The early Romantic composer Robert Schumann was, like Schubert, a prolific composer of art songs. Also like Schubert, his life was tragically cut short, though unlike the younger composer, Robert enjoyed a good deal more success and recognition. This short introduction is a good summary of the composer’s career. If you’d like to know more, I’d certainly encourage you to read the rest of the article here. The article includes links to additional pieces not on our listening exam. It also tells the story of Robert and Clara Schumann, which is one of the great love stories of music history. Clara Schumann was as formidable a musician as her husband, and as a performer (concert pianist), she was quite famous. She and her husband were both very influential in the life of one of the other composers we will study in this period: Johannes Brahms.

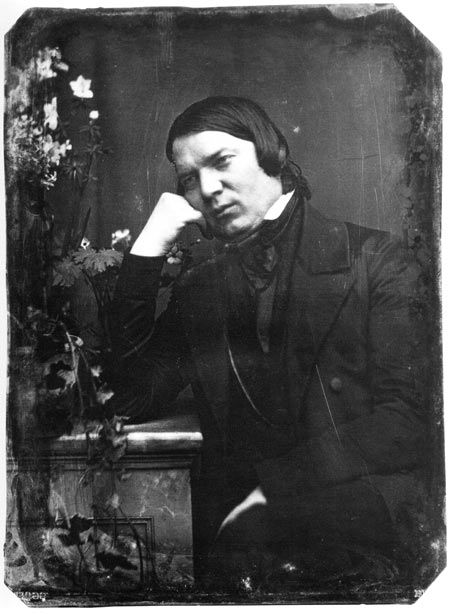

Robert Schumann (8 June 1810–29 July 1856) was a German composer and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career as a virtuoso pianist. He had been assured by his teacher Friedrich Wieck that he could become the finest pianist in Europe, but a hand injury ended this dream. Schumann then focused his musical energies on composing.

Schumann’s published compositions were written exclusively for the piano until 1840; he later composed works for piano and orchestra; manyLieder (songs for voice and piano); four symphonies; an opera; and other orchestral, choral, and chamber works. Works such as Kinderszenen,Album für die Jugend, Blumenstück, the Sonatas and Albumblätter are among his most famous. His writings about music appeared mostly in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Journal for Music), a Leipzig-based publication which he jointly founded.

In 1840, against the wishes of her father, Schumann married Friedrich Wieck’s daughter Clara, following a long and acrimonious legal battle, which found in favor of Clara and Robert. Clara also composed music and had a considerable concert career as a pianist, the earnings from which formed a substantial part of her father’s fortune.

Schumann suffered from a lifelong mental disorder, first manifesting itself in 1833 as a severe melancholic depressive episode, which recurred several times alternating with phases of ‘exaltation’ and increasingly also delusional ideas of being poisoned or threatened with metallic items. After a suicide attempt in 1854, Schumann was admitted to a mental asylum, at his own request, in Endenich near Bonn. Diagnosed with “psychotic melancholia”, Schumann died two years later in 1856 without having recovered from his mental illness.

Candela Citations

- Authored by: Elliott Jones. Provided by: Santa Ana College. Located at: http://www.sac.edu. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Robert Schumann. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Schumann. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike