Learning Objectives

- Explain the relationship between language and thinking

What Do You Think?: The Meaning of Language

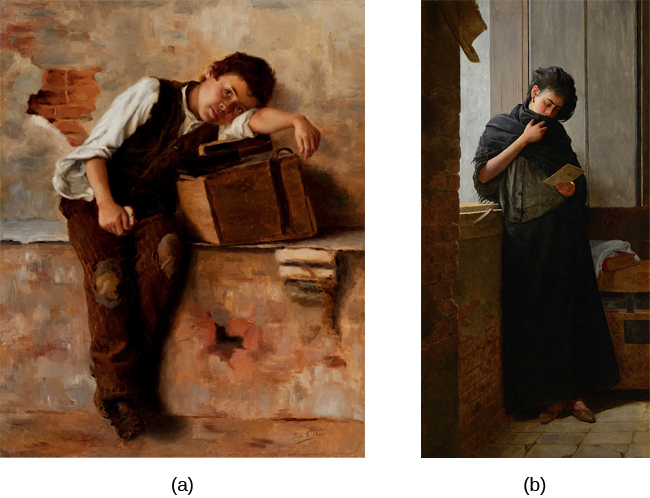

Think about what you know of other languages; perhaps you even speak multiple languages. Imagine for a moment that your closest friend fluently speaks more than one language. Do you think that friend thinks differently, depending on which language is being spoken? You may know a few words that are not translatable from their original language into English. For example, the Portuguese word saudade originated during the 15th century, when Portuguese sailors left home to explore the seas and travel to Africa or Asia. Those left behind described the emptiness and fondness they felt as saudade (Figure 1). The word came to express many meanings, including loss, nostalgia, yearning, warm memories, and hope. There is no single word in English that includes all of those emotions in a single description. Do words such as saudade indicate that different languages produce different patterns of thought in people? What do you think??

Figure 1. These two works of art depict saudade. (a) Saudade de Nápoles, which is translated into “missing Naples,” was painted by Bertha Worms in 1895. (b) Almeida Júnior painted Saudade in 1899.

Language may indeed influence the way that we think, an idea known as linguistic determinism. One recent demonstration of this phenomenon involved differences in the way that English and Mandarin Chinese speakers talk and think about time. English speakers tend to talk about time using terms that describe changes along a horizontal dimension, for example, saying something like “I’m running behind schedule” or “Don’t get ahead of yourself.” While Mandarin Chinese speakers also describe time in horizontal terms, it is not uncommon to also use terms associated with a vertical arrangement. For example, the past might be described as being “up” and the future as being “down.” It turns out that these differences in language translate into differences in performance on cognitive tests designed to measure how quickly an individual can recognize temporal relationships. Specifically, when given a series of tasks with vertical priming, Mandarin Chinese speakers were faster at recognizing temporal relationships between months. Indeed, Boroditsky (2001) sees these results as suggesting that “habits in language encourage habits in thought” (p. 12).

Language does not completely determine our thoughts—our thoughts are far too flexible for that—but habitual uses of language can influence our habit of thought and action. For instance, some linguistic practice seems to be associated even with cultural values and social institution. Pronoun drop is the case in point. Pronouns such as “I” and “you” are used to represent the speaker and listener of a speech in English. In an English sentence, these pronouns cannot be dropped if they are used as the subject of a sentence. So, for instance, “I went to the movie last night” is fine, but “Went to the movie last night” is not in standard English. However, in other languages such as Japanese, pronouns can be, and in fact often are, dropped from sentences. It turned out that people living in those countries where pronoun drop languages are spoken tend to have more collectivistic values (e.g., employees having greater loyalty toward their employers) than those who use non–pronoun drop languages such as English (Kashima & Kashima, 1998). It was argued that the explicit reference to “you” and “I” may remind speakers the distinction between the self and other, and the differentiation between individuals. Such a linguistic practice may act as a constant reminder of the cultural value, which, in turn, may encourage people to perform the linguistic practice.

One group of researchers who wanted to investigate how language influences thought compared how English speakers and the Dani people of Papua New Guinea think and speak about color. The Dani have two words for color: one word for light and one word for dark. In contrast, the English language has 11 color words. Researchers hypothesized that the number of color terms could limit the ways that the Dani people conceptualized color. However, the Dani were able to distinguish colors with the same ability as English speakers, despite having fewer words at their disposal (Berlin & Kay, 1969). A recent review of research aimed at determining how language might affect something like color perception suggests that language can influence perceptual phenomena, especially in the left hemisphere of the brain. You may recall from earlier chapters that the left hemisphere is associated with language for most people. However, the right (less linguistic hemisphere) of the brain is less affected by linguistic influences on perception (Regier & Kay, 2009)

Link to Learning

Learn more about language, language acquisition, and especially the connection between language and thought in the following CrashCourse video:

You can view the transcript for “Language: Crash Course Psychology #16” here (opens in new window).

Try It

Glossary

Candela Citations

- Modification and adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Language. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/7-2-language. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Paragraph on pronoun drop. Authored by: Yoshihisa Kashima . Provided by: University of Melbourne. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/textbooks/wendy-king-introduction-to-psychology-the-full-noba-collection/modules/language-and-language-use. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Language: Crash Course Psychology #16. Authored by: CrashCourse. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9shPouRWCs&feature=youtu.be&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtOPRKzVLY0jJY-uHOH9KVU6. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License