Learning Objectives

- Exponential Equations with Unlike Bases

- Identify an exponential equation whose terms all have the same base

- Idenitfy cases where equations can be rewritten so all terms have the same base

- Apply the one-to-one property of exponents to solve an exponential equation

- Exponential Equations with Unlike Bases

- Use logarithms to solve exponential equations whose terms cannot be rewritten with the same base

- Solve exponential equations of the form [latex]y=A{e}^{kt}[/latex] for t

- Recognize when there may be extraneous solutions, or no solutions for exponential equations

- Logarithmic Equations

- Use the definition of a logarithm to solve logarithmic equations

- Use a graph to verify or analyze the solution to a logarithmic equation

- Applied Exponential and Logarithmic Equations

- Solve half-life problems

- Solve pH problems

- Solve problems involving Richter scale readings

- Solve problems involving decibels

Wild rabbits in Australia. The rabbit population grew so quickly in Australia that the event became known as the “rabbit plague.” (credit: Richard Taylor, Flickr)

In 1859, an Australian landowner named Thomas Austin released 24 rabbits into the wild for hunting. Because Australia had few predators and ample food, the rabbit population exploded. In fewer than ten years, the rabbit population numbered in the millions.

Uncontrolled population growth, as in the wild rabbits in Australia, can be modeled with exponential functions. Equations resulting from those exponential functions can be solved to analyze and make predictions about exponential growth. In this section, we will learn techniques for solving exponential functions.

When an exponential equation has the same base on each side, the exponents must be equal. This also applies when the exponents are algebraic expressions. Therefore, we can solve many exponential equations by using the rules of exponents to rewrite each side as a power with the same base. Then, we can set the exponents equal to one another, and solve for the unknown.

For example, consider the equation [latex]{3}^{4x - 7}=\frac{{3}^{2x}}{3}[/latex]. To solve for x, we use the division property of exponents to rewrite the right side so that both sides have the common base, 3. Then we apply the one-to-one property of exponents by setting the exponents equal to one another and solving for x:

In our first example, we solve an exponential equation whose terms all have a common base.

Example

Solve [latex]{2}^{x - 1}={2}^{2x - 4}[/latex].

In general, we can summarize solving exponential equations whose terms all have the same base in this way:

For any algebraic expressions S and T, and any positive real number [latex]b\ne 1[/latex]

- Use the rules of exponents to simplify, if necessary, so that the resulting equation has the form [latex]{b}^{S}={b}^{T}[/latex].

- Use the one-to-one property to set the exponents equal.

- Solve the resulting equation, S = T, for the unknown.

Rewriting Equations So All Powers Have the Same Base

Sometimes we can rewrite the terms in an equation as powers with a common base, and solve using the one-to-one property. This takes a keen eye for recognizing common powers. For example, you can rewrite 8 as [latex]2^3[/latex] or 36 as [latex]6^2[/latex] or [latex]\frac{1}{4}[/latex] as [latex]\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)^{2}[/latex]

Consider the equation [latex]256={4}^{x - 5}[/latex]. We can rewrite both sides of this equation as a power of 2. Then we apply the rules of exponents, along with the one-to-one property, to solve for x:

Example

Solve [latex]{8}^{x+2}={16}^{x+1}[/latex].

In our next example, we are given an exponential equation that contains a square root. Remember that you can write roots as rational exponents, so you may be able to find like bases when it is not completely obvious at first.

Example

Solve [latex]{2}^{5x}=\sqrt{2}[/latex].

By changing [latex]\sqrt{2}[/latex] to [latex]{2}^{\frac{1}{2}}[/latex] we were able to solve the equation in the previous example. In general, here are some steps to consider when you are solving exponential equations. A good first step is always to determine whether you can rewrite the terms with a common base.

- Rewrite each side in the equation as a power with a common base.

- Use the rules of exponents to simplify, if necessary, so that the resulting equation has the form [latex]{b}^{S}={b}^{T}[/latex].

- Use the one-to-one property to set the exponents equal.

- Solve the resulting equation, S = T, for the unknown.

Think About It

Do all exponential equations have a solution? If not, how can we tell if there is a solution during the problem-solving process? Write your thoughts in the textbox below before you check our proposed answer.

In the next example we show you a case where there is no solution to an exponential equation. Remember how exponential functions are defined and ask yourself – “does this make sense” before diving into solving exponential equations.

Example

Solve [latex]{3}^{x+1}=-2[/latex].

Analysis of the Solution

Exponential Equations with unlike Bases

Sometimes the terms of an exponential equation cannot be rewritten with a common base. In these cases, we solve by taking the logarithm of each side. Recall, since [latex]\mathrm{log}\left(a\right)=\mathrm{log}\left(b\right)[/latex] is equivalent to a = b, we may apply logarithms with the same base on both sides of an exponential equation.

In our first example we will use the law of logs combined with factoring to solve an exponential equation whose terms do not have the same base. Note how first, we rewrite the exponential terms as logarithms.

Example

Solve [latex]{5}^{x+2}={4}^{x}[/latex].

In general we can solve exponential equations whose terms do not have like bases in the following way:

- Apply the logarithm of both sides of the equation.

- If one of the terms in the equation has base 10, use the common logarithm.

- If none of the terms in the equation has base 10, use the natural logarithm.

- Use the rules of logarithms to solve for the unknown.

Think About It

Is there any way to solve [latex]{2}^{x}={3}^{x}[/latex]?

Use the textbox below to formulate an answer or example before you look at the solution.

Equations Containing [latex]e[/latex]

Example

Solve [latex]100=20{e}^{2t}[/latex].

Analysis of the Solution

Using laws of logs, we can also write this answer in the form [latex]t=\mathrm{ln}\sqrt{5}[/latex]. If we want a decimal approximation of the answer, we use a calculator.

Think About It

Does every equation of the form [latex]y=A{e}^{kt}[/latex] have a solution? Write your thoughts or an example in the textbox below before you check the answer.

We will provide one more example using the continuous growth formula, but this time we have to do a couple steps of algebra to get in it a form that can be solved.

Example

Solve [latex]4{e}^{2x}+5=12[/latex].

Extraneous Solutions

Sometimes the methods used to solve an equation introduce an extraneous solution, which is a solution that is correct algebraically but does not satisfy the conditions of the original equation. One such situation arises in solving when the logarithm is taken on both sides of the equation. In such cases, remember that the argument of the logarithm must be positive. If the number we are evaluating in a logarithm function is negative, there is no output.

In the next example we will solve an exponential equation that is quadratic in form. We will factor first and then use the zero product principle. Note how we find two solutions, but reject one that does not satisfy the original equaiton.

Example

Solve [latex]{e}^{2x}-{e}^{x}=56[/latex].

Analysis of the Solution

When we plan to use factoring to solve a problem, we always get zero on one side of the equation, because zero has the unique property that when a product is zero, one or both of the factors must be zero. We reject the equation [latex]{e}^{x}=-7[/latex] because a positive number never equals a negative number. The solution [latex]x=\mathrm{ln}\left(-7\right)[/latex] is not a real number, and in the real number system this solution is rejected as an extraneous solution.

Think About It

Does every logarithmic equation have a solution? Write your ideas, or a counter example in the box below.

Logarithmic Equations

We have already seen that every logarithmic equation [latex]{\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)=y[/latex] is equivalent to the exponential equation [latex]{b}^{y}=x[/latex]. We can use this fact, along with the rules of logarithms, to solve logarithmic equations where the argument is an algebraic expression.

For example, consider the equation [latex]{\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(2\right)+{\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(3x - 5\right)=3[/latex]. To solve this equation, we can use rules of logarithms to rewrite the left side in compact form and then apply the definition of logs to solve for x:

Example

Solve [latex]2\mathrm{ln}x+3=7[/latex].

Analysis of the solution

The solution for the previous equation was [latex]x={e}^{2}[/latex], this is often referred to as the exact solution. Sometimes, you may be asked to give an approximation, which would be more useful to someone using the result for a financial, scientific or engineering application. The approximation for [latex]x={e}^{2}[/latex] can be found with a calculator. [latex]x={e}^{2}\approx{7.4}[/latex]

In general, we can describe using the definition of a logarithm to solve logarithmic equations as follows:

For any algebraic expression S and real numbers b and c, where [latex]b>0,\text{ }b\ne 1[/latex],

Example

Solve [latex]2\mathrm{ln}\left(6x\right)=7[/latex].

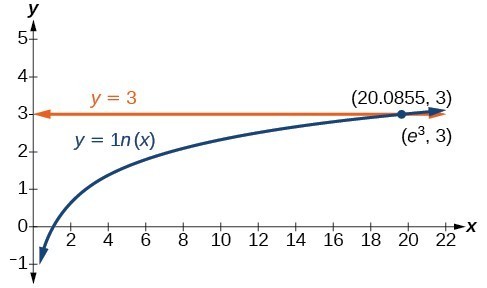

In our next example we will show you the power of using graphs to analyze solutions to logarithmic equations. By turning each side of the equation into a function and plotting them on the same set of axes, we can see how they interact with each other. In this case, we get a logarithmic function and a horizontal line, and find that the solution is the point where the two intersect.

Example

Solve [latex]\mathrm{ln}x=3[/latex].

In the same way that a story can help you understand a complex concept, graphs can help us understand a wide variety of concepts in mathematics. Visual representations of the parts of an equation can be created by turning each side into a function and plotting the functions on the same set of axes.

Use the one-to-one property of logarithms to solve logarithmic equations

As with exponential equations, we can use the one-to-one property to solve logarithmic equations. The one-to-one property of logarithmic functions tells us that, for any real numbers x > 0, S > 0, T > 0 and any positive real number b, where [latex]b\ne 1[/latex],

For example,

So, if [latex]x - 1=8[/latex], then we can solve for x, and we get x = 9. To check, we can substitute x = 9 into the original equation: [latex]{\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(9 - 1\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(8\right)=3[/latex]. In other words, when a logarithmic equation has the same base on each side, the arguments must be equal. This also applies when the arguments are algebraic expressions. Therefore, when given an equation with logs of the same base on each side, we can use rules of logarithms to rewrite each side as a single logarithm. Then we use the fact that logarithmic functions are one-to-one to set the arguments equal to one another and solve for the unknown.

Example

Solve [latex]\mathrm{log}\left(3x - 2\right)-\mathrm{log}\left(2\right)=\mathrm{log}\left(x+4\right)[/latex]

Check your results.

Note, when solving an equation involving logarithms, always check to see if the answer is correct or if there is an extraneous solution.

In general, we can summarize solving logarithmic equations as follows:

For [latex]{\mathrm{log}}_{b}S={\mathrm{log}}_{b}T\text{ if and only if }S=T[/latex]

- Use the rules of logarithms to combine like terms, if necessary, so that the resulting equation has the form [latex]{\mathrm{log}}_{b}S={\mathrm{log}}_{b}T[/latex].

- Use the one-to-one property to set the arguments equal.

- Solve the resulting equation, S = T, for the unknown.

Example

[latex]{\mathrm{log}}_{b}S={\mathrm{log}}_{b}T\text{ if and only if }S=T[/latex]

Analysis of the Solution

There are two solutions: x = 3 or x = –1. The solution x = –1 is negative, but it checks when substituted into the original equation because the argument of the logarithm functions is still positive.

Applications of Logarithmic Equations

In previous sections, we learned the properties and rules for both exponential and logarithmic functions. We have seen that any exponential function can be written as a logarithmic function and vice versa. We have used exponents to solve logarithmic equations and logarithms to solve exponential equations. We are now ready to combine our skills to solve equations that model real-world situations, whether the unknown is in an exponent or in the argument of a logarithm.

One such application is called half-life, which refers to the amount of time it takes for half a given quantity of radioactive material to decay. The table below lists the half-life for several of the more common radioactive substances.

| Substance | Use | Half-life |

|---|---|---|

| gallium-67 | nuclear medicine | 80 hours |

| cobalt-60 | manufacturing | 5.3 years |

| technetium-99m | nuclear medicine | 6 hours |

| americium-241 | construction | 432 years |

| carbon-14 | archeological dating | 5,715 years |

| uranium-235 | atomic power | 703,800,000 years |

We can see how widely the half-lives for these substances vary. Knowing the half-life of a substance allows us to calculate the amount remaining after a specified time. We can use the formula for radioactive decay:

where

- [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is the amount initially present

- T is the half-life of the substance

- t is the time period over which the substance is studied

- [latex]A(t)[/latex] is the amount of the substance present after time t

Example

How long will it take for ten percent of a 1000-gram sample of uranium-235 to decay?

Analysis of the Solution

Ten percent of 1000 grams is 100 grams. If 100 grams decay, the amount of uranium-235 remaining is 900 grams.

pH

In chemistry, pH is used as a measure of the acidity or alkalinity of a substance. The pH scale runs from 0 to 14. Substances with a pH less than 7 are considered acidic, and substances with a pH greater than 7 are said to be alkaline. In our next example we will find how doubling the concentration of hydrogen ions in a liquid affects pH.

Example

In chemistry, [latex]\text{pH}=-\mathrm{log}\left[{H}^{+}\right][/latex]. If the concentration of hydrogen ions in a liquid is doubled, what is the effect on pH?

Richter Scale

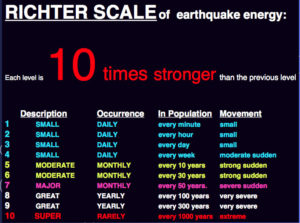

Richter Scale of Earthquake Energy

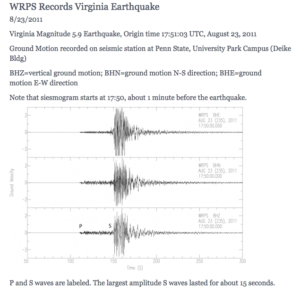

The Richter scale is a logarithmic function that is used to measure the magnitude of earthquakes. The magnitude of an earthquake is related to how much energy is released by the quake. Instruments called seismographs detect movement in the earth; the smallest movement that can be detected shows on a seismograph as a wave with amplitude [latex]A_{0}[/latex].

A – the measure of the amplitude of the earthquake wave

[latex]A_{0}[/latex] – the amplitude of the smallest detectable wave (or standard wave)

From this you can find R, the Richter scale measure of the magnitude of the earthquake using the formula:

[latex]R=\mathrm{log}\left(\frac{A}{A_{0}}\right)[/latex]

The intensity of an earthquake will typically measure between 2 and 10 on the Richter scale. Any earthquakes registering below a 5 are fairly minor; they may shake the ground a bit, but are seldom strong enough to cause much damage. Earthquakes with a Richter rating of between 5 and 7.9 are much more severe, and any quake above an 8 is likely to cause massive damage. (The highest rating ever recorded for an earthquake is 9.5 during the 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile.)

Example

An earthquake is measured with a wave amplitude 392 times as great as [latex]A_{0}[/latex]. What is the magnitude of this earthquake using the Richter scale, to the nearest tenth?

A difference of 1 point on the Richter scale equates to a 10-fold difference in the amplitude of the earthquake (which is related to the wave strength). This means that an earthquake that measures 3.6 on the Richter scale has 10 times the amplitude of one that measures 2.6.

In the Richter scale example, the wave amplitude of the earthquake was 392 times normal. What if it were 10 times that, or 3,920 times normal? To find the measurement of that size earthquake on the Richter scale, you find log 3920. A calculator gives a value of 3.5932…or 3.6, when rounded to the nearest tenth. One extra point on the Richter scale can mean a lot more shaking!

Decibels

Turn it Down

Sound is measured in a logarithmic scale using a unit called a decibel. The formula looks similar to the Richter scale:

[latex]d=10\mathrm{log}\left(\frac{P}{P_{0}}\right)[/latex]

where P is the power or intensity of the sound and P0 is the weakest sound that the human ear can hear. In the next example we will find how much more intense the noise from a dishwasher is than the noise from a hot water pump.

Example

One hot water pump has a noise rating of 50 decibels. One dishwasher, however, has a noise rating of 62 decibels. The dishwasher noise is how many times more intense than the hot water pump noise?

Applications of logarithms and exponentials are everywhere in science. We hope the examples here have given you an idea of how useful they can be.

Summary

We can use the one-to-one property of exponents to solve exponential equations whose bases are the same. The terms in some exponential equations can be rewritten with the same base, allowing us to use the same principle. There are exponential equations that do not have solutions because we define exponential functions as having a positive base. When restrictions are placed on the inputs of a function, it is natural that there will be restrictions on the output as well.

The inverse operation of exponentiation is the logarithm, so we can use logarithms to solve exponential equations whose terms do not have the same bases. This is similar to using multiplication to “undo” division or addition to “undo” subtraction. It is important to check exponential equations for extraneous solutions or no solutions.

Put it Together

Ground Motion recorded on seismic station at Penn State, University Park Campus (Deike Bldg)

In the beginning of this module we left Joan with a plan to try and stump her grandfather, the geologist, with the following math problem.

The Alaska quake of 1964 had a Richter scale value of 8.5, how many times greater than baseline was the measured wave amplitude recorded by a seismograph?

[latex]8.5=\mathrm{log}\left(\frac{A}{A_{0}}\right)[/latex]

He was so excited to have found something he and Joan could talk about, he beamed when he saw that she had a problem for him to solve.

“I probably knew how to solve that once, but it has been a long time,” said Grandpa. “Will you show me?”

First, Joan explained to her grandpa that the goal of the problem was to get the argument out of the logarithm. She remembered that a logarithm is an exponent, so her first step was to rewrite the logarithm as an exponential:

[latex]\begin{array}{c}8.5=\mathrm{log}\left(\frac{A}{A_{0}}\right)\\{10}^{8.5}=\frac{A}{A_{0}}\\{10}^{8.5}\cdot{A_{0}}={A}\end{array}[/latex]

Joan entered [latex]{10}^{8.5}[/latex] into a calculator and got the following number:

[latex]316,227,766.017[/latex]

Wow, the amplitude of the waves that caused the Alaska earthquake of 1964 was 3 million times greater than the baseline reading!

When working with values that are very large or very small, it is very helpful to work in logarithmic or exponential scales. It helps scientists avoid having to do calculations with massive numbers. Additionally, it makes comparisons between different measurements easier to understand.

Joan had such a good time explaining to Grandpa how the math problem worked, she forgot all about having stumped him. Later that night, Hobbes didn’t wake her up as he let himself out of the window and down the ladder Anne and Joan made for him. And Joan was happily saving away for the graduation trip that she was planning to take with Hazel (and maybe even her next dreamy boyfriend). Algebra kept Joan from driving while intoxicated, taught her how food poisoning worked, and even helped her choose a good cell phone plan. But this isn’t what Joan will remember now that she’s finished her math class. What she’ll remember is that she now has the power and knowledge to figure out solutions to so many of the challenges in her real life. And we hope you remember that, too! (Don’t worry; if you forget some of the math rules along the way, you can always check back and refresh your memory. We’ll be waiting.)

The figure below shows the graphs of the two separate expressions in the equation [latex]{3}^{x+1}=-2[/latex] as [latex]y={3}^{x+1}[/latex] and [latex]y=-2[/latex]. The two graphs do not cross showing us that the left side is never equal to the right side. Thus the equation has no solution.