The Achaemenid Empire

Under Cyrus the Great and Darius the Great, the Achaemenid Empire became the first global empire.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the Achaemenid as the first global empire

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Around 550 BCE, Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) conquered the Median

Empire and started the expansion of the Achaemenid Empire, assimilating the neighboring Lydian and Neo-Babylonian empires. - Cyrus the Great was succeeded by his son Cambryses II in 530 BCE and then the usurper Gaumata, and finally by Darius the Great in 522 BCE.

- By the time of Darius the Great and his son, Xerxes, the Achaemenid Empire had expanded to include Mesopotamia,

Egypt, Anatolia, the Southern Caucasus, Macedonia, the western Indus basin, as well as parts of Central Asia, northern Arabia and northern Libya. - At its height around 475 BCE, the Achaemenid Empire ruled over 44% of the world’s population, the highest figure for any empire in history.

Key Terms

- Cyrus the Great: Cyrus II of Persia, also known as Cyrus the Great, created the largest empire the world had seen.

- Darius the Great: The third king of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, who ruled at its peak from c. 522-486 BCE.

- Median Empire: One of the four major powers of the ancient Near East (with Babylonia, Lydia, and Egypt), until it was conquered by Cyrus the Great in 550 BCE.

- Pasargadae: The capital of the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great.

The Achaemenid Empire, c. 550-330 BCE, or First Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great, in Western and Central Asia. The dynasty drew its name from Achaemenes, who, from 705-675 BCE, ruled Persis, which was land bounded on the west by the Tigris River and on the south by the Persian Gulf. It was the first centralized nation-state, and during expansion in approximately 550-500 BCE, it became the first global empire and eventually ruled over significant portions of the ancient world.

Empire Beginnings

By the 7th century BCE, a group of ancient Iranian people had established the Median Empire, a vassal state under the Assyrian Empire that later tried to gain its independence in the 8th century BCE. After Assyria fell in 605 BCE, Cyaxares, king of the Medes, extended his rule west across Iran.

Around 550 BCE, Cyrus II of Persia, who became known as Cyrus the Great, rose in rebellion against the Median Empire, eventually conquering the Medes to create the first Persian Empire, also known as the Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus utilized his tactical genius, as well as his understanding of the socio-political conditions governing his territories, to eventually assimilate the neighboring Lydian and Neo-Babylonian empires into the new Persian Empire.

Relief of Cyrus the Great: Cyrus II of Persia, better known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Under his rule, the empire assimilated all the civilized states of the ancient Near East, and eventually conquered most of Southwest Asia and much of Central Asia and the Caucasus.

Achaemenid Expansion

The empire was ruled by a series of monarchs who joined its disparate tribes by constructing a complex network of roads. The unified form of the empire came in the form of a central administration around the city of Pasargadae, which was erected by Cyrus c. 550 BCE. After his death in 530 BCE, Cyrus was succeeded by his son Cambyses II, who conquered Egypt, Nubia, and Cyrenaica in 525 BCE; he died in 522 BCE during a revolt.

During the king’s long absence during his expansion campaign, a Zoarastrian priest, named Guamata, staged a coup by impersonating Cambryses II’s younger brother, Bardiya, and seized the throne. Yet in 522 BCE, Darius I, also known as Darius the Great, overthrew Gaumata and solidified control of the territories of the Achaemenid Empire, beginning what would be a historic consolidation of lands.

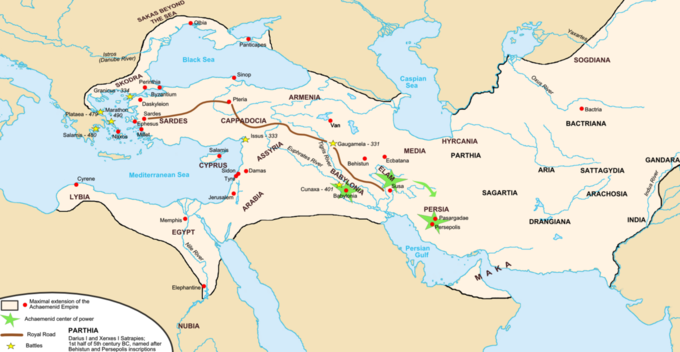

Achaemenid Empire in the time of Darius and Xerxes: At its height, the Achaemenid Empire ruled over 44% of the world’s population, the highest figure for any empire in history.

Between c. 500-400 BCE, Darius the Great and his son, Xerxe I, ruled the Persian Plateau and all of the territories formerly held by the Assyrian Empire, including Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Cyprus. It eventually came to control Egypt, as well. This expansion continued even further afield with Anatolia and the Armenian Plateau, much of the Southern Caucasus, Macedonia, parts of Greece and Thrace, Central Asia as far as the Aral Sea, the Oxus and Jaxartes areas, the Hindu Kush and the western Indus basin, and parts of northern Arabia and northern Libya.

This unprecedented area of control under a single ruler stretched from the Indus Valley in the east to Thrace and Macedon on the northeastern border of Greece. At its height, the Achaemenid Empire ruled over 44% of the world’s population, the highest such figure for any empire in history.

Government and Trade in the Achaemenid Empire

Emperors Cyrus II and Darius I created a centralized government and extensive trade network in the Achaemenid Empire.

Learning Objectives

Discuss how the central government provided cultural and economic reform

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Cyrus the Great maintained control over a vast empire by installing regional governors, called satraps, to rule individual provinces.

- When Darius the Great ascended the throne in 522 BCE, he organized a new uniform monetary system and

established Aramaic as the official language of the empire. - Trade infrastructure facilitated the exchange of commodities in the far reaches of the empire, including the Royal Road, standardized language, and a postal service.

- Tariffs on trade from the territories were one of the empire’s main sources of revenue, in addition to agriculture and tribute.

Key Terms

- Cyrus Cylinder: An ancient clay artifact that has been called the oldest-known charter of human rights.

- Behistun

Inscription: An inscription carved in a cliff face of Mount Behistrun in Iran; it provided a key to deciphering cuneiform script. - satrapy: The territory under the rule of a satrap.

- satrap: The governor of a province in the ancient Median and Achaemenid (Persian) Empires.

The Achaemenid Empire reached enormous size under the leadership of Cyrus II of Persia (576-530 BCE), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, who created a multi-state empire. Called Cyrus the Elder by the Greeks, he founded an empire initially comprising all the previous civilized states of the ancient Near East and eventually most of Southwest and Central Asia and the Caucus region, stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indus River. Control of this large territory involved a centralized government, territorial monarchs who served as proxy rulers for the emperor, and an extensive system of commerce and trade.

Government Organization

Cyrus, whose rule lasted between 29 and 31 years, until his death in battle in 530 BCE, controlled the vast Achaemenid Empire through the use of regional monarchs, called satrap, who each oversaw a territory called a satrapy. The basic rule of governance was based upon the loyalty and obedience of the satrapy to the central power, the king, and compliance with tax laws. Cyrus also connected the various regions of the empire through an innovative postal system that made use of an extensive roadway and relay stations.

Cyrus the Great was recognized for achievements in human rights and politics, having influenced both Eastern and Western Civilization. The ancient Babylonians called him “The Liberator,” while the modern nation of Iran calls Cyrus its “father.”

Cyrus Cylinder

The Cyrus Cylinder is an ancient clay artifact, now broken into several fragments, that has been called the oldest-known charter of universal human rights and a symbol of his humanitarian rule.

The cylinder dates from the 6th century BCE, and was discovered in the ruins of Babylon in Mesopotamia, now Iraq, in 1879. In addition to describing the genealogy of Cyrus, the declaration in Akkadian cuneiform script on the cylinder is considered by many Biblical scholars to be evidence of Cyrus’s policy of repatriation of the Jewish people following their captivity in Babylon.

The historical nature of the cylinder has been debated, with some scholars arguing that Cyrus did not make a specific decree, but rather that the cylinder articulated his general policy allowing exiles to return to their homelands and rebuild their temples.

In fact, the policies of Cyrus with respect to treatment of minority religions were well documented in Babylonian texts, as well as in Jewish sources. Cyrus was known to have an overall attitude of religious tolerance throughout the empire, although it has been debated whether this was by his own implementation or a continuation of Babylonian and Assyrian policies.

Darius Improvements

When Darius I (550-486 BCE), also known as Darius the Great, ascended the throne of the Achaemenid Empire in 522 BCE, he established Aramaic as the official language and devised a codification of laws for Egypt. Darius also sponsored work on construction projects throughout the empire, focusing on improvement of the cities of Susa, Pasargadae, Persepolis, Babylon, and various municipalities in Egypt.

When Darius moved his capital from Pasargadae to Persepolis, he revolutionized the economy by placing it on a silver and gold coinage and introducing a regulated and sustainable tax system. This structure precisely tailored the taxes of each satrapy based on its projected productivity and economic potential. For example, Babylon was assessed for the highest amount of silver taxes, while Egypt owed grain in addition to silver taxes.

Persian reliefs in the city of Persepolis: Darius the Great moved the capital of the Achaemenid Empire to Persepolis c. 522 BCE. He initiated several major architectural projects, including the construction of a palace and a treasure house.

Behistun Inscription

Sometime after his coronation, Darius ordered an inscription to be carved on a limestone cliff of Mount Behistun in modern Iran. The Behistun Inscription, the text of which Darius wrote, came to have great linguistic significance as a crucial clue in deciphering cuneiform script.

The inscription begins by tracing the ancestry of Darius, followed by a description of a sequence of events following the deaths of the previous two Achaemenid emperors, Cyrus the Great and Cyrus’s son, Cambyses II, in which Darius fought 19 battles in one year to put down numerous rebellions throughout the Persian lands.

The inscription, which is approximately 15 meters high and 25 meters wide, includes three versions of the text in three different cuneiform languages: Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian, which was a version of Akkadian. Researchers were able to compare the scripts and use it to help decipher ancient languages, in this way making the Behistun Inscription as valuable to cuneiform as the Rosetta Stone is to Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Behistun Inscription: A section of the Behistun Inscription on a limestone cliff of Mount Behistun in western Iran, which became a key in deciphering cuneiform script.

Commerce and Trade

Under the Achaemenids, trade was extensive and there was an efficient infrastructure that facilitated the exchange of commodities in the far reaches of the empire. Tariffs on trade were one of the empire’s main sources of revenue, in addition to agriculture and tribute.

The satrapies were linked by a 2,500-kilometer highway, the most impressive stretch of which was the Royal Road, from Susa to Sardis. The relays of mounted couriers could reach the most remote areas in 15 days. Despite the relative local independence afforded by the satrapy system, royal inspectors regularly toured the empire and reported on local conditions using this route.

Achaemenid golden bowl with lion imagery: Trade in the Achaemenid Empire was extensive. Infrastructure, including the Royal Road, standardized language, and a postal service facilitated the exchange of commodities in the far reaches of the empire.

Military

Cyrus the Great created an organized army to enforce national authority, despite the ethno-cultural diversity among the subject nations, the empire’s enormous geographic size, and the constant struggle for power by regional competitors.

This professional army included the Immortals unit, comprising 10,000 highly trained heavy infantry. Under Darius the Great, Persia would become the first empire to inaugurate and deploy an imperial navy, with personnel that included Phoenicians, Egyptians, Cypriots, and Greeks.

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism, an ancient Persian religion, had a major influence on the culture and religion of all other monotheistic religions in the region.

Learning Objectives

Explain Zoroastrianism and its impact on Persian culture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of Zoroaster, an Iranian prophet, who worshiped Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord), as its Supreme Being.

- Leading characteristics, such as messianism, heaven and hell, and free will are said to have influenced other religious systems, including Second Temple Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity, and Islam.

- Zoroastrianism served as the state religion of the pre-Islamic Iranian empires from c. 600 BCE to 650 CE, but saw a steep decline after the Muslim conquest of Persia.

- The religion states that active participation in life through good deeds is necessary to ensure happiness and to keep chaos at bay.

Key Terms

- Sassanids: The last Iranian empire before the rise of Islam.

- Gnosticism: A modern term categorizing a collection of ancient religions whose adherents shunned the material world—

which they viewed as created by the demiurge—and embraced the spiritual world. - messianism: The belief in a messiah, who acts as a savior, redeemer or liberator of a group of people.

- eschatological: A part of theology concerned with the final events of history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity, often referred to as the “end times.”

Overview and Theology

Zoroastrianism is one of the world’s oldest religions. It ascribed to the teachings of the Iranian prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra), and exalted their deity of wisdom, Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord), as its Supreme Being. Leading characteristics, such as messianism, heaven and hell, and free will are said to have influenced other religious systems, including Second Temple Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity, and Islam. With possible roots dating back to the second millennium BCE, Zoroastrianism enters recorded history in the 5th-century BCE. It served as the state religion of the pre-Islamic Iranian empires from around 600 BCE to 650 CE. Zoroastrianism was suppressed from the 7th century onwards, following the Muslim conquest of Persia. Recent estimates place the current number of Zoroastrians at around 2.6 million, with most living in India and Iran.

The most important texts of the religion are those of the Avesta, which includes the writings of Zoroaster, known as the Gathas and the Yasna. The Gathas are enigmatic poems that define the religion’s precepts, while the Yasna is the scripture. The full name by which Zoroaster addressed the deity is: Ahura, The Lord Creator, and Mazda, Supremely Wise. He proclaimed that there is only one God, the singularly creative and sustaining force of the Universe. He also stated that human beings are given a right of choice, and because of cause and effect are also responsible for the consequences of their choices. The contesting force to Ahura Mazda was called Angra Mainyu, or angry spirit. Post-Zoroastrian scripture introduced the concept of Ahriman, the Devil, which was effectively a personification of Angra Mainyu.

In Zoroastrianism, water (apo, aban) and fire (atar, azar) are agents of ritual purity, and the associated purification ceremonies are considered the basis of ritual life. In Zoroastrian cosmogony, water and fire are respectively the second and last primordial elements to have been created, and scripture considers fire to have its origin in the waters. Both water and fire are considered life-sustaining, and both water and fire are represented within the precinct of a fire temple. Zoroastrians usually pray in the presence of some form of fire (which can be considered evident in any source of light), and the culminating rite of the principle act of worship constitutes a “strengthening of the waters.” Fire is considered a medium through which spiritual insight and wisdom is gained, and water is considered the source of that wisdom.

The religion states that active participation in life through good deeds is necessary to ensure happiness and to keep chaos at bay. This active participation is a central element in Zoroaster’s concept of free will, and Zoroastrianism rejects all forms of monasticism. Ahura Mazda will ultimately prevail over the evil Angra Mainyu or Ahriman, at which point the universe will undergo a cosmic renovation and time will end. In the final renovation, all of creation—even the souls of the dead that were initially banished to “darkness”—will be reunited in Ahura Mazda, returning to life in the undead form. At the end of time, a savior-figure (a Saoshyant) will bring about a final renovation of the world (frashokereti), in which the dead will be revived.

Zoroastrian Priest: Painted clay and alabaster head of a Zoroastrian priest wearing a distinctive Bactrian-style headdress, Takhti-Sangin, Tajikistan, Greco-Bactrian kingdom, 3rd-2nd century BCE.

History

The roots of Zoroastrianism are thought to have emerged from a common prehistoric Indo-Iranian religious system dating back to the early 2nd millennium BCE. The prophet Zoroaster himself, though traditionally dated to the 6th century BCE, is thought by many modern historians to have been a reformer of the polytheistic Iranian religion who lived in the 10th century BCE. Zoroastrianism as a religion was not firmly established until several centuries later. Zoroastrianism enters recorded history in the mid-5th century BCE. Herodotus’ The Histories (completed c. 440 BCE) includes a description of Greater Iranian society with what may be recognizably Zoroastrian features, including exposure of the dead.

The Histories is a primary source of information on the early period of the Achaemenid era (648-330 BCE), in particular with respect to the role of the Magi. According to Herodotus i.101, the Magi were the sixth tribe of the Medians (until the unification of the Persian empire under Cyrus the Great, all Iranians were referred to as “Mede” or “Mada” by the peoples of the Ancient World). The Magi appear to have been the priestly caste of the Mesopotamian-influenced branch of Zoroastrianism today known as Zurvanism, and they wielded considerable influence at the courts of the Median emperors.

Darius I, and later Achaemenid emperors, acknowledged their devotion to Ahura Mazda in inscriptions (as attested to several times in the Behistun inscription), and appear to have continued the model of coexistence with other religions. Whether Darius was a follower of Zoroaster has not been conclusively established, since devotion to Ahura Mazda was (at the time) not necessarily an indication of an adherence to Zoroaster’s teaching. A number of the Zoroastrian texts that today are part of the greater compendium of the Avesta have been attributed to that period.

The religion would be professed many centuries following the demise of the Achaemenids in mainland Persia and the core regions of the former Achaemenid Empire—

most notably Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus. In the Cappadocian kingdom (whose territory was formerly an Achaemenid possession), Persian colonists who were cut off from their co-religionists in Iran proper continued to practice the Zoroastrianism of their forefathers. There, Strabo, observing in the first century BCE, records that these “fire kindlers” possessed many “holy places of the Persian Gods,” as well as fire temples. Strabo furthermore relates, that they were “noteworthy enclosures; and in their midst there is an altar, on which there is a large quantity of ashes and where the magi keep the fire ever burning.” Throughout, and after, the Hellenistic periods in the aforementioned regions, the religion would be strongly revived.

As late as the Parthian period, a form of Zoroastrianism was without a doubt the dominant religion in the Armenian lands. The Sassanids aggressively promoted the Zurvanite form of Zoroastrianism, often building fire temples in captured territories to promote the religion. During the period of their centuries long suzerainty over the Caucasus, the Sassanids made attempts to promote Zoroastrianism there with considerable successes. It was also prominent in the pre-Christian Caucasus (especially modern-day Azerbaijan).

Candela Citations

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Achaemenid Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaemenid_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cyrus the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_the_Great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Xerxes I. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xerxes_I. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Darius the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darius_I. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pasargadae. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pasargadae. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Map achaemenid empire en. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_achaemenid_empire_en.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cyrus II of Persia. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Olympic_Park_Cyrus-3.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cyrus Cylinder. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_Cylinder. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Behistun Inscription. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behistun_Inscription. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Royal Road. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Road. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Aramaic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aramaic_language. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Babylon. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylon. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Achaemenid Empire. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaemenid_Empire. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Darius the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darius_the_great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cyrus the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_the_great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Map achaemenid empire en. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_achaemenid_empire_en.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cyrus II of Persia. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Olympic_Park_Cyrus-3.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Behistun Inscription. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bisotun_Iran_Relief_Achamenid_Period.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Persepolis reliefs 2005a. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Persepolis_reliefs_2005a.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Gold cup kalardasht. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gold_cup_kalardasht.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Zoroastrianism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoroastrianism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Map achaemenid empire en. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_achaemenid_empire_en.png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cyrus II of Persia. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Olympic_Park_Cyrus-3.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Behistun Inscription. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bisotun_Iran_Relief_Achamenid_Period.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Persepolis reliefs 2005a. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Persepolis_reliefs_2005a.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Gold cup kalardasht. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gold_cup_kalardasht.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- BactrianZoroastrian.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoroastrianism#/media/File:BactrianZoroastrian.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright