35.2.3: The American-Japanese Relationship

Japan has remained one of the strongest and most reliable allies of the United States since the post-World War II occupation of the country by the Allied forces, despite ongoing tensions over the U.S. military presence on Japanese territories and economic competition between the two countries.

Learning Objective

Evaluate American-Japanese relations

Key Points

- The San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed in 1951, marked the end of the Allied occupation of Japan. The treaty served to officially end Japan’s position as an imperial power, allocate compensation to Allied civilians and former prisoners of war who suffered Japanese war crimes during World War II, and return sovereignty to Japan. In legal terms, the end of the occupation finally placed Japan’s relations with the United States on an equal footing, but this equality was initially largely nominal.

- As the disastrous results of World War II subsided into the background and trade with the United States expanded, Japan’s self-confidence grew, which gave rise to a desire for greater independence from United States influence. During the 1950s and 1960s, this was especially evident in the Japanese attitude toward U.S. military bases on the four main islands of Japan and in Okinawa Prefecture.

- Recognizing the popular desire for the return of the Ryukyu Islands and the Bonin Islands, in 1953 the United States relinquished its control of the Amami group of islands at the northern end of the Ryukyu Islands. However, it made no commitment to return Okinawa. Popular agitation culminated in a unanimous resolution adopted by the Diet in 1956, calling for a return of Okinawa to Japan.

- Under a new 1960 treaty, both parties assumed an obligation to assist each other in case of armed attack on territories under Japanese administration. The treaty also included general provisions on the further development of international cooperation and improved future economic cooperation. Both countries worked closely to fulfill the United States promise to return all Japanese territories acquired in war. In 1968, the United States returned the Bonin Islands to Japanese administration control. In 1971, the two countries signed an agreement for the return of Okinawa to Japan in 1972.

- A series of 1971 events marked the beginning of a new stage in relations, a period of adjustment to a changing world situation. Despite episodes of strain in both political and economic spheres, the basic relationship remained close. The political issues were essentially security-related. The economic issues tended to stem from the ever-growing power of the Japanese economy. In the 1980s, particularly during the Reagan years, the relationship improved and strengthened. More recently, it has gained new urgency in light of the changing global positions of North Korea and China.

- The American military bases on Okinawa have caused challenges, as Japanese and Okinawans have protested their presence for decades. In secret negotiations that began in 1969, Washington sought unrestricted use of its bases for possible conventional combat operations in Korea, Taiwan, and South Vietnam as well as the emergency re-entry and transit rights of nuclear weapons. In the end, the United States and Japan agreed to maintain bases that would allow the continuation of American deterrent capabilities in East Asia.

Key Terms

- Japan Self-Defense Forces

- The unified military forces of Japan established in 1954 and controlled by the Ministry of Defense. In recent years, they have been engaged in international peacekeeping operations including UN peacekeeping. Recent tensions, particularly with North Korea, have reignited the debate over their status and relation to Japanese society.

- San Francisco Peace Treaty

- A treaty predominantly between Japan and the Allied Powers but officially signed by 48 nations on September 8, 1951, in San Francisco, California. It came into force on April 28, 1952, and served to end Japan’s position as an imperial power, allocate compensation to Allied civilians and former prisoners of war who suffered Japanese war crimes during World War II, and end the Allied post-war occupation of and return sovereignty to Japan.

- Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution

- A clause outlawing war to settle international disputes involving the state. The Constitution came into effect on May 3, 1947, following World War II. In its text, the state formally renounces the sovereign right of belligerency and aims at an international peace based on justice and order.

Unequal Post-War Relations

The San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on September 8, 1951, marked the end of the Allied occupation in Japan. When it went into effect on April 28, 1952, Japan was once again an independent state and an ally of the United States. The treaty officially ended Japan’s position as an imperial power, allocated compensation to Allied civilians and former prisoners of war who suffered Japanese war crimes during World War II, and returned sovereignty to Japan. It made extensive use of the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to enunciate the Allies’ goals.

In legal terms, the end of the occupation finally placed Japan’s relations with the United States on equal footing, but this equality was initially largely nominal. As the disastrous results of World War II subsided and trade with the United States expanded, Japan’s self-confidence grew, which gave rise to a desire for greater independence from United States influence. During the 1950s and 1960s, this feeling was evident in the Japanese attitude toward United States military bases on the four main islands of Japan and in Okinawa Prefecture, occupying the southern two-thirds of the Ryukyu Islands.

The government had to balance left-wing pressure advocating dissociation from the United States with the claimed need for military protection. Recognizing the popular desire for the return of the Ryukyu Islands and the Bonin Islands (also known as the Ogasawara Islands), in 1953 the United States relinquished its control of the Amami group of islands at the northern end of the Ryukyu Islands. However, it made no commitment to return Okinawa, which was then under United States military administration for an indefinite period as provided in Article 3 of the peace treaty. Popular agitation culminated in a unanimous resolution adopted by Japan’s legislature in 1956, calling for a return of Okinawa to Japan.

Military Alliance and New Challenges

Bilateral talks on revising the 1952 security pact began in 1959, and the new Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security was signed, despite the protests of left-wing political parties and mass demonstrations, in Washington in 1960. Under the new treaty, both parties assumed an obligation to assist each other in case of armed attack on territories under Japanese administration. It was understood, however, that Japan could not come to the defense of the United States because it was constitutionally forbidden to send armed forces overseas under Article 9 of its Constitution. The scope of the new treaty did not extend to the Ryukyu Islands, but an appended minute made clear that in case of an armed attack on the islands, both governments would consult and take appropriate action. Unlike the 1952 security pact, the new treaty provided for a ten-year term, after which it could be revoked upon one year’s notice by either party. The treaty included general provisions on the further development of international cooperation and improved future economic cooperation.

Both countries worked closely to fulfill the United States promise, under Article 3 of the peace treaty, to return all Japanese territories acquired in war. In 1968, the United States returned the Bonin Islands (including Iwo Jima) to Japanese administration control. In 1971, after eighteen months of negotiations, the two countries signed an agreement for the return of Okinawa to Japan in 1972.

A series of new issues arose in 1971. First, Nixon’s dramatic announcement of his forthcoming visit to the People’s Republic of China surprised the Japanese. Many were distressed by the failure of the United States to consult in advance with Japan before making such a fundamental change in foreign policy. Second, the government was again surprised to learn that without prior consultation, the United States had imposed a 10 percent surcharge on imports, a decision certain to hinder Japan’s exports to the United States. Relations between Tokyo and Washington were further strained by the monetary crisis involving the revaluation of the Japanese yen.

These events marked the beginning of a new stage in relations, a period of adjustment to a changing world situation that was not without episodes of strain in both political and economic spheres, although the basic relationship remained close. The political issues between the two countries were essentially security-related and derived from efforts by the United States to induce Japan to contribute more to its own defense and regional security. The economic issues tended to stem from the ever-widening United States trade and payments deficits with Japan, which began in 1965 when Japan reversed its imbalance in trade with the United States and for the first time achieved an export surplus. Heavy American military spending in the Korean War (1950–53) and the Vietnam War (1965–73) provided a major stimulus to the Japanese economy.

New Global Factors

The United States withdrawal from Indochina in 1975 and the end of the Vietnam War meant that the question of Japan’s role in the security of East Asia and its contributions to its own defense became central in the dialogue between the two countries. The Japanese government, constrained by constitutional limitations and strongly pacifist public opinion, responded slowly to U.S. pressures for a more rapid buildup of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF). It steadily increased its budgetary outlays for those forces, however, and indicated its willingness to shoulder more of the cost of maintaining the United States military bases in Japan. In 1976, the United States and Japan formally established a subcommittee for defense cooperation, and military planners of the two countries conducted studies relating to joint military action in the event of an armed attack on Japan.

Under American pressure Japan worked toward a comprehensive security strategy with closer cooperation with the United States for a more reciprocal and autonomous basis. This policy was put to the test in 1979, when radical Iranians seized the United States embassy in Tehran, taking 60 hostages. Japan reacted by condemning the action as a violation of international law. At the same time, Japanese trading firms and oil companies reportedly purchased Iranian oil that became available when the United States banned oil imported from Iran. This action brought sharp criticism from the U.S. of Japanese government “insensitivity” for allowing the oil purchases and led to a Japanese apology and agreement to participate in sanctions against Iran in concert with other allies.

Following that incident, the Japanese government took greater care to support U.S. international policies designed to preserve stability and promote prosperity. Japan was prompt and effective in announcing and implementing sanctions against the Soviet Union following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. In 1981, in response to United States requests, it accepted greater responsibility for defense of seas around Japan, pledged greater support for United States forces in Japan, and persisted with a steady buildup of the JSDF.

Close Ties and New Challenges

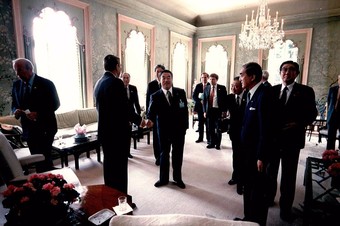

A qualitatively new stage of Japan-United States cooperation in world affairs emerged in the 1980s with the election of Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, who enjoyed a particularly close relationship with Ronald Reagan. Nakasone reassured U.S. leaders of Japan’s determination against the Soviet threat, closely coordinated policies with the United States toward such Asian trouble spots as the Korean Peninsula and Southeast Asia, and worked cooperatively with the United States in developing China policy. The Japanese government welcomed the increase of United States forces in Japan and the western Pacific, continued the steady buildup of the JSDF, and positioned Japan firmly on the side of the United States against the threat of Soviet expansion. Japan continued to cooperate closely with United States policy in these areas following Nakasone’s term of office, although the political leadership scandals in Japan in the late 1980s made it difficult for newly elected President George H. W. Bush to establish the close personal ties that marked the Reagan years. Despite complaints from some Japanese businesses and diplomats, the Japanese government remained in basic agreement with U.S. policy toward China and Indochina. The government held back from large-scale aid efforts until conditions in China and Indochina were seen as more compatible with Japanese and U.S. interests.

Ronald Reagan greeting Japanese leaders, including Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, Foreign Minister Abe, and Finance Minister Takashita, in London in 1984. Picture of the Ronald Reagan administration worked closely with their Japanese counterparts to develop a personal relationship between the two leaders based on their common security and international outlook. Nakasone backed Reagan to deploy Pershing missiles in Europe at the 1983 9th G7 summit. In 1983, a U.S.-Japan working group produced the Reagan-Nakasone Joint Statement on Japan-United States Energy Cooperation.

The main area of noncooperation with the United States in the 1980s was Japanese resistance to repeated U.S. efforts to get Japan to open its market to foreign goods and change other economic practices seen as adverse to U.S. economic interests. Furthermore, changing circumstances at home and abroad created a crisis in Japan-United States relations in the late 1980s. Japan’s growing investment in the United States—the second largest investor after Britain—led to complaints from some American constituencies. Moreover, Japanese industry seemed well-positioned to use its economic power to invest in high-technology products, in which United States manufacturers were still leaders. The United States’s ability to compete under these circumstances was seen by many Japanese and Americans as hampered by heavy personal, government, and business debt and a low savings rate. The breakup of the Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe forced the Japanese and United States governments to reassess their longstanding alliance against the Soviet threat. Some Japanese and United States officials and commentators continued to emphasize the common dangers to Japan-United States interests posed by the continued strong Soviet military presence in Asia.

Since the late 1990s, the U.S.-Japan relationship has improved and strengthened. The major cause of friction in the relationship, trade disputes, became less problematic as China displaced Japan as the greatest perceived economic threat to the United States. Meanwhile, although in the immediate post-Cold War period the security alliance suffered from a lack of a defined threat, the emergence of North Korea as a belligerent rogue state and China’s economic and military expansion provided a purpose to strengthen the relationship. While the foreign policy of the administration of President George W. Bush put a strain on some of the United States’ international relations, the alliance with Japan became stronger, as evidenced by the Deployment of Japanese troops to Iraq and the joint development of anti-missile defense systems.

The Okinawa Controversy

Okinawa is the site of major American military bases that have caused problems, as Japanese and Okinawans have protested their presence for decades. In secret negotiations that began in 1969, Washington sought unrestricted use of its bases for possible conventional combat operations in Korea, Taiwan, and South Vietnam as well as the emergency re-entry and transit rights of nuclear weapons. However, anti-nuclear sentiment was strong in Japan and the government wanted the United States to remove all nuclear weapons from Okinawa. In the end, the United States and Japan agreed to maintain bases that would allow the continuation of American deterrent capabilities in East Asia. When the Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa, reverted to Japanese control in 1972, the United States retained the right to station forces on these islands. A dispute that had boiled since 1996 regarding a base with 18,000 U.S. Marines was temporarily resolved in late 2013. Agreement was reached to move the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to a less-densely populated area of Okinawa.

U.S. military bases in Japan: US military bases in Japan, maintained by the U.S. government as a way to mark the U.S. presence in the Pacific, continue to provoke protests among the Japanese.

As of 2014, the United States still had 50,000 troops in Japan, the headquarters of the U.S. 7th Fleet, and more than 10,000 Marines. Also in 2014, it was revealed the United States was deploying two unarmed Global Hawk long-distance surveillance drones to Japan with the expectation they would engage in surveillance missions over China and North Korea.

Attributions

- The American-Japanese Relationship

-

“Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Article_9_of_the_Japanese_Constitution. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Treaty of San Francisco.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_San_Francisco. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Japan–United States relations.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japan%E2%80%93United_States_relations. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“Japan Self-Defense Forces.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japan_Self-Defense_Forces. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“1280px-Reagan_Japanese_Meetings_London_1984.jpg.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Reagan_Japanese_Meetings_London_1984.jpg. Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

“525px-US_Military_bases_in_Japan.jpg.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_Military_bases_in_Japan.jpg. Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

-

Candela Citations

- Boundless World History. Authored by: Boundless. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/. License: CC BY: Attribution