Learning Objectives

- Name the major regions of the adult brain

- Describe the connections between the cerebrum and brain stem through the diencephalon, and from those regions into the spinal cord

- Recognize the complex connections within the subcortical structures of the basal nuclei

- Explain the arrangement of gray and white matter in the spinal cord

The brain and the spinal cord are the central nervous system, and they represent the main organs of the nervous system. The spinal cord is a single structure, whereas the adult brain is described in terms of four major regions: the cerebrum, the diencephalon, the brain stem, and the cerebellum. A person’s conscious experiences are based on neural activity in the brain. The regulation of homeostasis is governed by a specialized region in the brain. The coordination of reflexes depends on the integration of sensory and motor pathways in the spinal cord.

The Cerebrum

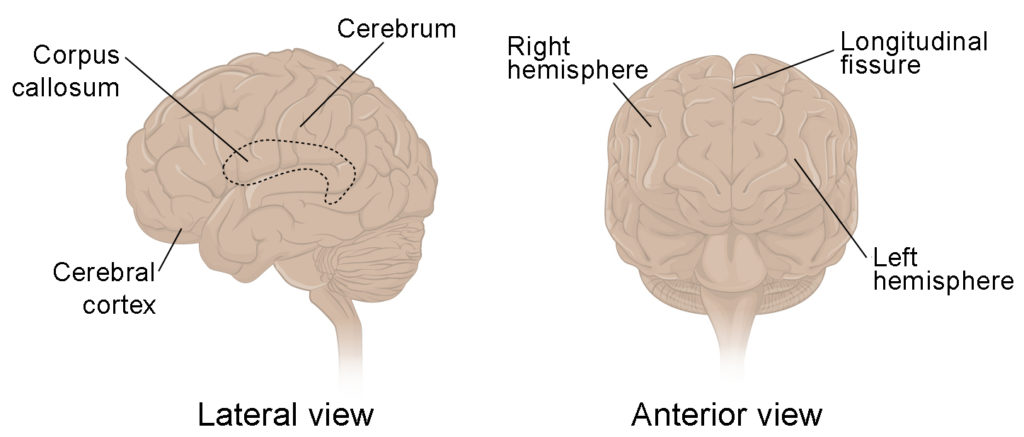

The iconic gray mantle of the human brain, which appears to make up most of the mass of the brain, is the cerebrum (Figure 1). The wrinkled portion is the cerebral cortex, and the rest of the structure is beneath that outer covering. There is a large separation between the two sides of the cerebrum called the longitudinal fissure. It separates the cerebrum into two distinct halves, a right and left cerebral hemisphere. Deep within the cerebrum, the white matter of the corpus callosum provides the major pathway for communication between the two hemispheres of the cerebral cortex.

Figure 1. This figure shows the lateral view on the left panel and anterior view on the right panel of the brain. The major parts including the cerebrum are labeled.

Many of the higher neurological functions, such as memory, emotion, and consciousness, are the result of cerebral function. The complexity of the cerebrum is different across vertebrate species. The cerebrum of the most primitive vertebrates is not much more than the connection for the sense of smell. In mammals, the cerebrum comprises the outer gray matter that is the cortex (from the Latin word meaning “bark of a tree”) and several deep nuclei that belong to three important functional groups. The basal nuclei are responsible for cognitive processing, the most important function being that associated with planning movements. The basal forebrain contains nuclei that are important in learning and memory. The limbic cortex is the region of the cerebral cortex that is part of the limbic system, a collection of structures involved in emotion, memory, and behavior.

Cerebral Cortex

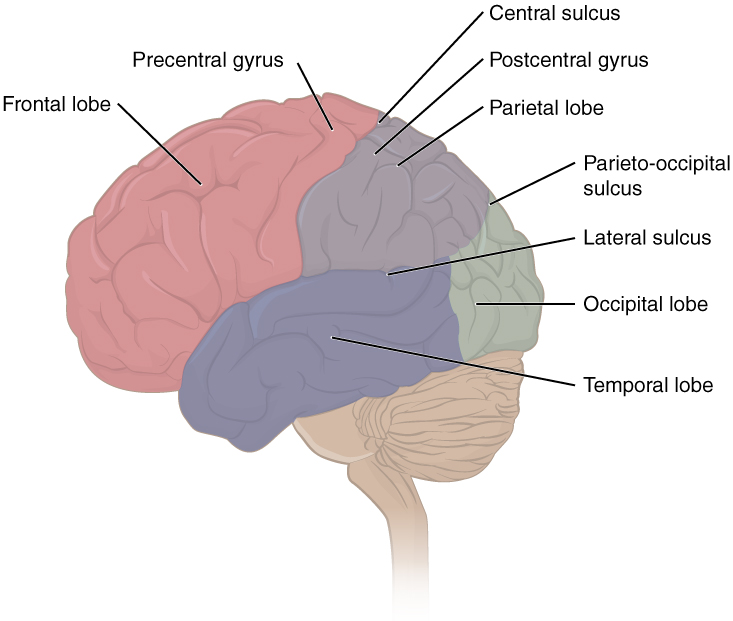

The cerebrum is covered by a continuous layer of gray matter that wraps around either side of the forebrain—the cerebral cortex. This thin, extensive region of wrinkled gray matter is responsible for the higher functions of the nervous system. A gyrus (plural = gyri) is the ridge of one of those wrinkles, and a sulcus (plural = sulci) is the groove between two gyri. The pattern of these folds of tissue indicates specific regions of the cerebral cortex. The head is limited by the size of the birth canal, and the brain must fit inside the cranial cavity of the skull. Extensive folding in the cerebral cortex enables more gray matter to fit into this limited space. If the gray matter of the cortex were peeled off of the cerebrum and laid out flat, its surface area would be roughly equal to one square meter. The folding of the cortex maximizes the amount of gray matter in the cranial cavity. During embryonic development, as the telencephalon expands within the skull, the brain goes through a regular course of growth that results in everyone’s brain having a similar pattern of folds. The surface of the brain can be mapped on the basis of the locations of large gyri and sulci. Using these landmarks, the cortex can be separated into four major regions, or lobes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lobes of the Cerebral Cortex. The cerebral cortex is divided into four lobes. Extensive folding increases the surface area available for cerebral functions.

The lateral sulcus that separates the temporal lobe from the other regions is one such landmark. Superior to the lateral sulcus are the parietal lobe and frontal lobe, which are separated from each other by the central sulcus. The posterior region of the cortex is the occipital lobe, which has no obvious anatomical border between it and the parietal or temporal lobes on the lateral surface of the brain. From the medial surface, an obvious landmark separating the parietal and occipital lobes is called the parieto-occipital sulcus. The fact that there is no obvious anatomical border between these lobes is consistent with the functions of these regions being interrelated.

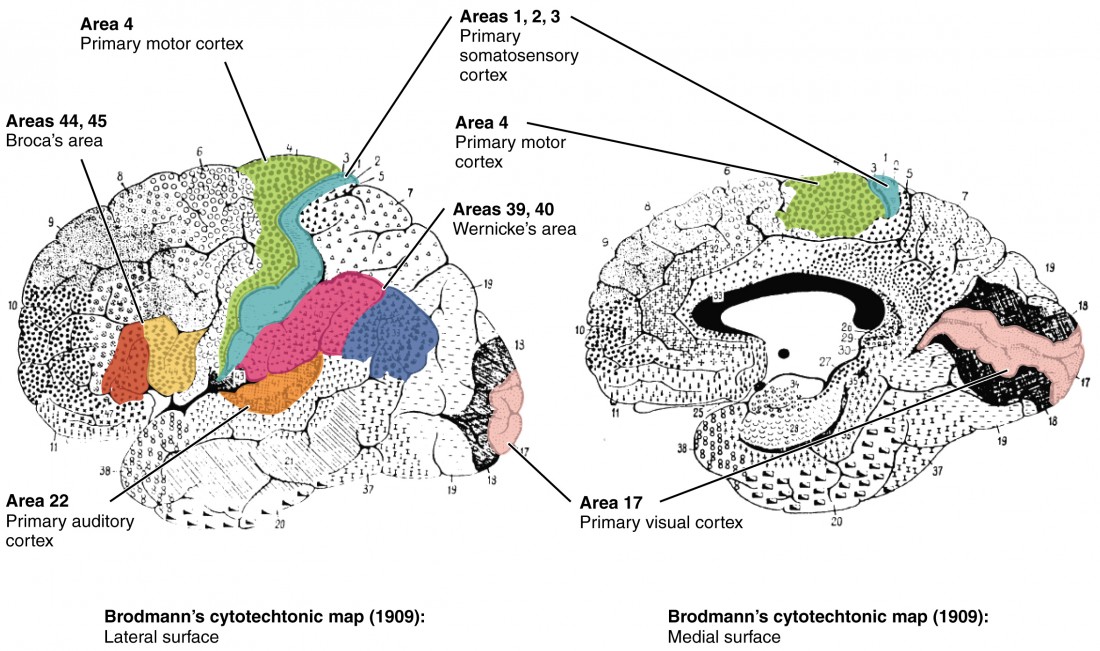

Different regions of the cerebral cortex can be associated with particular functions, a concept known as localization of function. In the early 1900s, a German neuroscientist named Korbinian Brodmann performed an extensive study of the microscopic anatomy—the cytoarchitecture—of the cerebral cortex and divided the cortex into 52 separate regions on the basis of the histology of the cortex. His work resulted in a system of classification known as Brodmann’s areas, which is still used today to describe the anatomical distinctions within the cortex (Figure 3). The results from Brodmann’s work on the anatomy align very well with the functional differences within the cortex. Areas 17 and 18 in the occipital lobe are responsible for primary visual perception. That visual information is complex, so it is processed in the temporal and parietal lobes as well. The temporal lobe is associated with primary auditory sensation, known as Brodmann’s areas 41 and 42 in the superior temporal lobe.

Figure 3. Brodmann’s Areas of the Cerebral Cortex. Brodmann mapping of functionally distinct regions of the cortex was based on its cytoarchitecture at a microscopic level.

Because regions of the temporal lobe are part of the limbic system, memory is an important function associated with that lobe. Memory is essentially a sensory function; memories are recalled sensations such as the smell of Mom’s baking or the sound of a barking dog. Even memories of movement are really the memory of sensory feedback from those movements, such as stretching muscles or the movement of the skin around a joint. Structures in the temporal lobe are responsible for establishing long-term memory, but the ultimate location of those memories is usually in the region in which the sensory perception was processed. The main sensation associated with the parietal lobe is somatosensation, meaning the general sensations associated with the body.

Posterior to the central sulcus is the postcentral gyrus, the primary somatosensory cortex, which is identified as Brodmann’s areas 1, 2, and 3. All of the tactile senses are processed in this area, including touch, pressure, tickle, pain, itch, and vibration, as well as more general senses of the body such as proprioception and kinesthesia, which are the senses of body position and movement, respectively.

Anterior to the central sulcus is the frontal lobe, which is primarily associated with motor functions. The precentral gyrus is the primary motor cortex. Cells from this region of the cerebral cortex are the upper motor neurons that instruct cells in the spinal cord to move skeletal muscles.

Anterior to this region are a few areas that are associated with planned movements. The premotor area is responsible for thinking of a movement to be made. The frontal eye fields are important in eliciting eye movements and in attending to visual stimuli. Broca’s area is responsible for the production of language, or controlling movements responsible for speech; in the vast majority of people, it is located only on the left side. Anterior to these regions is the prefrontal lobe, which serves cognitive functions that can be the basis of personality, short-term memory, and consciousness. The prefrontal lobotomy is an outdated mode of treatment for personality disorders (psychiatric conditions) that profoundly affected the personality of the patient.

Subcortical Structures

Figure 4. Frontal Section of Cerebral Cortex and Basal Nuclei. The major components of the basal nuclei, shown in a frontal section of the brain, are the caudate (just lateral to the lateral ventricle), the putamen (inferior to the caudate and separated by the large white-matter structure called the internal capsule), and the globus pallidus (medial to the putamen).

Beneath the cerebral cortex are sets of nuclei known as subcortical nuclei that augment cortical processes. The nuclei of the basal forebrain serve as the primary location for acetylcholine production, which modulates the overall activity of the cortex, possibly leading to greater attention to sensory stimuli. Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a loss of neurons in the basal forebrain.

The hippocampus and amygdala are medial-lobe structures that, along with the adjacent cortex, are involved in long-term memory formation and emotional responses. The basal nuclei are a set of nuclei in the cerebrum responsible for comparing cortical processing with the general state of activity in the nervous system to influence the likelihood of movement taking place. For example, while a student is sitting in a classroom listening to a lecture, the basal nuclei will keep the urge to jump up and scream from actually happening. (The basal nuclei are also referred to as the basal ganglia, although that is potentially confusing because the term ganglia is typically used for peripheral structures.)

The major structures of the basal nuclei that control movement are the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus, which are located deep in the cerebrum. The caudate is a long nucleus that follows the basic C-shape of the cerebrum from the frontal lobe, through the parietal and occipital lobes, into the temporal lobe. The putamen is mostly deep in the anterior regions of the frontal and parietal lobes. Together, the caudate and putamen are called the striatum. The globus pallidus is a layered nucleus that lies just medial to the putamen; they are called the lenticular nuclei because they look like curved pieces fitting together like lenses. The globus pallidus has two subdivisions, the external and internal segments, which are lateral and medial, respectively. These nuclei are depicted in a frontal section of the brain in Figure 4.

Figure 5. Connections of Basal Nuclei. Input to the basal nuclei is from the cerebral cortex, which is an excitatory connection releasing glutamate as a neurotransmitter. This input is to the striatum, or the caudate and putamen. In the direct pathway, the striatum projects to the internal segment of the globus pallidus and the substantia nigra pars reticulata (GPi/SNr). This is an inhibitory pathway, in which GABA is released at the synapse, and the target cells are hyperpolarized and less likely to fire. The output from the basal nuclei is to the thalamus, which is an inhibitory projection using GABA.

The basal nuclei in the cerebrum are connected with a few more nuclei in the brain stem that together act as a functional group that forms a motor pathway. Two streams of information processing take place in the basal nuclei. All input to the basal nuclei is from the cortex into the striatum (Figure 5).

The direct pathway is the projection of axons from the striatum to the globus pallidus internal segment (GPi) and the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr). The GPi/SNr then projects to the thalamus, which projects back to the cortex. The indirect pathway is the projection of axons from the striatum to the globus pallidus external segment (GPe), then to the subthalamic nucleus (STN), and finally to GPi/SNr. The two streams both target the GPi/SNr, but one has a direct projection and the other goes through a few intervening nuclei. The direct pathway causes the disinhibition of the thalamus (inhibition of one cell on a target cell that then inhibits the first cell), whereas the indirect pathway causes, or reinforces, the normal inhibition of the thalamus. The thalamus then can either excite the cortex (as a result of the direct pathway) or fail to excite the cortex (as a result of the indirect pathway).

The switch between the two pathways is the substantia nigra pars compacta, which projects to the striatum and releases the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine receptors are either excitatory (D1-type receptors) or inhibitory (D2-type receptors). The direct pathway is activated by dopamine, and the indirect pathway is inhibited by dopamine.

When the substantia nigra pars compacta is firing, it signals to the basal nuclei that the body is in an active state, and movement will be more likely. When the substantia nigra pars compacta is silent, the body is in a passive state, and movement is inhibited. To illustrate this situation, while a student is sitting listening to a lecture, the substantia nigra pars compacta would be silent and the student less likely to get up and walk around. Likewise, while the professor is lecturing, and walking around at the front of the classroom, the professor’s substantia nigra pars compacta would be active, in keeping with his or her activity level.

Watch this video to learn about the basal nuclei (also known as the basal ganglia), which have two pathways that process information within the cerebrum.

As shown in this video, the direct pathway is the shorter pathway through the system that results in increased activity in the cerebral cortex and increased motor activity. The direct pathway is described as resulting in “disinhibition” of the thalamus. What does disinhibition mean? What are the two neurons doing individually to cause this?

Everyday Connections: The Myth of Left Brain/Right Brain

There is a persistent myth that people are “right-brained” or “left-brained,” which is an oversimplification of an important concept about the cerebral hemispheres. There is some lateralization of function, in which the left side of the brain is devoted to language function and the right side is devoted to spatial and nonverbal reasoning. Whereas these functions are predominantly associated with those sides of the brain, there is no monopoly by either side on these functions. Many pervasive functions, such as language, are distributed globally around the cerebrum. Some of the support for this misconception has come from studies of split brains.

A drastic way to deal with a rare and devastating neurological condition (intractable epilepsy) is to separate the two hemispheres of the brain. After sectioning the corpus callosum, a split-brained patient will have trouble producing verbal responses on the basis of sensory information processed on the right side of the cerebrum, leading to the idea that the left side is responsible for language function. However, there are well-documented cases of language functions lost from damage to the right side of the brain.

The deficits seen in damage to the left side of the brain are classified as aphasia, a loss of speech function; damage on the right side can affect the use of language. Right-side damage can result in a loss of ability to understand figurative aspects of speech, such as jokes, irony, or metaphors. Nonverbal aspects of speech can be affected by damage to the right side, such as facial expression or body language, and right-side damage can lead to a “flat affect” in speech, or a loss of emotional expression in speech—sounding like a robot when talking.

The Diencephalon

Figure 6. The Diencephalon. The diencephalon is composed primarily of the thalamus and hypothalamus, which together define the walls of the third ventricle. The thalami are two elongated, ovoid structures on either side of the midline that make contact in the middle. The hypothalamus is inferior and anterior to the thalamus, culminating in a sharp angle to which the pituitary gland is attached.

The diencephalon is the one region of the adult brain that retains its name from embryologic development. The etymology of the word diencephalon translates to “through brain.” It is the connection between the cerebrum and the rest of the nervous system, with one exception. The rest of the brain, the spinal cord, and the PNS all send information to the cerebrum through the diencephalon. Output from the cerebrum passes through the diencephalon. The single exception is the system associated with olfaction, or the sense of smell, which connects directly with the cerebrum. In the earliest vertebrate species, the cerebrum was not much more than olfactory bulbs that received peripheral information about the chemical environment (to call it smell in these organisms is imprecise because they lived in the ocean). The diencephalon is deep beneath the cerebrum and constitutes the walls of the third ventricle. The diencephalon can be described as any region of the brain with “thalamus” in its name. The two major regions of the diencephalon are the thalamus itself and the hypothalamus (Figure 6). There are other structures, such as the epithalamus, which contains the pineal gland, or the subthalamus, which includes the subthalamic nucleus that is part of the basal nuclei.

Thalamus

The thalamus is a collection of nuclei that relay information between the cerebral cortex and the periphery, spinal cord, or brain stem. All sensory information, except for the sense of smell, passes through the thalamus before processing by the cortex. Axons from the peripheral sensory organs, or intermediate nuclei, synapse in the thalamus, and thalamic neurons project directly to the cerebrum. It is a requisite synapse in any sensory pathway, except for olfaction. The thalamus does not just pass the information on, it also processes that information. For example, the portion of the thalamus that receives visual information will influence what visual stimuli are important, or what receives attention. The cerebrum also sends information down to the thalamus, which usually communicates motor commands. This involves interactions with the cerebellum and other nuclei in the brain stem. The cerebrum interacts with the basal nuclei, which involves connections with the thalamus. The primary output of the basal nuclei is to the thalamus, which relays that output to the cerebral cortex. The cortex also sends information to the thalamus that will then influence the effects of the basal nuclei.

Hypothalamus

Inferior and slightly anterior to the thalamus is the hypothalamus, the other major region of the diencephalon. The hypothalamus is a collection of nuclei that are largely involved in regulating homeostasis. The hypothalamus is the executive region in charge of the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system through its regulation of the anterior pituitary gland. Other parts of the hypothalamus are involved in memory and emotion as part of the limbic system.

Brain Stem

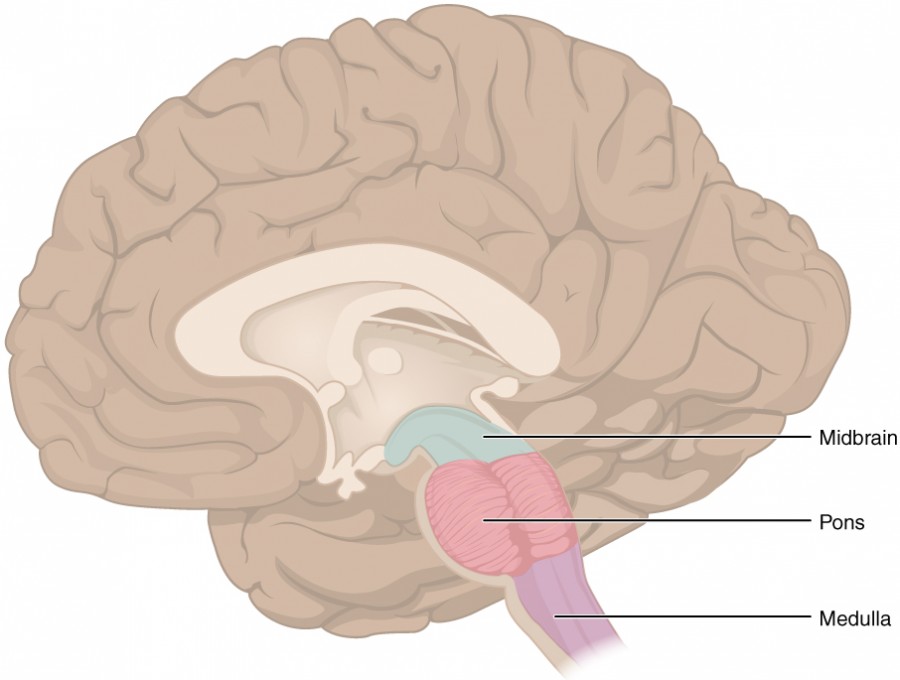

Figure 7. The Brain Stem. The brain stem comprises three regions: the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla.

The midbrain and hindbrain (composed of the pons and the medulla) are collectively referred to as the brain stem (Figure 7). The structure emerges from the ventral surface of the forebrain as a tapering cone that connects the brain to the spinal cord. Attached to the brain stem, but considered a separate region of the adult brain, is the cerebellum. The midbrain coordinates sensory representations of the visual, auditory, and somatosensory perceptual spaces. The pons is the main connection with the cerebellum. The pons and the medulla regulate several crucial functions, including the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and rates.

The cranial nerves connect through the brain stem and provide the brain with the sensory input and motor output associated with the head and neck, including most of the special senses. The major ascending and descending pathways between the spinal cord and brain, specifically the cerebrum, pass through the brain stem.

Midbrain

One of the original regions of the embryonic brain, the midbrain is a small region between the thalamus and pons. It is separated into the tectum and tegmentum, from the Latin words for roof and floor, respectively. The cerebral aqueduct passes through the center of the midbrain, such that these regions are the roof and floor of that canal. The tectum is composed of four bumps known as the colliculi (singular = colliculus), which means “little hill” in Latin. The inferior colliculus is the inferior pair of these enlargements and is part of the auditory brain stem pathway. Neurons of the inferior colliculus project to the thalamus, which then sends auditory information to the cerebrum for the conscious perception of sound. The superior colliculus is the superior pair and combines sensory information about visual space, auditory space, and somatosensory space. Activity in the superior colliculus is related to orienting the eyes to a sound or touch stimulus. If you are walking along the sidewalk on campus and you hear chirping, the superior colliculus coordinates that information with your awareness of the visual location of the tree right above you. That is the correlation of auditory and visual maps. If you suddenly feel something wet fall on your head, your superior colliculus integrates that with the auditory and visual maps and you know that the chirping bird just relieved itself on you. You want to look up to see the culprit, but do not. The tegmentum is continuous with the gray matter of the rest of the brain stem. Throughout the midbrain, pons, and medulla, the tegmentum contains the nuclei that receive and send information through the cranial nerves, as well as regions that regulate important functions such as those of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems.

Pons

The word pons comes from the Latin word for bridge. It is visible on the anterior surface of the brain stem as the thick bundle of white matter attached to the cerebellum. The pons is the main connection between the cerebellum and the brain stem. The bridge-like white matter is only the anterior surface of the pons; the gray matter beneath that is a continuation of the tegmentum from the midbrain. Gray matter in the tegmentum region of the pons contains neurons receiving descending input from the forebrain that is sent to the cerebellum.

Medulla

The medulla is the region known as the myelencephalon in the embryonic brain. The initial portion of the name, “myel,” refers to the significant white matter found in this region—especially on its exterior, which is continuous with the white matter of the spinal cord. The tegmentum of the midbrain and pons continues into the medulla because this gray matter is responsible for processing cranial nerve information. A diffuse region of gray matter throughout the brain stem, known as the reticular formation, is related to sleep and wakefulness, such as general brain activity and attention.

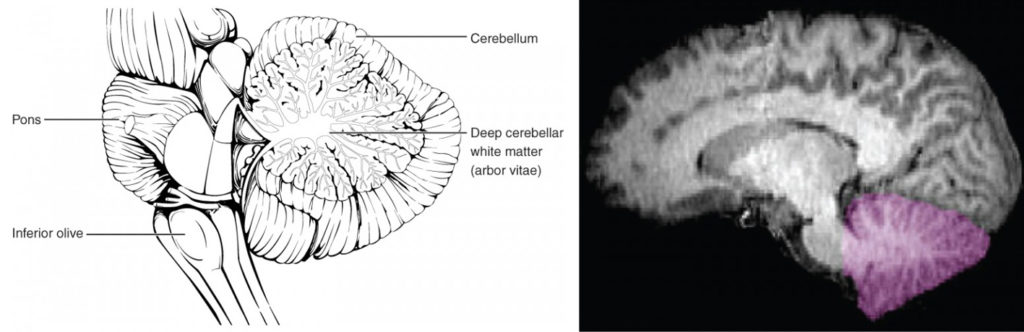

The Cerebellum

The cerebellum, as the name suggests, is the “little brain.” It is covered in gyri and sulci like the cerebrum, and looks like a miniature version of that part of the brain (Figure 8). The cerebellum is largely responsible for comparing information from the cerebrum with sensory feedback from the periphery through the spinal cord. It accounts for approximately 10 percent of the mass of the brain.

Figure 8. The Cerebellum. The cerebellum is situated on the posterior surface of the brain stem. Descending input from the cerebellum enters through the large white matter structure of the pons. Ascending input from the periphery and spinal cord enters through the fibers of the inferior olive. Output goes to the midbrain, which sends a descending signal to the spinal cord.

Descending fibers from the cerebrum have branches that connect to neurons in the pons. Those neurons project into the cerebellum, providing a copy of motor commands sent to the spinal cord. Sensory information from the periphery, which enters through spinal or cranial nerves, is copied to a nucleus in the medulla known as the inferior olive. Fibers from this nucleus enter the cerebellum and are compared with the descending commands from the cerebrum. If the primary motor cortex of the frontal lobe sends a command down to the spinal cord to initiate walking, a copy of that instruction is sent to the cerebellum. Sensory feedback from the muscles and joints, proprioceptive information about the movements of walking, and sensations of balance are sent to the cerebellum through the inferior olive and the cerebellum compares them. If walking is not coordinated, perhaps because the ground is uneven or a strong wind is blowing, then the cerebellum sends out a corrective command to compensate for the difference between the original cortical command and the sensory feedback. The output of the cerebellum is into the midbrain, which then sends a descending input to the spinal cord to correct the messages going to skeletal muscles.

The Spinal Cord

The description of the CNS is concentrated on the structures of the brain, but the spinal cord is another major organ of the system. Whereas the brain develops out of expansions of the neural tube into primary and then secondary vesicles, the spinal cord maintains the tube structure and is only specialized into certain regions. As the spinal cord continues to develop in the newborn, anatomical features mark its surface. The anterior midline is marked by the anterior median fissure, and the posterior midline is marked by the posterior median sulcus. Axons enter the posterior side through the dorsal (posterior) nerve root, which marks the posterolateral sulcus on either side. The axons emerging from the anterior side do so through the ventral (anterior) nerve root. Note that it is common to see the terms dorsal (dorsal = “back”) and ventral (ventral = “belly”) used interchangeably with posterior and anterior, particularly in reference to nerves and the structures of the spinal cord. You should learn to be comfortable with both.

On the whole, the posterior regions are responsible for sensory functions and the anterior regions are associated with motor functions. This comes from the initial development of the spinal cord, which is divided into the basal plate and the alar plate. The basal plate is closest to the ventral midline of the neural tube, which will become the anterior face of the spinal cord and gives rise to motor neurons. The alar plate is on the dorsal side of the neural tube and gives rise to neurons that will receive sensory input from the periphery. The length of the spinal cord is divided into regions that correspond to the regions of the vertebral column. The name of a spinal cord region corresponds to the level at which spinal nerves pass through the intervertebral foramina.

Immediately adjacent to the brain stem is the cervical region, followed by the thoracic, then the lumbar, and finally the sacral region. The spinal cord is not the full length of the vertebral column because the spinal cord does not grow significantly longer after the first or second year, but the skeleton continues to grow. The nerves that emerge from the spinal cord pass through the intervertebral formina at the respective levels. As the vertebral column grows, these nerves grow with it and result in a long bundle of nerves that resembles a horse’s tail and is named the cauda equina. The sacral spinal cord is at the level of the upper lumbar vertebral bones. The spinal nerves extend from their various levels to the proper level of the vertebral column.

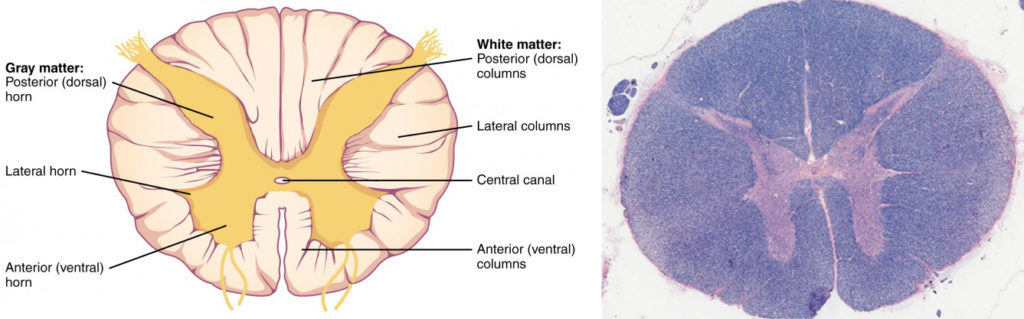

Gray Horns

In cross-section, the gray matter of the spinal cord has the appearance of an ink-blot test, with the spread of the gray matter on one side replicated on the other—a shape reminiscent of a bulbous capital “H.” As shown in Figure 9, the gray matter is subdivided into regions that are referred to as horns. The posterior horn is responsible for sensory processing. The anterior horn sends out motor signals to the skeletal muscles. The lateral horn, which is only found in the thoracic, upper lumbar, and sacral regions, is the central component of the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. Some of the largest neurons of the spinal cord are the multipolar motor neurons in the anterior horn. The fibers that cause contraction of skeletal muscles are the axons of these neurons. The motor neuron that causes contraction of the big toe, for example, is located in the sacral spinal cord. The axon that has to reach all the way to the belly of that muscle may be a meter in length. The neuronal cell body that maintains that long fiber must be quite large, possibly several hundred micrometers in diameter, making it one of the largest cells in the body.

Figure 9. Cross-section of Spinal Cord. The cross-section of a thoracic spinal cord segment shows the posterior, anterior, and lateral horns of gray matter, as well as the posterior, anterior, and lateral columns of white matter. LM × 40. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

White Columns

Just as the gray matter is separated into horns, the white matter of the spinal cord is separated into columns. Ascending tracts of nervous system fibers in these columns carry sensory information up to the brain, whereas descending tracts carry motor commands from the brain. Looking at the spinal cord longitudinally, the columns extend along its length as continuous bands of white matter. Between the two posterior horns of gray matter are the posterior columns. Between the two anterior horns, and bounded by the axons of motor neurons emerging from that gray matter area, are the anterior columns. The white matter on either side of the spinal cord, between the posterior horn and the axons of the anterior horn neurons, are the lateral columns. The posterior columns are composed of axons of ascending tracts. The anterior and lateral columns are composed of many different groups of axons of both ascending and descending tracts—the latter carrying motor commands down from the brain to the spinal cord to control output to the periphery.

Watch this video to learn about the gray matter of the spinal cord that receives input from fibers of the dorsal (posterior) root and sends information out through the fibers of the ventral (anterior) root.

As discussed in this video, these connections represent the interactions of the CNS with peripheral structures for both sensory and motor functions. The cervical and lumbar spinal cords have enlargements as a result of larger populations of neurons. What are these enlargements responsible for?

Disorders of the Basal Nuclei

Parkinson’s disease is a disorder of the basal nuclei, specifically of the substantia nigra, that demonstrates the effects of the direct and indirect pathways. Parkinson’s disease is the result of neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta dying. These neurons release dopamine into the striatum. Without that modulatory influence, the basal nuclei are stuck in the indirect pathway, without the direct pathway being activated. The direct pathway is responsible for increasing cortical movement commands. The increased activity of the indirect pathway results in the hypokinetic disorder of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s disease is neurodegenerative, meaning that neurons die that cannot be replaced, so there is no cure for the disorder. Treatments for Parkinson’s disease are aimed at increasing dopamine levels in the striatum. Currently, the most common way of doing that is by providing the amino acid L-DOPA, which is a precursor to the neurotransmitter dopamine and can cross the blood-brain barrier. With levels of the precursor elevated, the remaining cells of the substantia nigra pars compacta can make more neurotransmitter and have a greater effect. Unfortunately, the patient will become less responsive to L-DOPA treatment as time progresses, and it can cause increased dopamine levels elsewhere in the brain, which are associated with psychosis or schizophrenia.

Visit this site for a thorough explanation of Parkinson’s disease.

Compared with the nearest evolutionary relative, the chimpanzee, the human has a brain that is huge. At a point in the past, a common ancestor gave rise to the two species of humans and chimpanzees. That evolutionary history is long and is still an area of intense study. But something happened to increase the size of the human brain relative to the chimpanzee. Read this article in which the author explores the current understanding of why this happened. According to one hypothesis about the expansion of brain size, what tissue might have been sacrificed so energy was available to grow our larger brain? Based on what you know about that tissue and nervous tissue, why would there be a trade-off between them in terms of energy use?

Candela Citations

- Chapter 13. Authored by: OpenStax College. Provided by: Rice University. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/files/textbook_version/low_res_pdf/13/col11496-lr.pdf. Project: Anatomy & Physiology. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11496/latest/.