In 1862, a New York Herald reporter wrote that “All history proves that music is as indispensable to warfare as money; and money has been called the sinews of war.” Music was popular among the soldiers of both armies, creating a diversion from the boredom and horror of the war. As a result, soldiers often sang on fatigue duty and while in camp. Favorite songs, including “Lorena,” “Home, Sweet Home,” and “Just Before the Battle, Mother,” often reminded the soldiers of home. Dances held in camp offered another way to enjoy music. Since there were often very few women nearby, soldiers would dance with one another.

When the Civil War broke out, one of the most popular songs among soldiers and civilians was “John Brown’s Body” which began “John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave.” Started as a Union anthem praising John Brown’s actions at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, then used by Confederates to vilify Brown, both sides’ version of the song stressed that they were on the right side. Eventually the words to Julia Ward Howe’s poem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” were set to the melody, further implying Union success.

Music was intrinsic to both soldiers’ and civilians’ lives throughout the war. In 1863, “When This Cruel War Is Over,” sometimes referred to by part of its chorus, “weeping, sad and lonely,” became popular as both soldiers and civilians recognized the probability that they would never see their loved ones again. Referring to the “lonely, wounded, even dying, calling but in vain,” the song dwelled on battlefield horrors, causing some commanders to restrict its use. The themes of popular songs changed over the course of the war, as feelings of inevitable success alternated with feelings of terror and despair.

Disease haunted both armies, and accounted for over half of all Civil War casualties. Sometimes as many as half of the men in a company could be sick. The overwhelming majority of Civil War soldiers came from rural areas, where there was less exposure to diseases, meaning that these soldiers lacked immunities. Vaccines for diseases such as smallpox were largely unavailable to those not in cities or towns. Despite the common nineteenth-century tendency to see city-men as weak or soft, soldiers from urban environments tended to succumb to fewer diseases than their rural counterparts. Tuberculosis, measles, rheumatism, typhoid, malaria, and smallpox spread almost unchecked among the armies.

Civil War medicine focused almost exclusively on curing the patient rather than preventing disease. Many soldiers attempted to cure themselves by concocting elixirs and medicines themselves. These ineffective “home-remedies” were often made from various plants the men found in woods or fields. There was no understanding of germ theory so many soldiers did things that we would consider unsanitary today. They ate food that was improperly cooked and handled, and practiced what we would consider poor personal hygiene. They didn’t take appropriate steps to ensure that the water they drank was free from bacteria. Diarrhea and dysentery were common. These diseases were especially dangerous, as Civil War soldiers did not understand the value of replacing fluids as they were lost. As such, men affected by these conditions would weaken, and become unable to fight or march, and as they became dehydrated their immune system became less effective, inviting other infections to attack the body.

Through trial and error soldiers began to protect themselves from some of the more preventable sources of infection. Around 1862 both armies began to dig latrines rather than rely upon the local waterways. Burying human and animal waste cut down on exposure to diseases considerably.

Medical surgery was limited and brutal. If a soldier was wounded in the torso, throat, or head there was little surgeons could do. Invasive procedures to repair damaged organs or stem blood loss invariably resulted in death. Luckily for soldiers, only approximately one-in-six combat wounds were to one of those parts. The remaining were to limbs, which was treatable by amputation. Soldiers had the highest chance of survival if the limb was removed within 48 hours of injury. A skilled surgeon could amputate a limb around three to five minutes from start to finish. While the lack of germ theory again caused several unsafe practices, such as using the same tools on multiple patients, wiping hands on filthy gowns, or placing hands in communal buckets of water, there is evidence that amputation offered the best chance of survival.

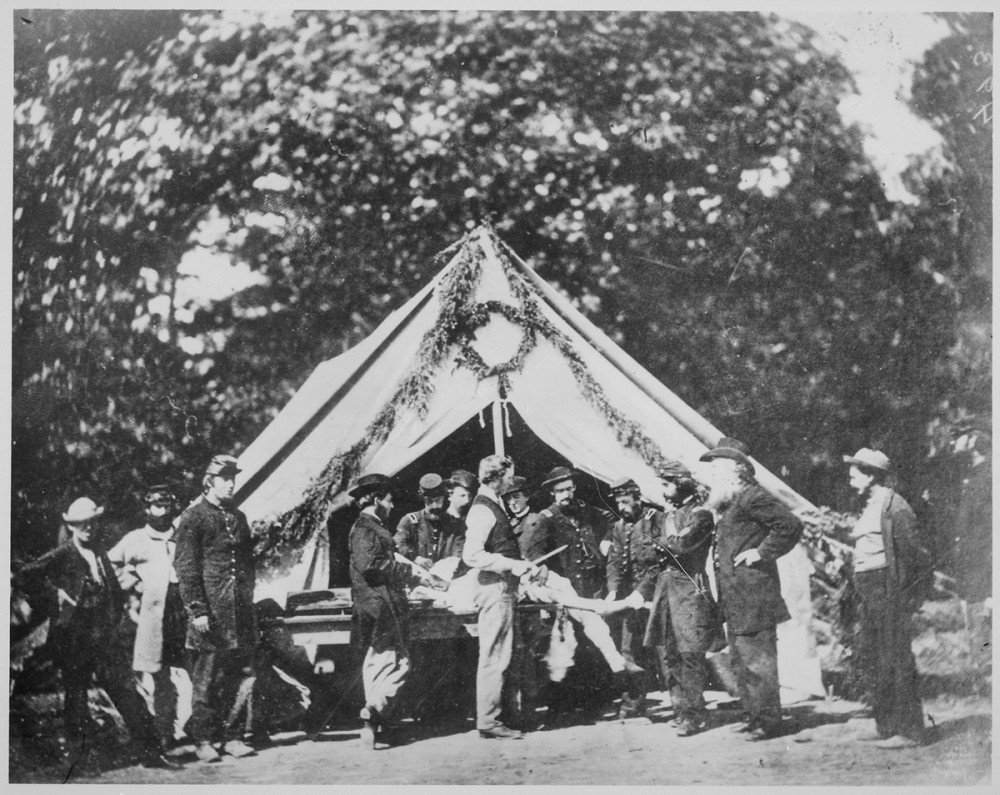

Amputations were a common form of treatment during the war. While it saved the lives of some soldiers, it was extremely painful and resulted in death in many cases. It also produced the first community of war veterans without limbs in American history. “Amputation being performed in a hospital tent, Gettysburg,” July 1863. National Archives and Records Administration.

It is a common misconception that amputation was accompanied without anesthesia and against a patient’s wishes. Since the 1830s Americans understood the benefits of Nitrous Oxide and Ether on easing pain. Chloroform and opium were also used to either render patients unconscious or to dull pain during the procedure. Also, surgeons would not amputate without the patient’s consent.

In the Union army alone, 2.8 million ounces of opium and over 5.2 million opium pills were administered. In 1862 William Alexander Hammon was appointed Surgeon General for the US. He sought to regulate dosages and manage supplies of available medicines, both to prevent overdosing and to ensure that an ample supply remained for the next engagement. However, his guidelines tended to apply only to the regular federal army. The majority of Union soldiers were in volunteer units and organized at the state level. Their surgeons often ignored posted limits on medicines, or worse experimented with their own concoctions made from local flora.

Death came in many forms—disease, prisons, bullets, even lightning and bee stings, took men slowly or suddenly. Their deaths, however, affected more than their regiments. Before the war, a wife expected to sit at her husband’s bed, holding his hand, and ministering to him after a long, fulfilling life. This type of death, the Good Death, changed during the Civil War as men died often far from home among strangers. Casualty reporting was inconsistent, so women were often at the mercy of the men who fought alongside her husband to learn not only the details of his death, but even that the death had occurred.

“Now I’m a widow. Ah! That mournful word. Little the world think of the agony it contains!” wrote Sally Randle Perry in her diary. After her husband’s death at Sharpsburg, Sally received the label of she would share with more than 200,000 other white women. The death of a husband and loss of financial, physical, and emotional support could shatter lives. It also had the perverse power to free women from bad marriages and open doors to financial and psychological independence.

Widows had an important role to play in the conflict. The ideal widow wore black, mourned for a minimum of two and a half years, resigned herself to God’s will, focused on her children, devoted herself to her husband’s memory, and brought his body home for burial. Many tried, but not all widows were able to live up to the ideal. Many were unable to purchase proper mourning garb. Silk black dresses, heavy veils, and other features of antebellum mourning were expensive and in short supply. Because most of these women were in their childbearing years, the war created an unprecedented number of widows who were pregnant or still nursing infants. In a time when the average woman gave birth to eight to ten children in her lifetime, it is perhaps not surprising that the Civil War created so many widows who were also young mothers with little free time for formal mourning.

Widowhood permeated American society. But in the end, it was up to each widow to navigate her own mourning. She joined the ranks of sisters, mothers, cousins, girlfriends, and communities in mourning men.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike