26.1.3: Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia, a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America, was created in 1819 by Simón Bolívar as part of his vision for a unified Latin America, but was fraught with political instability and collapsed in 1831.

Learning Objective

Identify Gran Colombia and the modern states it later became

Key Points

- As the wars of independence in Latin America were being fought, Simón Bolívar developed a vision for a unified Latin America to protect the new independence from European interests.

- Out of this vision, Gran Colombia was formed in 1819 following Bolívar’s victory against the Spanish at the Battle of Carabobo; he was elected the president.

- In its first years, Gran Colombia helped other provinces still at war with Spain become independent, adding more territories to its federation; by 1824 it had 12 administrative departments.

- The history of Gran Colombia was marked by a struggle between those who supported a centralized government with a strong presidency and those who supported a decentralized, federal form of government.

- After years of struggle between the centralists and federalists, in 1828 delegates met to create a new constitution which Bolívar proposed to base on Bolivia’s, but it was unpopular and the constitutional convention fell apart.

- In two years, Bolívar resigned as president and within a year, Gran Colombia dissolved, forming the independent states of Venezuela, Ecuador, and New Granada.

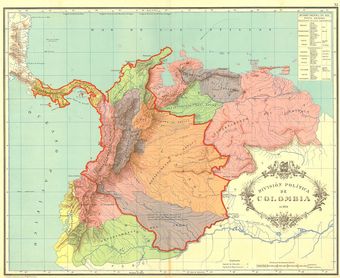

- Gran Colombia included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil.

Key Terms

- Battle of Carabobo

- A battle fought between independence fighters led by Venezuelan General Simón Bolívar and the Royalist forces led by Spanish Field Marshal Miguel de la Torre. Bolívar’s decisive victory at Carabobo led to the independence of Venezuela and establishment of the Republic of Gran Colombia.

- federation

- A political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing states or regions under a central government. Typically, the self-governing status of the component states, as well as the division of power between them and the central government, is constitutionally entrenched and may not be altered by a unilateral decision of either party.

- New Granada

- The name given on May 27, 1717, to the jurisdiction of the Spanish Empire in northern South America, corresponding to modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela.

Gran Colombia is a name used today for the state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 1831. It included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil.

The first three were the successor states to Gran Colombia at its dissolution. Panama was separated from Colombia in 1903. Since Gran Colombia’s territory corresponded more or less to the original jurisdiction of the former Viceroyalty of New Granada, it also claimed the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, the Mosquito Coast.

Its existence was marked by a struggle between those who supported a centralized government with a strong presidency and those who supported a decentralized, federal form of government.

At the same time, another political division emerged between those who supported the Constitution of Cúcuta and two groups who sought to do away with the Constitution, either in favor of breaking up the nation into smaller republics or maintaining the union but creating an even stronger presidency. The faction that favored constitutional rule coalesced around Vice-President Francisco de Paula Santander, while those who supported the creation of a stronger presidency were led by President Simón Bolívar. The two men had been allies in the war against Spanish rule, but by 1825, their differences became public and contributed to the political instability from that year onward. Gran Columbia broke apart in 1831.

History of Gran Colombia

As Bolívar made advances against the royalist forces during the Venezuelan war of independence, he began to propose the creation of various large states and confederations, inspired by Francisco de Miranda’s idea of an independent state consisting of all of Spanish America, called “Colombia,” the “American Empire,” or the “American Federation.” The aim was to ensure the independence of Spanish America and protect the area’s newly won autonomy. In 1819 Bolívar was able to successfully create a nation called “Colombia” (today referred to as Gran Colombia) out of several Spanish American provinces.

Since the new nation was quickly proclaimed after Bolívar’s unexpected victory in New Granada, its government was temporarily set up as a federal republic, made up of three departments headed by a vice-president and with capitals in the cities of cities of Bogotá (Cundinamarca Department), Caracas (Venezuela Department), and Quito (Quito Department).

The Constitution of Cúcuta was drafted in 1821 at the Congress of Cúcuta, establishing the republic’s capital in Bogotá. Bolívar and Santander were elected as the nation’s president and vice-president. A great degree of centralization was established by the assembly at Cúcuta, since several New Granadan and Venezuelan deputies of the Congress who were formerly ardent federalists now came to believe that centralism was necessary to successfully manage the war against the royalists. The departments created in 1819 were split into 12 smaller departments, each governed by an intendant appointed by the central government. Since not all of the provinces were represented at Cúcuta because many areas of the nation remained in royalist hands, the congress called for a new constitutional convention to meet in ten years.

In its first years, Gran Colombia helped other provinces still at war with Spain to become independent: all of Venezuela except Puerto Cabello was liberated at the Battle of Carabobo, Panama joined the federation in November 1821, and the provinces of Pasto, Guayaquil, and Quito in 1822. The Gran Colombian army later consolidated the independence of Peru in 1824. Bolívar and Santander were re-elected in 1826.

As the war against Spain came to an end in the mid-1820s, federalist and regionalist sentiments that were suppressed for the sake of the war arose once again. There were calls for a modification of the political division, and related economic and commercial disputes between regions reappeared. Ecuador had important economic and political grievances. Since the end of the 18th century, its textile industry suffered because cheaper textiles were being imported. After independence, Gran Colombia adopted a low-tariff policy, which benefited agricultural regions such as Venezuela. Moreover, from 1820 to 1825, the area was ruled directly by Bolívar because of the extraordinary powers granted to him. His top priority was the war in Peru against the royalists, not solving Ecuador’s economic problems.

The strongest calls for a federal arrangement came from Venezuela, where there was strong federalist sentiment among the region’s liberals, many of whom had not fought in the war of independence but supported Spanish liberalism in the previous decade and now allied themselves with the conservative Commandant General of the Department of Venezuela, José Antonio Páez, against the central government.

In 1826, Venezuela came close to seceding from Gran Colombia. That year, Congress began impeachment proceedings against Páez, who resigned his post on April 28 but reassumed it two days later in defiance of the central government.

In November, two assemblies met in Venezuela to discuss the future of the region, but no formal independence was declared at either. That same month, skirmishes broke out between the supporters of Páez and Bolívar in the east and south of Venezuela. By the end of the year, Bolívar was in Maracaibo preparing to march into Venezuela with an army, if necessary. Ultimately, political compromises prevented this. In January, Bolívar offered the rebellious Venezuelans a general amnesty and the promise to convene a new constitutional assembly before the ten-year period established by the Constitution of Cúcuta, and Páez backed down and recognized Bolívar’s authority. The reforms, however, never fully satisfied the different political factions in Gran Colombia, and no permanent consolidation was achieved. The instability of the state’s structure was now apparent to all.

In 1828, the new constitutional assembly, the Convention of Ocaña, began its sessions. At its opening, Bolívar again proposed a new constitution based on the Bolivian one, but this suggestion continued to be unpopular. The convention fell apart when pro-Bolívar delegates walked out rather than sign a federalist constitution. After this failure, Bolívar believed that by centralizing his constitutional powers he could prevent the separatists from bringing down the union. He ultimately failed to do so. As the collapse of the nation became evident in 1830, Bolívar resigned from the presidency. Internal political strife between the different regions intensified even as General Rafael Urdaneta temporarily took power in Bogotá, attempting to use his authority to ostensibly restore order but actually hoping to convince Bolívar to return to the presidency and the nation to accept him. The federation finally dissolved in the closing months of 1830 and was formally abolished in 1831. Venezuela, Ecuador, and New Granada came to exist as independent states.

Gran Colombia A map of Gran Colombia showing the 12 departments created in 1824 and territories disputed with neighboring countries.

Attributions

- Gran Colombia

-

“Latin American integration.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_American_integration. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Gran_Colombia_map_1824.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gran_Colombia_map_1824.jpg. Wikimedia Commons Public domain.

-

Candela Citations

- Boundless World History. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/. License: CC BY: Attribution