While musicologists and music historians delve into details that are often too obscure for the purposes of our class, it’s worth reviewing this information on Beethoven’s 5th symphony.

Form

A typical performance usually lasts around 30–40 minutes. The work is in four movements:

First Movement: Allegro con brio

Listen: First Movement

Please listen to the first movement performed by the Fulda Symphony

The first movement opens with the four-note motif discussed above, one of the most famous in Western music. There is considerable debate among conductors as to the manner of playing the four opening bars. Some conductors take it in strict allegrotempo; others take the liberty of a weighty treatment, playing the motif in a much slower and more stately tempo; yet others take the motif molto ritardando (a pronounced slowing through each four-note phrase), arguing that the fermata over the fourth note justifies this. Some critics and musicians consider it crucial to convey the spirit of [pause]and-two-and one, as written, and consider the more common one-two-three-four to be misleading. To wit:

About the “ta-ta-ta-Taaa”: Beethoven begins with eight notes. They rhyme, four plus four, and each group of four consists of three quick notes plus one that is lower and much longer (in fact unmeasured). The space between the two rhyming groups is minimal, about one-seventh of a second if we go by Beethoven’s metronome mark; moreover, Beethoven clarifies the shape by lengthening the second of the long notes. This lengthening, which was an afterthought, is tantamount to writing a stronger punctuation mark. As the music progresses, we can hear in the melody of the second theme, for example (or later, in the pairs of antiphonal chords of woodwinds and strings), that the constantly invoked connection between the two four-note units is crucial to the movement. … The source of Beethoven’s unparalleled energy here is in his writing long sentences and broad paragraphs whose surfaces are articulated with exciting activity. Indeed, we discover soon enough that the double “ta-ta-ta-Taaa” is an open-ended beginning, not a closed and self-sufficient unit (Misunderstanding of this opening was nurtured by a nineteenth-century performance tradition in which the first five measures were read as a slow, portentous exordium, the main tempo being attacked only after the second hold.) What makes this opening so dramatic is the violence of the contrast between the urgency in the eighth notes and the ominous freezing of motion in the unmeasured long notes. The music starts with a wild outburst of energy but immediately crashes into a wall. Seconds later, Beethoven jolts us with another such sudden halt. The music draws up to a half-cadence on a G-major chord, short and crisp in the whole orchestra, except for the first violins, who hang on to their high C for an unmeasured length of time. Forward motion resumes with a relentless pounding of eighth notes.

The first movement is in the traditional sonata form that Beethoven inherited from his classical predecessors, Haydn and Mozart (in which the main ideas that are introduced in the first few pages undergo elaborate development through many keys, with a dramatic return to the opening section—the recapitulation—about three-quarters of the way through). It starts out with two dramatic fortissimo phrases, the famous motif, commanding the listener’s attention. Following the first four bars, Beethoven uses imitations and sequences to expand the theme, these pithy imitations tumbling over each other with such rhythmic regularity that they appear to form a single, flowing melody. Shortly after, a very short fortissimo bridge, played by the horns, takes place before a second theme is introduced. This second theme is in E♭ major, the relative major, and it is more lyrical, written piano and featuring the four-note motif in the string accompaniment. The codetta is again based on the four-note motif. The development section follows, including the bridge. During the recapitulation, there is a brief solo passage for oboe in quasi-improvisatory style, and the movement ends with a massive coda.

Second Movement: Andante con moto

Listen: Second Movement

Please listen to the second movement performed by the Fulda Symphony

The second movement, in A♭ major, is a lyrical work in double variation form, which means that two themes are presented and varied in alternation. Following the variations there is a long coda.

The movement opens with an announcement of its theme, a melody in unison by violas and cellos, with accompaniment by the double basses. A second theme soon follows, with a harmony provided by clarinets, bassoons, and violins, with a triplet arpeggio in the violas and bass. A variation of the first theme reasserts itself. This is followed up by a third theme, thirty-second notes in the violas and cellos with a counterphrase running in the flute, oboe, and bassoon. Following an interlude, the whole orchestra participates in a fortissimo, leading to a series of crescendos and a coda to close the movement.

Third Movement: Scherzo. Allegro

Listen: Third Movement

Please listen to the third movement performed by the Fulda Symphony

The third movement is in ternary form, consisting of a scherzo and trio. It follows the traditional mold of Classical-era symphonic third movements, containing in sequence the main scherzo, a contrasting trio section, a return of the scherzo, and a coda. However, while the usual Classical symphonies employed a minuet and trio as their third movement, Beethoven chose to use the newer scherzo and trio form.

Listen: Theme

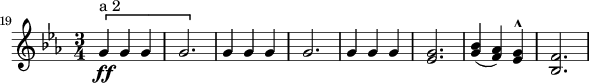

The movement returns to the opening key of C minor and begins with the following theme, played by the cellos and double basses:

The opening theme is answered by a contrasting theme played by the winds, and this sequence is repeated. Then the horns loudly announce the main theme of the movement, and the music proceeds from there.

The trio section is in C major and is written in a contrapuntal texture. When the scherzo returns for the final time, it is performed by the strings pizzicato and very quietly.

“The scherzo offers contrasts that are somewhat similar to those of the slow movement in that they derive from extreme difference in character between scherzo and trio. . . . The Scherzo then contrasts this figure with the famous ‘motto’ (3 + 1) from the first movement, which gradually takes command of the whole movement.”

The third movement is also notable for its transition to the fourth movement, widely considered one of the greatest musical transitions of all time.

Fourth Movement: Allegro

Listen: Fourth Movement

Please listen to the fourth movement performed by the Fulda Symphony

The fourth movement begins without pause from the transition. The music resounds in C major, an unusual choice by the composer as a symphony that begins in C minor is expected to finish in that key. In Beethoven’s words:

Many assert that every minor piece must end in the minor. Nego! . . . Joy follows sorrow, sunshine—rain.

The triumphant and exhilarating finale is written in an unusual variant of sonata form: at the end of the development section, the music halts on a dominant cadence, played fortissimo, and the music continues after a pause with a quiet reprise of the “horn theme” of the scherzo movement. The recapitulation is then introduced by a crescendo coming out of the last bars of the interpolated scherzo section, just as the same music was introduced at the opening of the movement. The interruption of the finale with material from the third “dance” movement was pioneered by Haydn, who had done the same in his Symphony No. 46 in B, from 1772. It is not known whether Beethoven was familiar with this work.

The Fifth Symphony finale includes a very long coda, in which the main themes of the movement are played in temporally compressed form. Towards the end the tempo is increased topresto. The symphony ends with 29 bars of C major chords, played fortissimo. In The Classical Style, Charles Rosen suggests that this ending reflects Beethoven’s sense of Classical proportions: the “unbelievably long” pure C major cadence is needed “to ground the extreme tension of [this] immense work.”

It was shown recently that this long chord sequence was a pattern that Beethoven borrowed from the Italian composer Luigi Cherubini, whom Beethoven “esteemed the most” among his contemporary musicians. Spending much of his life in France, Cherubini employed this pattern consistently to close his overtures, which Beethoven knew well. The ending of his famous symphony repeats almost note by note and pause by pause the conclusion of Cherubini’s overture to his opera Eliza, composed in 1794 and presented in Vienna in 1803.

Fate Motif

The initial motif of the symphony has sometimes been credited with symbolic significance as a representation of Fate knocking at the door. This idea comes from Beethoven’s secretary and factotum Anton Schindler, who wrote, many years after Beethoven’s death:

The composer himself provided the key to these depths when one day, in this author’s presence, he pointed to the beginning of the first movement and expressed in these words the fundamental idea of his work: “Thus Fate knocks at the door!”

Schindler’s testimony concerning any point of Beethoven’s life is disparaged by experts (he is believed to have forged entries in Beethoven’s conversation books). Moreover, it is often commented that Schindler offered a highly romanticized view of the composer.

There is another tale concerning the same motif; the version given here is from Antony Hopkins’ description of the symphony. Carl Czerny (Beethoven’s pupil, who premiered the “Emperor” Concerto in Vienna) claimed that “the little pattern of notes had come to [Beethoven] from a yellow-hammer’s song, heard as he walked in the Prater-park in Vienna.” Hopkins further remarks that “given the choice between a yellow-hammer and Fate-at-the-door, the public has preferred the more dramatic myth, though Czerny’s account is too unlikely to have been invented.”

In his Omnibus television lecture series in 1954, Leonard Bernstein has likened the Fate Motif to the four note coda common to classical symphonies. These notes would terminate the classical symphony as a musical coda, but for Beethoven they become a motif repeating throughout the work for a very different and dramatic effect, he says.

Evaluations of these interpretations tend to be skeptical. “The popular legend that Beethoven intended this grand exordium of the symphony to suggest ‘Fate Knocking at the gate’ is apocryphal; Beethoven’s pupil, Ferdinand Ries, was really author of this would-be poetic exegesis, which Beethoven received very sarcastically when Ries imparted it to him.” Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner remarks that “Beethoven had been known to say nearly anything to relieve himself of questioning pests”; this might be taken to impugn both tales.

Repetition of the Opening Motif

It is commonly asserted that the opening four-note rhythmic motif (short-short-short-long; see above) is repeated throughout the symphony, unifying it. “It is a rhythmic pattern (dit-dit-dit-dot*) that makes its appearance in each of the other three movements and thus contributes to the overall unity of the symphony” (Doug Briscoe); “a single motif that unifies the entire work” (Peter Gutmann); “the key motif of the entire symphony”; “the rhythm of the famous opening figure . . . recurs at crucial points in later movements” (Richard Bratby). The New Grove encyclopedia cautiously endorses this view, reporting that “[t]he famous opening motif is to be heard in almost every bar of the first movement—and, allowing for modifications, in the other movements.”

There are several passages in the symphony that have led to this view. For instance, in the third movement the horns play the following solo in which the short-short-short-long pattern occurs repeatedly:

In the second movement (at measure 76), an accompanying line plays a similar rhythm:

In the finale, Doug Briscoe (cited above) suggests that the motif may be heard in the piccolo part, presumably meaning the following passage:

Later, in the coda of the finale, the bass instruments repeatedly play the following:

On the other hand, some commentators are unimpressed with these resemblances and consider them to be accidental. Antony Hopkins, discussing the theme in the scherzo, says “no musician with an ounce of feeling could confuse [the two rhythms],” explaining that the scherzo rhythm begins on a strong musical beat whereas the first-movement theme begins on a weak one. Donald Francis Tovey pours scorn on the idea that a rhythmic motif unifies the symphony: “This profound discovery was supposed to reveal an unsuspected unity in the work, but it does not seem to have been carried far enough.” Applied consistently, he continues, the same approach would lead to the conclusion that many other works by Beethoven are also “unified” with this symphony, as the motif appears in the “Appassionata” piano sonata, the Fourth Piano Concerto, and in the String Quartet, Op. 74. Tovey concludes, “the simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at this stage of his art.”

To Tovey’s objection can be added the prominence of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure in earlier works by Beethoven’s older Classical contemporaries Haydn and Mozart. To give just two examples, it is found in Haydn’s “Miracle” Symphony, No. 96) and in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503. Such examples show that “short-short-short-long” rhythms were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven’s day.

It seems likely that whether or not Beethoven deliberately, or unconsciously, wove a single rhythmic motif through the Fifth Symphony will (in Hopkins’s words) “remain eternally open to debate.”

Candela Citations

- Authored by: Elliott Jones. Provided by: Santa Ana College. Located at: http://www.sac.edu. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Symphony No. 5 (Beethoven). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_No._5_(Beethoven)#Form. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike