Learning Objectives

- Describe symptoms and factors associated with narcolepsy

- Describe symptoms and factors associated with hypersomnolence disorder

Narcolepsy

Figure 1. Those with narcolepsy may have a difficult time staying awake at work.

A person with narcolepsy cannot resist falling asleep at inopportune times. These sleep episodes are often associated with cataplexy, which is a lack of muscle tone or muscle weakness, and in some cases involves complete paralysis of the voluntary muscles similar to the kind of paralysis experienced by healthy individuals during REM sleep (Burgess & Scammell, 2012; Hishikawa & Shimizu, 1995; Luppi et al., 2011). Narcoleptic episodes take on other features of REM sleep. For example, around one-third of individuals diagnosed with narcolepsy experience vivid, dream-like hallucinations during narcoleptic attacks (Chokroverty, 2010).

Surprisingly, narcoleptic episodes are often triggered by states of heightened arousal or stress. The typical episode can last from a minute or two to half an hour. Once awakened from a narcoleptic attack, people report that they feel refreshed (Chokroverty, 2010). Obviously, regular narcoleptic episodes could interfere with the ability to perform one’s job or complete schoolwork, and in some situations, narcolepsy can result in significant harm and injury (e.g., driving a car or operating machinery or other potentially dangerous equipment).

In order to make a diagnosis of narcolepsy, an individual must have symptoms occurring at least three times a week over the past three months. In addition, one of the following must be present:

- hypocretin deficiency

- episodes of cataplexy occurring at least several times a month

- REM sleep latency of fewer than 15 minutes or two or more sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs) and a mean sleep latency of fewer than eight minutes.

Etiology

Narcolepsy affects both males and females equally. Symptoms often start in childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood (ages seven to 25), but can occur at any time in life. It is estimated that anywhere from 135,000 to 200,000 people in the United States have narcolepsy. However, since this condition often goes undiagnosed, the number may be higher. Since people with narcolepsy are often misdiagnosed with other conditions, such as psychiatric disorders or emotional problems, it can take years for someone to get the proper diagnosis. There are two types: narcolepsy type 1 (formerly narcolepsy with cataplexy) and narcolepsy type 2 (formerly narcolepsy without cataplexy).

Narcolepsy may have several causes. Nearly all people with narcolepsy type 1 (with cataplexy) have extremely low levels of the naturally occurring chemical hypocretin, which promotes wakefulness and regulates REM sleep. Hypocretin levels are usually normal in people who have narcolepsy type 2 (without cataplexy). Although the cause of narcolepsy is not completely understood, current research suggests that narcolepsy may be the result of a combination of factors working together to cause a lack of hypocretin. These factors include

- autoimmune disorders. When cataplexy is present, the cause is most often the loss of brain cells that produce hypocretin. Although the reason for this cell loss is unknown, it appears to be linked to abnormalities in the immune system. Autoimmune disorders occur when the body’s immune system turns against itself and mistakenly attacks healthy cells or tissue. Researchers believe that in individuals with narcolepsy, the body’s immune system selectively attacks the hypocretin-containing brain cells because of a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- family history. Most cases of narcolepsy are sporadic, meaning the disorder occurs in individuals with no known family history. However, clusters in families sometimes occur—up to 10% of individuals diagnosed with narcolepsy type 1 (with cataplexy) report having a close relative with similar symptoms.

- brain injuries. Rarely, narcolepsy results from traumatic injury to parts of the brain that regulate wakefulness and REM sleep or from tumors and other diseases in the same regions.

Treatment

Although there is no cure for narcolepsy, some of the symptoms can be treated with medicines and lifestyle changes. When cataplexy is present, the loss of hypocretin is believed to be irreversible and lifelong. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and cataplexy can be controlled in most individuals with medications.

Medications

- Modafinil. The initial line of treatment is usually a central nervous system stimulant such as modafinil. Modafinil is usually prescribed first because it is less addictive and has fewer side effects than older stimulants. For most people, these drugs are generally effective at reducing daytime drowsiness and improving alertness.

- Amphetamines. Generally, narcolepsy is treated using psychomotor stimulant drugs, such as amphetamines (Mignot, 2012). These drugs promote increased levels of neural activity. Narcolepsy is associated with reduced levels of the signaling molecule hypocretin in some areas of the brain (De la Herrán-Arita & Drucker-Colín, 2012; Han, 2012), and traditional stimulant drugs do not have direct effects on this system. Therefore, it is quite likely that new medications that are developed to treat narcolepsy will be designed to target the hypocretin system.

- Amphetamine-like stimulants. In cases where modafinil is not effective, doctors may prescribe amphetamine-like stimulants such as methylphenidate to alleviate EDS. However, these medications must be carefully monitored because they can have side effects like irritability and nervousness, shakiness, disturbances in heart rhythm, and night-time sleep disruption. In addition, health care professionals should be careful when prescribing these drugs and people should be careful using them because the potential for abuse is high with any amphetamine.

- Antidepressants. Two classes of antidepressant drugs have proven effective in controlling cataplexy in many individuals: tricyclics (including imipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, and protriptyline) and selective serotonin and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors (including venlafaxine, fluoxetine, and atomoxetine). In general, antidepressants produce fewer adverse effects than amphetamines. However, troublesome side effects still occur in some individuals, including impotence, high blood pressure, and heart rhythm irregularities.

- Sodium oxybate. Sodium oxybate (also known as gamma hydroxybutyrate or GHB) has been approved by the FDA to treat cataplexy and excessive daytime sleepiness in individuals with narcolepsy. It is a strong sedative that must be taken twice a night. Due to safety concerns associated with the use of this drug, the distribution of sodium oxybate is tightly restricted

Lifestyle changes

Not everyone with narcolepsy can consistently maintain a fully normal state of alertness using currently available medications. Drug therapy should accompany various lifestyle changes. The following strategies may be helpful:

- Take short naps. Many individuals take short, regularly scheduled naps at times when they tend to feel sleepiest.

- Maintain a regular sleep schedule. Going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, even on the weekends, can help people sleep better.

- Avoid caffeine or alcohol before bed. Individuals should avoid alcohol and caffeine for several hours before bedtime.

- Avoid smoking. Individuals should avoid smoking, especially at night.

- Exercise daily. Exercising for at least 20 minutes per day at least four or five hours before bedtime also improves sleep quality and can help people with narcolepsy avoid gaining excess weight.

Figure 2. A relaxing bath before bed may contribute to a better night’s sleep and sleep schedule, which can help in treating narcolepsy.

- Avoid large, heavy meals right before bedtime. Eating very close to bedtime can make it harder to sleep.

- Relax before bed. Relaxing activities such as a warm bath before bedtime can help promote sleepiness. Also, make sure the sleep space is cool and comfortable.

- Take safety precautions. Safety precautions, particularly when driving, are important for everyone with narcolepsy. People with untreated symptoms are more likely to be involved in automobile accidents, although the risk is lower among individuals who are taking appropriate medication. EDS and cataplexy can lead to serious injury or death if left uncontrolled. Suddenly falling asleep or losing muscle control can transform actions that are ordinarily safe, such as walking down a long flight of stairs, into hazards.

- Modify work/school schedules. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations for all employees with disabilities. Adults with narcolepsy can often negotiate with employers to modify their work schedules so they can take naps when necessary and perform their most demanding tasks when they are most alert. Similarly, children and adolescents with narcolepsy may be able to work with school administrators to accommodate special needs, like taking medications during the school day, modifying class schedules to fit in a nap, and other strategies.

- Participate in support groups. Additionally, support groups can be extremely beneficial for people with narcolepsy who want to develop better coping strategies or feel socially isolated due to embarrassment about their symptoms. Support groups also provide individuals with a network of social contacts who can offer practical help and emotional support.

There is a tremendous amount of variability among sufferers, both in terms of how symptoms of narcolepsy manifest and the effectiveness of currently available treatment options. This variation is illustrated by McCarty’s (2010) case study of a 50-year-old woman who sought help for the excessive sleepiness during normal waking hours that she had experienced for several years. She indicated that she had fallen asleep at inappropriate or dangerous times, including while eating, while socializing with friends, and while driving her car. During periods of emotional arousal, the woman complained that she felt some weakness in the right side of her body. Although she did not experience any dream-like hallucinations, she was diagnosed with narcolepsy as a result of sleep testing. In her case, the fact that her cataplexy was confined to the right side of her body was quite unusual. Early attempts to treat her condition with a stimulant drug alone were unsuccessful. However, when a stimulant drug was used in conjunction with a popular antidepressant, her condition improved dramatically.

Try It

Watch It

Watch this video about Michelle, who suffered from narcolepsy when she experienced emotional distress. She describes her symptoms with sleep disturbances, her diagnosis, and how she was empowered by her diagnosis.

You can view the transcript for “What Is Narcolepsy?” here (opens in new window).

Key Takeaways: Narcolepsy

Hypersomnolence Disorder

Hypersomnia is a pathological state characterized by a lack of alertness during the waking episodes of the day. Hypersomnia is not to be confused with fatigue, which is a normal physiological state. Daytime sleepiness appears most commonly during situations where little interaction is needed. Hypersomnolence disorder affects approximately 5% of the population and is more common in men than females.[1]

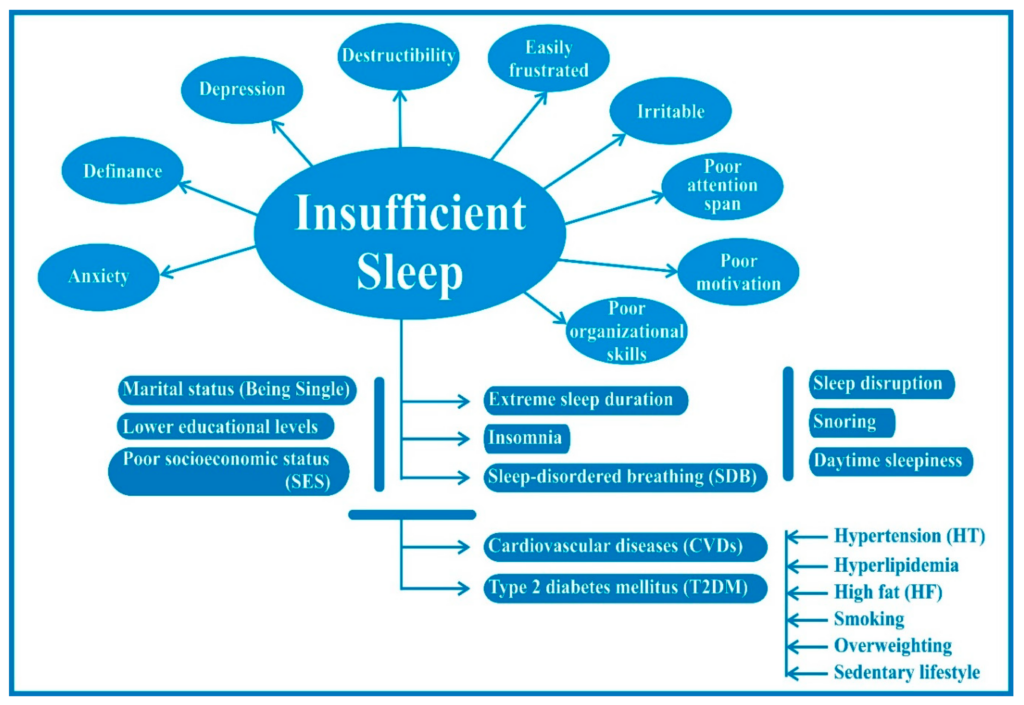

Figure 1. Insufficient sleep poses major health risks throughout a person’s lifetime.

In 2008, the CDC examined data from over 400,000 subjects throughout the United States and found that 11.1% reported that they had had insufficient rest or sleep every day during the preceding 30 days. Females (12.4%) were more likely than males (9.9%), and non-Hispanic blacks (13.3%) were more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to report insufficient rest or sleep. A recent study conducted among Korean adults (19 years and older) found that the prevalence of excessive day sleepiness was 11.9%. A recent cross-sectional Japanese study, which used a web-based questionnaire to ask about health-related quality of life issues, found that respondents aged 20 to 25 years and who were either students or full-time employees (11% of the sample), reported that they suffered from insufficient sleep syndrome.[2]