Learning Objectives

- Identify and describe the diagnostic criteria and major symptoms of schizophrenia

- Differentiate between the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a complex and significant psychological disorder characterized by major disturbances in thought, perception, emotion, and behavior. About 1% of the population experiences schizophrenia in their lifetime (i.e., over three million people in the United States alone), and usually, the disorder is first diagnosed during early adulthood (early to mid-20s). Most people with schizophrenia experience significant difficulties in many day-to-day activities, such as holding a job, paying bills, caring for oneself (grooming and hygiene), and maintaining relationships with others. However, contrary to common assumptions, a recent review of studies on schizophrenia (Vita & Barlati, 2018[1]) found a wide range of outcomes for persons who have schizophrenia, ranging from persons with severe symptoms and repeated episodes of remission and subsequent hospitalization to persons who experience a single episode that meets criteria followed by complete remission (although they usually continue to participate in treatment). Vita and Barlati (2018) also found that possibly up to half of the individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia either recovered or demonstrated significant improvement over time. They recommended that clinicians and society focus on two outcomes of consideration for persons with schizophrenia: clinical remission (significant reduction of symptoms and severity) and social functioning (e.g., ability to work, to function as a family member or in relationships, enjoy recreation, and dwell in independent living) in thinking about recovery.

Unlike other conditions such as depression or anxiety that almost all people can relate to in some ways, it is more difficult for most people to see the symptoms of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders as part of the normal continuum of human experiences. However, the types of psychotic symptoms that characterize disorders like schizophrenia are on a continuum with normal mental experiences. For example, work by Jim van Os in the Netherlands has shown that a surprisingly large percentage of the general population (10%+) experience psychotic-like symptoms, though many fewer have multiple experiences and most will not continue to experience these symptoms in the long run (Verdoux & van Os, 2002). Similarly, work in a general population of adolescents and young adults in Kenya has also shown that a relatively high percentage of individuals experience one or more psychotic-like experiences (~19%) at some point in their lives (Mamah et al., 2012; Ndetei et al., 2012), though again most will not go on to develop a full-blown psychotic disorder.

So, what is schizophrenia? It is important to realize that schizophrenia is not a condition involving a split personality; that is, schizophrenia is not the same as dissociative identity disorder (previously known as multiple personality disorder). These disorders are sometimes confused because the word schizophrenia first coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911, derives from Greek words that refer to a “splitting” (schizo) of the mind (phrene) (Green, 2001). In the case of schizophrenia, the “split” is usually interpreted as between cognition (thinking and communicating) and emotions (see the discussion of flat affect below). Schizophrenia is considered a psychotic disorder (while dissociative disorders are not), which impairs a person’s thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors to the point where that individual is not able to function normally in life. Individuals who suffer from psychotic disorders experience a major disconnection with the world around them and do not share in the normal perception of the external environment. In other words, terms like psychosis or psychotic do not have anything to do with violence, serial killers, or other common misunderstandings; psychosis refers specifically to the presence of hallucinations (sensory distortions), delusions (unusual beliefs), or disorganized thought processes and can also occur during severe instances with other disorders.

Schizophrenia was once classified into distinct subtypes, such as paranoid, catatonic, disorganized, residual, or undifferentiated, but that method has since been replaced by approaching schizophrenia as a spectrum of disorders with varying degrees of severity and displaying several aspects of the subtypes. Now, schizophrenia subtypes are not listed in the DSM-5, as the subtypes would often change or coexist, but clinicians still sometimes specify a dominant type of subtype, such as “schizophrenia with paranoia.” The spectrum of psychotic disorders includes schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and psychosis associated with substance use or medical conditions. These are all disorders of psychosis, with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (schizophrenia combined with a mood disorder) being the most severe and personality disorders being less severe.

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

The main symptoms of schizophrenia can be categorized as either positive symptoms or negative symptoms. Positive symptoms are symptoms of addition, meaning they add something atypical or unusual to what other individuals experience, do, or think. Examples include hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thinking and behaviors. Negative symptoms are those that result in noticeable decreases or absences in common behaviors, emotions, or drives (APA, 2013; Green, 2001). Examples include flattened emotional expression, lack of motivation for self-care, or significant social withdrawal.

Positive Symptoms

A hallucination is a perceptual experience that occurs in the absence of external stimulation. Auditory hallucinations (hearing voices) occur in roughly two-thirds of patients with schizophrenia and are by far the most common form of hallucination (Andreasen, 1987). The auditory voices may be familiar or unfamiliar, they may have a conversation or argue, or the voices may provide a running commentary on the person’s behavior (Tsuang, Farone, & Green, 1999).

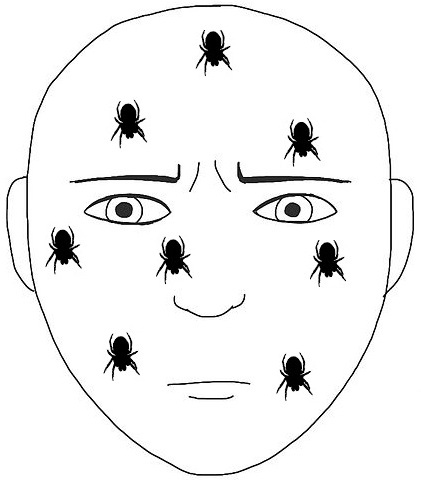

Figure 1. Tactile hallucinations, like that of imaginary spiders crawling on the skin, are another type of hallucination.

Less common are visual hallucinations (seeing things that are not there) and olfactory hallucinations (smelling odors that are not actually present). In interacting with persons with psychotic symptoms, it is helpful to remember that although you may not hear what they are hearing nor see what they are seeing or experiencing, they are having those sensory experiences. To them, these experiences seem as real as you seeing a car drive by on the street or hearing a neighbor’s dog barking. Telling them they are wrong or that those things are not happening does not improve your ability to relate to them or help them reconnect to the world around them. Instead, try to understand what they are experiencing and demonstrate empathy and understanding.

Delusions are beliefs that are contrary to reality and are firmly held even in the face of contradictory evidence. Many of us hold beliefs that some would consider odd, but a delusion is easily identified because it is absurd according to normal social and cultural standards. A person with schizophrenia may believe that his mother is plotting with the FBI to poison his coffee or that his neighbor is an enemy spy who wants to kill him. These kinds of delusions are known as paranoid delusions, which involve the false belief that other people or agencies are plotting against the person. People with schizophrenia also may hold grandiose delusions, which are beliefs that one holds special power, unique knowledge, or is extremely important. For example, the person who claims to be Jesus Christ, or who claims to have knowledge going back 5,000 years, or who claims to be a great philosopher is experiencing grandiose delusions. Other delusions include the belief that one’s thoughts are being removed from their head (thought withdrawal) or thoughts have been placed inside one’s head (thought insertion). Another type of delusion is a somatic delusion, which is the belief that something highly abnormal and improbable is happening to one’s body (e.g., that one’s kidneys are being eaten by cockroaches).

Disorganized thinking refers to disjointed and incoherent thought processes—usually detected by what a person says. Individuals might ramble, exhibit loose associations (jump from topic to topic), or talk in a way that is so disorganized and incomprehensible that it seems as though the person is randomly combining words. Disorganized thinking is also exhibited by blatantly illogical remarks (e.g., “Fenway Park is in Boston. I live in Boston. I live at Fenway Park.”) and by tangentiality: responding to others’ statements or questions by remarks that are either barely related or unrelated to what was said or asked. For example, if a person diagnosed with schizophrenia is asked if she is interested in receiving special job training, she might state that she once rode on a train somewhere. To a person with schizophrenia, the tangential (slightly related) connection between job training and riding a train are sufficient enough to cause such a response.

As another example, at the beginning of an interview, a clinician remarked in passing that he forgot to bring his pen to take notes. The patient begins to talk about living on a farm as a child and taking care of pigs which was tangential to the focus of the conversation. However, there is a linguistic association between “pen” (writing tool) and an animal enclosure (pen) on a farm. In persons without thought disorder or disorganized thinking, the brain would light up with these language associations, but would quickly sort through them and prioritize those that match the context. For someone with schizophrenia, these filters and the ability to determine the appropriate context are usually impaired.

Disorganized or abnormal motor behavior refers to unusual behaviors and movements: becoming unusually active, exhibiting silly child-like behaviors (giggling and self-absorbed smiling), engaging in repeated and purposeless movements, or displaying odd facial expressions and gestures. In some cases, the person will exhibit catatonic behaviors that show decreased reactivity to the external environment, such as posturing, in which the person maintains a rigid and bizarre posture for long periods of time, or catatonic stupor, a complete lack of movement and verbal behavior. Another way catatonia is displayed is through waxy flexibility, which occurs when another person places an individual with schizophrenia in an unusual or uncomfortable position and they remain in that position, sometimes for hours.

Negative Symptoms

Unlike positive symptoms, negative symptoms are symptoms where ordinary and expected behaviors may be reduced or absent. A person who exhibits diminished emotional expression displays little emotion in his facial expressions, speech, or movements, even when such expressions are normal or expected (also known as flat affect where affect is a noun meaning the display of emotion). It is important to recognize, however, that although the person may have difficulty expressing their emotions the way most people do, they still experience the full range of normal human emotions[2]. Avolition (lack of volition) is characterized by a lack of motivation to engage in self-initiated and meaningful activity, including the most basic of daily living tasks such as bathing and grooming. Alogia (lack of speech; from the Greek logos meaning word or speech) refers to reduced speech output; in simple terms, patients do not speak or respond much in interactions with others. Another negative symptom is asociality, or social withdrawal and lack of interest in engaging in social interactions with others (this is differentiated from antisocial activity such as that of persons with antisocial personality disorder who are “against” or “anti” society). A final negative symptom, anhedonia, refers to an inability to experience pleasure. One who exhibits anhedonia expresses little interest in what most people consider to be pleasurable activities, such as hobbies, recreation, or sexual activity.

In their review of schizophrenia research, Vita and Barlati (2018) note that positive symptoms receive much attention, but negative and cognitive symptoms are often not treated effectively, leading persons to not achieve “functional” (or daily living) levels of remission. In addition to the use of some of the newer antipsychotics that may help with negative symptoms, psychosocial treatments are important in reducing negative symptoms and improving the person’s ability to function well in their life.

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia are listed below:

A. Two (or more) of the following must each present for a significant portion of time during a one-month period (or less if successfully treated). At least one of these must be (1), (2), or (3):

- delusions

- hallucinations

- disorganized speech (e.g., frequent derailment or incoherence)

- grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

- negative symptoms (i.e., diminished emotional expression or avolition)

B. For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, level of functioning in one or more major areas, such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care, is markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset (or when the onset is in childhood or adolescence, there is failure to achieve expected level of interpersonal, academic, or occupational functioning).

C. Duration: continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least six months. This six-month period must include at least one month of symptoms (or less if successfully treated) that meet Criterion A (i.e., active-phase symptoms) and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms. During these prodromal or residual periods, the signs of the disturbance may be manifested by only negative symptoms or two or more symptoms listed in Criterion A present in an attenuated form (e.g., odd beliefs or unusual perceptual experiences).[3]

D. Schizoaffective disorder and depressive or bipolar disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either 1) no major depressive or manic episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms or 2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, they have been present for a minority of the total duration of the active and residual periods of the illness.

E. The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effect of a substance (e.g., drug abuse or a medication) or other medical condition.

F. If there is a history of autism spectrum disorder or communication disorder of childhood onset, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations, in addition to the other required symptoms of schizophrenia, are also present for at least one month (or less if successfully treated).[4]

Link to Learning

Watch this video and try to identify which classic symptoms of schizophrenia are shown. See if you can describe the positive and negative symptoms that this individual exhibits.

Try It

Watch It

Watch this video for an overview of schizophrenia, including the causes and symptoms you’ve learned about thus far.

You can view the transcript for “Schizophrenia – causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology” here (opens in new window).

Key Takeaways: Schizophrenia

Try It

Forensic Psychology

In August 2013, 17-year-old Cody Metzker-Madsen attacked five-year-old Dominic Elkins on his foster parents’ property. Believing that he was fighting goblins and that Dominic was the goblin commander, Metzker-Madsen beat Dominic with a brick and then held him face down in a creek. Dr. Alan Goldstein, a clinical and forensic psychologist, testified that Metzker-Madsen believed that the goblins he saw were real and was not aware that it was Dominic at the time. He was found not guilty by reason of insanity and was not held legally responsible for Dominic’s death (Nelson, 2014). Cody was also found to be a danger to himself or others. He will be held in a psychiatric facility until he is judged to be no longer dangerous. This does not mean that he “got away with” anything. In fact, according to the American Psychiatric Association, individuals who are found not guilty by reason of insanity are often confined to psychiatric hospitals for as long or longer than they would have spent in prison for a conviction.

Hollywood depictions and news reports to the contrary, most people with schizophrenia are not violent. Only 3%-5% of violent acts are committed by individuals diagnosed with severe mental illness, whereas individuals with severe mental illnesses are more than 10 times as likely to be victims of crime (MentalHealth.gov, 2017). The most common conditions linked to violence are psychopathic personality (severe antisocial personality disorder), bipolar disorder, and persons who are abusing drugs (especially alcohol). The psychologists who work with individuals such as Metzker-Madsen are part of the subdiscipline of forensic psychology. Forensic psychologists are involved in psychological assessment and treatment of individuals involved with the legal system. They use their knowledge of human behavior and mental illness to assist the judicial and legal system in making decisions in cases involving such issues as personal injury suits, workers’ compensation, competency to stand trial, and pleas of not guilty by reason of insanity.

Glossary

catatonic behavior: decreased reactivity to the environment; includes posturing and catatonic stupor

delusion: belief that is contrary to reality and is firmly held, despite contradictory evidence

disorganized/abnormal motor behavior: highly unusual behaviors and movements (such as child-like behaviors), repeated and purposeless movements, and displaying odd facial expressions and gestures

disorganized thinking: disjointed and incoherent thought processes, usually detected by what a person says

dopamine hypothesis: theory of schizophrenia that proposes that an overabundance of dopamine or dopamine receptors is responsible for the onset and maintenance of schizophrenia

grandiose delusion: characterized by beliefs that one holds special power, unique knowledge, or is extremely important

hallucination: a perceptual experience that occurs in the absence of external stimulation, such as the auditory hallucinations (hearing voices) common to schizophrenia

negative symptom: characterized by decreases and absences in certain normal behaviors, emotions, or drives, such as an expressionless face, lack of motivation to engage in activities, reduced speech, lack of social engagement, and inability to experience pleasure

paranoid delusion: characterized by beliefs that others are out to harm them

prodromal symptom: in schizophrenia, one of the early minor symptoms of psychosis

schizophrenia: a severe disorder characterized by major disturbances in thought, perception, emotion, and behavior with symptoms that include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking and behavior, and negative symptoms

somatic delusion: belief that something highly unusual is happening to one’s body or internal organs

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Anton Tolman for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Wallis Back for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Schizophrenia. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@5.52:gGD_wNTe@5/Schizophrenia. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

- Information on positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Provided by: Boundless. Located at: https://www.boundless.com/psychology/textbooks/boundless-psychology-textbook/psychological-disorders-18/schizophrenia-spectrum-and-other-psychotic-disorders-94/introduction-to-schizophrenia-and-psychosis-360-12895/. Project: Boundless Psychology. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tactile hallucination image. Authored by: Angela Mariam Thomas. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tactile_hallucination.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Schizophrenia lobes picture. Authored by: BruceBlaus. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schizophrenia_(Brain).png. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Schizophrenia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schizophrenia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders . Authored by: Deanna M. Barch . Provided by: Washington University in St. Louis. Located at: https://nobaproject.com/modules/schizophrenia-spectrum-disorders. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Schizophrenia causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment & pathology. Provided by: Osmosis. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PURvJV2SMso. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Provided by: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Located at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519704/table/ch3.t22/. Project: SAMHSA. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Schizophrenia. Provided by: NIMH. Located at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia/index.shtml. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Vita, A. & Barlati, S. (2018). Recovery from Schizophrenia: Is it possible? Current Opinion Psychiatry, 31(3), 246-255. DOI: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000407 ↵

- Publishing, Harvard Health. “The Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia.” Harvard Health. Accessed December 31, 2020. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mental-health/the-negative-symptoms-of-schizophrenia. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Impact of the DSM-IV to DSM-5 Changes on the National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2016 Jun. Table 3.22, DSM-IV to DSM-5 Schizophrenia Comparison. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519704/table/ch3.t22 ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Publisher. ↵