Learning Outcomes

- Solve problems involving exponential growth.

- Solve problems involving radioactive decay, carbon dating, and half-life.

- Use the compound interest formula.

In this section, we explore some important applications of exponential and logarithmic functions, including radioactive isotopes and compound interest.

A nuclear research reactor inside the Neely Nuclear Research Center on the Georgia Institute of Technology campus. (credit: Georgia Tech Research Institute)

Exponential Growth and Decay

In real-world applications, we need to model the behavior of a function. In mathematical modeling, we choose a familiar general function with properties that suggest that it will model the real-world phenomenon we wish to analyze. In the case of rapid growth, we may choose the exponential growth function:

[latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}[/latex]

where [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is equal to the value at time zero, e is Euler’s constant, and k is a positive constant that determines the rate (percentage) of growth. We may use the exponential growth function in applications involving doubling time, the time it takes for a quantity to double. Such phenomena as wildlife populations, financial investments, biological samples, and natural resources may exhibit growth based odn a doubling time. In some applications, however, as we will see when we discuss the logistic equation, the logistic model sometimes fits the data better than the exponential model.

On the other hand, if a quantity is falling rapidly toward zero, without ever reaching zero, then we should probably choose the exponential decay model. Again, we have the form [latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{-kt}[/latex] where [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is the starting value, and e is Euler’s constant. Now k is a negative constant that determines the rate of decay. We may use the exponential decay model when we are calculating half-life, or the time it takes for a substance to exponentially decay to half of its original quantity. We use half-life in applications involving radioactive isotopes.

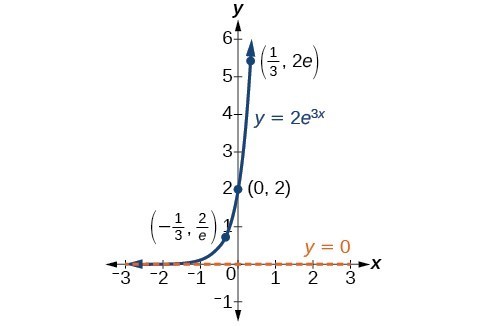

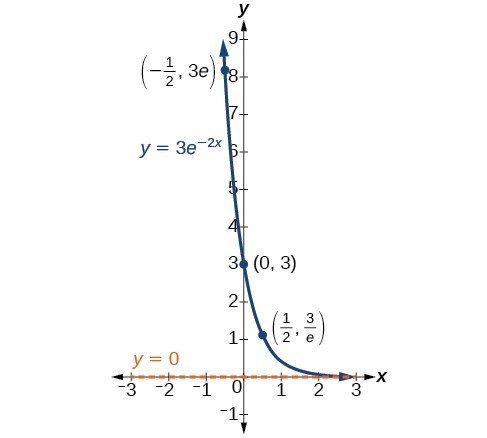

In our choice of a function to serve as a mathematical model, we often use data points gathered by careful observation and measurement to construct points on a graph and hope we can recognize the shape of the graph. Exponential growth and decay graphs have a distinctive shape, as we can see in the graphs below. It is important to remember that, although parts of each of the two graphs seem to lie on the x-axis, they are really a tiny distance above the x-axis.

A graph showing exponential growth. The equation is [latex]y=2{e}^{3x}[/latex].

A graph showing exponential decay. The equation is [latex]y=3{e}^{-2x}[/latex].

Exponential growth and decay often involve very large or very small numbers. To describe these numbers, we often use orders of magnitude. The order of magnitude is the power of ten when the number is expressed in scientific notation with one digit to the left of the decimal. For example, the distance to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, measured in kilometers, is 40,113,497,200,000 kilometers. Expressed in scientific notation, this is [latex]4.01134972\times {10}^{13}[/latex]. We could describe this number as having order of magnitude [latex]{10}^{13}[/latex].

A General Note: Characteristics of the Exponential Function [latex]y=A_{0}e^{kt}[/latex]

An exponential function of the form [latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}[/latex] has the following characteristics:

- one-to-one function

- horizontal asymptote: y = 0

- domain: [latex]\left(-\infty , \infty \right)[/latex]

- range: [latex]\left(0,\infty \right)[/latex]

- x intercept: none

- y-intercept: [latex]\left(0,{A}_{0}\right)[/latex]

- increasing if k > 0

- decreasing if k < 0

An exponential function models exponential growth when k > 0 and exponential decay when k < 0.

Example: Graphing Exponential Growth

A population of bacteria doubles every hour. If the culture started with 10 bacteria, graph the population as a function of time.

Calculating Doubling Time

For growing quantities, we might want to find out how long it takes for a quantity to double. As we mentioned above, the time it takes for a quantity to double is called the doubling time.

Given the basic exponential growth equation [latex]A={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}[/latex], doubling time can be found by solving for when the original quantity has doubled, that is, by solving [latex]2{A}_{0}={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}[/latex].

The formula is derived as follows:

[latex]\begin{array}{l}2{A}_{0}={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}\hfill & \hfill \\ 2={e}^{kt}\hfill & \text{Divide both sides by }{A}_{0}.\hfill \\ \mathrm{ln}2=kt\hfill & \text{Take the natural logarithm of both sides}.\hfill \\ t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}2}{k}\hfill & \text{Divide by the coefficient of }t.\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

Thus the doubling time is

[latex]t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}2}{k}[/latex]

Example: Finding a Function That Describes Exponential Growth

According to Moore’s Law, the doubling time for the number of transistors that can be put on a computer chip is approximately two years. Give a function that describes this behavior.

Try It

Recent data suggests that, as of 2013, the rate of growth predicted by Moore’s Law no longer holds. Growth has slowed to a doubling time of approximately three years. Find the new function that takes that longer doubling time into account.

Half-Life

We now turn to exponential decay. One of the common terms associated with exponential decay, as stated above, is half-life, the length of time it takes an exponentially decaying quantity to decrease to half its original amount. Every radioactive isotope has a half-life, and the process describing the exponential decay of an isotope is called radioactive decay.

To find the half-life of a function describing exponential decay, solve the following equation:

[latex]\frac{1}{2}{A}_{0}={A}_{o}{e}^{kt}[/latex]

We find that the half-life depends only on the constant k and not on the starting quantity [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex].

The formula is derived as follows

[latex]\begin{array}{l}\frac{1}{2}{A}_{0}={A}_{o}{e}^{kt}\hfill & \hfill \\ \frac{1}{2}={e}^{kt}\hfill & \text{Divide both sides by }{A}_{0}.\hfill \\ \mathrm{ln}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)=kt\hfill & \text{Take the natural log of both sides}.\hfill \\ -\mathrm{ln}\left(2\right)=kt\hfill & \text{Apply properties of logarithms}.\hfill \\ -\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(2\right)}{k}=t\hfill & \text{Divide by }k.\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

Since t, the time, is positive, k must, as expected, be negative. This gives us the half-life formula

[latex]t=-\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(2\right)}{k}[/latex]

In previous sections, we learned the properties and rules for both exponential and logarithmic functions. We have seen that any exponential function can be written as a logarithmic function and vice versa. We have used exponents to solve logarithmic equations and logarithms to solve exponential equations. We are now ready to combine our skills to solve equations that model real-world situations, whether the unknown is in an exponent or in the argument of a logarithm.

One such application is in science, in calculating the time it takes for half of the unstable material in a sample of a radioactive substance to decay, called its half-life. The table below lists the half-life for several of the more common radioactive substances.

| Substance | Use | Half-life |

|---|---|---|

| gallium-67 | nuclear medicine | 80 hours |

| cobalt-60 | manufacturing | 5.3 years |

| technetium-99m | nuclear medicine | 6 hours |

| americium-241 | construction | 432 years |

| carbon-14 | archeological dating | 5,715 years |

| uranium-235 | atomic power | 703,800,000 years |

We can see how widely the half-lives for these substances vary. Knowing the half-life of a substance allows us to calculate the amount remaining after a specified time. We can use the formula for radioactive decay:

[latex]\begin{array}{l}A\left(t\right)={A}_{0}{e}^{\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(0.5\right)}{T}t}\hfill \\ A\left(t\right)={A}_{0}{e}^{\mathrm{ln}\left(0.5\right)\frac{t}{T}}\hfill \\ A\left(t\right)={A}_{0}{\left({e}^{\mathrm{ln}\left(0.5\right)}\right)}^{\frac{t}{T}}\hfill \\ A\left(t\right)={A}_{0}{\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}^{\frac{t}{T}}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

where

- [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is the amount initially present

- T is the half-life of the substance

- t is the time period over which the substance is studied

- y is the amount of the substance present after time t

How To: Given the half-life, find the decay rate

- Write [latex]A={A}_{o}{e}^{kt}[/latex].

- Replace A by [latex]\frac{1}{2}{A}_{0}[/latex] and replace t by the given half-life.

- Solve to find k. Express k as an exact value (do not round).

Note: It is also possible to find the decay rate using [latex]k=-\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(2\right)}{t}[/latex].

Example: Using the Formula for Radioactive Decay to Find the Quantity of a Substance

How long will it take for 10% of a 1000-gram sample of uranium-235 to decay?

Try It

How long will it take before twenty percent of our 1000-gram sample of uranium-235 has decayed?

Example: Finding the Function that Describes Radioactive Decay

The half-life of carbon-14 is 5,730 years. Express the amount of carbon-14 remaining as a function of time, t.

Try It

The half-life of plutonium-244 is 80,000,000 years. Find a function that gives the amount of carbon-14 remaining as a function of time measured in years.

Radiocarbon Dating

The formula for radioactive decay is important in radiocarbon dating which is used to calculate the approximate date a plant or animal died. Radiocarbon dating was discovered in 1949 by Willard Libby who won a Nobel Prize for his discovery. It compares the difference between the ratio of two isotopes of carbon in an organic artifact or fossil to the ratio of those two isotopes in the air. It is believed to be accurate to within about 1% error for plants or animals that died within the last 60,000 years.

Carbon-14 is a radioactive isotope of carbon that has a half-life of 5,730 years. It occurs in small quantities in the carbon dioxide in the air we breathe. Most of the carbon on Earth is carbon-12 which has an atomic weight of 12 and is not radioactive. Scientists have determined the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 in the air for the last 60,000 years using tree rings and other organic samples of known dates—although the ratio has changed slightly over the centuries.

As long as a plant or animal is alive, the ratio of the two isotopes of carbon in its body is close to the ratio in the atmosphere. When it dies, the carbon-14 in its body decays and is not replaced. By comparing the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 in a decaying sample to the known ratio in the atmosphere, the date the plant or animal died can be approximated.

Since the half-life of carbon-14 is 5,730 years, the formula for the amount of carbon-14 remaining after t years is

[latex]A\approx {A}_{0}{e}^{\left(\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(0.5\right)}{5730}\right)t}[/latex]

where

- A is the amount of carbon-14 remaining

- [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is the amount of carbon-14 when the plant or animal began decaying.

This formula is derived as follows:

[latex]\begin{array}{l}\text{ }A={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}\hfill & \text{The continuous growth formula}.\hfill \\ \text{ }0.5{A}_{0}={A}_{0}{e}^{k\cdot 5730}\hfill & \text{Substitute the half-life for }t\text{ and }0.5{A}_{0}\text{ for }f\left(t\right).\hfill \\ \text{ }0.5={e}^{5730k}\hfill & \text{Divide both sides by }{A}_{0}.\hfill \\ \mathrm{ln}\left(0.5\right)=5730k\hfill & \text{Take the natural log of both sides}.\hfill \\ \text{ }k=\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(0.5\right)}{5730}\hfill & \text{Divide both sides by the coefficient of }k.\hfill \\ \text{ }A={A}_{0}{e}^{\left(\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(0.5\right)}{5730}\right)t}\hfill & \text{Substitute for }r\text{ in the continuous growth formula}.\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

To find the age of an object we solve this equation for t:

[latex]t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(\frac{A}{{A}_{0}}\right)}{-0.000121}[/latex]

Out of necessity, we neglect here the many details that a scientist takes into consideration when doing carbon-14 dating, and we only look at the basic formula. The ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 in the atmosphere is approximately 0.0000000001%. Let r be the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 in the organic artifact or fossil to be dated determined by a method called liquid scintillation. From the equation [latex]A\approx {A}_{0}{e}^{-0.000121t}[/latex] we know the ratio of the percentage of carbon-14 in the object we are dating to the percentage of carbon-14 in the atmosphere is [latex]r=\frac{A}{{A}_{0}}\approx {e}^{-0.000121t}[/latex]. We solve this equation for t, to get

[latex]t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(r\right)}{-0.000121}[/latex]

How To: Given the percentage of carbon-14 in an object, determine its age

- Express the given percentage of carbon-14 as an equivalent decimal r.

- Substitute for r in the equation [latex]t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(r\right)}{-0.000121}[/latex] and solve for the age, t.

Example: Finding the Age of a Bone

A bone fragment is found that contains 20% of its original carbon-14. To the nearest year, how old is the bone?

Try It

Cesium-137 has a half-life of about 30 years. If we begin with 200 mg of cesium-137, will it take more or less than 230 years until only 1 milligram remains?

Using the Compound Interest Formula

Savings instruments in which earnings are continually reinvested, such as mutual funds and retirement accounts, use compound interest. The term compounding refers to interest earned not only on the original value, but on the accumulated value of the account.

The annual percentage rate (APR) of an account, also called the nominal rate, is the yearly interest rate earned by an investment account. The term nominal is used when the compounding occurs a number of times other than once per year. In fact, when interest is compounded more than once a year, the effective interest rate ends up being greater than the nominal rate! This is a powerful tool for investing.

We can calculate compound interest using the compound interest formula which is an exponential function of the variables time t, principal P, APR r, and number of times compounded in a year n:

[latex]A\left(t\right)=P{\left(1+\frac{r}{n}\right)}^{nt}[/latex]

For example, observe the table below, which shows the result of investing $1,000 at 10% for one year. Notice how the value of the account increases as the compounding frequency increases.

| Frequency | Value after 1 year |

|---|---|

| Annually | $1100 |

| Semiannually | $1102.50 |

| Quarterly | $1103.81 |

| Monthly | $1104.71 |

| Daily | $1105.16 |

A General Note: The Compound Interest Formula

Compound interest can be calculated using the formula

[latex]A\left(t\right)=P{\left(1+\frac{r}{n}\right)}^{nt}[/latex]

where

- A(t) is the accumulated value of the account

- t is measured in years

- P is the starting amount of the account, often called the principal, or more generally present value

- r is the annual percentage rate (APR) expressed as a decimal

- n is the number of times compounded in a year

Example: Calculating Compound Interest

If we invest $3,000 in an investment account paying 3% interest compounded quarterly, how much will the account be worth in 10 years?

Try It

An initial investment of $100,000 at 12% interest is compounded weekly (use 52 weeks in a year). What will the investment be worth in 30 years?

Example: Using the Compound Interest Formula to Solve for the Principal

A 529 Plan is a college-savings plan that allows relatives to invest money to pay for a child’s future college tuition; the account grows tax-free. Lily wants to set up a 529 account for her new granddaughter and wants the account to grow to $40,000 over 18 years. She believes the account will earn 6% compounded semi-annually (twice a year). To the nearest dollar, how much will Lily need to invest in the account now?

Try It

Refer to the previous example. To the nearest dollar, how much would Lily need to invest if the account is compounded quarterly?

Choosing an Appropriate Model

Now that we have discussed various mathematical models, we need to learn how to choose the appropriate model for the raw data we have. Many factors influence the choice of a mathematical model among which are experience, scientific laws, and patterns in the data itself. Not all data can be described by elementary functions. Sometimes a function is chosen that approximates the data over a given interval. For instance, suppose data were gathered on the number of homes bought in the United States from the years 1960 to 2013. After plotting these data in a scatter plot, we notice that the shape of the data from the years 2000 to 2013 follow a logarithmic curve. We could restrict the interval from 2000 to 2010, apply regression analysis using a logarithmic model, and use it to predict the number of home buyers for the year 2015.

Three kinds of functions that are often useful in mathematical models are linear functions, exponential functions, and logarithmic functions. If the data lies on a straight line or seems to lie approximately along a straight line, a linear model may be best. If the data is non-linear, we often consider an exponential or logarithmic model although other models, such as quadratic models, may also be considered.

In choosing between an exponential model and a logarithmic model, we look at the way the data curves. This is called the concavity. If we draw a line between two data points, and all (or most) of the data between those two points lies above that line, we say the curve is concave down. We can think of it as a bowl that bends downward and therefore cannot hold water. If all (or most) of the data between those two points lies below the line, we say the curve is concave up. In this case, we can think of a bowl that bends upward and can therefore hold water. An exponential curve, whether rising or falling, whether representing growth or decay, is always concave up away from its horizontal asymptote. A logarithmic curve is always concave down away from its vertical asymptote. In the case of positive data, which is the most common case, an exponential curve is always concave up and a logarithmic curve always concave down.

A logistic curve changes concavity. It starts out concave up and then changes to concave down beyond a certain point, called a point of inflection.

After using the graph to help us choose a type of function to use as a model, we substitute points, and solve to find the parameters. We reduce round-off error by choosing points as far apart as possible.

Example: Choosing a Mathematical Model

Does a linear, exponential, logarithmic, or logistic model best fit the values listed below? Find the model, and use a graph to check your choice.

| x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| y | 0 | 1.386 | 2.197 | 2.773 | 3.219 | 3.584 | 3.892 | 4.159 | 4.394 |

Try It

Does a linear, exponential, or logarithmic model best fit the data in the table below? Find the model.

| x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| y | 3.297 | 5.437 | 8.963 | 14.778 | 24.365 | 40.172 | 66.231 | 109.196 | 180.034 |

Expressing an Exponential Model in Base e

While powers and logarithms of any base can be used in modeling, the two most common bases are [latex]10[/latex] and [latex]e[/latex]. In science and mathematics, the base e is often preferred. We can use properties of exponents and properties of logarithms to change any base to base e.

How To: Given a model with the form [latex]y=a{b}^{x}[/latex], change it to the form [latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{kx}[/latex]

- Rewrite [latex]y=a{b}^{x}[/latex] as [latex]y=a{e}^{\mathrm{ln}\left({b}^{x}\right)}[/latex].

- Use the power rule of logarithms to rewrite as [latex]y=a{e}^{x\mathrm{ln}\left(b\right)}=a{e}^{\mathrm{ln}\left(b\right)x}[/latex].

- Note that [latex]a={A}_{0}[/latex] and [latex]k=\mathrm{ln}\left(b\right)[/latex] in the equation [latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{kx}[/latex].

Example: Changing to base [latex]e[/latex]

Change the function [latex]y=2.5{\left(3.1\right)}^{x}[/latex] so that this same function is written in the form [latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{kx}[/latex].

Try It

Change the function [latex]y=3{\left(0.5\right)}^{x}[/latex] to one having e as the base.

Exponential Regression

As we have learned, there are a multitude of situations that can be modeled by exponential functions, such as investment growth, radioactive decay, atmospheric pressure changes, and temperatures of a cooling object. What do these phenomena have in common? For one thing, all the models either increase or decrease as time moves forward. But that’s not the whole story. It’s the way data increase or decrease that helps us determine whether it is best modeled by an exponential function. Knowing the behavior of exponential functions in general allows us to recognize when to use exponential regression, so let’s review exponential growth and decay.

Recall that exponential functions have the form [latex]y=a{b}^{x}[/latex] or [latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{kx}[/latex]. When performing regression analysis, we use the form most commonly used on graphing utilities, [latex]y=a{b}^{x}[/latex]. Take a moment to reflect on the characteristics we’ve already learned about the exponential function [latex]y=a{b}^{x}[/latex] (assume a > 0):

- b must be greater than zero and not equal to one.

- The initial value of the model is a.

- If b > 1, the function models exponential growth. As x increases, the outputs of the model increase slowly at first, but then increase more and more rapidly, without bound.

- If 0 < b < 1, the function models exponential decay. As x increases, the outputs for the model decrease rapidly at first and then level off to become asymptotic to the x-axis. In other words, the outputs never become equal to or less than zero.

As part of the results, your calculator will display a number known as the correlation coefficient, labeled by the variable r or [latex]{r}^{2}[/latex]. (You may have to change the calculator’s settings for these to be shown.) The values are an indication of the “goodness of fit” of the regression equation to the data. We more commonly use the value of [latex]{r}^{2}[/latex] instead of r, but the closer either value is to 1, the better the regression equation approximates the data.

A General Note: Exponential Regression

Exponential regression is used to model situations in which growth begins slowly and then accelerates rapidly without bound, or where decay begins rapidly and then slows down to get closer and closer to zero. We use the command “ExpReg” on a graphing utility to fit an exponential function to a set of data points. This returns an equation of the form [latex]y=a{b}^{x}[/latex].

Note that:

- b must be non-negative.

- When b > 1, we have an exponential growth model.

- When 0 < b < 1, we have an exponential decay model.

Example: Using Exponential Regression to Fit a Model to Data

In 2007, a university study was published investigating the crash risk of alcohol impaired driving. Data from 2,871 crashes were used to measure the association of a person’s blood alcohol level (BAC) with the risk of being in an accident. The table below shows results from the study.[1] The relative risk is a measure of how many times more likely a person is to crash. So, for example, a person with a BAC of 0.09 is 3.54 times as likely to crash as a person who has not been drinking alcohol.

| BAC | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Relative Risk of Crashing | 1 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.38 | 2.09 | 3.54 |

| BAC | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| Relative Risk of Crashing | 6.41 | 12.6 | 22.1 | 39.05 | 65.32 | 99.78 |

- Let x represent the BAC level and let y represent the corresponding relative risk. Use exponential regression to fit a model to these data.

- After 6 drinks, a person weighing 160 pounds will have a BAC of about 0.16. How many times more likely is a person with this weight to crash if they drive after having a 6-pack of beer? Round to the nearest hundredth.

Try It

The table below shows a recent graduate’s credit card balance each month after graduation.

| Month | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Debt ($) | 620.00 | 761.88 | 899.80 | 1039.93 | 1270.63 | 1589.04 | 1851.31 | 2154.92 |

- Use exponential regression to fit a model to these data.

- If spending continues at this rate, what will the graduate’s credit card debt be one year after graduating?

Q & A

Is it reasonable to assume that an exponential regression model will represent a situation indefinitely?

No. Remember that models are formed by real-world data gathered for regression. It is usually reasonable to make estimates within the interval of original observation (interpolation). However, when a model is used to make predictions, it is important to use reasoning skills to determine whether the model makes sense for inputs far beyond the original observation interval (extrapolation).

Key Equations

| Half-life formula | If [latex]\text{ }A={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}[/latex], k < 0, the half-life is [latex]t=-\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(2\right)}{k}[/latex]. |

| Carbon-14 dating | [latex]t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(\frac{A}{{A}_{0}}\right)}{-0.000121}[/latex].[latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is the amount of carbon-14 when the plant or animal died

A is the amount of carbon-14 remaining today. t is that age of the fossil. |

| Doubling time formula | If [latex]A={A}_{0}{e}^{kt}[/latex], k > 0, the doubling time is [latex]t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}2}{k}[/latex] |

| Compound interest formula | [latex]\begin{array}{l}A\left(t\right)=P{\left(1+\frac{r}{n}\right)}^{nt} ,\text{ where}\hfill \\ A\left(t\right)\text{ is the account value at time }t\hfill \\ t\text{ is the number of years}\hfill \\ P\text{ is the initial investment, often called the principal}\hfill \\ r\text{ is the annual percentage rate (APR), or nominal rate}\hfill \\ n\text{ is the number of compounding periods in one year}\hfill \end{array}[/latex] |

Key Concepts

- The basic exponential function is [latex]f\left(x\right)=a{b}^{x}[/latex]. If b > 1, we have exponential growth; if 0 < b < 1, we have exponential decay.

- We can also write [latex]f\left(x\right)=a{b}^{x}[/latex] in terms of continuous growth as [latex]A={A}_{0}{e}^{kx}[/latex], where [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is the starting value. If [latex]{A}_{0}[/latex] is positive, then we have exponential growth when k > 0 and exponential decay when k < 0.

- In general, we solve problems involving exponential growth or decay in two steps. First, we set up a model and use the model to find the parameters. Then we use the formula with these parameters to predict growth and decay.

- We can find the age, t, of an organic artifact by measuring the amount, k, of carbon-14 remaining in the artifact and using the formula [latex]t=\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(k\right)}{-0.000121}[/latex] to solve for t.

- Given a substance’s doubling time or half-life, we can find a function that represents its exponential growth or decay.

- The value of an account at any time t can be calculated using the compound interest formula when the principal, annual interest rate, and compounding periods are known.

- The initial investment of an account can be found using the compound interest formula when the value of the account, annual interest rate, compounding periods, and life span of the account are known.

- We can use real-world data gathered over time to observe trends. Knowledge of linear, exponential, logarithmic, and logistic graphs help us to develop models that best fit our data.

- Any exponential function of the form [latex]y=a{b}^{x}[/latex] can be rewritten as an equivalent exponential function of the form [latex]y={A}_{0}{e}^{kx}[/latex] where [latex]k=\mathrm{ln}b[/latex].

- Exponential regression is used to model situations where growth begins slowly and then accelerates rapidly without bound or where decay begins rapidly and then slows down to get closer and closer to zero.

Glossary

- annual percentage rate (APR)

- the yearly interest rate earned by an investment account, also called nominal rate

- compound interest

- interest earned on the total balance, not just the principal

- doubling time

- the time it takes for a quantity to double

- half-life

- the length of time it takes for a substance to exponentially decay to half of its original quantity

- exponential growth

- a model that grows by a rate proportional to the amount present

- nominal rate

- the yearly interest rate earned by an investment account, also called annual percentage rate

- order of magnitude

- the power of ten when a number is expressed in scientific notation with one non-zero digit to the left of the decimal

Candela Citations

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Precalculus. Authored by: Abramson, Jay et al. . Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/fd53eae1-fa23-47c7-bb1b-972349835c3c@5.175. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download For Free at : http://cnx.org/contents/fd53eae1-fa23-47c7-bb1b-972349835c3c@5.175.

- College Algebra. Authored by: Abramson, Jay et al.. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/9b08c294-057f-4201-9f48-5d6ad992740d@5.2. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9b08c294-057f-4201-9f48-5d6ad992740d@5.2

- Question ID 29686. Authored by: McClure, Caren. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: IMathAS Community License CC-BY + GPL

- Question ID 100026. Authored by: Rieman, Rick. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: IMathAS Community License CC-BY + GPL

- Question ID 5801. Authored by: David Lippman. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: IMathAS Community License CC-BY + GPL

- Source: Indiana University Center for Studies of Law in Action, 2007 ↵