35.5.5: Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia (1975-1979) introduced an extreme governing system based on the relocation of urban residents to rural areas and halting nearly all economic, social, and cultural activities. It was responsible for mass atrocities known as the Cambodian genocide.

Learning Objective

Summarize the crimes perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge

Key Points

- The history of the Khmer Rouge is tied to the history of the communist movement in Indochina. In 1951, the Indochinese Communist Party was reorganized into three national units — the Vietnam Workers’ Party, the Lao Issara (in Laos), and the Kampuchean (or Khmer) People’s Revolutionary Party. However, during the 1950s, Khmer students in Paris organized their own communist movement. From their ranks came the men and women who returned home and took command of the party apparatus during the 1960s, led an effective insurgency against Lon Nol from 1968 until 1975, and established the regime of Democratic Kampuchea under the leadership of Pol Pot.

- In 1968, the Khmer Rouge was officially formed and its forces launched a national insurgency across Cambodia. Vietnamese support for the insurgency made it impossible for the Cambodian military to effectively counter it. For the next two years the insurgency grew as Prince Sihanouk, head of Cambodia, did very little to stop it. The political appeal of the Khmer Rouge increased after the removal of Sihanouk as head of state in 1970 by Premier Lon Nol. Sihanouk, in exile in Beijing, made an alliance with the Khmer Rouge, after which their ranks swelled from 6,000 to 50,000 fighters. Many of the new recruits for the Khmer Rouge were apolitical peasants who fought in support of the Prince, not for communism. On April 17, 1975 the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh.

- The Khmer Rouge carried out a radical program that included isolating the country from all foreign influences, closing schools, hospitals, and factories, abolishing banking, finance, and currency, outlawing all religions, confiscating all private property and relocating people from urban areas to collective farms, where forced labor was widespread. The purpose of this policy was to turn Cambodians into “Old People” (as opposed the urban populations known as “New People”) through agricultural labor.

- Money was abolished, books were burned, and teachers, merchants, and almost the entire intellectual elite of the country were murdered to make the agricultural communism, as Pol Pot envisioned it, a reality. The planned relocation to the countryside resulted in the complete halting of almost all economic activity.

- In 1978, Pol Pot, fearing a Vietnamese attack, ordered a pre-emptive invasion of Vietnam. At the end of the same year, the Vietnamese armed forces, along with the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation, an organization that included many dissatisfied former Khmer Rouge members, invaded Cambodia and captured Phnom Penh in January 1979.

- The Khmer Rouge government arrested, tortured, and eventually executed anyone suspected of belonging to several categories of supposed “enemies.” Various studies have estimated the death toll at between 740,000 and 3 million most commonly between 1.4 million and 2.2 million, with perhaps half of those deaths due to executions and the rest from starvation and disease. Because of the intense opposition to the Vietnam War, for years many Western scholars denied the genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge regime.

Key Terms

- Democratic Kampuchea

- The name of the Khmer Rouge-controlled state that between 1975 and 1979 existed in present-day Cambodia. It was founded when the Khmer Rouge forces defeated the Khmer Republic of Lon Nol in 1975. During its rule between 1975 and 1979, the state and its ruling Khmer Rouge regime was responsible for the deaths of millions of Cambodians through forced labor and genocide. After losing control of most of Cambodian territory to Vietnamese occupation, it survived as a rump state supported by China.

- Cambodian Genocide

- Mass attrocities carried out by the Khmer Rouge regime led by Pol Pot between 1975 and 1979, in which an estimated 1.5 to 3 million people died.

- Khmer Rouge

- The name given to the followers of the Communist Party of Kampuchea in Cambodia. It was formed in 1968 as an offshoot of the Vietnam People’s Army from North Vietnam, and allied with North Vietnam, the Viet Cong, and Pathet Lao during the Vietnam War against the anti-communist forces from 1968 to 1975.

Khmer Rouge: Rise to Power

The history of the Khmer Rouge is tied to the history of the communist movement in Indochina. In 1951, the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) was reorganized into three national units — the Vietnam Workers’ Party, the Lao Issara (in Laos), and the Kampuchean (or Khmer) People’s Revolutionary Party (KPRP). According to a document issued after the reorganization, the Vietnam Workers’ Party would continue to “supervise” the smaller Laotian and Cambodian movements. Most KPRP leaders and rank-and-file seem to have been either Khmer Krom, or ethnic Vietnamese living in Cambodia. The party’s appeal to indigenous Khmers appears to have been minimal.

During the 1950s, Khmer students in Paris organized their own communist movement, which had little if any connection to the hard-pressed party in their homeland. From their ranks came the men and women who returned home and took command of the party apparatus during the 1960s, led an effective insurgency against Lon Nol from 1968 until 1975, and established the regime of Democratic Kampuchea. Some members of the Paris group, most notably Pol Pot and Ieng Sary, turned to Marxism-Leninism and joined the French Communist Party. In 1951, the two men went to East Berlin to participate in a youth festival. This experience is considered a turning point in their ideological development. Meeting with Khmers who were fighting with the Viet Minh, they became convinced that only a tightly disciplined party organization and a readiness for armed struggle could achieve revolution. They transformed the Khmer Students Association (KSA), to which most of the 200 or so Khmer students in Paris belonged, into an organization for nationalist and leftist ideas. After returning to Cambodia in 1953, Pol Pot threw himself into party work.

In 1960, 21 leaders of the KPRP held a secret congress in a vacant room of the Phnom Penh railroad station. This pivotal event remains shrouded in mystery because its outcome has become an object of contention (and considerable historical rewriting) between pro-Vietnamese and anti-Vietnamese Khmer communist factions. The question of cooperation with or resistance to Prince Sihanouk (head of the Cambodian state) was thoroughly discussed. The KPRP was renamed the Workers’ Party of Kampuchea (WPK).

In 1962, Tou Samouth, the WPK secretary, was murdered by the Cambodian government. A year later, Pol Pot was chosen to succeed Tou Samouth as the party’s general secretary. Pol Pot was also put on a list of 34 leftists who were summoned by Sihanouk to join the government and sign statements saying Sihanouk was the only possible leader for the country. Pol Pot and one more leader, Chou Chet, were the only people on the list who escaped. The region where Pol Pot moved to was inhabited by tribal minorities, the Khmer Loeu, whose rough treatment (including resettlement and forced assimilation) at the hands of the central government made them willing recruits for a guerrilla struggle. In 1965, Pol Pot made a visit of several months to North Vietnam and China.

In 1968, the Khmer Rouge was officially formed and its forces launched a national insurgency across Cambodia. Although North Vietnam had not been informed of the decision, its forces provided shelter and weapons to the Khmer Rouge after the insurgency started. Vietnamese support for the insurgency made it impossible for the Cambodian military to effectively counter it. For the next two years the insurgency grew as Sihanouk did very little to stop it. As the insurgency grew stronger, the party finally openly declared itself to be the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK).

The political appeal of the Khmer Rouge increased as a result of the situation created by the removal of Sihanouk as head of state in 1970. Premier Lon Nol, with the support of the National Assembly, deposed Sihanouk. Sihanouk, in exile in Beijing, made an alliance with the Khmer Rouge and became the nominal head of a Khmer Rouge-dominated government-in-exile (known by its French acronym, GRUNK) backed by China. After Sihanouk showed his support for the Khmer Rouge by visiting them in the field, their ranks swelled from 6,000 to 50,000 fighters. Many of the new recruits for the Khmer Rouge were apolitical peasants who fought in support of the Prince, not for communism. Sihanouk’s popular support in rural Cambodia allowed the Khmer Rouge to extend its power and influence to the point that by 1973 it exercised de facto control over the majority of Cambodian territory, although only a minority of its population. Many people in Cambodia who helped the Khmer Rouge against the Lon Nol government thought they were fighting for the restoration of Sihanouk. By 1975, with the Lon Nol government running out of ammunition, it was clear that it was only a matter of time before the government would collapse. On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh.

Khmer Rouge Regime

The Khmer Rouge carried out a radical program that included isolating the country from all foreign influences; closing schools, hospitals, and factories, abolishing banking, finance, and currency; outlawing all religions; confiscating all private property; and relocating people from urban areas to collective farms where forced labor was widespread. The purpose of this policy was to turn Cambodians into “Old People” (as opposed the urban populations known as “New People”) through agricultural labor.

The Khmer Rouge attempted to turn Cambodia into a classless society by depopulating cities. The entire population was forced to become farmers in labor camps. The total lack of agricultural knowledge by the former city dwellers made famine inevitable. Rural dwellers were often unsympathetic or too frightened to assist them. Such acts as picking wild fruit or berries were seen as “private enterprise” and punished by death. The Khmer Rouge forced people to work for 12 hours, without adequate rest or food. These actions resulted in massive deaths through executions, work exhaustion, illness, and starvation. Commercial fishing was banned in 1976, resulting in a loss of primary food sources for millions of Cambodians, 80% of whom rely on fish as their only source of animal protein.

Money was abolished, books were burned, and teachers, merchants, and almost the entire intellectual elite of the country were murdered to make the agricultural communism as Pol Pot envisioned it a reality. The planned relocation to the countryside resulted in the complete halting of almost all economic activity.

All religion was banned. Any people seen taking part in religious rituals or services were executed. Thousands of Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians were killed for exercising their beliefs. Family relationships not sanctioned by the state were also banned and family members could be put to death for communicating with each other. Married couples were only allowed to visit each other on a limited basis. If people were seen engaged in sexual activity, they would be killed immediately. In many cases, family members were relocated to different parts of the country with all postal and telephone services abolished.Almost all freedom to travel was abolished. Almost all privacy was eliminated. People were not even allowed to eat in privacy. Instead, they were required to eat with everyone in the commune.

Fall of Khmer Rouge Regime

In 1978, Pol Pot, fearing a Vietnamese attack, ordered a pre-emptive invasion of Vietnam. At the end of the same year, the Vietnamese armed forces, along with the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation, an organization that included many dissatisfied former Khmer Rouge members, invaded Cambodia and captured Phnom Penh in January 1979. Despite a traditional Cambodian fear of Vietnamese domination, defecting Khmer Rouge activists assisted the Vietnamese and with Vietnam’s approval became the core of the new People’s Republic of Kampuchea. At the same time, the Khmer Rouge retreated west and continued to control certain areas near the Thai border for the next decade. The Khmer Rouge survived into the 1990s as a resistance movement operating in western Cambodia from bases in Thailand. In 1996, following a peace agreement, Pol Pot formally dissolved the organization. He died in 1998, having never been put on trial. Today, Cambodia is officially a multiparty democracy but in reality, it is a communist-party state dominated by Prime Minister Hun Sen, a recast Khmer Rouge official in power since 1985.

Cambodian Genocide

The Khmer Rouge government arrested, tortured, and eventually executed anyone suspected of belonging to several categories of supposed “enemies,” including anyone with connections to the former Cambodian government or with foreign governments, professionals and intellectuals, ethnic Vietnamese, Chinese, Thai, and other minorities in the Eastern Highlands, Cambodian Christians, Muslims, and Buddhist monks, and “economic saboteurs” – a category that included many former urban dwellers deemed guilty of sabotage due to their lack of agricultural ability. Those who were convicted of treason were taken to a top-secret prison called S-21. The prisoners were rarely given food and, as a result, many people died of starvation. Others died from the severe physical mutilation caused by torture.

Modern research has located 20,000 mass graves from the Khmer Rouge era all over Cambodia. Various studies have estimated the death toll at between 740,000 and 3 million, most commonly between 1.4 million and 2.2 million, with perhaps half of those deaths due to executions and the rest from starvation and disease. The Cambodian Genocide Program at Yale University estimates the number of deaths at approximately 1.7 million (21% of the population of the country). A UN investigation reported 2–3 million dead, while UNICEF estimates that 3 million had been killed. An additional 300,000 Cambodians starved to death between 1979 and 1980, largely as a result of the after-effects of Khmer Rouge policy.

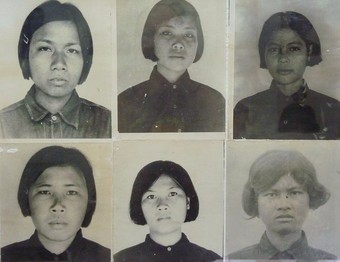

Rooms of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum commemorating the Cambodian genocide contain thousands of photos taken by the Khmer Rouge of their victims. The Khmer Rouge regime targeted various ethnic groups during the genocide, forcibly relocated minority groups, and banned the use of minority languages. The Khmer Rouge banned by decree the existence of ethnic Chinese, Vietnamese, Muslim Cham, and 20 other minorities, which altogether constituted 15% of the population at the beginning of the Khmer Rouge’s rule.

Because of the intense opposition to the Vietnam War, particularly among Western intellectuals, many Western scholars denied the genocide perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge regime. Despite the eye-witness accounts by journalists prior to their expulsion during the first few days of Khmer Rouge rule and the later testimony of refugees, many academics in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Australia, and other countries portrayed the Khmer Rouge favorably or at least were skeptical about the stories of Khmer Rouge atrocities. None of them, however, were allowed to visit Cambodia under Khmer Rouge rule and few actually talked to the refugees whose stories they believed to be exaggerated or false. Some Western scholars believed that the Khmer Rouge would free Cambodia from colonialism, capitalism, and the ravages of American bombing and invasion during the Vietnam War. Cambodian scholar Sophal Ear has titled the pro-Khmer Rouge academics as the “Standard Total Academic View on Cambodia” (STAV).

With the takeover of Cambodia by Vietnam in 1979 and the discovery of incontestable evidence, the Khmer Rouge atrocities proved to be entirely accurate. Some former enthusiasts for the Khmer Rouge recanted their previous views, others diverted their interest to other issues, and a few continued to defend the Khmer Rouge. A few months before his death in 1998, Nate Thayer interviewed Pol Pot. During the interview, Pol Pot stated that he had a clear conscience and denied responsible for the genocide. In 2013, the Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen passed legislation that makes the denial of the Cambodian genocide and other war crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge illegal.

Attributions

- Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge

-

“Cambodian genocide denial.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodian_genocide_denial. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Photos_of_victims_in_Tuol_Sleng_prison.JPG.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Photos_of_victims_in_Tuol_Sleng_prison.JPG. Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

Candela Citations

- Boundless World History. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/. License: CC BY: Attribution