An effective argument contains a thesis, supporting claims, and evidence to support those claims. The thesis is the writer’s central argument, or claim, and the supporting claims reinforce the validity of the thesis. When reading another writer’s argument, it is important to be able to distinguish between main points and sub-claims; being able to recognize the difference between the two will prove incredibly useful when composing your own thesis-driven essays.

As you may know, a writer’s thesis articulates the direction he or she will take with his or her argument. For example, let’s say that my thesis is as follows: “smoking should be banned on campus because of its health and environmental repercussions.” At least two things are clear from this statement: my central claim is that smoking should be banned on campus, and I will move from discussing the health impact of allowing smoking on campus to covering the environmental impact of allowing smoking on campus. These latter two ideas (the health and the environmental repercussions of allowing smoking on campus) are the author’s main points, which function as support for the author’s central claim (thesis), and they will likely comprise one or more body paragraphs of the writer’s thesis-driven essay.

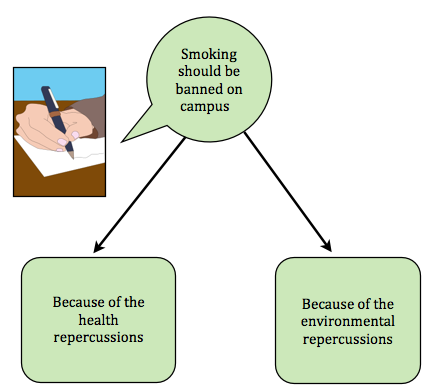

Let’s take a look at the following diagram:

This diagram translates into the following organizational plan:

- I argue that smoking should be banned on campus.

- Smoking should be banned on campus because of the health repercussions.

- Smoking should be banned on campus because of the environmental repercussions.

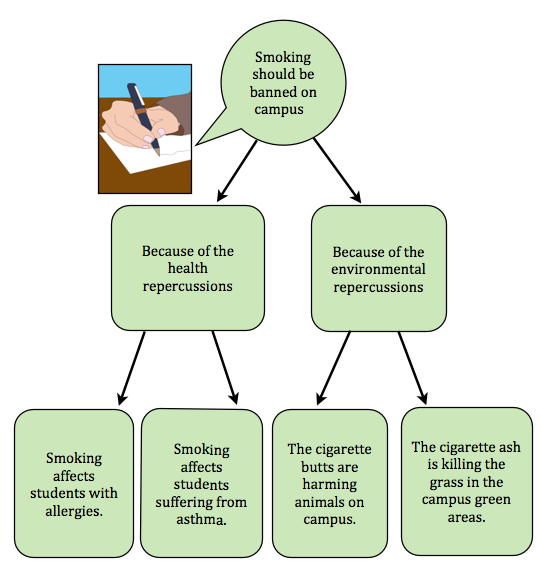

Points (A) and (B) will be explored in body paragraphs, will likely form the topic sentences of those body paragraphs, and will be supported by more claims specific to each point, or sub-claims. Let’s return to the previous diagram and see what happens when we include sub-claims:

This diagram translates into the following organizational plan:

- I argue that smoking should be banned on campus.

- Smoking should be banned on campus because of the health repercussions.

- Smoking affects students with allergies.

- Smoking affects students suffering from asthma.

- Smoking should be banned on campus because of the environmental repercussions.

- The cigarette butts are harming animals on campus.

- The cigarette ash is killing the grass in the campus green areas.

- Smoking should be banned on campus because of the health repercussions.

Assertions (1) and (2) listed under each main point are the writer’s sub-claims, statements that reinforce the validity of his or her main points. Think about it this way: every time a writer presents a claim, the reader likely asks, “What support do you have for that claim?” So, when the writer argues, “Smoking should be banned on campus,” the reader asks, “What support do you have for that claim?” And the writer responds with, “Because I’ve found that there are health and environmental repercussions.” Then, when the reader asks, “What support do you have for your claim that there are health and environmental repercussions to smoking on campus?” the writer can say, “Well, smoking negatively affects students suffering from asthma as well as those who have allergies, and the pollution caused by cigarettes is harming animals and killing the grass.” Each major claim bolsters the writer’s thesis, and each sub-claim bolsters one of the writer’s major claims; additionally, the claims get increasingly specific as they move from main points to sub-claims.

Then, the writer includes evidence to support each sub-claim. For instance, if I assert that “smoking affects students with allergies,” the reader would ask, “What support do you have for that claim?” And the writer might cite a poll taken on campus proving that students with allergies have suffered more when walking through smoky areas. To support the sub-claim that “smoking affects students suffering from asthma,” the writer might cite a report released by Student Health Services connecting the increase of on-campus asthma attacks to on-campus smoking. Those studies function as evidence to support two of the author’s sub-claims. Other evidence would be necessary to prove the validity of the writer’s other sub-claims.

Whenever you, as a reader, come across an assertion in a thesis-driven text, ask yourself, “What support is the writer offering to back this claim?” You can then chart the points made by the writer by filling in the answers you locate when reading the text. If a point is missing, take note of that, because the point’s absence might very well undermine the author’s argument. Similarly, as a writer, whenever you make an assertion, ask yourself, “What support can I offer to back this claim?” Then bolster your argument by adding supporting claims and evidence as needed.

Candela Citations

- Distinguishing Between Main Points and Sub-Claims. Authored by: Jennifer Janechek. Provided by: Writing Commons. Located at: https://writingcommons.org/distinguishing-between-main-points-and-sub-claims. License: CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives