https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=711&action=edit

Expressionism , like impressionism, originated in the visual arts and was then applied to other arts including music. Expressionism can be considered a reaction to the ethereal sweetness of impressionism. Instead of impressions of natural beauty, expressionism looks inward to the angst and fear lurking in the subconscious mind.

In music, expressionism is manifest in the full embrace of jarring dissonance. Initially expressionism was a modernist movement, in poetry and painting, originating in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century as an avant-garde style before the First World War. Expressionist artists sought to express meaning or emotional experience rather than physical reality. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it radically for emotional effect in order to evoke moods or ideas. The style extended to a wide range of the arts, including expressionist architecture, painting, literature, theatre, dance, film and music.

As mentioned above, the term is sometimes suggestive of angst. In a general sense, painters such as Matthias Grünewald and El Greco are sometimes termed expressionist, though in practice the term is applied mainly to 20th-century works. The Expressionist emphasis on individual perspective has been characterized as a reaction to positivism and other artistic styles such as Naturalism and Impressionism.

| The Scream | |

|---|---|

|

|

Dillon- Can you delete the 6 boxes in the above image?

The Scream (Norwegian: Skrik) is the popular name given to each of four versions of a composition, created as both paintings and pastels, by Norwegian Expressionist artist Edvard Munch between 1893 and 1910. The German title Munch gave these works is Der Schrei der Natur (The Scream of Nature). The works show a figure with an agonized expression against a landscape with a tumultuous orange sky. Arthur Lubow has described The Scream as “an icon of modern art, a Mona Lisa for our time.

Music

The term expressionism “was probably first applied to music in 1918, especially to Schoenberg,” because like the painter Kandinsky he avoided “traditional forms of beauty” to convey powerful feelings in his music. Schoenberg was also an Expressionist painter). Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg,were the members of the Second Viennese School. Other composers that have been associated with Expressionism are Krenek (the Second Symphony), Paul Hindemith (The Young Maiden), Igor Stravinsky (Japanese Songs), Alexander Scriabin (late piano sonatas) (Adorno 2009, 275). Another significant expressionist was Béla Bartók in early works, written in the second decade of the 20th-century, such as Bluebeard’s Castle (1911), The Wooden Prince (1917), and The Miraculous Mandarin (1919). Important precursors of expressionism are Richard Wagner (1813–83), Gustav Mahler (1860–1911), and Richard Strauss (1864–1949).

Theodor Adorno describes expressionism in music as concerned with the unconscious, and states that “the depiction of fear lies at the centre” , with dissonance predominating, so that the “harmonious, affirmative element of art is banished.” Erwartung and Die Glückliche Hand, by Schoenberg, and Wozzeck, an opera by Alban Berg (based on the play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner), are examples of Expressionist works. If one were to draw an analogy from paintings, one may describe the expressionist painting technique as the distortion of reality (mostly colors and shapes) to create a nightmarish effect for the particular painting as a whole. Expressionist music roughly does the same thing, where the dramatically increased dissonance creates, aurally, a nightmarish atmosphere.

Go to this link and read in more detail (also click on more…) about the story of this opera: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b8WeX8MrThU. As you listen, Does it seem logical that this style composition fits the drama of this opera.?

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=712&action=edit

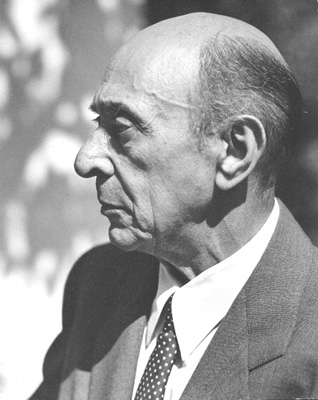

Arnold Schoenberg

As one of the most influential composers of the twentieth century, Arnold Schoenberg championed atonality in music composition, first through freely composed, expressionist works such as Pierrot Lunaire (one song from that cycle, “Madonna,” is on our playlist), and later through his own system of composition commonly referred to as as twelve-tone music (the Piano Suite, a portion of which is on our list, was composed using this method). This system of atonal composition became the dominant musical idiom at music conservatories in America and Europe during the latter half of the twentieth century. Though the influence of twelve-tone composition appears to be waning, its impact on the music of the last century is enormous. Love it or hate it, the music of Schoenberg walks large on the stage of history.

Early Life

In his twenties, Schoenberg earned a living by orchestrating operettas, while composing his own works, such as the string sextet Verklärte Nacht (“Transfigured Night”). He later made an orchestral version of this, which became one of his most popular pieces. Both Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler recognized Schoenberg’s significance as a composer; Strauss when he encountered Schoenberg’s Gurre-Lieder, and Mahler after hearing several of Schoenberg’s early works.

Schoenberg influenced Strauss and Mahler Strauss turned to a more conservative idiom in his own work after 1909, and at that point dismissed Schoenberg. Mahler adopted him as a protégé and continued to support him, even after Schoenberg’s style reached a point Mahler could no longer understand. Mahler worried about who would look after him after his death. Schoenberg, who had initially despised and mocked Mahler’s music, was converted by the “thunderbolt” of Mahler’s Third Symphony, which he considered a work of genius. Afterward he “spoke of Mahler as a saint.”

One of his most important works from this atonal or pantonal period is the highly influential Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, of 1912, a novel cycle of expressionist songs set to a German translation of poems by the Belgian-French poet Albert Giraud. Utilizing the technique of Sprechstimme, or melodramatically spoken recitation, the work pairs a female vocalist with a small ensemble of five musicians. The ensemble, which is now commonly referred to as the Pierrot ensemble, consists of flute (doubling on piccolo), clarinet (doubling on bass clarinet), violin (doubling on viola), violoncello, speaker, and piano.

World War I

World War I brought a crisis in his development. Military service disrupted his life when at the age of 42 he was in the army. He was never able to work uninterrupted or over a period of time, and as a result he left many unfinished works and undeveloped “beginnings”. On one occasion, a superior officer demanded to know if he was “this notorious Schoenberg, then”; Schoenberg replied: “Beg to report, sir, yes. Nobody wanted to be, someone had to be, so I let it be me” (according to Norman Lebrecht (2001), this is a reference to Schoenberg’s apparent “destiny” as the “Emancipator of Dissonance”).

In what Ross calls an “act of war psychosis,” Schoenberg drew comparisons between Germany’s assault on France and his assault on decadent bourgeois artistic values. In August 1914, while denouncing the music of Bizet, Stravinsky andRavel, he wrote: “Now comes the reckoning! Now we will throw these mediocre kitschmongers into slavery, and teach them to venerate the German spirit and to worship the German God.”

Development of the Twelve-Tone Method

Later, Schoenberg was to develop the most influential version of the dodecaphonic (also known as twelve-tone) method of composition, which in French and English was given the alternative name serialism by René Leibowitzand Humphrey Searle in 1947. This technique was taken up by many of his students, who constituted the so-called Second Viennese School. They included Anton Webern, Alban Berg and Hanns Eisler, all of whom were profoundly influenced by Schoenberg. He published a number of books, ranging from his famous Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony) to Fundamentals of Musical Composition, many of which are still in print and used by musicians and developing composers.

Along with his twelve-tone works, 1930 marks Schoenberg’s return to tonality, with numbers 4 and 6 of the Six Pieces for Male Chorus Op.35, the other pieces being dodecaphonic.

Third Reich and Move to America

Schoenberg continued in his post until the Nazis came to power under Adolf Hitler in 1933. While vacationing in France, he was warned that returning to Germany would be dangerous. Schoenberg formally reclaimed membership in the Jewish religion at a Paris synagogue, then traveled with his family to the United States.

His first teaching position in the United States was in Boston. He moved to Los Angeles, where he taught at the University of Southern California and the University of California. He lived directly across the street from Shirley Temple’s house, and there he befriended fellow composer (and tennis partner) George Gershwin. The Schoenbergs began holding Sunday afternoon gatherings that were known for excellent coffee and Viennese pastries. Frequent guests included Otto Klemperer (who studied composition privately with Schoenberg beginning in April 1936), Edgard Varèse, Joseph Achron, Louis Gruenberg, Ernst Toch, and, on occasion, well-known actors such as Harpo Marx and Peter Lorre. Composers Leonard Rosenman and George Tremblay studied with Schoenberg at this time.

During this final period, he composed several notable works, including the difficult Violin Concerto, Op. 36 (1934/36), the Kol Nidre, Op. 39, for chorus and orchestra (1938), the Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte, Op. 41 (1942), the haunting Piano Concerto, Op. 42 (1942), and his memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, A Survivor from Warsaw, Op. 46 (1947). During this period his notable students included John Cage and Lou Harrison.

Music

Listen: Second String Quartet

Please listen to the following audio file to hear the fourth movement played by the Carmel Quartet with soprano Rona Israel-Kolatt, in 2007. This work is from Schoenberg’s first period)

Schoenberg’s Three periods

Schoenberg’s significant compositions in the repertory of modern art music extend over a period of more than 50 years. Traditionally they are divided into three periods though this division is arguably arbitrary as the music in each of these periods is considerably varied. The first of these periods, 1894–1907, is identified in the legacy of the high-Romantic composers of the late nineteenth century, as well as with “expressionist” movements in poetry and art. The second, 1908–1922, is typified by the abandonment of key centers, a move often described (though not by Schoenberg) as “free atonality.” The third, from 1923 onward, commences with Schoenberg’s invention of dodecaphonic, or “twelve-tone” compositional method. Schoenberg’s best-known students, Hanns Eisler, Alban Berg, andAnton Webern, followed Schoenberg faithfully through each of these intellectual and aesthetic transitions, though not without considerable experimentation and variety of approach.

First Period: Late Romanticism

Schoenberg’s concerns as a composer positioned him uniquely among his peers, in that his procedures exhibited characteristics of both Brahms and Wagner. Schoenberg’s Six Songs, Op. 3 (1899–1903), for example, exhibit a conservative clarity of tonal organization typical of Brahms and Mahler, reflecting an interest in balanced phrases and an undisturbed hierarchy of key relationships. However, the songs also explore unusually bold incidental chromaticism, and seem to aspire to a Wagnerian “representational” approach to motivic identity. The synthesis of these approaches reaches an apex in his Verklärte Nacht, Op. 4 (1899), a programmatic work for string sextet that develops several distinctive “leitmotif”-like themes, each one eclipsing and subordinating the last.

Second Period: Free Atonality

Schoenberg’s music from 1908 onward experiments in a variety of ways with the absence of traditional keys or tonal centers. His first explicitly atonal piece was the second string quartet, Op. 10, with soprano. The last movement of this piece has no key signature, marking Schoenberg’s formal divorce from diatonic harmonies. Other important works of the era include his song cycle Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten, Op. 15 (1908–1909), his Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16 (1909), the influential Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21 (1912), as well as his dramatic Erwartung, Op. 17 (1909).

Third Period: Twelve-Tone and Tonal Works

In the early 1920s, he worked at evolving a means of order that would make his musical texture simpler and clearer. This resulted in the “method of composing with twelve tones which are related only with one another,” in which the twelve pitches of the octave (unrealized compositionally) are regarded as equal, and no one note or tonality is given the emphasis it occupied in classical harmony. He regarded it as the equivalent in music of Albert Einstein’s discoveries in physics. Schoenberg announced it characteristically, during a walk with his friend Josef Rufer, when he said, “I have made a discovery which will ensure the supremacy of German music for the next hundred years.” This period included the Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 (1928); Piano Pieces, Opp. 33a & b (1931), and the Piano Concerto, Op. 42 (1942). Contrary to his reputation for strictness, Schoenberg’s use of the technique varied widely according to the demands of each individual composition. Thus the structure of his unfinished opera Moses und Aron is unlike that of his Fantasy for Violin and Piano, Op. 47 (1949).

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=713&action=edit

Pierrot Lunaire (from Shoenberg’s second period)

Pierrot Lunaire is a song cycle written in three parts with each part containing seven songs. It was composed during Schoenberg’s second period after the composer had turned to atonality but before he developed his twelve-tone method. The inward psychological focus of the text and the eerie combination of atonality and sprechstimme mark this as a clearly expressionist work. Sprechstimme is an expressionist technique in which the singer performs the musical line in a half-sung, half-spoken style. The written notes on the page are used as a guide but are only approximated by the singer.

The narrator (voice-type unspecified in the score, but traditionally performed by a soprano) delivers the poems in the Sprechstimme style. The work is atonal but does not use the twelve-tone technique that Schoenberg would devise eight years later.

The work originated in a commission by Zehme for a cycle for voice and piano, setting a series of poems by the Belgian writer Albert Giraud. The verses had been first published in 1884, and later translated into German by Otto Erich Hartleben. It was performed for the first time in the western hemisphere at the Klaw Theatre in New York City on February 4, 1923, with George Gershwin and Carl Ruggles in attendance.

Synopsis

Please go to this Synopsis and read only the Synopsis at this location. It will give you an idea of the bazaar nature of the poem and the symbolist movement which represents.

Music: A variety of classical forms and techniques, including canon, fugue, rondo, passacaglia and free counterpoint are used. The poetry is a German version of a rondeau of the old French type with a double refrain.

The instrumental combinations (including doublings) vary between most movements. The entire ensemble plays together only in the 11th, 14th and final 4 settings.

The atonal, expressionistic settings of the text, with their echoes of German cabaret, bring the poems vividly to life. Sprechstimme literally “speech-singing” in German, is a style in which the vocalist uses the specified rhythms and pitches, but does not sustain the pitches, allowing them to drop or rise, in the manner of speech.

Expressionist Music – Traits

Expressionism is a modernist movement that began in Germany and Austria in the early twentieth century. Schoenberg, Austrian in descent, was associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art. Being from Austria at this time, his music was often labeled as degenerate music since Schoenberg is Jewish. Expressionistic music is dominated by dissonance rather than consonance, and can create an “unsettling” feeling among its listeners For many, expressionistic music meant a rejection of the past and an acceptance of the innovative, unfamiliar future. The text of “Nacht” can be described as ominous, and depicts the wings of black moths covering the sun. These views are characteristic of expressionistic poetry.

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=714&action=edit

History – Pierrot Lunaire

In the foreword to Pierrot Lunaire (1912), Schoenberg explains how his Sprechstimme should be achieved. He explains that the indicated rhythms should be adhered to, but that whereas in ordinary singing a constant pitch is maintained through a note, here the singer “immediately abandons it by falling or rising. The goal is certainly not at all a realistic, natural speech. On the contrary, the difference between ordinary speech and speech that collaborates in a musical form must be made plain. But it should not call singing to mind, either.”

The earliest compositional use of Sprechtimme was in the first version of Engelbert Humperdinck’s 1897 melodrama Königskinder where it may have been intended to imitate a style already in use by singers of lieder and popular song, but it is more closely associated with the composers of the Second Viennese School. Arnold Schoenberg asks for the technique in a number of pieces, but it was Pierrot Lunaire (1912) where he used sprechstimme throughout and left a note attempting to explain the technique. Alban Berg adopted the technique and asked for it in parts of his operas Wozzeck and Lulu.

Schoenberg would later use a notation without a traditional clef in the Ode to Napoleon Bonaparte (1942), A Survivor from Warsaw (1947) and his unfinished opera Moses und Aron, which eliminated any reference to a specific pitch, but retained the relative slides and articulations.

*************************************

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=715&action=edit

Twelve-tone technique

Twelve tone technique is also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition – a method of musical composition devised by Arnold Schoenberg ensures that all 12 notes of the chromatic scale are sounded as often as one another in a piece of music while preventing the emphasis of any one note. This is accomplished through the use of tone rows – orderings of the 12 pitch classes. All 12 notes are thus given more or less equal importance, and the music avoids being centered in a tonality (key). The technique was influential on composers in the mid-20th century. It is commonly considered a form of serialism.

Schoenberg’s countryman and contemporary Josef Matthias Hauer also developed a similar system using unordered hexachords or tropes—but with no connection to Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique. Other composers have created systematic use of the chromatic scale, but Schoenberg’s method is considered to be historically and aesthetically most significant.

Tone Row

Listen: “Sehr langsam”

Please listen to the following audio file to hear a sample of “Sehr langsam” from String Trio Op. 20 by Anton Webern, an example of the twelve-tone technique, a type of serialism.

The basis of the twelve-tone technique is the tone row, an ordered arrangement of the twelve notes of the chromatic scale (the twelve equal tempered pitch classes). Stated simply The row is a specific ordering of all twelve notes of the chromatic scale and no note is repeated within the row.

These rows may be manipulated using many a number of systems such as retrograde , and inversion etc. Examples are below:

Example

Suppose the prime form of the row is as follows:

The retrograde (starting with the last note and going backwards.) – see above example) the is the prime form in reverse order:

The inversion is the prime form with the intervals inverted (so that a rising interval third becomes a falling interval):

![]()

And the retrograde inversion is the inverted row in retrograde:(the above example in reverse)

A simple case is the ascending chromatic scale, the retrograde inversion of which is identical to the prime form, and the retrograde of which is identical to the inversion (thus, only 24 forms of this tone row are available).

Figure 2. Prime, retrograde, inverted, and retrograde-inverted forms of the ascending chromatic scale. P and RI are the same (to within transposition), as are R and I.

In the above example, as is typical, the retrograde inversion contains three points where the sequence of two pitches are identical to the prime row. Thus the generative power of even the most basic transformations is both unpredictable and inevitable. Motivic development can be driven by such internal consistency.

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=716&action=edit

Here is some additional information on Schoenberg’s Suite for Piano. Our playlist features the Trio, which is a portion of movement 5. Please note that this suite was the first piece composed entirely in Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique. It’s also worth noting the connection via genre to the suites we studied in the Baroque era.

Arnold Schoenberg’s Suite for Piano (German: Suite für Klavier), Op. 25, is a twelve tone piece for piano composed between 1921 and 1923.

The work is the earliest in which Schoenberg employs a row of “12 tones related only to one another” in every movement: the earlier 5 Stücke, Op. 23 (1920–23) employs a 12-tone row only in the final Waltz movement, and the Serenade, Op. 24 uses a single row in its central Sonnet.

The Basic Set of the Suite for Piano consists of the following succession: E–F–G–D♭–G♭–E♭–A♭–D–B–C–A–B♭.

In form and style the work echoes many features of the Baroque suite.

Schoenberg’s Suite has six movements:

- Präludium (0:00)

- Gavotte (1:07)

- Musette (2:28)

- Intermezzo (5:20)

- Menuett. Trio (9:09)

- Gigue (14:31)

A performance of the entire Suite für Klavier takes around 16 minutes.

Figure 1. Polyphonic complex of three tetrachords from early sketch for Schoenberg’s Suite for Piano, Op. 25 (Whittall 2008, p. 34). The bottom being the BACH motif in retrograde: HCAB.

In this work Schoenberg employs transpositions and inversions of the row for the first time: the sets employed are P-0, I-0, P-6, I-6 and their retrogrades. Arnold Whittall has suggested that “The choice of transpositions at the sixth semitone—the tritone—may seem the consequence of a desire to hint at ‘tonic-dominant’ relationships, and the occurrence of the tritone G-D♭ in all four sets is a hierarchical feature which Schoenberg exploits in several places.”

The Suite for Piano was first performed by Schoenberg’s pupil Eduard Steuermann in Vienna on 25 February 1924. Steuermann made a commercial recording of the work in 1957. The first recording of the Suite for Piano to be released was made by Niels Viggo Bentzon some time before 1950.

The Gavotte movement contains, “a parody of a baroque keyboard suite that involves the cryptogram of Bach’s name as an important harmonic and melodic device (Stuckenschmidt 1977, 108; Lewin 1982–83, n.9)” and a related quotation of Schoenberg’s op. 19/vi.