Summarize the roles carbohydrates play in biological systems

Are carbohydrates good for you? People who wish to lose weight are often told that carbohydrates are bad for them and should be avoided. Some diets completely forbid carbohydrate consumption, claiming that a low-carbohydrate diet helps people to lose weight faster. However, carbohydrates have been an important part of the human diet for thousands of years; artifacts from ancient civilizations show the presence of wheat, rice, and corn in our ancestors’ storage areas.

Carbohydrates should be supplemented with proteins, vitamins, and fats to be parts of a well-balanced diet. Calorie-wise, a gram of carbohydrate provides 4.3 Kcal. For comparison, fats provide 9 Kcal/g, a less desirable ratio. Carbohydrates contain soluble and insoluble elements; the insoluble part is known as fiber, which is mostly cellulose. Fiber has many uses; it promotes regular bowel movement by adding bulk, and it regulates the rate of consumption of blood glucose. Fiber also helps to remove excess cholesterol from the body. In addition, a meal containing whole grains and vegetables gives a feeling of fullness. As an immediate source of energy, glucose is broken down during the process of cellular respiration, which produces ATP, the energy currency of the cell. Without the consumption of carbohydrates, the availability of “instant energy” would be reduced.

Eliminating carbohydrates from the diet is not the best way to lose weight. A low-calorie diet that is rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and lean meat, together with plenty of exercise and plenty of water, is the more sensible way to lose weight.

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides

- Identify several major functions of carbohydrates

Most people are familiar with carbohydrates, one type of macromolecule, especially when it comes to what we eat. To lose weight, some individuals adhere to “low-carb” diets. Athletes, in contrast, often “carb-load” before important competitions to ensure that they have enough energy to compete at a high level. Carbohydrates are, in fact, an essential part of our diet; grains, fruits, and vegetables are all natural sources of carbohydrates. Carbohydrates provide energy to the body, particularly through glucose, a simple sugar that is a component of starch and an ingredient in many staple foods. Carbohydrates also have other important functions in humans, animals, and plants.

Molecular Structures

Carbohydrates can be represented by the stoichiometric formula (CH2O)n, where n is the number of carbons in the molecule. In other words, the ratio of carbon to hydrogen to oxygen is 1:2:1 in carbohydrate molecules. This formula also explains the origin of the term “carbohydrate”: the components are carbon (“carbo”) and the components of water (hence, “hydrate”). Carbohydrates are classified into three subtypes: monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides.

Monosaccharides

Monosaccharides (mono– = “one”; sacchar– = “sweet”) are simple sugars, the most common of which is glucose. In monosaccharides, the number of carbons usually ranges from three to seven. Most monosaccharide names end with the suffix –ose. If the sugar has an aldehyde group (the functional group with the structure R-CHO), it is known as an aldose, and if it has a ketone group (the functional group with the structure RC(=O)R′), it is known as a ketose. Depending on the number of carbons in the sugar, they also may be known as trioses (three carbons), pentoses (five carbons), and or hexoses (six carbons). See Figure 1 for an illustration of the monosaccharides.

Figure 1. Monosaccharides are classified based on the position of their carbonyl group and the number of carbons in the backbone. Aldoses have a carbonyl group (indicated in green) at the end of the carbon chain, and ketoses have a carbonyl group in the middle of the carbon chain. Trioses, pentoses, and hexoses have three, five, and six carbon backbones, respectively.

The chemical formula for glucose is C6H12O6. In humans, glucose is an important source of energy. During cellular respiration, energy is released from glucose, and that energy is used to help make adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Plants synthesize glucose using carbon dioxide and water, and glucose in turn is used for energy requirements for the plant. Excess glucose is often stored as starch that is catabolized (the breakdown of larger molecules by cells) by humans and other animals that feed on plants.

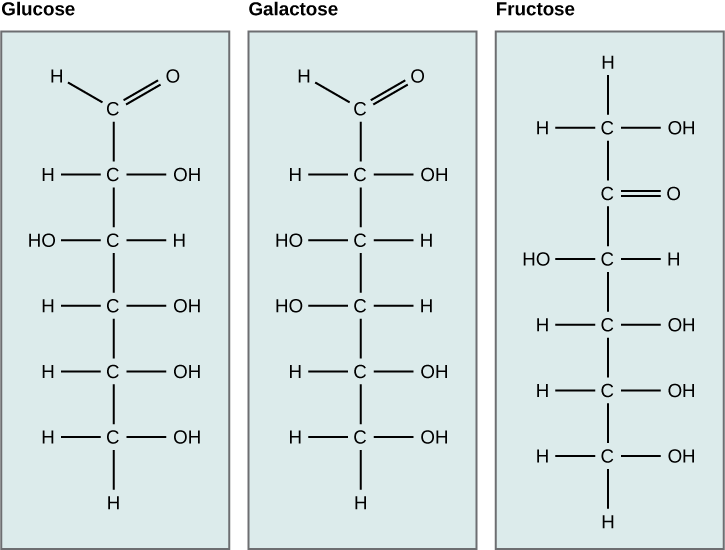

Galactose (part of lactose, or milk sugar) and fructose (part of sucrose, or fruit sugar) are other common monosaccharides. Although glucose, galactose, and fructose all have the same chemical formula (C6H12O6), they differ structurally and chemically (and are known as isomers) because of the different arrangement of functional groups around the asymmetric carbon; all of these monosaccharides have more than one asymmetric carbon (Figure 2).

Practice Question

Figure 2. Glucose, galactose, and fructose are all hexoses. They are structural isomers, meaning they have the same chemical formula (C6H12O6) but a different arrangement of atoms.

What kind of sugars are these, aldose or ketose?

Monosaccharides can exist as a linear chain or as ring-shaped molecules; in aqueous solutions they are usually found in ring forms (Figure 3). Glucose in a ring form can have two different arrangements of the hydroxyl group (−OH) around the anomeric carbon (carbon 1 that becomes asymmetric in the process of ring formation). If the hydroxyl group is below carbon number 1 in the sugar, it is said to be in the alpha (α) position, and if it is above the plane, it is said to be in the beta (β) position.

Figure 3. Five and six carbon monosaccharides exist in equilibrium between linear and ring forms. When the ring forms, the side chain it closes on is locked into an α or β position. Fructose and ribose also form rings, although they form five-membered rings as opposed to the six-membered ring of glucose.

Disaccharides

Disaccharides (di– = “two”) form when two monosaccharides undergo a dehydration reaction (also known as a condensation reaction or dehydration synthesis). During this process, the hydroxyl group of one monosaccharide combines with the hydrogen of another monosaccharide, releasing a molecule of water and forming a covalent bond. A covalent bond formed between a carbohydrate molecule and another molecule (in this case, between two monosaccharides) is known as a glycosidic bond (Figure 4). Glycosidic bonds (also called glycosidic linkages) can be of the alpha or the beta type.

Figure 4. Sucrose is formed when a monomer of glucose and a monomer of fructose are joined in a dehydration reaction to form a glycosidic bond. In the process, a water molecule is lost. By convention, the carbon atoms in a monosaccharide are numbered from the terminal carbon closest to the carbonyl group. In sucrose, a glycosidic linkage is formed between carbon 1 in glucose and carbon 2 in fructose.

Common disaccharides include lactose, maltose, and sucrose (Figure 5). Lactose is a disaccharide consisting of the monomers glucose and galactose. It is found naturally in milk. Maltose, or malt sugar, is a disaccharide formed by a dehydration reaction between two glucose molecules. The most common disaccharide is sucrose, or table sugar, which is composed of the monomers glucose and fructose.

Figure 5. Common disaccharides include maltose (grain sugar), lactose (milk sugar), and sucrose (table sugar).

Polysaccharides

A long chain of monosaccharides linked by glycosidic bonds is known as a polysaccharide (poly– = “many”). The chain may be branched or unbranched, and it may contain different types of monosaccharides. The molecular weight may be 100,000 daltons or more depending on the number of monomers joined. Starch, glycogen, cellulose, and chitin are primary examples of polysaccharides.

Starch is the stored form of sugars in plants and is made up of a mixture of amylose and amylopectin (both polymers of glucose). Plants are able to synthesize glucose, and the excess glucose, beyond the plant’s immediate energy needs, is stored as starch in different plant parts, including roots and seeds. The starch in the seeds provides food for the embryo as it germinates and can also act as a source of food for humans and animals. The starch that is consumed by humans is broken down by enzymes, such as salivary amylases, into smaller molecules, such as maltose and glucose. The cells can then absorb the glucose.

Starch is made up of glucose monomers that are joined by α 1-4 or α 1-6 glycosidic bonds. The numbers 1-4 and 1-6 refer to the carbon number of the two residues that have joined to form the bond. As illustrated in Figure 6, amylose is starch formed by unbranched chains of glucose monomers (only α 1-4 linkages), whereas amylopectin is a branched polysaccharide (α 1-6 linkages at the branch points).

Figure 6. Amylose and amylopectin are two different forms of starch. Amylose is composed of unbranched chains of glucose monomers connected by α 1,4 glycosidic linkages. Amylopectin is composed of branched chains of glucose monomers connected by α 1,4 and α 1,6 glycosidic linkages. Because of the way the subunits are joined, the glucose chains have a helical structure. Glycogen (not shown) is similar in structure to amylopectin but more highly branched.

Glycogen is the storage form of glucose in humans and other vertebrates and is made up of monomers of glucose. Glycogen is the animal equivalent of starch and is a highly branched molecule usually stored in liver and muscle cells. Whenever blood glucose levels decrease, glycogen is broken down to release glucose in a process known as glycogenolysis.

Cellulose is the most abundant natural biopolymer. The cell wall of plants is mostly made of cellulose; this provides structural support to the cell. Wood and paper are mostly cellulosic in nature. Cellulose is made up of glucose monomers that are linked by β 1-4 glycosidic bonds (Figure 7).

Figure 7. In cellulose, glucose monomers are linked in unbranched chains by β 1-4 glycosidic linkages. Because of the way the glucose subunits are joined, every glucose monomer is flipped relative to the next one resulting in a linear, fibrous structure.

As shown in Figure 7, every other glucose monomer in cellulose is flipped over, and the monomers are packed tightly as extended long chains. This gives cellulose its rigidity and high tensile strength—which is so important to plant cells. While the β 1-4 linkage cannot be broken down by human digestive enzymes, herbivores such as cows, koalas, buffalos, and horses are able, with the help of the specialized flora in their stomach, to digest plant material that is rich in cellulose and use it as a food source. In these animals, certain species of bacteria and protists reside in the rumen (part of the digestive system of herbivores) and secrete the enzyme cellulase. The appendix of grazing animals also contains bacteria that digest cellulose, giving it an important role in the digestive systems of ruminants. Cellulases can break down cellulose into glucose monomers that can be used as an energy source by the animal. Termites are also able to break down cellulose because of the presence of other organisms in their bodies that secrete cellulases.

Figure 8. Insects have a hard outer exoskeleton made of chitin, a type of polysaccharide.

Carbohydrates serve various functions in different animals. Arthropods (insects, crustaceans, and others) have an outer skeleton, called the exoskeleton, which protects their internal body parts (as seen in the bee in Figure 8).

This exoskeleton is made of the biological macromolecule chitin, which is a polysaccharide-containing nitrogen. It is made of repeating units of N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamine, a modified sugar. Chitin is also a major component of fungal cell walls; fungi are neither animals nor plants and form a kingdom of their own in the domain Eukarya.

In Summary: Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are a group of macromolecules that are a vital energy source for the cell and provide structural support to plant cells, fungi, and all of the arthropods that include lobsters, crabs, shrimp, insects, and spiders. Carbohydrates are classified as monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides depending on the number of monomers in the molecule. Monosaccharides are linked by glycosidic bonds that are formed as a result of dehydration reactions, forming disaccharides and polysaccharides with the elimination of a water molecule for each bond formed. Glucose, galactose, and fructose are common monosaccharides, whereas common disaccharides include lactose, maltose, and sucrose. Starch and glycogen, examples of polysaccharides, are the storage forms of glucose in plants and animals, respectively. The long polysaccharide chains may be branched or unbranched. Cellulose is an example of an unbranched polysaccharide, whereas amylopectin, a constituent of starch, is a highly branched molecule. Storage of glucose, in the form of polymers like starch of glycogen, makes it slightly less accessible for metabolism; however, this prevents it from leaking out of the cell or creating a high osmotic pressure that could cause excessive water uptake by the cell.

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

Candela Citations

- Introduction to Carbohydrates. Authored by: Shelli Carter and Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Biology. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8

- Bee On Flowers. Authored by: Larisa Koshkina. Located at: http://www.publicdomainpictures.net/view-image.php?image=22204. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright