Identify the common characteristics of fungi

The word fungus comes from the Latin word for mushrooms. Indeed, the familiar mushroom is a reproductive structure used by many types of fungi. However, there are also many fungi species that don’t produce mushrooms at all. Being eukaryotes, a typical fungal cell contains a true nucleus and many membrane-bound organelles. The kingdom Fungi includes an enormous variety of living organisms collectively referred to as Eucomycota, or true Fungi. While scientists have identified about 100,000 species of fungi, this is only a fraction of the 1.5 million species of fungus likely present on Earth. Edible mushrooms, yeasts, black mold, and the producer of the antibiotic penicillin, Penicillium notatum, are all members of the kingdom Fungi, which belongs to the domain Eukarya.

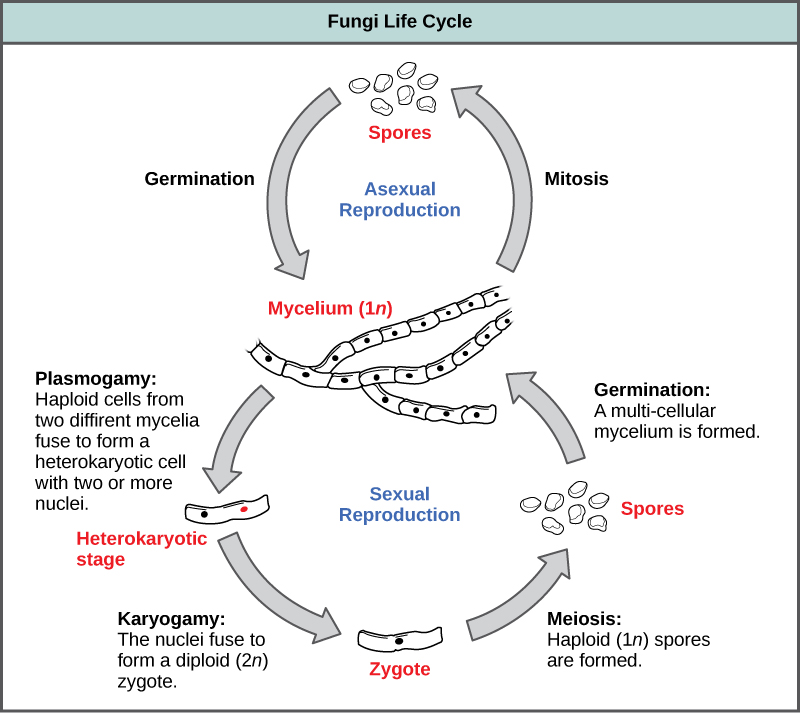

Fungi, once considered plant-like organisms, are more closely related to animals than plants. Fungi are not capable of photosynthesis: they are heterotrophic because they use complex organic compounds as sources of energy and carbon. Some fungal organisms multiply only asexually, whereas others undergo both asexual reproduction and sexual reproduction with alternation of generations. Most fungi produce a large number of spores, which are haploid cells that can undergo mitosis to form multicellular, haploid individuals. Like bacteria, fungi play an essential role in ecosystems because they are decomposers and participate in the cycling of nutrients by breaking down organic materials to simple molecules.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the common structures of fungi

- Identify common habitats of fungi

- Describe the mode of nutrition and growth in fungi

- Explain sexual and asexual reproduction in fungi

Cell Structure and Function

Fungi are eukaryotes, and as such, have a complex cellular organization. As eukaryotes, fungal cells contain a membrane-bound nucleus. The DNA in the nucleus is wrapped around histone proteins, as is observed in other eukaryotic cells. A few types of fungi have structures comparable to bacterial plasmids (loops of DNA); however, the horizontal transfer of genetic information from one mature bacterium to another rarely occurs in fungi. Fungal cells also contain mitochondria and a complex system of internal membranes, including the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus.

Figure 1. The poisonous Amanita muscaria is native to temperate and boreal regions of North America. (credit: Christine Majul)

Unlike plant cells, fungal cells do not have chloroplasts or chlorophyll. Many fungi display bright colors arising from other cellular pigments, ranging from red to green to black. The poisonous Amanita muscaria (fly agaric) is recognizable by its bright red cap with white patches (Figure 1). Pigments in fungi are associated with the cell wall and play a protective role against ultraviolet radiation. Some fungal pigments are toxic.

Like plant cells, fungal cells have a thick cell wall. The rigid layers of fungal cell walls contain complex polysaccharides called chitin and glucans. Chitin, also found in the exoskeleton of insects, gives structural strength to the cell walls of fungi. The wall protects the cell from desiccation and predators. Fungi have plasma membranes similar to other eukaryotes, except that the structure is stabilized by ergosterol: a steroid molecule that replaces the cholesterol found in animal cell membranes. Most members of the kingdom Fungi are nonmotile. Flagella are produced only by the gametes in the primitive Phylum Chytridiomycota.

Habitats

Although fungi are primarily associated with humid and cool environments that provide a supply of organic matter, they colonize a surprising diversity of habitats, from seawater to human skin and mucous membranes. Chytrids are found primarily in aquatic environments. Other fungi, such as Coccidioides immitis, which causes pneumonia when its spores are inhaled, thrive in the dry and sandy soil of the southwestern United States. Fungi that parasitize coral reefs live in the ocean. However, most members of the Kingdom Fungi grow on the forest floor, where the dark and damp environment is rich in decaying debris from plants and animals. In these environments, fungi play a major role as decomposers and recyclers, making it possible for members of the other kingdoms to be supplied with nutrients and live.

Nutrition

Like animals, fungi are heterotrophs; they use complex organic compounds as a source of carbon, rather than fix carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as do some bacteria and most plants. In addition, fungi do not fix nitrogen from the atmosphere. Like animals, they must obtain it from their diet. However, unlike most animals, which ingest food and then digest it internally in specialized organs, fungi perform these steps in the reverse order; digestion precedes ingestion. First, exoenzymes are transported out of the hyphae, where they process nutrients in the environment. Then, the smaller molecules produced by this external digestion are absorbed through the large surface area of the mycelium. As with animal cells, the polysaccharide of storage is glycogen, rather than starch, as found in plants.

Fungi are mostly saprobes (also known as saprophytes): organisms that derive nutrients from decaying organic matter. They obtain their nutrients from dead or decomposing organic matter: mainly plant material. Fungal exoenzymes are able to break down insoluble polysaccharides, such as the cellulose and lignin of dead wood, into readily absorbable glucose molecules. The carbon, nitrogen, and other elements are thus released into the environment. Because of their varied metabolic pathways, fungi fulfill an important ecological role and are being investigated as potential tools in bioremediation. For example, some species of fungi can be used to break down diesel oil and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Other species take up heavy metals, such as cadmium and lead.

Some fungi are parasitic, infecting either plants or animals. Smut and Dutch elm disease affect plants, whereas athlete’s foot and candidiasis (thrush) are medically important fungal infections in humans. In environments poor in nitrogen, some fungi resort to predation of nematodes (small non-segmented roundworms). Species of Arthrobotrys fungi have a number of mechanisms to trap nematodes. One mechanism involves constricting rings within the network of hyphae. The rings swell when they touch the nematode, gripping it in a tight hold. The fungus penetrates the tissue of the worm by extending specialized hyphae called haustoria. Many parasitic fungi possess haustoria, as these structures penetrate the tissues of the host, release digestive enzymes within the host’s body, and absorb the digested nutrients.

Growth

Figure 2. Candida albicans. (credit: modification of work by Dr. Godon Roberstad, CDC; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

The vegetative body of a fungus is a unicellular or multicellular thallus. Dimorphic fungi can change from the unicellular to multicellular state depending on environmental conditions. Unicellular fungi are generally referred to as yeasts. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast) and Candida species (the agents of thrush, a common fungal infection) are examples of unicellular fungi (Figure 2). Canadida albicans is a yeast cell and the agent of candidiasis and thrush and has a similar morphology to coccus bacteria; however, yeast is a eukaryotic organism (note the nucleus).

Most fungi are multicellular organisms. They display two distinct morphological stages: the vegetative and reproductive. The vegetative stage consists of a tangle of slender thread-like structures called hyphae (singular, hypha), whereas the reproductive stage can be more conspicuous. The mass of hyphae is a mycelium (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The mycelium of the fungus Neotestudina rosati can be pathogenic to humans. The fungus enters through a cut or scrape and develops a mycetoma, a chronic subcutaneous infection. (credit: CDC)

It can grow on a surface, in soil or decaying material, in a liquid, or even on living tissue. Although individual hyphae must be observed under a microscope, the mycelium of a fungus can be very large, with some species truly being “the fungus humongous.” The giant Armillaria solidipes (honey mushroom) is considered the largest organism on Earth, spreading across more than 2,000 acres of underground soil in eastern Oregon; it is estimated to be at least 2,400 years old.

Most fungal hyphae are divided into separate cells by endwalls called septa (singular, septum) (Figure 4a, c). In most phyla of fungi, tiny holes in the septa allow for the rapid flow of nutrients and small molecules from cell to cell along the hypha. They are described as perforated septa. The hyphae in bread molds (which belong to the Phylum Zygomycota) are not separated by septa. Instead, they are formed by large cells containing many nuclei, an arrangement described as coenocytic hyphae (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. Fungal hyphae may be (a) septated or (b) coenocytic (coeno- = “common”; -cytic = “cell”) with many nuclei present in a single hypha. A bright field light micrograph of (c) Phialophora richardsiae shows septa that divide the hyphae. (credit c: modification of work by Dr. Lucille Georg, CDC; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Fungi thrive in environments that are moist and slightly acidic, and can grow with or without light. They vary in their oxygen requirement. Most fungi are obligate aerobes, requiring oxygen to survive. Other species, such as the Chytridiomycota that reside in the rumen of cattle, are are obligate anaerobes, in that they only use anaerobic respiration because oxygen will disrupt their metabolism or kill them. Yeasts are intermediate, being facultative anaerobes. This means that they grow best in the presence of oxygen using aerobic respiration, but can survive using anaerobic respiration when oxygen is not available. The alcohol produced from yeast fermentation is used in wine and beer production.

Reproduction

Fungi reproduce sexually and/or asexually. Perfect fungi reproduce both sexually and asexually, while imperfect fungi reproduce only asexually (by mitosis).

In both sexual and asexual reproduction, fungi produce spores that disperse from the parent organism by either floating on the wind or hitching a ride on an animal. Fungal spores are smaller and lighter than plant seeds. The giant puffball mushroom bursts open and releases trillions of spores. The huge number of spores released increases the likelihood of landing in an environment that will support growth (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The (a) giant puff ball mushroom releases (b) a cloud of spores when it reaches maturity. (credit a: modification of work by Roger Griffith; credit b: modification of work by Pearson Scott Foresman, donated to the Wikimedia Foundation)

Asexual Reproduction

Figure 6. The dark cells in this bright field light micrograph are the pathogenic yeast Histoplasma capsulatum, seen against a backdrop of light blue tissue. (credit: modification of work by Dr. Libero Ajello, CDC; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Fungi reproduce asexually by fragmentation, budding, or producing spores. Fragments of hyphae can grow new colonies. Somatic cells in yeast form buds. During budding (a type of cytokinesis), a bulge forms on the side of the cell, the nucleus divides mitotically, and the bud ultimately detaches itself from the mother cell. Histoplasma (Figure 6) primarily infects lungs but can spread to other tissues, causing histoplasmosis, a potentially fatal disease.

The most common mode of asexual reproduction is through the formation of asexual spores, which are produced by one parent only (through mitosis) and are genetically identical to that parent (Figure 7). Spores allow fungi to expand their distribution and colonize new environments. They may be released from the parent thallus either outside or within a special reproductive sac called a sporangium.

Figure 7. Fungi may have both asexual and sexual stages of reproduction.

Figure 8. This bright field light micrograph shows the release of spores from a sporangium at the end of a hypha called a sporangiophore. The organism is a Mucor sp. fungus, a mold often found indoors. (credit: modification of work by Dr. Lucille Georg, CDC; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

There are many types of asexual spores. Conidiospores are unicellular or multicellular spores that are released directly from the tip or side of the hypha. Other asexual spores originate in the fragmentation of a hypha to form single cells that are released as spores; some of these have a thick wall surrounding the fragment. Yet others bud off the vegetative parent cell. Sporangiospores are produced in a sporangium (Figure 8).

Sexual Reproduction

Sexual reproduction introduces genetic variation into a population of fungi. In fungi, sexual reproduction often occurs in response to adverse environmental conditions. During sexual reproduction, two mating types are produced. When both mating types are present in the same mycelium, it is called homothallic, or self-fertile. Heterothallic mycelia require two different, but compatible, mycelia to reproduce sexually.

Although there are many variations in fungal sexual reproduction, all include the following three stages (Figure 7). First, during plasmogamy (literally, “marriage or union of cytoplasm”), two haploid cells fuse, leading to a dikaryotic stage where two haploid nuclei coexist in a single cell. During karyogamy (“nuclear marriage”), the haploid nuclei fuse to form a diploid zygote nucleus. Finally, meiosis takes place in the gametangia (singular, gametangium) organs, in which gametes of different mating types are generated. At this stage, spores are disseminated into the environment.

Fungivores

Animal dispersal is important for some fungi because an animal may carry spores considerable distances from the source. Fungal spores are rarely completely degraded in the gastrointestinal tract of an animal, and many are able to germinate when they are passed in the feces. Some dung fungi actually require passage through the digestive system of herbivores to complete their lifecycle. The black truffle—a prized gourmet delicacy—is the fruiting body of an underground mushroom. Almost all truffles are ectomycorrhizal, and are usually found in close association with trees. Animals eat truffles and disperse the spores. In Italy and France, truffle hunters use female pigs to sniff out truffles. Female pigs are attracted to truffles because the fungus releases a volatile compound closely related to a pheromone produced by male pigs.

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.