https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=706&action=edit

While late romantic period composers such as Strauss, Rachmaninoff, and Mahler continued into the 20th Century as a post-Romantic movement, another development at this time was impressionism. Impressionism was a movement in the visual arts, namely painting, centered in Paris in the late 19th century. The term was later applied, not always to the liking of the composers, to the music of early 20th century French composers who were turning away from the grandiosity of late Romantic orchestral music.

An example of Impressionistic art: The major composer associated with Impressionism in music is Debussy.

Link address: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impressionism#/media/File:Claude_Monet,_Impression,_soleil_levant.jpg

Impressionism is a 19th-century art movement that originated with a group of Paris-based artists whose independent exhibitions brought them to prominence during the 1870s and 1880s. Impressionist painting characteristics include relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience, and unusual visual angles.

The Impressionists faced harsh opposition from the conventional art community in France. The name of the style derives from the title of a Claude Monet work, Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise), which provoked the critic Louis Leroy to coin the term in a satirical review published in the Parisian newspaper Le Charivari.

The development of Impressionism in the visual arts was soon followed by analogous styles in other media that became known as impressionist music and impressionist literature.

Music and Literature

Originating in France, musical Impressionism is characterized by suggestion and atmosphere, and eschews the emotional excesses of the Romantic era. Impressionist composers favoured short forms such as the nocturne, arabesque, and prelude, and often explored uncommon scales such as the whole tone scale. Perhaps the most notable innovations of Impressionist composers were the introduction of major 7th chords and the extension of chord structures in 3rds to five- and six-part harmonies.

Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravelare generally considered the greatest Impressionist composers, but Debussy disavowed the term, calling it the invention of critics. Paul Dukas is another French composer sometimes considered an Impressionist, but his style is perhaps more closely aligned to the late Romanticists. Musical Impressionism beyond France includes the work of such composers as Ottorino Respighi (Italy) Ralph Vaughan Williams, John Ireland (England), Manuel De Falla, and Isaac Albeniz .

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=707&action=edit

Debussy’s music is noted for its sensory content and frequent usage of atonality. The prominent French literary style of his period was known as Symbolism, and this movement directly inspired Debussy both as a composer and as an active cultural participant.

Musical Development: Debussy was a child prodigy and difficult personality whose innovations are seen as the beginnings of modernism in music. in 1872, at age ten, he entered the Paris Conservatoire, where he studied wirth the prominent instructors and musicians of the 1870’s for the next 11 years.

Debussy was argumentative and experimental from the outset, although clearly talented. He challenged the rigid teaching of the Academy, favoring instead dissonances and intervals that were frowned upon. Like Georges Bizet, he was a brilliant pianist and an outstanding sight reader, who could have had a professional career had he so wished. The pieces he played in public at this time included sonata movements by Beethoven, Schumann and Weber, and Chopin’s Ballade No. 2, a movement from the Piano Concerto No. 1, and the Allegro de concert.

During the summers of 1880, 1881, and 1882, Debussy accompanied Nadezhda von Meck, the wealthy patroness of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, as she travelled with her family in Europe. The young composer’s many musical activities during these vacations included playing four-hand pieces with von Meck at the piano, giving music lessons to her children, and performing in private concerts with some of her musician friends. In September 1880 von Meck sent Debussy’s Danse bohémienne for Tchaikovsky’s perusal. A month later Tchaikovsky wrote back to her: “It is a very pretty piece, but it is much too short. Not a single idea is expressed fully, the form is terribly shriveled, and it lacks unity.” Debussy did not publish the piece, and the manuscript remained in the von Meck family; it was eventually sold to B. Schott’s Sohne in Mainz, and published by them in 1932.

As the winner of the 1884 Prix de Rome with his composition L’enfant prodigue, Debussy received a scholarship to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which included a four-year residence at the Villa Medici, the French Academy in Rome, to further his studies (1885–1887). According to letters to Marie-Blanche Vasnier, perhaps in part designed to gain her sympathy, he found the artistic atmosphere stifling, the company boorish, the food bad, and the monastic quarters “abominable.” Neither did he delight in Italian opera, as he found the operas of Donizetti and Verdi not to his taste. Debussy was often depressed and unable to compose, but he was inspired by Franz Liszt, whose command of the keyboard he found admirable. In June 1885, Debussy wrote of his desire to follow his own way, saying, “I am sure the Institute would not approve, for, naturally it regards the path which it ordains as the only right one. But there is no help for it! I am too enamored of my freedom, too fond of my own ideas!”

During his visits to Bayreuth in 1888–9, Debussy was exposed to Wagnerian opera, which would have a lasting impact on his work. Debussy, like many young musicians of the time, responded positively to Richard Wagner’s sensuousness, mastery of form, and striking harmonies. Wagner’s extroverted emotionalism was not to be Debussy’s way, but the German composer’s influence is evident in La damoiselle élue and the 1889 piece Cinq poèmes de Charles Baudelaire.

Around this time, Debussy met Erik Satie, who proved a kindred spirit in his experimental approach to composition and to naming his pieces. Both musicians were bohemians during this period, enjoying the same cafe society and struggling to stay afloat financially.

In 1889, at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, Debussy first heard Javanese gamelan music. He incorporated gamelan scales, melodies, rhythms, and ensemble textures into some of his compositions, most notably Pagodes from his piano collection Estampes.

Music Style

- occasional absence of tonality;

- use of parallel chords which do not represent functional harmony at all, but rather ‘chordal melodies’, enriched unisons,” described by some writers as non-functional harmonies;

- Bitonality ( two keys sounding at the same time)

- whole-tone and pentatonic scales;

- unusual shifts in modulations “without any harmonic bridge.”

Debussy’s achievement was the synthesis of a “melodic tonality” with harmonies, different from traditional “harmonic tonality.”

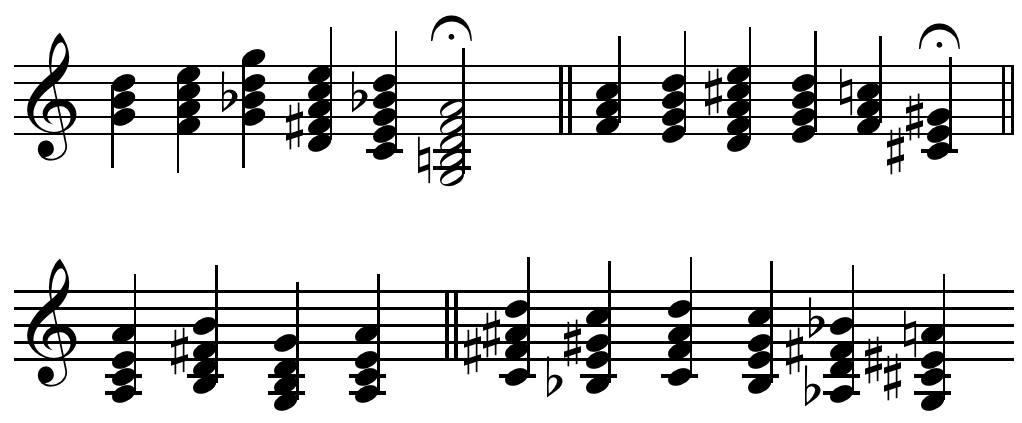

The application of the term “Impressionist” to Debussy and the music he influenced is a matter of intense debate within academic circles. One side argues that the term is a misnomer, an inappropriate label which Debussy himself opposed. Note the parallelism in the chords below especially in the second row.

Figure 3.Chords, featuring chromatically altered sevenths and ninths and progressing unconventionally, explored by Debussy in a “celebrated conversation at the piano with his teacher Ernest Guiraud”

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=708&action=edit

Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (L. 86), known in English as Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, is a symphonic poem for orchestra. It was first performed in Paris on December 22, 1894.

Below is a drawing of Frontispiece for “L’après-midi d’un faune”, by Édouard Manet.

Please wrap text

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%27apr%C3%A8s-midi_d%27un_faune_(poem)

Background

The composition was inspired by the poem L’après-midi d’un faune by Stéphane Mallarmé. Debussy’s work later provided the basis for the ballet Afternoon of a Faun, choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky. It is one of Debussy’s most famous works and is considered a turning point in the history of music; Pierre Boulez has said he considers the score to be the beginning of modern music, observing that “the flute of the faun brought new breath to the art of music.” It is a work that barely grasps onto tonality and harmonic function.

About his composition Debussy wrote: The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads, he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature. (see illustration by Manet above and program cover of Nijinsky (dancer) below.

https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51Ah3OP5FjL._AC_UL320_SR232,320_.jpg

Maurice Dumesnil states in his biography of Debussy that Mallarmé was enchanted by Debussy’s composition, citing a short letter from Mallarmé to Debussy that read: “I have just come out of the concert, deeply moved. The marvel! Your illustration of the Afternoon of a Faun, which presents a dissonance with my text only by going much further, really, into nostalgia and into light, with finesse, with sensuality, with richness. I press your hand admiringly, Debussy. Yours, Mallarmé.”

Read some of the poem to have some idea of symbolist poetry and the work upon which Debussy based his composition: English translation of the Mallarme poem (When you get to the site look for the title: après-midi d’un faune and click on it). Read about at this link: symbolist poetry

The opening flute solo of this work is one of the most famous passages in the orchestral repertoire, consisting of a chromatic descent to a tritone below the original pitch, and the subsequent ascent.

Listen to the work:

Remember this work is based on symbolist poetry It is about a Faun which is half human and half animal (See image above) Keep this in mind as you listen.

Listen to the sound file excerpts about half way down the page at this Link to sound file examples (Open in a new window and be sure to scroll down) The sound files here illustrate this work very effectively. The first excerpt is this flute melody which begins the work appears throughout.) Other excerpts , motives and melodies are also presented, below.)

After hearing the brief sound files illustrating parts of this work, listen to the work in its entirety below. Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun was Debussy’s musical response to the poem of Stephane Mallarmé (1842–1898), in which a faun (see illustration above) playing his pan-pipes alone in the woods becomes aroused by passing nymphs and naiads, pursues them unsuccessfully, then wearily abandons himself to a sleep filled with visions. Though called a “prelude,” the work is nevertheless complete – an evocation of the feelings of the poem as a whole.

Musical themes are introduced by woodwinds, with delicate but harmonically advanced underpinnings of muted horns, strings and harp. Recurring styles and techniques make appearances in this piece, namely extended whole-tone scale runs, harmonic fluidity without lengthy modulations between central keys, and tritones in both melody and harmony.

The composition totals 110 bars. If one counts the incomplete lines of verse as one, Mallarmé’s text likewise adds up to 110 lines. The second section in D-flat starts at bar 55:00, exactly halfway through the work.

Now listen to the work in its entirety:

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=709&action=edit

Like Debussy, Ravel is considered one of the leading composers of impressionist music, though, like Debussy, he disliked that label. There are some pieces by Ravel that clearly do not follow impressionistic practice. However, his ballet Daphnis and Chloe is a clear example of impressionist style. We will study him as part of our consideration of the impressionist movement.

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (1875– 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In the 1920s and ’30s Ravel was internationally regarded as France’s greatest living composer.

Ravel attended France’s premier music college, the Paris Conservatoire. After leaving the conservatoire Ravel found his own way as a composer, developing a style of great clarity, incorporating elements of baroque, neoclassicism and, in his later works, jazz. He liked to experiment with musical form, as in his best-known work, Boléro (1928), in which repetition takes the place of development. He made some orchestral arrangements of other composers’ music, of which his 1922 version of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition is the best known.

Ravel was among the first composers to recognise the potential of recording to bring their music to a wider public. From the 1920s, despite limited technique as a pianist or conductor, he took part in recordings of several of his works; others were made under his supervision.

Ravel and Debussy

Around 1900 Ravel and a number of innovative young artists, poets, critics, and musicians joined together in an informal group; they came to be known as Les Apaches (“The Hooligans”), a name coined by Viñes to represent their status as “artistic outcasts.” They met regularly until the beginning of the First World War, and members stimulated one other with intellectual argument and performances of their works. The membership of the group was fluid, and at various times included Igor Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla as well as their French friends.

Among the enthusiasms of the Apaches was the music of Debussy. Ravel, twelve years his junior, had known Debussy slightly since the 1890s, and their friendship, though never close, continued for more than ten years.Revel regarded Debussy as follows: “For Debussy, the musician and the man, I have had profound admiration, but by nature I am different from Debussy .I think I have always personally followed a direction opposed to that of [his] symbolism.”.

Daphnis et Chloé was commissioned in or about 1909 by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev for his company, the Ballets Russes. Ravel began work with Diaghilev’s choreographer, Michel Fokine, and designer, Léon Bakst. Fokine had a reputation for his modern approach to dance, with individual numbers replaced by continuous music. This appealed to Ravel.

In 1913, together with Debussy, Ravel was among the musicians present at the dress rehearsal of The Rite of Spring. Stravinsky later said that Ravel was the only person who immediately understood the music. Ravel predicted that the premiere of the Rite would be seen as an event of historic importance equal to that of Pelléas et Mélisande.

Music:

Ravel drew on many generations of French composers from Couperin and Rameau to Fauré and the more recent innovations of Satie and Debussy. Foreign influences include Mozart, Schubert, Liszt and Chopin. He considered himself in many ways a classicist, often using traditional structures and forms, such as the ternary, to present his new melodic and rhythmic content and innovative harmonies. The influence of jazz on his later music is heard within conventional classical structures in the Piano Concerto and the Violin Sonata.

Whatever sauce you put around the melody is a matter of taste. What is important is the melodic line.

—Ravel to Vaughan Williams

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/vccs-tcc-mus121-1/wp-admin/post.php?post=710&action=edit

Read this article on Ravel’s ballet Daphnis et Chloe. This page just discusses Part III, as that is the portion of the ballet that our listening example comes from. If you’d like to read about the entire scenario of the ballet—which I hope you will—you can read the rest of the Wikipedia article here. (scroll down to find the information

Part III – Scenario

Morning at the grotto of the Nymphs. There is no sound but the murmur of rivulets produced by the dew that trickles from the rocks. Daphnis lies, still unconscious, at the entrance of the grotto. Gradually the day breaks. The songs of birds are heard. Far off, a shepherd passes with his flock. Another shepherd crosses in the background. A group of herdsmen enters looking for Daphnis and Chloe. They discover Daphnis and wake him. Anxiously he looks around for Chloe. She appears at last, surrounded by shepherdesses. They throw themselves into each other’s arms. Daphnis notices Chloe’s wreath. His dream was a prophetic vision. The intervention of Pan is manifest. The old shepherd Lammon explains that, if Pan has saved Chloe, it is in memory of the nymph Syrinx, whom the god once loved. Daphnis and Chloe mime the tale of Pan and Syrinx. Chloe plays the young nymph wandering in the meadow. Daphnis as Pan appears and declares his love. The nymph rebuffs him. The god becomes more insistent. She disappears into the reeds. In despair, he picks several stalks to form a flute and plays a melancholy air. Chloe reappears and interprets in her dance the accents of the flute. The dance becomes more and more animated and, in a mad whirling, Chloe falls into Daphnis’s arms. Before the altar of the Nymphs, he pledges his love, offering a sacrifice of two sheep. A group of girls enters dressed as bacchantes, shaking tambourines. Daphnis and Chloe embrace tenderly. A group of youths rushes on stage and the ballet ends with a bacchanale.

Structure

- Lever du jour

- Pantomime (Les amours de Pan et Syrinx)

- Danse générale (Bacchanale)