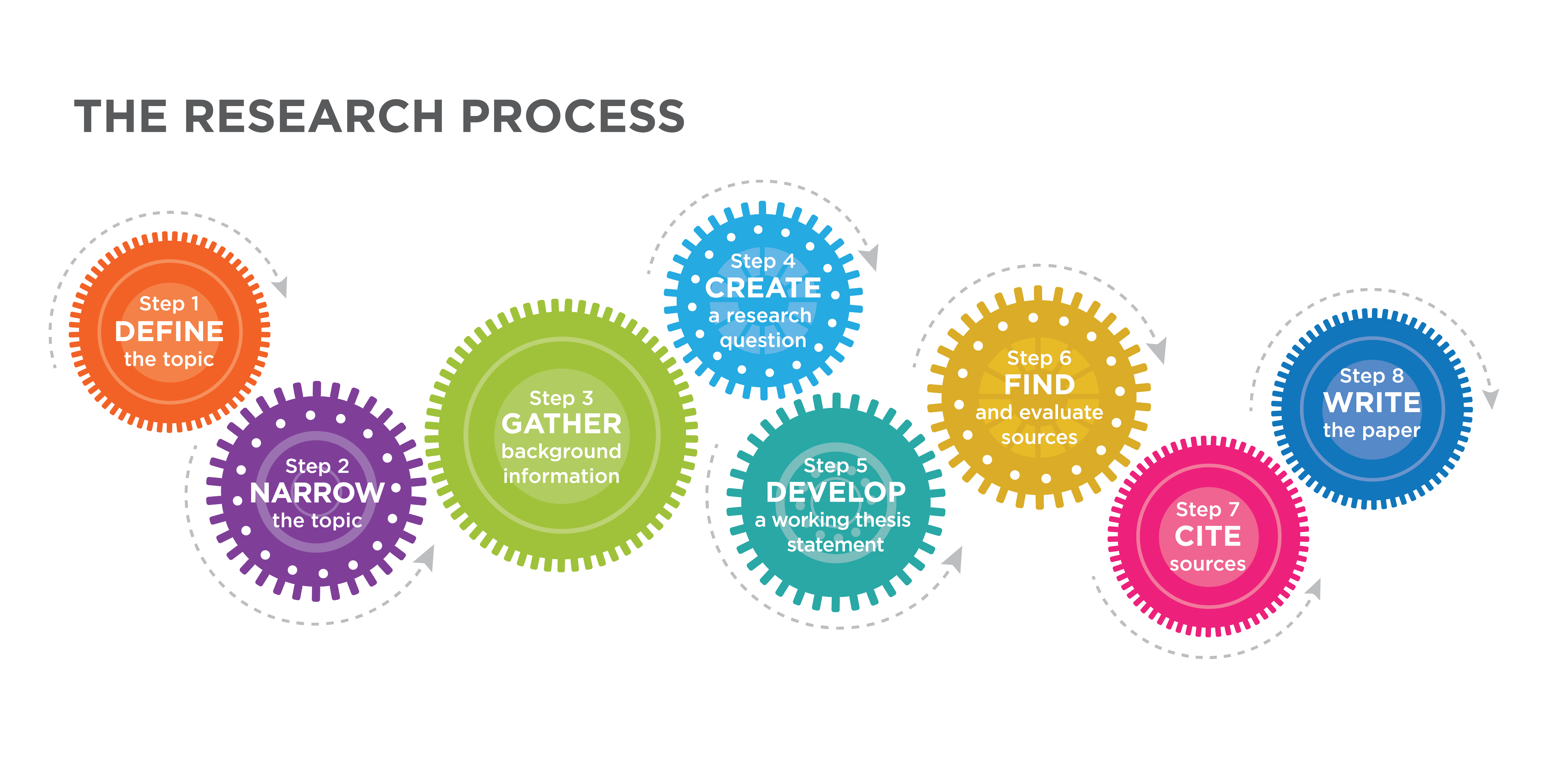

The research process is not a linear process in which you must complete step one before moving on to step two or three. You don’t need to put off writing your paper until you’ve gathered all of your sources, in fact, you may want to start writing as soon as possible and adjust your search, thesis statement, and writing as you continue to work through the research process. For that reason, consider the following research process as a guideline to follow as your work through your paper. You can (and should!) revisit the steps as many times as needed to create a finished product.

- Decide on the topic, or carefully consider the topic that has been assigned.

- Narrow the topic in order to narrow search parameters. When you go to a professional sports event, concert, or event at a large venue, your ticket has three items on it: the section, the row, and the seat number. You go in that specific order to pinpoint where you are supposed to sit. Similarly, when you decide on a topic, you often start large and must narrow the focus; you move from general subject, to a more limited topic, to a specific focus or issue. The reader does not want a cursory look at the topic; she wants to walk away with some newfound knowledge and deeper understanding of the issue. For that, details are essential. For example, suppose you want to explore the topic of autism. You might move from:

- General topic: special needs in a classroom

- Limited topic: autistic students in a classroom setting

- Specific focus: how technology can enhance learning for autistic students

- Do background research, or pre-research. Begin by figuring out what you know about the topic, and then fill in any gaps you may have on the basics by looking at more general sources. This is a place where general Google searches, Wikipedia, or another encyclopedia-style source will be most useful. Once you know the basics of the topic, start investigating that basic information for potential sources of conflict. Does there seem to be disagreement about particular aspects of the topic? For instance, if you’re looking at a Civil War battle, are there any parts of the battle that historians seem to argue about? Perhaps some point to one figure’s failing as a reason for a loss, and some point instead to another figure’s spectacular success as a reason his side won?

- Create a research question. Once you have narrowed your topic so that is manageable, it is time to generate research questions about your topic. Create thought-provoking, open-ended questions, ones that encourage debate. Decide which question addresses the issue that concerns you—that will be your main research question. Secondary questions will address the who, what, when, where, why, and how of the issue. As an example:

- Main question: Does the media stereotype women in such a way that women do not believe they can be leaders?

- Secondary questions: How can more women get involved in politics? Why aren’t more women involved in politics? What role do media play in discouraging women from being involved? How many women are involved in politics at a state or national level? How long do they typically stay in politics, and for what reasons do they leave?

- Next, “answer” the main research question to create a working thesis statement. The thesis statement is a single sentence that identifies the topic and shows the direction of the paper while simultaneously allowing the reader to glean the writer’s stance on that topic. A working thesis performs four main functions:

- Narrows the subject to the single point that readers should understand

- Names the topic and makes a significant assertion about that topic

- Conveys the purpose

- Provides a preview of how the essay will be arranged (usually).

- Determine what kind of sources are best for your argument.

- How many sources will you need? How long should your paper be? Will you need primary or secondary sources? Where will you find the best information?

- Create a bibliography as you gather and reference sources. Make sure you are using credible and relevant sources. It’s always a good idea to utilize reference management programs like Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote so you can keep track of your research and citations while you are working and searching, instead of waiting until the end.

- Write and edit your paper! Lastly, you’ll incorporate the research into your own writing and properly cite your sources.

Practice: Research Questions and Working Thesis Statements

1. Which of the following is the better research question?

-

- How does trash pollute the environment?

- What is the environmental impact of plastic water bottles?

- What is the impact of bottled water on the environment?

2. Decide whether or not the following working thesis statements are good or bad:

-

-

- Man has had a major impact on the environment.

- Marijuana use in Mishawaka, Indiana has been a problem for law enforcement since the 1970s.

- Miley Cyrus is a horrible singer.

- Profilers have played a necessary role in catching serial killers.

-

Finding Items for a Topic

Today, the commonplace books that rhetoricians once maintained to organize and develop topics for their own use have been replaced by books, libraries, television, radio, and the Internet. A lot of the work done by people in the media, government, business, and academia comes down to taming the flow of information that’s now faster than ever. As an academic reader and writer, you’re joining that effort. One of your goals should be to become a critical thinker and writer who possesses the skills to organize, explore, and develop topics on your own. You can gain those skills with practice. Lots of practice.

To help that practice, you can use some tools you’re already familiar with and some others that may be new to you.

Students sometimes believe they really don’t know what to write and argue about. When the Internet was developing a few years ago as a  common communication medium, a lot of commentators believed it would make being an informed researcher and citizen easier: after all, having access to the Internet means having access to more information than anyone has ever had access to before in human history. But the problem is that having access to the Internet means having access to more information than anyone has ever had access to before in human history. To start looking for and working with a topic, for instance, your first inclination might be to use Google and simply “search” for a term. If we tried to look for information on voting laws, though, we’d get a return of over 32,000,000 items in less than a second.

common communication medium, a lot of commentators believed it would make being an informed researcher and citizen easier: after all, having access to the Internet means having access to more information than anyone has ever had access to before in human history. But the problem is that having access to the Internet means having access to more information than anyone has ever had access to before in human history. To start looking for and working with a topic, for instance, your first inclination might be to use Google and simply “search” for a term. If we tried to look for information on voting laws, though, we’d get a return of over 32,000,000 items in less than a second.

There are two problems with this approach (at least).

First, the quality of the items should cause us some doubt. This basic search returns wikipedia articles, news stories, government agency sources, and even a non-profit organization website. While some of these might be helpful, the items have neither given us a detailed “place” to begin our topic nor a clear “place” to stand.

Our second problem concerns the amount of information. We just can’t sift through 32 million items, so we need a tool that does some of the selecting and organizing for us. Google News (https://news.google.com/) is one example of just such a tool. This site allows us to better focus on a topic as it unfolds in real time. If we use our “voting laws” search term, Google News and its “Realtime Coverage” option posts the most recent news articles in the subject, provides investigative “in depth” articles, makes available opinion pieces, and even includes a timeline for articles published on the topic. These features give us places for specific types of items, and they help us because they are already loosely organized and defined.

Next Steps

Sites like Google News are great places to begin research on a topic because they provide a range of different types of items and a helpful model for how to organize those items. On the other hand, these sites are bad places to end your research. Google News, for instance, does not capture scholarly resources. These sources are often vital to provide even more in-depth and focused coverage on topics.

For the purposes of beginning your research topic, however, selecting a range of articles from an array of sources will help you explore the various “places” contained in any topic. For instance, a typical news story is usually brief and only has room to offer minimal information. The common topics most likely to occur here are those best used to communicate basic facts: cause-effect, definition, and/or antecedent/consequence. An investigative journalism essay, a longer piece taking much more time to develop and much more space for coverage, will be better suited for more nuanced kinds of common topics such as contradictions, limits, and/or similarity/difference. More particular examples, such as YouTube videos of a politician’s speeches, might offer exposure to those “special topics” found in deliberative, judicial, and ceremonial discourses. Opinion essays or “op-eds” might offer access to commonplaces and a good place to see how they are used.

But whichever source types you use, you should know that any well-researched paper will be supported by a balance of items from many different media, viewpoints, and levels of expertise.

Candela Citations

- Organizing Your Research Plan, modified. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/writing/textbooks/boundless-writing-textbook/the-research-process-2/organizing-your-research-plan-262/organizing-your-research-plan-51-1304/. Project: Boundless Writing. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Research steps. Provided by: Jean and Alexander Heard Library. Located at: http://researchguides.library.vanderbilt.edu/c.php?g=293170&p=1952201. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Thesis statement information, Pot of Gold, Information Literacy Tutorial. Provided by: Notre Dame. Located at: http://library.nd.edu/instruction/potofgold/investigating/?page=10. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Steps 2-4 in the Research Process come from Chapter 1: Writing and Research in the Academic Sphere and Chapter 2: Research Proposals and Thesis Statements. Authored by: Denise Snee, Kristin Houlton, and Nancy Heckel. Edited by Kimberly Jacobs.. Project: Research, Analysis, and Writing. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Research question example. Provided by: Duke University Libraries. Located at: http://guides.library.duke.edu/c.php?g=289688&p=1930772. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The Research Process graphic. Authored by: Kim Louie for Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Choosing and Developing Topics. Authored by: Jay Jordan. Provided by: University of Utah, University Writing Program. Project: Open2010. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of overwhelming menu options. Authored by: Ian Muttoo. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/7nrU1S. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike