California, belonging to Mexico prior to the war, was at least three arduous months travel from the nearest American settlements. While missionaries made the trip more frequently, there was some sparse settlement in the Sacramento valley. The fertile farmland of Oregon, like the black dirt lands of the Mississippi valley, attracted more settlers than California.

Exacerbating concerns was the presence of often over-dramatized stories of Indian attack that filled migrants with a sense of foreboding, although the majority of settlers encouraged nonviolence and often no Indians at all. The slow progress, disease, human and oxen starvation, poor trails, terrible geographic preparations, lack of guidebooks, threatening wildlife, vagaries of weather, and general confusion were all more formidable and regular challenges than Indian attack. Despite the harshness of the journey, by 1848 there were approximated 20,000 Americans living west of the Rockies, with about three-fourths of that number in Oregon.

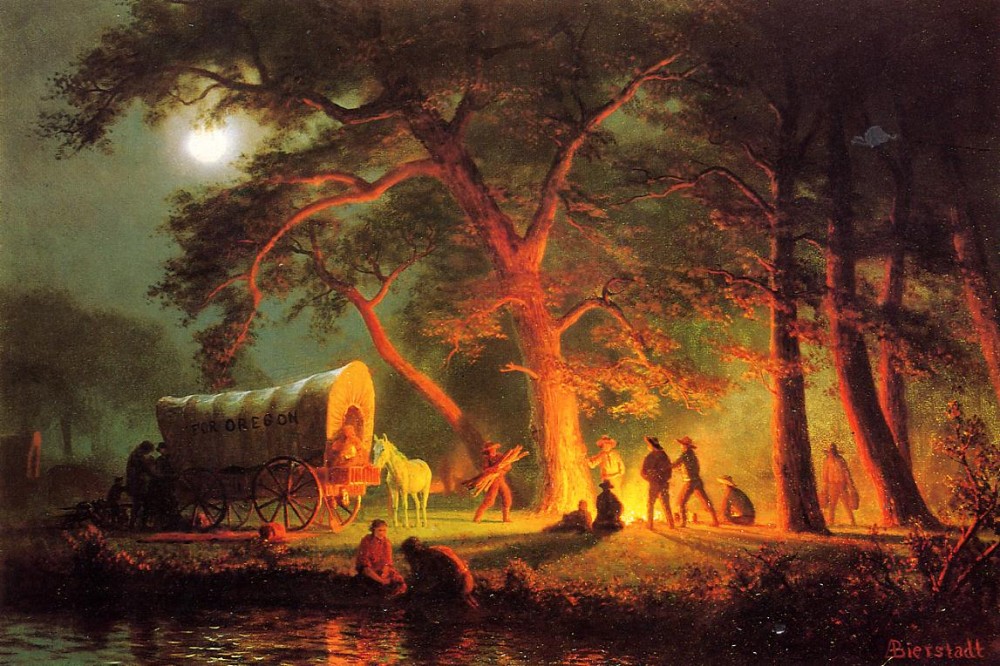

The great environmental and economic potential of the Oregon Territory led many to pack up their families and head west along the Oregon Trail. The Trail represented the hopes of many for a better life, represented and reinforced by images like Bierstadt’s idealistic Oregon Trail. In reality, the Trail was violent and dangerous, and many who attempted to cross never made it to the “Promised Land” of Oregon. Albert Bierstadt, Oregon Trail (Campfire), 1863. Wikimedia.

The lure and imagination of the West lured many migrants to the far west. However, those with the adventuring spirit and stomach were modest. Many who moved sought the reflection of what they believed themselves to be in the great untamed lands of the West. The romantic vision of life west of the Mississippi attracted a certain breed of Americans. The rugged individualism and martial prowess of the West and the Mexican war was the first spark that drew a new breed different than the modest agricultural communities of the near-west.

If the great draw of the West stood as manifest destiny’s kindling then the discovery of gold in California was the spark the set that fire ablaze. The strongest driving forces of Manifest Destiny lay in the somewhat coordinated movement of settlers via trails (slave-based, subsistence agriculture, and religious), the military (War with Mexico and American Indians, filibustering adventures), and political focus (the expansion of slavery, Compromise of 1850) toward the western territory added to the United States. Undoubtedly, while the vast majority of those leaving the Eastern seaboard and old Mississippi valley frontier via the wagon trails sought land ownership, the lure of getting rich quick drew a not unsizable portion of the migration’s primarily younger single male participants (with some women) to gold towns throughout the West. These core constituencies of adventures and fortune-seekers then served as magnets for the arrival of corresponding providers of services associated with the gold rush. The rapid growth of towns and cities throughout the West, notably San Francisco whose population grew from about 500 in 1848 to almost 50,000 by 1853, and the seemingly endless possibility for individual success in all matters of pursuit put a positive economic spin on the tenets of manifest destiny. Yet, the lawlessness, predictable failure of most fortune seekers, conflicts with native populations of the area – including Mexican, Spanish, American Indian, Chinese, and Japanese populations – and the explosion of the slavery question all demonstrated the downside of Manifest Destiny’s promise. The gold rush sped up the already quickening political march to the Pacific.

On January 24, 1848 James W. Marshall, a contractor hired by John Sutter, discovered gold on Sutter’s sawmill land in the Sacramento valley area of the then territory of California. The agitation of the territory’s relatively small American population, much like Texas before it, attracted substantial U.S. military effort in aid of some American forces already there at the onset of the Mexican war. Encouragement of westward migration was as much an individual economic imperative as it was a national defense necessity. The discovery of gold did much to solve at least one of those issues as the integration of the quickly populated state California, and with it the vital port of San Francisco, augmented American strength and national economic grounding. Throughout the 1850s, Californians beseeched Congress for a transcontinental railroad to provide service for both passengers and goods from the Midwest and the East Coast. The potential economic benefits for communities along proposed railroads made the debate over the railroad’s route rancorous and overlapped on top of growing dissent over the slavery issue. For their part, the economic boom ushered in by the gold rush allowed the state government of California to begin work on a state rail system in the Sacramento Valley in 1854.

The great influx of people and the great diversity on display, encased in a combative and aggrandizing atmosphere of individualistic pursuit of fortune, produced all sorts of antagonisms. Linguistic, cultural, economic, and racial conflict roiled both urban and rural areas. By the end of the 1850s, Chinese and Mexican immigrants made up 1/5th of the mining population in California mining towns. The competition for land, resources, and riches furthered individual and collective abuses particularly against American Indians and the older Mexican communities and missions established before statehood. California’s towns, as well as those dotting the landscape throughout the West, struggled to balance security with economic development and the protection of civil rights and liberties.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike