Learning Objectives

- Describe the symptoms, risk factors, influences, and prevalence of autism spectrum disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorder

A seminal paper published in 1943 by psychiatrist Leo Kanner described an unusual neurodevelopmental condition he observed in a group of children. Kanner called this condition early infantile autism, and it was characterized mainly by an inability to form close emotional ties with others, speech and language abnormalities, repetitive behaviors, and an intolerance of minor changes in the environment and in normal routines (Bregman, 2005). What the DSM-5 refers to as autism spectrum disorder today is a direct extension of Kanner’s work.

In 2013, the DSM-5 replaced the previous subgroups of autistic disorder (Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and childhood disintegrative disorder) with the single term autism spectrum disorder.

Figure 1. Few children who are correctly diagnosed with ASD are thought to lose this diagnosis due to treatment or outgrowing their symptoms. Children with poor treatment outcomes also tend to be ones that have moderate to severe forms of ASD, whereas children who appear to have responded to treatment are the ones with milder forms of ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is probably the most misunderstood and puzzling of neurodevelopmental disorders. Children with this disorder show signs of significant disturbances in three main areas: (a) deficits in social interaction, (b) deficits in communication, and (c) repetitive patterns of behavior or interests. These disturbances appear early in life and cause serious impairments in functioning (APA, 2013). The child with autism spectrum disorder might exhibit deficits in social interaction by not initiating conversations with other children or turning their head away when spoken to. These children do not make eye contact with others and seem to prefer playing alone rather than with others. In a certain sense, it is almost as though these individuals live in a personal and isolated social world others are simply not privy to or able to penetrate. Communication deficits can range from a complete lack of speech, to one-word responses (e.g., saying “Yes” or “No” when replying to questions or statements that require additional elaboration), to echoed speech (e.g., parroting what another person says, either immediately or several hours or even days later), to difficulty maintaining a conversation because of an inability to reciprocate others’ comments. These deficits can also include problems in using and understanding nonverbal cues (e.g., facial expressions, gestures, and postures) that facilitate normal communication.

Repetitive patterns of behavior or interests can be exhibited in a number of ways. A child with autism spectrum disorder might engage in stereotyped, repetitive movements (rocking, head-banging, or repeatedly dropping an object and then picking it up) or might show great distress at small changes in routine or the environment. For example, the child might throw a temper tantrum if an object is not in its proper place or if a regularly-scheduled activity is rescheduled. In some cases, the person with autism spectrum disorder might show highly restricted and fixated interests that appear to be abnormal in their intensity. For instance, the person might learn and memorize every detail about something even though doing so serves no apparent purpose. Importantly, autism spectrum disorder is not the same thing as intellectual development disorder (intellectual disability), although these two conditions are often comorbid. The DSM-5 specifies that the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder are not caused or explained by intellectual development disorder.

Life Problems from Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder is referred to in everyday language as autism; in fact, the disorder was termed autistic disorder in earlier editions of the DSM, and its diagnostic criteria were much narrower than those of autism spectrum disorder. The qualifier spectrum in autism spectrum disorder is used to indicate that individuals with the disorder can show a range, or spectrum, of symptoms that vary in their magnitude and severity: some severe, others less severe. The previous edition of the DSM included a diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder, generally recognized as a less severe form of autistic disorder; individuals diagnosed with Asperger’s disorder were described as having average or high intelligence and a strong vocabulary, but exhibiting impairments in social interaction and social communication, such as talking only about their special interests (Wing, Gould, & Gillberg, 2011). However, because research has failed to demonstrate that Asperger’s disorder differs qualitatively from autistic disorder, the DSM-5 dropped the distinction. Some individuals with autism spectrum disorder, particularly those with better language and intellectual skills, can live and work independently as adults. However, most do not because the symptoms remain sufficient to cause serious impairment in many areas of life (APA, 2013).

Watch It

This video provides an overview of what you’ve read, describing its diagnostic criteria and the differences between the DSM-4 and DSM-5 terms for ASD.

You can view the transcript for “Autism Spectrum Disorder | Clinical Presentation” here (opens in new window).

Epidemiology

Current estimates from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network indicate that one in 59 children in the United States has autism spectrum disorder; the disorder is four times more common among boys (one in 38) than in girls (one in 152) (Baio et al, 2018). Rates of autistic spectrum disorder have increased dramatically since the 1980s. For example, California saw an increase of 273% in reported cases from 1987 through 1998 (Byrd, 2002); between 2000 and 2008, the rate of autism diagnoses in the United States increased 78% (CDC, 2012). Although it is difficult to interpret this increase, it is possible that the rise in prevalence is the result of the broadening of the diagnosis, increased efforts to identify cases in the community, and greater awareness and acceptance of the diagnosis. In addition, mental health professionals are now more knowledgeable about autism spectrum disorder and are better equipped to make the diagnosis, even in subtle cases (Novella, 2008).

Try It

Causes of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Figure 2. Another controversial claim suggested that watching extensive amounts of television caused autism. This hypothesis was largely based on research suggesting that the increasing rates of autism in the 1970s and 1980s were linked to the growth of cable television at this time.

Early theories of autism placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of the child’s parents, particularly the mother. Bruno Bettelheim (an Austrian-born American child psychologist who was heavily influenced by Sigmund Freud’s ideas) suggested that a mother’s ambivalent attitudes and her frozen and rigid emotions toward her child were the main causal factors in childhood autism. In what must certainly stand as one of the more controversial assertions in psychology over the last 50 years, Bettelheim wrote, “I state my belief that the precipitating factor in infantile autism is the parent’s wish that his child should not exist” (Bettelheim, 1967, p. 125). As you might imagine, Bettelheim did not endear himself to a lot of people with this position; incidentally, no scientific evidence exists supporting his claims.

The exact causes of autism spectrum disorder remain unknown despite massive research efforts over the last two decades (Meek, Lemery-Chalfant, Jahromi, & Valiente, 2013). Autism appears to be strongly influenced by genetics, as identical twins show concordance rates of 60–90%, whereas concordance rates for fraternal twins and siblings are five to 10% (Autism Genome Project Consortium, 2007). Many different genes and gene mutations have been implicated in autism (Meek et al., 2013). Among the genes involved are those important in the formation of synaptic circuits that facilitate communication between different areas of the brain (Gauthier et al., 2011). A number of environmental factors are also thought to be associated with increased risk for autism spectrum disorder, at least in part, because they contribute to new mutations. These factors include exposure to pollutants, such as plant emissions and mercury, urban versus rural residence, and vitamin D deficiency (Kinney, Barch, Chayka, Napoleon, & Munir, 2009).

Certain prenatal and perinatal complications have been reported as possible risk factors for autism. These risk factors include maternal gestational diabetes, maternal and paternal age over 30, bleeding after the first trimester, use of prescription medication (e.g. valproate) during pregnancy, and meconium in the amniotic fluid. While research is not conclusive on the relation of these factors to autism, each of these factors has been identified more frequently in children with autism compared to their siblings who do not have autism, and other typically developing youth. While it is unclear if any single factors during the prenatal phase affect the risk of autism, complications during pregnancy may be a risk. Another hypothesized risk factor is low vitamin D levels in early development.

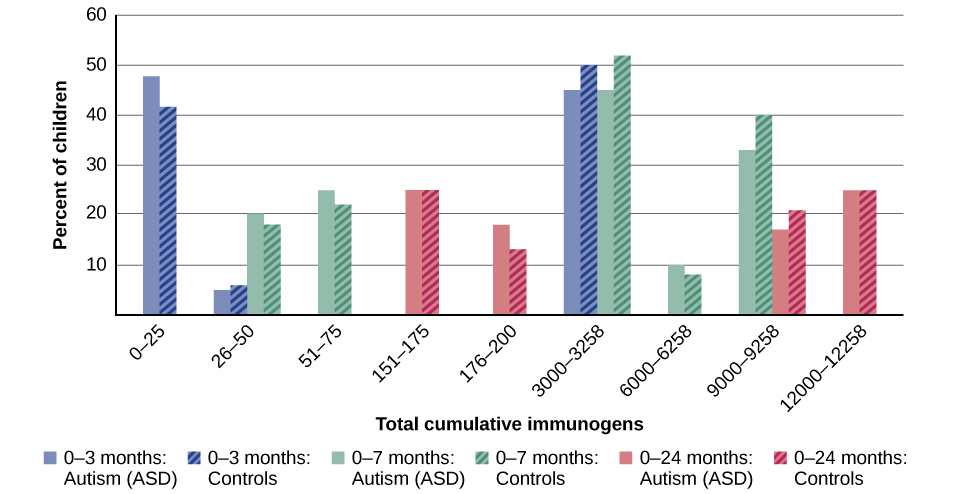

Child Vaccinations and Autism Spectrum Disorder

In the late 1990s, a prestigious medical journal published an article purportedly showing that autism is triggered by the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine. These findings were very controversial and drew a great deal of attention, sparking an international forum on whether children should be vaccinated. In a shocking turn of events, some years later, the article was retracted by the journal that had published it after accusations of fraud on the part of the lead researcher. Despite the retraction, the reporting in popular media led to concerns about a possible link between vaccines and autism persisting. A recent survey of parents, for example, found that roughly a third of respondents expressed such a concern (Kennedy, LaVail, Nowak, Basket, & Landry, 2011); and perhaps fearing that their children would develop autism, more than 10% of parents of young children refuse or delay vaccinations (Dempsey et al., 2011). Some parents of children with autism mounted a campaign against scientists who refuted the vaccine-autism link. Even politicians and several well-known celebrities weighed in; for example, actress Jenny McCarthy (who believed that a vaccination caused her son’s autism) co-authored a book on the matter. However, there is no scientific evidence that a link exists between autism and vaccinations (Hughes, 2007). Indeed, a recent study compared the vaccination histories of 256 children with autism spectrum disorder with that of 752 control children across three time periods during their first two years of life (birth to three months, birth to seven months, and birth to two years) (DeStefano, Price, & Weintraub, 2013). At the time of the study, the children were between six and 13 years old, and their prior vaccination records were obtained. Because vaccines contain immunogens (substances that fight infections), the investigators examined medical records to see how many immunogens children received to determine if those children who received more immunogens were at greater risk for developing autism spectrum disorder. The results of this study, a portion of which are shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, clearly demonstrate that the quantity of immunogens from vaccines received during the first two years of life were not at all related to the development of autism spectrum disorder. There is not a relationship between vaccinations and autism spectrum disorders.

Figure 3. In terms of their exposure to immunogens in vaccines, overall, there is not a significant difference between children with autism spectrum disorder and their age-matched controls without the disorder (DeStefano et al., 2013).

| Total Cumulative Immunogens | 0 to 3 Months: Autism (ASD) | 0 to 3 Months: Controls | 0 to 7 Months: Autism (ASD) | 0 to 7 Months: Controls | 0 to 24 Months: Autism (ASD) | 0 to 24 Months: Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 25 | 48% | 41% | – | – | – | – |

| 26 to 50 | 5% | 6% | 20% | 18% | – | – |

| 51 to 75 | – | – | 25% | 22% | – | – |

Why does concern over vaccines and autism spectrum disorder persist? Since the proliferation of the internet in the 1990s, parents have been constantly bombarded with online information that can become magnified and take on a life of its own. The enormous volume of electronic information pertaining to autism spectrum disorder, combined with how difficult it can be to grasp complex scientific concepts, can make separating good research from bad challenging (Downs, 2008). Notably, the study that fueled the controversy reported that eight out of 12 children—according to their parents—developed symptoms consistent with autism spectrum disorder shortly after receiving a vaccination. To conclude that vaccines cause autism spectrum disorder on this basis, as many did, is clearly incorrect for a number of reasons, not the least of which is because correlation does not imply causation, as you’ve learned.

Additionally, as was the case with diet and ADHD in the 1970s, the notion that autism spectrum disorder is caused by vaccinations is appealing to some because it provides a simple explanation for this condition. Like all disorders, however, there are no simple explanations for autism spectrum disorder. Although the research discussed above has shed some light on its causes, science is still a long way from a complete understanding of the disorder.

Try It

Treatments for Autism Spectrum Disorder

Several interventions can help children with autism, and the main goals of treatment are to lessen associated deficits and family distress and to increase quality of life and functional independence. In general, higher IQs are correlated with greater responsiveness to treatment and improved treatment outcomes. Although evidence-based interventions for autistic children vary in their methods, many adopt a psychoeducational approach to enhancing cognitive, communication, and social skills while minimizing problem behaviors. It’s important to keep in mind that no single treatment is best, there is no “one-size-fits-all” solution, and treatment should be tailored to the child’s needs. Intensive, sustained special education or remedial education programs and behavior therapy early in life can help children acquire self-care, social, and job skills. Available approaches include applied behavior analysis (ABA), developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, social skills therapy, and occupational therapy. Among these approaches, interventions either treat autistic features comprehensively or focus treatment on a specific area of deficit.

There has been increasing attention to the development of evidence-based interventions for young children with ASD. Two theoretical frameworks outlined for early childhood intervention include applied behavioral analysis (ABA) and the developmental social-pragmatic model (DSP). Although applied behavioral analysis (ABA) therapy has a strong evidence base, particularly in regard to early intensive home-based therapy, ABA’s effectiveness may be limited by diagnostic severity and the IQ of the person affected by ASD.

Neurodiversity

The autism rights movement promotes the concept of neurodiversity, which views autism as a natural variation of the brain rather than a disorder to be cured. In response to the rising idea that autism (and other similar disorders) are an epidemic, the concept of neurodiversity shines a new perspective on the subject.

Figure 4. The symbol for the Autism Rights Movement.

Coined in 1998 by Australian sociologist Judy Singer, who helped popularize the concept along with American journalist Harvey Blume, neurodiversity emerged as a challenge to prevailing views that certain neurodevelopmental disorders are inherently pathological and instead adopts the social model of disability, in which societal barriers are the main contributing factor that disables people. The term represented a move away from previous “mother-blaming” theories about the cause of autism.

Neurodiversity advocates point out that neurodiverse people often have exceptional abilities alongside their weaknesses. For example, a person with ADHD may hyperfocus on some tasks while struggling to focus on others, or an autistic person may have exceptional memory or even savant skills. In light of these facts, advocates argue for recognition of strengths as well as weaknesses in neurodiverse people, and that a variety of neurological conditions that are currently classified as disorders are better regarded as differences. This view is especially popular within the autism rights movement.

Neurodiversity advocates denounce the framing of autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other neurodevelopmental disorders as requiring medical intervention to “cure” or “fix” them and instead promote support systems, such as inclusion-focused services, accommodations, communication, and assistive technologies, occupational training, and independent living support. The intention is for individuals to receive support that honors authentic forms of human diversity, self-expression, and being, rather than treatment that coerces or forces them to adopt normative ideas of normality or to conform to a clinical ideal. Proponents of neurodiversity strive to reconceptualize autism and related conditions in society by the following measures: acknowledging that neurodiversity does not require a cure; changing the language from the current “condition, disease, disorder, or illness”-based nomenclature, and “broaden[ing] the understanding of healthy or independent living”; acknowledging new types of autonomy; and giving non-neurotypical individuals more control over their treatment, including the type, timing, and whether there should be treatment at all.

However, the neurodiversity paradigm has been controversial among disability advocates, with opponents saying that its conceptualization doesn’t reflect the realities of individuals who have high-support needs.

Key Takeaways: Autism Spectrum Disorder

Glossary

autism spectrum disorder: childhood disorder characterized by deficits in social interaction and communication and repetitive patterns of behavior or interests

neurodevelopmental disorder: disorders that are first diagnosed in childhood and involve developmental problems in academic, intellectual, and social functioning

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Chrissy Hicks for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Autism spectrum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autism_spectrum. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Disorders in Childhood. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:uASZ6djG@5/Disorders-in-Childhood. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

- Girl watching tv. Authored by: oddharmonic. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2405784549_264fe67e22_z_copy.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- pastel neurodiversity image. Authored by: mrmw. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autism_rights_movement#/media/File:Neurodiversity_Symbol.svg. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Autism Spectrum Disorder | Clinical Presentation. Provided by: MedScape. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=FCejya1WWC8&feature=emb_logo. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- boy sitting. Provided by: Pxhere. Located at: https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1402620. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved