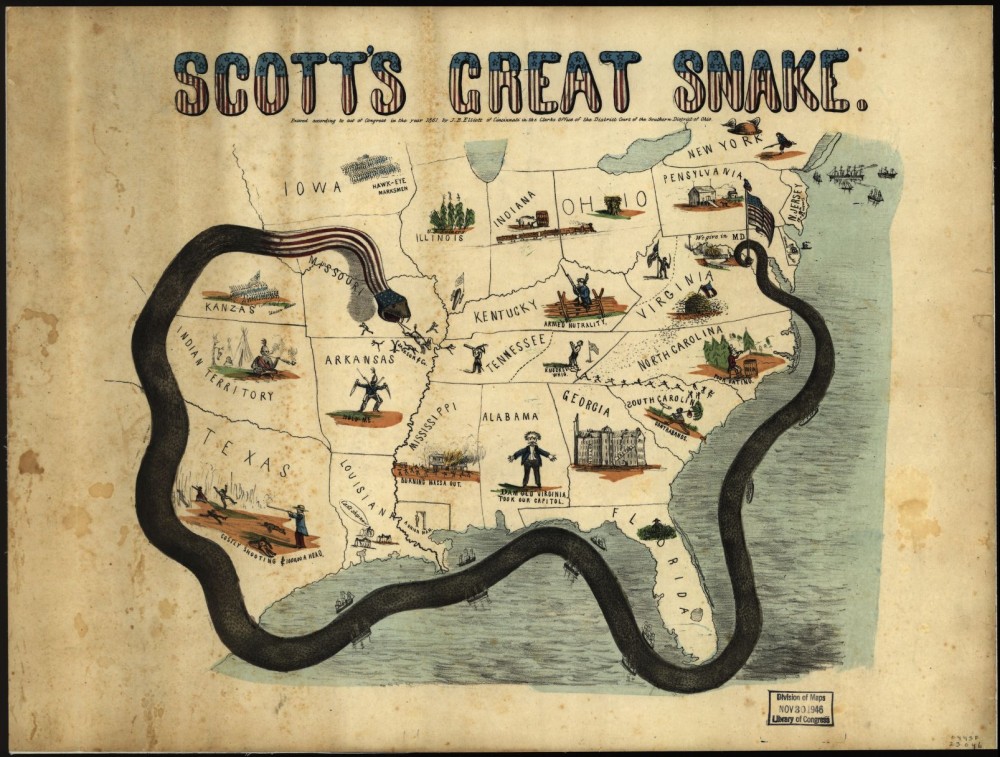

Shortly after Lincoln’s call for troops, the Union adopted General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan and established a naval blockade around the Confederate states. This strategy intended to strangle the Confederacy by cutting off access to coastal ports and inland waterways. Like an anaconda snake, they planned to surround and squeeze the Confederacy.

Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan meant to slowly squeeze the South dry of its resources, blocking all coastal ports and inland waterways to prevent the importation of goods or the export of cotton. This print, while poorly drawn, does a great job of making clear the Union’s plan. J.B. Elliott, “Scott’s great snake. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1861,” 1861. Library of Congress.

With geographic, social, political, and economic connections to both the North and the South, the Border States—Delaware, Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky—were critical to the outcome of the war. Lincoln and his military advisors realized that the loss of the Border States could mean a significant decrease in Union resources. Consequently, Lincoln hoped to foster loyalty among their citizens, so that Union forces could minimize their occupation in the regions. In spite of terrible guerrilla warfare in Missouri and Kentucky, the four Border States remained loyal to the Union throughout the war.

Also that spring, Confederate strategists, like their Federal counterparts, prepared for what they believed would be a short war. This belief crumbled on July 21, 1861. Three months after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Union and Confederate forces met at the Battle of Bull Run, near Manassas, Virginia, officially opening the war’s Eastern Theater. While not particularly deadly, the Confederate victory proved that the Civil War would be long and costly. Furthermore, in response to the embarrassing Union rout, Lincoln removed Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell of command and promoted Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan to commander of the newly formed Army of the Potomac. For nearly a year after the First Battle of Bull Run, the Eastern Theater remained relatively silent. Skirmishes only resulted in a bloody stalemate. Unlike the First Battle of Bull Run, ensuing campaigns resulted in major casualties.

Union military leaders sought to expand the war into the West in hopes of crushing the rebellion. In February 1862, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s capture of Confederate Forts Henry and Donelson along the Tennessee River marked the opening of the Western Theater. Fighting in the West greatly differed from that in the East. At the First Battle of Bull Run, for example, two large armies fought for control of the nations’ capitals; while in the West, Union and Confederate forces fought for control of the rivers, since the Mississippi River and its tributaries were a key tenet of the Union’s Anaconda Plan. One of the deadliest of these clashes occurred along the Tennessee River at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862. This battle, lasting only two days, was the costliest single battle in American history up to that time. The Union victory shocked both the Union and the Confederacy with approximately 23,000 casualties, a number that exceeded casualties from all of the United States’ previous wars combined.

In the fall of that year, casualty numbers would again shock the nation as Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia invaded Maryland (a border state loyal to the Union) on September 3, 1862. Emboldened by their success in the previous spring and summer, Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis planned to win a decisive victory in Union territory and end the war. On September 17, 1862, McClellan and Lee’s forces collided at the Battle of Antietam near the town of Sharpsburg. This battle was the first major battle of the Civil War to occur on Union soil and it remains the bloodiest single day in American history with over 20,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing in just twelve hours.

Photography captured the horrors of war as never before. Some Civil War photographers arranged the actors in their frames to capture the best picture, even repositioning bodies of dead soldiers for battlefield photos. Alexander Gardner, “[Antietam, Md. Confederate dead by a fence on the Hagerstown road],” September 1862. Library of Congress.

Despite the Confederate withdrawal and the high death toll, the Battle of Antietam was not a decisive Union victory. It did, however, result in two significant events. First, McClellan’s failure to crush Lee resulted in his removal. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside replaced McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Second, and more importantly, the Confederate withdrawal gave Lincoln the confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all the slaves in the ten states in rebellion. Framing it as a war measure, Lincoln and his Cabinet hoped that stripping the Confederacy of their labor force would not only debilitate the Southern economy, but also weaken Confederate morale. Nevertheless, Confederates continued fighting; and Union and Confederate forces clashed again at Fredericksburg, Virginia in December 1862. The Battle of Fredericksburg was a Confederate victory that resulted in staggering Union casualties.

Following their success at Fredericksburg, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia continued its offensive strategy in the East. One of the war’s major battles occurred near the village of Chancellorsville, Virginia between April 30 and May 6, 1863. While the Battle of Chancellorsville was an outstanding Confederate victory against Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker (who replaced Burnside as the commander of the Army of the Potomac after his defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg), it also resulted in heavy casualties and the mortal wounding of Major General “Stonewall” Jackson.

In spite of Jackson’s death, Lee continued his offensive against Federal forces and invaded Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863. During the three-day battle (July 1-3) at Gettysburg, heavy casualties crippled both sides. Yet, the devastating July 3 infantry assault on the Union center, also known as Pickett’s Charge, caused Lee to retreat from Pennsylvania. The Gettysburg Campaign was Lee’s final northern incursion and the Battle of Gettysburg remains as the bloodiest battle of the war, and in American history, with 51,000 casualties.

Concurrently in the West, Union forces continued their movement along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, capturing New Orleans on May 1, 1862. With New Orleans occupied and with help from the U. S. Navy, Grant launched his campaign against Vicksburg, Mississippi in the winter of 1862. His Vicksburg Campaign, which lasted until July 4, 1863, ended with the city’s surrender and split the Confederacy in two.

The Union and Confederate navies helped or hindered army movements around the many marine environments of the southern United States. And each navy employed the latest technology to outmatch the other. The Confederate Navy, led by Stephen Russell Mallory, had the unenviable task of constructing a fleet from scratch and trying to fend off a vastly better equipped Union Navy. Led by Gideon Welles of Connecticut, the Union Navy successfully implemented General-in-Chief Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan.

The Union blockade initially struggled to contain the Confederate blockade runners, especially at ports like Charleston, South Carolina and Wilmington, North Carolina. The blockade was not particularly effective until halfway through the war. Major Confederate ports and financial trade centers, including those on the Mississippi River like New Orleans, had come under Union control by mid-1863.

Grant’s successes at Vicksburg and Chattanooga, Tennessee (November 1863) and Meade’s cautious pursuit of Lee after Gettysburg prompted Lincoln to promote Grant to general-in-chief of the Union Army in early 1864. This change in command not only allowed for Grant’s second-in-command, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to launch his infamous March to the Sea, in which his men devastated Georgia and the Carolinas, but it also resulted in some of the bloodiest battles of the Eastern Theater. These battles, such as the Battle of the Wilderness, the Battle of Cold Harbor, and the siege of Petersburg, as part of Grant’s Overland Campaign would earn Grant his nickname “The Butcher.”

New and more destructive warfare technology emerged during this time that utilized discoveries and innovations in other areas of life, like transportation. This photograph shows Robert E. Lee’s railroad gun and crew used in the main eastern theater of war at the siege of Petersburg, June 1864-April 1865. “Petersburg, Va. Railroad gun and crew,” between 1864 and 1865. Library of Congress.

Incredibly deadly for both sides, these Union campaigns in both the West and the East, destroyed Confederate infrastructure and demonstrated the efficacy of the Union’s strategy of attrition and hard war. As a result of Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” a devastating hard war campaign through Georgia and the Carolinas, and Grant’s dogged pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. The remaining Confederate forces surrendered that summer.

Unions soldiers pose in front of the Appomattox Court House after Lee’s surrender in April 1865. Wikimedia.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike