Describe the structure of prokaryotic cells

There are many differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. However, all cells have four common structures: the plasma membrane, which functions as a barrier for the cell and separates the cell from its environment; the cytoplasm, a jelly-like substance inside the cell; nucleic acids, the genetic material of the cell; and ribosomes, where protein synthesis takes place. Prokaryotes come in various shapes, but many fall into three categories: cocci (spherical), bacilli (rod-shaped), and spirilli (spiral-shaped) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prokaryotes fall into three basic categories based on their shape, visualized here using scanning electron microscopy: (a) cocci, or spherical (a pair is shown); (b) bacilli, or rod-shaped; and (c) spirilli, or spiral-shaped. (credit a: modification of work by Janice Haney Carr, Dr. Richard Facklam, CDC; credit c: modification of work by Dr. David Cox; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Learning Objectives

- Describe the basic structure of a typical prokaryote

- Describe important differences in structure between Archaea and Bacteria

The Prokaryotic Cell

All cells share four common components: (1) a plasma membrane, an outer covering that separates the cell’s interior from its surrounding environment; (2) cytoplasm, consisting of a jelly-like region within the cell in which other cellular components are found; (3) DNA, the genetic material of the cell; and (4) ribosomes, particles that synthesize proteins. Prokaryotic cells differ from eukaryotic cells in several key ways.

Figure 2. The features of a typical prokaryotic cell are shown.

A prokaryotic cell is a simple, single-celled (unicellular) organism that lacks a nucleus, or any other membrane-bound organelle. Prokaryotic DNA is found in the central part of the cell: a darkened region called the nucleoid (Figure 2).

Some prokaryotes have flagella, pili, or fimbriae. Flagella are used for locomotion, while most pili are used to exchange genetic material during a type of reproduction called conjugation. Many prokaryotes also have a cell wall and capsule. The cell wall acts as an extra layer of protection, helps the cell maintain its shape, and prevents dehydration. The capsule enables the cell to attach to surfaces in its environment.

Reproduction

Reproduction in prokaryotes is asexual and usually takes place by binary fission. Recall that the DNA of a prokaryote exists as a single, circular chromosome. Prokaryotes do not undergo mitosis. Rather the chromosome is replicated and the two resulting copies separate from one another due to the growth of the cell. The prokaryote, now enlarged, is pinched inward at its equator and the two resulting cells, which are clones, separate. Binary fission does not provide an opportunity for genetic recombination or genetic diversity, but prokaryotes can share genes by three other mechanisms.

In transformation, the prokaryote takes in DNA found in its environment that is shed by other prokaryotes. If a nonpathogenic bacterium takes up DNA for a toxin gene from a pathogen and incorporates the new DNA into its own chromosome, it too may become pathogenic. In transduction, bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria, sometimes also move short pieces of chromosomal DNA from one bacterium to another. Transduction results in a recombinant organism. Archaea are not affected by bacteriophages but instead have their own viruses that translocate genetic material from one individual to another. In conjugation, DNA is transferred from one prokaryote to another by means of a pilus, which brings the organisms into contact with one another. The DNA transferred can be in the form of a plasmid, a small circular piece of extrachromosomal DNA, or as a hybrid, containing both plasmid and chromosomal DNA. These three processes of DNA exchange are shown in Figure 3.

Reproduction can be very rapid: a few minutes for some species. This short generation time coupled with mechanisms of genetic recombination and high rates of mutation result in the rapid evolution of prokaryotes, allowing them to respond to environmental changes (such as the introduction of an antibiotic) very quickly.

Figure 3. Besides binary fission, there are three other mechanisms by which prokaryotes can exchange DNA. In (a) transformation, the cell takes up prokaryotic DNA directly from the environment. The DNA may remain separate as plasmid DNA or be incorporated into the host genome. In (b) transduction, a bacteriophage injects DNA into the cell that contains a small fragment of DNA from a different prokaryote. In (c) conjugation, DNA is transferred from one cell to another via a mating bridge that connects the two cells after the sex pilus draws the two bacteria close enough to form the bridge.

The Evolution of Prokaryotes

How do scientists answer questions about the evolution of prokaryotes? Unlike with animals, artifacts in the fossil record of prokaryotes offer very little information. Fossils of ancient prokaryotes look like tiny bubbles in rock. Some scientists turn to genetics and to the principle of the molecular clock, which holds that the more recently two species have diverged, the more similar their genes (and thus proteins) will be. Conversely, species that diverged long ago will have more genes that are dissimilar.

Scientists at the NASA Astrobiology Institute and at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory collaborated to analyze the molecular evolution of 32 specific proteins common to 72 species of prokaryotes.[1] The model they derived from their data indicates that three important groups of bacteria—Actinobacteria, Deinococcus, and Cyanobacteria (which the authors call Terrabacteria)—were the first to colonize land. (Recall that Deinococcus is a genus of prokaryote—a bacterium—that is highly resistant to ionizing radiation.) Cyanobacteria are photosynthesizers, while Actinobacteria are a group of very common bacteria that include species important in decomposition of organic wastes.

The timelines of divergence suggest that bacteria (members of the domain Bacteria) diverged from common ancestral species between 2.5 and 3.2 billion years ago, whereas archaea diverged earlier: between 3.1 and 4.1 billion years ago. Eukarya later diverged off the Archaean line. The work further suggests that stromatolites that formed prior to the advent of cyanobacteria (about 2.6 billion years ago) photosynthesized in an anoxic environment and that because of the modifications of the Terrabacteria for land (resistance to drying and the possession of compounds that protect the organism from excess light), photosynthesis using oxygen may be closely linked to adaptations to survive on land.

Archaea vs. Bacteria

Prokaryotes are divided into two different domains, Bacteria and Archaea, which together with Eukarya, comprise the three domains of life (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Bacteria and Archaea are both prokaryotes but differ enough to be placed in separate domains. An ancestor of modern Archaea is believed to have given rise to Eukarya, the third domain of life. Archaeal and bacterial phyla are shown; the evolutionary relationship between these phyla is still open to debate.

The composition of the cell wall differs significantly between the domains Bacteria and Archaea. The composition of their cell walls also differs from the eukaryotic cell walls found in plants (cellulose) or fungi and insects (chitin). The cell wall functions as a protective layer, and it is responsible for the organism’s shape. Some bacteria have an outer capsule outside the cell wall. Other structures are present in some prokaryotic species, but not in others. For example, the capsule found in some species enables the organism to attach to surfaces, protects it from dehydration and attack by phagocytic cells, and makes pathogens more resistant to our immune responses. Some species also have flagella (singular, flagellum) used for locomotion, and pili (singular, pilus) used for attachment to surfaces. Plasmids, which consist of extra-chromosomal DNA, are also present in many species of bacteria and archaea.

Phylum Proteobacteria is one of up to 52 bacteria phyla. Proteobacteria is further subdivided into five classes, Alpha through Epsilon (Table 1).

| Table 1. Bacteria of Phylum Proteobacteria | ||

|---|---|---|

| Class | Representative organisms | Representative micrograph |

| Alpha proteobacteria

Some species are photoautotrophic, but some are symbionts of plants and animals, and others are pathogens. Eukaryotic mitochondria are thought to be derived from bacteria in this group. |

Rhizobium: Nitrogen-fixing endosymbiont associated with roots of legumes

Rickettsia: Obligate intracellular parasite that causes typhus and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever |

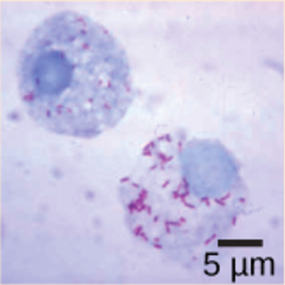

Rickettsia rickettsia, staid red, growing inside a host cell |

| Beta proteobacteria

This group of bacteria is divers. Some species play an important role in the nitrogen cycle. |

Nitrosomas: Species from this group oxidize ammonia into nitrite

Spirillum minus: Causes rat-bite fever |

Spirillum minus |

| Gamma proteobacteria

Many are beneficial symbionts that populate the human gut, but others are familiar human pathogens. Some species from this subgroup oxidize sulfur compounds. |

E. coli: Normally beneficial microbe of the human gut, but some strains cause disease

Salmonella: Certain strains cause food poisoning or typhoid fever V. cholera: Causative agent of cholera Chromatium: Sulfur-producing bacteria that oxidize sulfur, producing H2S |

Vibrio cholera |

| Delta proteobacteria

Some species generate a spore-forming fruiting body in adverse conditions. Others reduce sulfate and sulfur. |

Myxobacteria: Generate spore-forming fruiting bodies in adverse conditions

Desulfovibrio vulgaris: Anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacterium |

Desulfovibrio vulgaris |

| Epsilon proteobacteria

Many species inhabit the digestive tract of animals as symbionts or pathogens. Bacteria from this group have been found in deep-sea hydrothermal vents and cold seep habitats. |

Campylobacter: Causes blood poisoning and intestinal inflammation

H. pylori: Causes stomach ulcers |

Campylobacter |

| (credit “Rickettsia rickettsia”: modification of work by CDC; credit “Spirillum minus”: modification of work by Wolframm Adlassnig; credit “Vibrio cholera”: modification of work by Janice Haney Carr, CDC; credit “Desulfovibrio vulgaris”: modification of work by Graham Bradley; credit “Campylobacter”: modification of work by De Wood, Pooley, USDA, ARS, EMU; scale-bar data from Matt Russell) | ||

Chlamydia, Spirochetes, Cyanobacteria, and Gram-positive bacteria are described in Table 2. Note that bacterial shape is not phylum-dependent; bacteria within a phylum may be cocci, rod-shaped, or spiral.

| Table 2. Bacteria: Chlamydia, Spirochetes, Cyanobacteria, and Gram-positive | ||

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Representative organisms | Representative micrograph |

| Chlamydias

All members of this group are obligate intracellular parasites of animal cells. Cell walls lack peptidoglycan |

Chlamydia trachomatis: Common sexually transmitted disease that can lead to blindness |

In this pap smear, Chlamydia trachomatis appear as pink inclusions inside cells |

| Spirochetes

Most members of this phylum, which has spiral-shaped cells, are free-living anaerobes, but some are pathogenic. Flagella run lengthwise in the periplasmic space between the inner and outer membrane |

Treponema pallidum: Causative agent of syphillis

Borrelia burgdorferi: Causative agent of Lyme disease |

Treponema pallidum |

| Cyanobacteria

Also known as blue-green algae, these bacteria obtain their energy through photosynthesis. They are ubiquitous, found in terrestrial, marine, and freshwater environments. Eukaryotic chloroplasts are thought to be derived from bacteria in this class. |

Prochlorococcus: Believed to be the most abundant photosynthetic organism on earth, it is responsible for generating half the world’s oxygen |

Phormidium |

| Gram-positive Bacteria

Soil-dwelling members of this subgroup decompose organic matter. Some species cause disease. They have a thick cell wall and lack an outer membrane. |

Clostridium botulinum: Causes Botullism

Steptomyces: Many antibiotics, including streptomyocin, are derived from these bacteria Mycoplasmas: These tiny bacteria, the smallest known, lack a cell wall. Some are free-living, and some are pathogenic |

Clostridium difficile |

| (credit “Chlamydia trachomatis”: modification of work by Dr. Lance Liotta Laboratory, NCI; credit “Treponema pallidum”: modification of work by Dr. David Cox, CDC; credit “Phormidium”: modification of work by USGS; credit “Clostridium difficile”: modification of work by Lois S. Wiggs, CDC; scale-bar data from Matt Russell) | ||

Archaea are separated into four phyla: the Euryarchaeota, Crenarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota, and Korarchaeota.

| Table 3. Archaea | ||

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Representative organisms | Representative micrograph |

| Euryarchaeota

This phylum includes methanogens, which produce methane as a metabolic waste product, and halobacteria, which live in an extreme saline environment. |

Methanogens: Methane production causes flatulence in humans and other animals.

Halobacteria: Large blooms of this salt-loving archaea appear reddish due to the presence of bacteriorhodopsin in the membrane. Bacteriorhodopsin is related to the retinal pigment rhodopsin. |

Halobacterium strain NRC-1 |

| Crenarchaeota

Members of this ubiquitous phylum play an important role in the fixation of carbon. Many members of this group are sulfur-dependent extremophiles. Some are thermophilic or hyperthermophilic. |

Sulfolobus: Members of this genus grow in volcanic springs at temperatures between 75º and 80º C and at a pH between 2 and 3. |

Sulfolobus being infected by bacteriophage |

| Nanoarchaeota

This group currently contains only one species: Nanoarchaeum equitans. |

Nanoarchaeum equitans: This species was isolated from the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean and from a hydrothermal vent at Yellowstone National Park. It is an obligate symbiont with Ignicoccus, another species of archaea. |

Nanoarchaeum equitans (small dark spheres) are in contact with their larger host, Ignococcus |

| Korarchaeota

This group is considered to be one of the most primitive forms of life. Members of this phylum have only been found in the Obsidian Pool, a hot spring at Yellowstone National Park. |

No members of this species have been cultivated. |

This image shows a variety of korarchaeota species from the Obsidian Pool at Yellowstone National Park. |

| (credit “Halobacterium”: modification of work by NASA; credit “Nanoarchaeotum equitans”: modification of work by Karl O. Stetter; credit “korarchaeota”: modification of work by Office of Science of the U.S. Dept. of Energy; scale-bar data from Matt Russell) | ||

The Plasma Membrane

The plasma membrane is a thin lipid bilayer (6 to 8 nanometers) that completely surrounds the cell and separates the inside from the outside. Its selectively permeable nature keeps ions, proteins, and other molecules within the cell and prevents them from diffusing into the extracellular environment, while other molecules may move through the membrane. Recall that the general structure of a cell membrane is a phospholipid bilayer composed of two layers of lipid molecules. In archaeal cell membranes, isoprene (phytanyl) chains linked to glycerol replace the fatty acids linked to glycerol in bacterial membranes. Some archaeal membranes are lipid monolayers instead of bilayers (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Archaeal phospholipids differ from those found in Bacteria and Eukarya in two ways. First, they have branched phytanyl sidechains instead of linear ones. Second, an ether bond instead of an ester bond connects the lipid to the glycerol.

The Cell Wall

The cytoplasm of prokaryotic cells has a high concentration of dissolved solutes. Therefore, the osmotic pressure within the cell is relatively high. The cell wall is a protective layer that surrounds some cells and gives them shape and rigidity. It is located outside the cell membrane and prevents osmotic lysis (bursting due to increasing volume). The chemical composition of the cell walls varies between archaea and bacteria, and also varies between bacterial species.

Bacterial cell walls contain peptidoglycan, composed of polysaccharide chains that are cross-linked by unusual peptides containing both L- and D-amino acids including D-glutamic acid and D-alanine. Proteins normally have only L-amino acids; as a consequence, many of our antibiotics work by mimicking D-amino acids and therefore have specific effects on bacterial cell wall development. There are more than 100 different forms of peptidoglycan. S-layer (surface layer) proteins are also present on the outside of cell walls of both archaea and bacteria.

Bacteria are divided into two major groups: Gram positive and Gram negative, based on their reaction to Gram staining. Note that all Gram-positive bacteria belong to one phylum; bacteria in the other phyla (Proteobacteria, Chlamydias, Spirochetes, Cyanobacteria, and others) are Gram-negative. The Gram staining method is named after its inventor, Danish scientist Hans Christian Gram (1853–1938). The different bacterial responses to the staining procedure are ultimately due to cell wall structure. Gram-positive organisms typically lack the outer membrane found in Gram-negative organisms (Figure 6). Up to 90 percent of the cell wall in Gram-positive bacteria is composed of peptidoglycan, and most of the rest is composed of acidic substances called teichoic acids. Teichoic acids may be covalently linked to lipids in the plasma membrane to form lipoteichoic acids. Lipoteichoic acids anchor the cell wall to the cell membrane. Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall composed of a few layers of peptidoglycan (only 10 percent of the total cell wall), surrounded by an outer envelope containing lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and lipoproteins. This outer envelope is sometimes referred to as a second lipid bilayer. The chemistry of this outer envelope is very different, however, from that of the typical lipid bilayer that forms plasma membranes.

Practice Question

Bacteria are divided into two major groups: Gram positive and Gram negative. Both groups have a cell wall composed of peptidoglycan: in Gram-positive bacteria, the wall is thick, whereas in Gram-negative bacteria, the wall is thin. In Gram-negative bacteria, the cell wall is surrounded by an outer membrane that contains lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins. Porins are proteins in this cell membrane that allow substances to pass through the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. In Gram-positive bacteria, lipoteichoic acid anchors the cell wall to the cell membrane.

Figure 6. Gram-positive and -negative bacteria (credit: modification of work by “Franciscosp2″/Wikimedia Commons)

Which of the following statements is true?

- Gram-positive bacteria have a single cell wall anchored to the cell membrane by lipoteichoic acid.

- Porins allow entry of substances into both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

- The cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria is thick, and the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria is thin.

- Gram-negative bacteria have a cell wall made of peptidoglycan, whereas Gram-positive bacteria have a cell wall made of lipoteichoic acid.

Archaean cell walls do not have peptidoglycan. There are four different types of Archaean cell walls. One type is composed of pseudopeptidoglycan, which is similar to peptidoglycan in morphology but contains different sugars in the polysaccharide chain. The other three types of cell walls are composed of polysaccharides, glycoproteins, or pure protein.

In Summary: The Structure of Prokaryotes

Prokaryotes (domains Archaea and Bacteria) are single-celled organisms lacking a nucleus. They have a single piece of circular DNA in the nucleoid area of the cell. Most prokaryotes have a cell wall that lies outside the boundary of the plasma membrane. Some prokaryotes may have additional structures such as a capsule, flagella, and pili.

| Table 4. Structural Differences and Similarities between Bacteria and Archaea | ||

|---|---|---|

| Structural Characteristic | Bacteria | Archaea |

| Cell type | Prokaryotic | Prokaryotic |

| Cell morphology | Variable | Variable |

| Cell wall | Contains peptidoglycan | Does not contain peptidoglycan |

| Cell membrane type | Lipid bilayer | Lipid bilayer or lipid monolayer |

| Plasma membrane lipids | Fatty acids | Phytanyl groups |

Bacteria and Archaea differ in the lipid composition of their cell membranes and the characteristics of the cell wall. In archaeal membranes, phytanyl units, rather than fatty acids, are linked to glycerol. Some archaeal membranes are lipid monolayers instead of bilayers.

The cell wall is located outside the cell membrane and prevents osmotic lysis. The chemical composition of cell walls varies between species. Bacterial cell walls contain peptidoglycan. Archaean cell walls do not have peptidoglycan, but they may have pseudopeptidoglycan, polysaccharides, glycoproteins, or protein-based cell walls. Bacteria can be divided into two major groups: Gram positive and Gram negative, based on the Gram stain reaction. Gram-positive organisms have a thick cell wall, together with teichoic acids. Gram-negative organisms have a thin cell wall and an outer envelope containing lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins.

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

Candela Citations

- Introduction to the Structure of Prokaryotes. Authored by: Shelli Carter and Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Biology. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8

- Battistuzzi, FU, Feijao, A, and Hedges, SB. A genomic timescale of prokaryote evolution: Insights into the origin of methanogenesis, phototrophy, and the colonization of land. BioMed Central: Evolutionary Biology 4 (2004): 44, doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-44. ↵