35.1.6: The Sino-Soviet Split

The Sino-Soviet split was the deterioration and eventual breakup of political and ideological relations between China and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, which had massive domestic and geopolitical consequences.

Learning Objective

Discuss why the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic broke their relations and the consequences of the split

Key Points

- Mao and his supporters argued that traditional Marxism was rooted in industrialized European society and could not be applied to Asian peasant societies. However, although Mao continued to develop his own thought based on that presumption, in the 1950s, Soviet-guided China followed Stalin’s model of centralized economic development.

- After Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev made an effort to further the burgeoning relations with China begun by Stalin, traveling to the country and making various deals with the Chinese leadership that expanded the economic and political alliances between the two countries. The 1953-56 period has been called the “golden age” of Sino-Soviet relations.

- Relations between the USSR and the PRC began to deteriorate in 1956 after Khrushchev revealed his “Secret Speech” at the 20th Communist Party Congress. The “Secret Speech” criticized many of Stalin’s policies, especially his purges of Party members, and marked the beginning of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization process. This created a serious domestic problem for Mao, who had supported many of Stalin’s policies and modeled many of his own after them.

- At first, the Sino-Soviet split manifested indirectly as criticism towards each other’s client states. By 1960, the mutual criticism became public when Khrushchev and Peng Zhen had an open argument at the Romanian Communist Party congress.After a series of unconvincing compromises and explicitly hostile gestures, in 1962, the PRC and the USSR finally broke relations.

- The split, seen by historians as one of the key events of the Cold War, had massive consequences for the two powers and for the world. The USSR had a network of communist parties it supported. China now created its own rival network to battle it out for local control of the left in numerous countries. Mao launched the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), largely to prevent the development of Russian-style bureaucratic communism of the USSR. The ideological split also escalated to small-scale warfare between Russia and China.

- After the regime of Mao Zedong, the PRC–USSR ideological schism no longer shaped domestic politics but continued to impact geopolitics, including such global developments as the establishment of post-colonial Indochina, the Cambodian-Vietnamese War (1975–79) that deposed Pol Pot in 1978, the Sino-Vietnamese War (1979), and the 1979 invasion of the USSR on Afghanistan. Relations between China and the Soviet Union remained tense until the visit of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to Beijing in 1989.

Key Terms

- Cultural Revolution

- A sociopolitical movement that took place in China from 1966 until 1976. Set into motion by Mao Zedong, then Chairman of the Communist Party of China, its stated goal was to preserve ‘true’ Communist ideology in the country by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society and reimposing Maoist thought as the dominant ideology within the Party. The movement paralyzed China politically and had significant negative effects on economy and society.

- Hundred Flowers Campaign

- A period in 1956 in the People’s Republic of China during which the Communist Party of China (CPC) encouraged its citizens to openly express their opinions of the communist regime. Differing views and solutions to national policy were encouraged based on the famous expression by Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong: “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” After this brief period of liberalization, Mao abruptly changed course.

- Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech”

- A report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on February 25, 1956. Khrushchev was sharply critical of the reign of deceased General Secretary and Premier Joseph Stalin, particularly with respect to the purges which marked the late 1930s.

- Five Year Plan

- A nationwide centralized economic plan in the Soviet Union developed by a state planning committee that was part of the ideology of the Communist Party for the development of the Soviet economy. A series of these plans was developed in the Soviet Union while similar Soviet-inspired plans emerged across other communist countries during the Cold War era.

- Great Leap Forward

- An economic and social campaign by the Communist Party of China (CPC) that took place from 1958 to 1961 and was led by Mao Zedong. It aimed to rapidly transform the country from an agrarian economy into a socialist society through rapid industrialization and collectivization. It is widely considered to have caused the Great Chinese Famine.

- Cuban missile crisis

- A 13-day (October 16–28, 1962) confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union concerning American ballistic missile deployment in Italy and Turkey with consequent Soviet ballistic missile deployment in Cuba. The confrontation, elements of which were televised, was the closest the Cold War came to escalating into a full-scale nuclear war.

Background: Mao and Joseph Stalin

During both the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) against the Japanese Empire and the ongoing Chinese Civil War against the Nationalist Kuomintang, Mao Zedong ignored much of the politico-military advice and direction from Soviet General Secretary Joseph Stalin and the Comintern because of the practical difficulty in applying traditional Leninist revolutionary theory to China. After World War II, Stalin advised Mao against seizing power because the Soviet Union had signed a Treaty of Friendship and Alliance with the Nationalists in 1945. This time, Mao obeyed Stalin’s advice, calling him “the only leader of our party.” However, Stalin broke the treaty, requiring Soviet withdrawal from Manchuria three months after Japan’s surrender, and gave Manchuria to Mao. After the CPC’s victory over the KMT, a Moscow visit by Mao from December 1949 to February 1950 culminated in the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance (1950), which included a $300 million low-interest loan and a 30-year military alliance clause.

However, Mao and his supporters argued that traditional Marxism was rooted in industrialized European society and could not be applied to Asian peasant societies. Although Mao continued to develop his own thought based on that presumption, in the 1950s, Soviet-guided China followed the Soviet model of centralized economic development, emphasizing heavy industry and not treating consumer goods as a priority. Simultaneously, by the late 1950s, Mao had developed ideas that became the basis for the Great Leap Forward (1958–61), a campaign based on the assumption of the centrality of the rural working class to China’s economy and political system.

Communism after Stalin’s Death

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev made an effort to further the burgeoning relations with China begun by Stalin, traveling to the country in 1954 and making deals with the Chinese leadership that expanded the economic and political alliances between the two countries. Khrushchev also acknowledged Stalin’s unfair trade deals and revealed a list of active KGB agents placed in China during Stalin’s reign. Khrushchev was able to reach many prominent economic agreements during his visit, including an additional loan for economic development from the USSR to the PRC and a trade of human capital that included sending Soviet economic experts and political advisors to China and Chinese economic experts and unskilled labor to the USSR.

In 1955, relations only continued to improve. Economic trade collaboration began to develop to the point that 60% of Chinese exports were to the USSR. Mao also began to implement the Chinese but USSR-modeled Five Year Plan. Mao also promoted and encouraged the collectivization of agriculture in the PRC, applauding Stalin’s policies towards agriculture and industrialization. Finally, the two countries collaborated when setting their respective foreign policies. This period, from roughly Stalin’s death in 1953 to Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” in 1956, has been called the “golden age” of Sino-Soviet relations.

Photograph of Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Nikita Khrushchev: publicly, international allies; privately, ideological enemies. (China,1958, author unknown).: Although before 1956 Mao and Khrushchev managed to sign numerous agreements between China and the Soviet Union, the two leaders did not develop a positive personal relationship. Mao found Khrushchev’s personality grating and Khrushchev was unimpressed by Chinese culture.

The Sino-Soviet Split

Relations between the USSR and the PRC began to deteriorate in 1956 after Khrushchev revealed his “Secret Speech” at the 20th Communist Party Congress. The “Secret Speech” criticized many of Stalin’s policies, especially his purges of Party members, and marked the beginning of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization process. This created a serious domestic problem for Mao, who had supported many of Stalin’s policies and modeled many of his own after them. With Khrushchev’s denouncement of Stalin, many people questioned Mao’s decisions. Moreover, the emergence of movements fighting for the reforms of the existing communist systems across East-Central Europe after Khrushchev’s speech worried Mao. Brief political liberalization introduced to prevent similar movements in China, most notably lessened political censorship known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign, backfired against Mao, whose position within the Party only weakened. This convinced him further that de-Stalinization was a mistake. Mao took a sharp turn to the left ideologically, which contrasted with the ideological softening of de-Stalinization. With Khrushchev’s strengthening position as Soviet leader, the two countries were set on two different ideological paths.

Mao’s implementation of the Great Leap Forward, which utilized communist policies closer to Stalin than to Khrushchev, including forming a personality cult around Mao as well as more Stalinist economic policies. This angered the USSR, especially after Mao criticized Khrushchev’s economic policies through the plan while also calling for more Soviet aid. The Soviet leader saw the new policies as evidence of an increasingly confrontational and unpredictable China.

At first, the Sino-Soviet split manifested indirectly as criticism towards each other’s client states. China denounced Yugoslavia and Tito, who pursued a non-aligned foreign policy, while the USSR denounced Enver Hoxha and the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania, which refused to abandon its pro-Stalin stance and sought its survival in alignment with China. The USSR also offered moral support to the Tibetan rebels in their 1959 Tibetan uprising against China. By 1960, the mutual criticism moved out in the open, when Khrushchev and Peng Zhen had an open argument at the Romanian Communist Party congress. Khrushchev characterized Mao as “a nationalist, an adventurist, and a deviationist.” In turn, China’s Peng Zhen called Khrushchev a Marxist revisionist, criticizing him as “patriarchal, arbitrary and tyrannical.” Khrushchev denounced China with an 80-page letter to the conference and responded to Mao by withdrawing around 1,400 Soviet experts and technicians from China, leading to the cancellation of more than 200 scientific projects intended to foster cooperation between the two nations.

After a series of unconvincing compromises and explicitly hostile gestures, in 1962, the PRC and the USSR finally broke relations. Mao criticized Khrushchev for withdrawing from the Cuban missile crisis (1962). Khrushchev replied angrily that Mao’s confrontational policies would lead to a nuclear war. In the wake of the Cuban missile crisis, nuclear disarmament was brought to the forefront of geopolitics. To curb the production of nuclear weapons in other nations, the Soviet Union, Britain, and the U.S. signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty in 1963. At the time, China was developing its own nuclear weaponry and Mao saw the treaty as an attempt to slow China’s advancement as a superpower. This was the final straw for Mao, who from September 1963 to July 1964 published nine letters openly criticizing every aspect of Khrushchev’s leadership.

The Sino-Soviet alliance now completely collapsed and Mao turned to other Asian, African, and Latin American countries to develop new and stronger alliances and further the PRC’s economic and ideological redevelopment.

Consequences

The split, seen by historians as one of the key events of the Cold War, had massive consequences for the two powers and for the world. The USSR had a network of communist parties it supported. China created its own rival network to battle it out for local control of the left in numerous countries. The divide fractured the international communist movement at the time and opened the way for the warming of relations between the U.S. and China under Richard Nixon and Mao in 1971.

In China, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), largely to prevent the development of Russian-style bureaucratic communism of the USSR. The ideological split also escalated to small-scale warfare between Russia and China, with a revived conflict over the Russo-Chinese border demarcated in the 19th century (starting in 1966) and Red Guards attacking the Soviet embassy in Beijing (1967). In the 1970s, Sino-Soviet ideological rivalry extended to Africa and the Middle East, where the Soviet Union and China funded and supported opposed political parties, militias, and states.

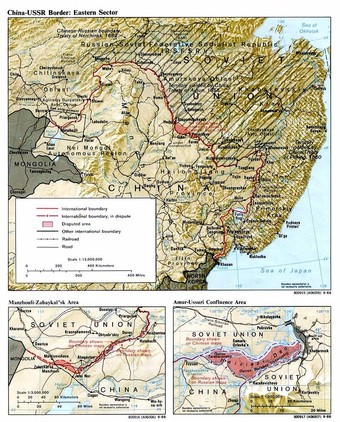

The disputed Argun and Amur river areas; the Damansky–Zhenbao is southeast, north of the lake. (March 2 – September 11, 1969). Source: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection. By March 1969, Sino-Russian border politics became the Sino-Soviet border conflict at the Ussuri River and on Damansky–Zhenbao Island, with more small-scale warfare occurring at Tielieketi in August.

After the regime of Mao Zedong, the PRC–USSR ideological schism no longer shaped domestic politics but continued to impact geopolitics. The initial Soviet-Chinese proxy war occurred in Indochina in 1975, where the Communist victory of the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) and of North Vietnam in the 30-year Vietnam War had produced a post–colonial Indochina that featured pro-Soviet regimes in Vietnam (Socialist Republic of Vietnam) and Laos (Lao People’s Democratic Republic), and a pro-Chinese regime in Cambodia (Democratic Kampuchea). At first, Vietnam ignored the Khmer Rouge domestic reorganization of Cambodia by the Pol Pot regime (1975–79) as an internal matter, until the Khmer Rouge attacked the ethnic Vietnamese populace of Cambodia and the border with Vietnam. The counter-attack precipitated the Cambodian-Vietnamese War (1975–79) that deposed Pol Pot in 1978. In response, the PRC denounced the Vietnamese and retaliated by invading northern Vietnam in the Sino-Vietnamese War (1979). In turn, the USSR denounced the PRC’s invasion of Vietnam. In 1979, the USSR invaded the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan to sustain the Afghan Communist government. The PRC viewed the Soviet invasion as a local feint within Soviet’s greater geopolitical encirclement of China. In response, the PRC entered a tripartite alliance with the U.S. and Pakistan to sponsor Islamist Afghan armed resistance to the Soviet occupation (1979–89).

Relations between China and the Soviet Union remained tense until the visit of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to Beijing in 1989.

Attributions

- The Sino-Soviet Split

-

“On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On_the_Cult_of_Personality_and_Its_Consequences. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Hundred Flowers Campaign.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hundred_Flowers_Campaign. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Five-year plans for the national economy of the Soviet Union.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five-year_plans_for_the_national_economy_of_the_Soviet_Union. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Mao_Tsé-toung_portrait_en_buste_assis_faisant_face_à_Nikita_Khrouchtchev_pendant_la_visite_du_chef_russe_1958_à_Pékin.jpg.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Soviet_split#/media/File:Mao_Ts%C3%A9-toung,_portrait_en_buste,_assis,_faisant_face_%C3%A0_Nikita_Khrouchtchev,_pendant_la_visite_du_chef_russe_1958_%C3%A0_P%C3%A9kin.jpg. Wikipedia Public domain.

-

“800px-China_USSR_E_88.jpg.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Soviet_split#/media/File:China_USSR_E_88.jpg. Wikipedia Public domain.

Candela Citations

- Boundless World History. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/. License: CC BY: Attribution