More than five million immigrants arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1860. Irish, German, and Jewish immigrants sought new lives and economic opportunities. By the Civil War, nearly one out of every eight Americans had been born outside of the United States. A series of push and pull factors drew immigrants to the United States.

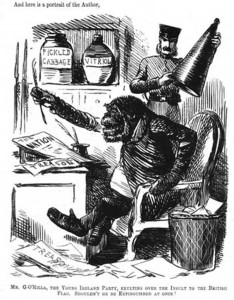

In England, an economic slump prompted Parliament to modernize British agriculture by revoking common land rights for Irish farmers. These policies generally targeted Catholics in the southern counties of Ireland and motivated many to seek greater opportunity and the booming American economy pulled Irish immigrants towards ports along the eastern United States. Between 1820 and 1840, over 250,000 Irish immigrants arrived in the United States. Without the capital and skills required to purchase and operate farms, Irish immigrants settled primarily in northeastern cities and towns and performed unskilled work. Irish men usually emigrated alone and, when possible, practiced what became known as chain migration. Chain migration allowed Irish men to send portions of their wages home, which would then be used to either support their families in Ireland or to purchase tickets for relatives to come to the United States. Irish immigration followed this pattern into the 1840s and 1850s, when the infamous Irish Famine sparked a massive exodus out of Ireland. Between 1840 and 1860, 1.7 million Irish fled starvation and the oppressive English policies that accompanied it. As they entered manual, unskilled labor positions in urban America’s dirtiest and most dangerous occupations, Irish workers in northern cities were compared to African Americans and nativist newspapers portrayed them with ape-like features. Despite hostility, Irish immigrants retained their social, cultural, and religious beliefs and left an indelible mark on American culture.

John Tenniel, “Mr. G’Orilla,” c. 1845-52, via Wikimedia.

While the Irish settled mostly in coastal cities, most German immigrants used American ports and cities as temporary waypoints before settling in the rural countryside. Over 1.5 million immigrants from the various German states arrived in the United States during the antebellum era. Although some southern Germans fled declining agricultural conditions and repercussions of the failed revolutions of 1848, many Germans simply sought steadier economic opportunity. German immigrants tended to travel as families and carried with them skills and capital that enabled them to enter middle class trades. Germans migrated to the Old Northwest to farm in rural areas and practiced trades in growing communities such as St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Milwaukee, three cities that formed what came to be called the German Triangle.

Most German immigrants were Catholics, but many were Jewish. Although records are sparse, New York’s Jewish population rose from approximately 500 in 1825 to 40,000 in 1860. Similar gains were seen in other American cities. Jewish immigrants, hailing from southwestern Germany and parts of occupied Poland, moved to the United States through chain migration and as family units. Unlike other Germans, Jewish immigrants rarely settled in rural areas. Once established, Jewish immigrants found work in retail, commerce, and artisanal occupations such as tailoring. They quickly found their footing and established themselves as an intrinsic part of the American market economy. Just as Irish immigrants shaped the urban landscape through the construction of churches and Catholic schools, Jewish immigrants erected synagogues and made their mark on American culture.

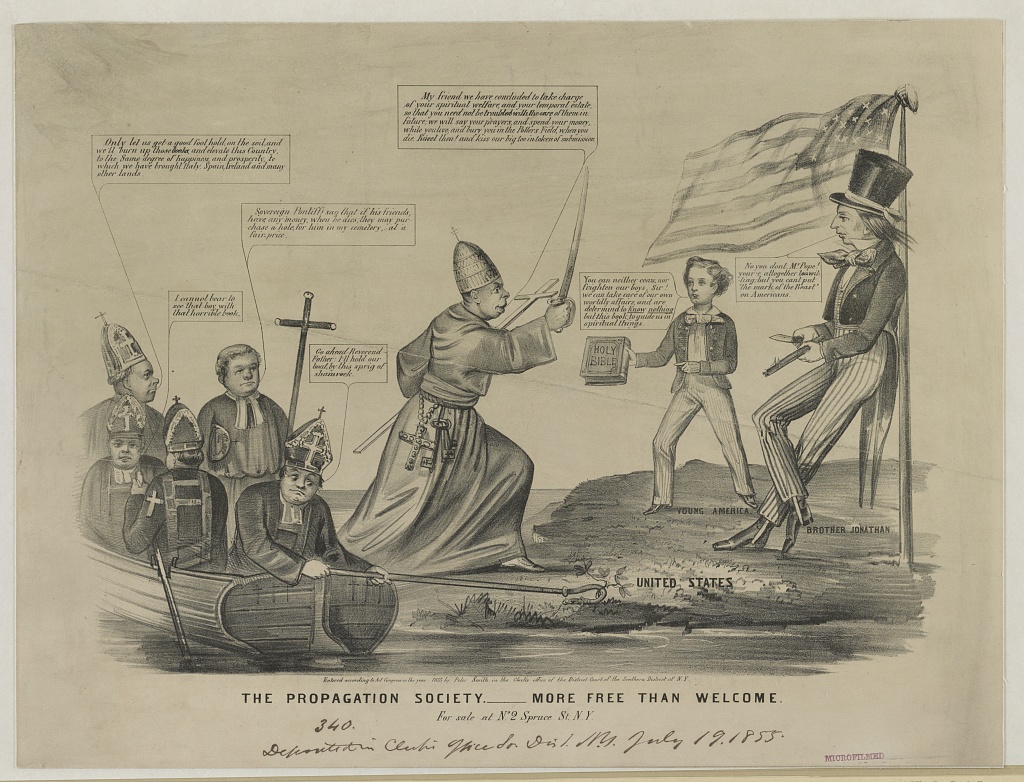

The sudden influx of immigration triggered a backlash among many native-born Anglo-Protestant Americans. This nativist movement, especially fearful of the growing Catholic presence, sought to limit European immigration and prevent Catholics from establishing churches and other institutions. Popular in northern cities such as Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other cities with large Catholic populations, nativism even spawned its own political party in the 1850s. The American Party, more commonly known as the “Know-Nothing Party,” found success in local and state elections throughout the North. The party even nominated candidates for President in 1852 and 1856. The rapid rise of the Know-Nothings, reflecting widespread anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment, slowed European immigration. Immigration declined precipitously after 1855 as nativism, the Crimean War, and improving economic conditions in Europe discouraged potential migrants from traveling to the United States. Only after the American Civil War would immigration levels match, and eventually surpass, the levels seen in the 1840s and 1850s.

In industrial northern cities, Irish immigrants swelled the ranks of the working class and quickly encountered the politics of industrial labor. Many workers formed trade unions during the early republic. Organizations such as the Philadelphia’s Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers or the Carpenters’ Union of Boston operated in within specific industries in major American cities and worked to protect the economic power of their members by creating closed shops—workplaces wherein employers could only hire union members—and striking to improve working conditions. Political leaders denounced these organizations as unlawful combinations and conspiracies to promote the narrow self-interest of workers above the rights of property holders and the interests of the common good. Unions did not become legally acceptable—and then only haltingly—until 1842 when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of a union organized among Boston bootmakers, arguing that the workers were capable of acting “in such a manner as best to subserve their own interests.”

N. Currier, “The Propagation Society, More Free than Welcome,” 1855, via Wikimedia.

In the 1840s, labor activists organized to limit working hours and protect children in factories. The New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workingmen (NEA) mobilized to establish a ten-hour day across industries. They argued that the ten-hour day would improve the immediate conditions of laborers by allowing “time and opportunities for intellectual and moral improvement.” After a city-wide strike in Boston in 1835, the Ten-Hour Movement quickly spread to other major cities such as Philadelphia. The campaign for leisure time was part of the male working-class effort to expose the hollowness of the paternalistic claims of employers and their rhetoric of moral superiority.

Women, a dominant labor source for factories since the early 1800s, launched some of the earliest strikes for better conditions. Textile operatives in Lowell, Massachusetts, “turned-out” (walked off) their jobs in 1834 and 1836. During the Ten-Hour Movement of the 1840s, female operatives provided crucial support. Under the leadership of Sarah Bagley, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association organized petition drives that drew thousands of signatures from “mill girls.” Like male activists, Bagley and her associates used the desire for mental improvement as a central argument for reform. An 1847 editorial in the Voice of Industry, a labor newspaper published by Bagley, asked “who, after thirteen hours of steady application to monotonous work, can sit down and apply her mind to deep and long continued thought?” Despite the widespread support for a ten-hour day, the movement achieved only partial success. President Van Buren established a ten-hour-day policy for laborers on federal public works projects. New Hampshire passed a state-wide law in 1847 and Pennsylvania following a year later. Both states, however, allowed workers to voluntarily consent to work more than ten hours per day.

In 1842, child labor became a dominant issue in the American labor movement. The protection of child laborers gained more middle-class support, especially in New England, than the protection of adult workers. A petition from parents in Fall River, a southern Massachusetts mill town that employed a high portion of child workers, asked the legislature for a law “prohibiting the employment of children in manufacturing establishments at an age and for a number of hours which must be permanently injurious to their health and inconsistent with the education which is essential to their welfare.” Massachusetts quickly passed a law prohibiting children under the age of twelve from working more than ten hours a day. By the mid-nineteenth century, every state in New England had followed Massachusetts’ lead. Between the 1840s and 1860s, these statutes slowly extended the age of protection of labor and the assurance of schooling. Throughout the region, public officials agreed that young children (between nine and twelve years) should be prevented from working in dangerous occupations, and older children (between twelve and fifteen years) should balance their labor with education and time for leisure.

Male workers, sought to improve their income and working conditions to create a household that kept women and children protected within the domestic sphere. But labor gains were limited and movement itself remained moderate. Despite its challenge to industrial working conditions, labor activism in antebellum America remained largely wedded to the free labor ideal. The labor movement supported the northern free soil movement, which challenged the spread of slavery, that emerged during the 1840s, simultaneously promoting the superiority of the northern system of commerce over the southern institution of slavery while trying, much less successfully, to reform capitalism.

Candela Citations

- American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. Project: American Yawp. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike