Learning Outcomes

- Identify characteristics of birds

Birds are endothermic, and more specifically, homeothermic—meaning that they usually maintain an elevated and constant body temperature, which is significantly above the average body temperature of most mammals. This is, in part, due to the fact that active flight—especially the hovering skills of birds such as hummingbirds—requires enormous amounts of energy, which in turn necessitates a high metabolic rate. Like mammals (which are also endothermic and homeothermic and covered with an insulating pelage), birds have several different types of feathers that together keep “heat” (infrared energy) within the core of the body, away from the surface where it can be lost by radiation and convection to the environment.

Modern birds produce two main types of feathers: contour feathers and down feathers. Contour feathers have a number of parallel barbs that branch from a central shaft. The barbs in turn have microscopic branches called barbules that are linked together by minute hooks, making the vane of a feather a strong, flexible, and uninterrupted surface. In contrast, the barbules of down feathers do not interlock, making these feathers especially good for insulation, trapping air in spaces between the loose, interlocking barbules of adjacent feathers to decrease the rate of heat loss by convection and radiation. Certain parts of a bird’s body are covered in down feathers, and the base of other feathers has a downy portion, whereas newly hatched birds are covered almost entirely in down, which serves as an excellent coat of insulation, increasing the thermal boundary layer between the skin and the outside environment.

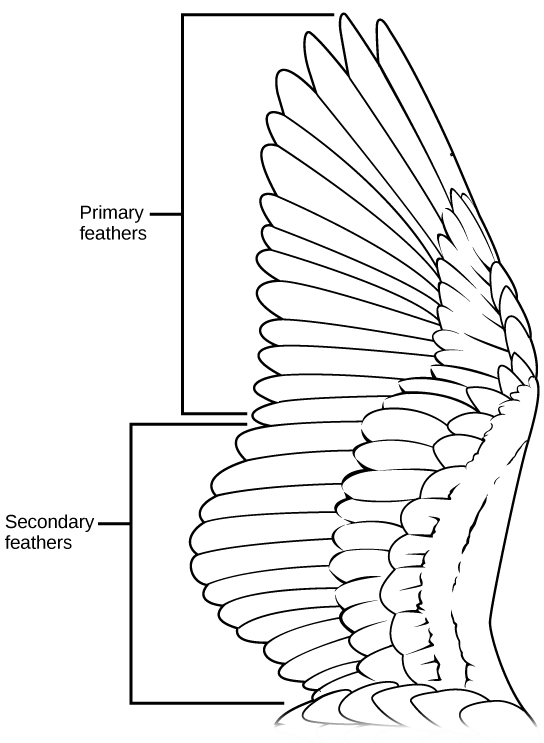

Figure 1. Primary feathers are located at the wing tip and provide thrust; secondary feathers are located close to the body and provide lift.

Feathers not only provide insulation, but also allow for flight, producing the lift and thrust necessary for flying birds to become and stay airborne. The feathers on a wing are flexible, so the feathers at the end of the wing separate as air moves over them, reducing the drag on the wing. Flight feathers are also asymmetrical and curved, so that air flowing over them generates lift. Two types of flight feathers are found on the wings, primary feathers and secondary feathers (Figure 1). Primary feathers are located at the tip of the wing and provide thrust as the bird moves its wings downward, using the pectoralis major muscles. Secondary feathers are located closer to the body, in the forearm portion of the wing, and provide lift. In contrast to primary and secondary feathers, contour feathers are found on the body, where they help reduce form drag produced by wind resistance against the body during flight. They create a smooth, aerodynamic surface so that air moves swiftly over the bird’s body, preventing turbulence and creating ideal aerodynamic conditions for efficient flight.

Flapping of the entire wing occurs primarily through the actions of the chest muscles: Specifically, the contraction of the pectoralis major muscles moves the wings downward (downstroke), whereas contraction of the supracoracoideus muscles moves the wings upward (upstroke) via a tough tendon that passes over the coracoid bone and the top of the humerus. Both muscles are attached to the keel of the sternum, and these are the muscles that humans eat on holidays (this is why the back of the bird offers little meat!). These muscles are highly developed in birds and account for a higher percentage of body mass than in most mammals. The flight muscles attach to a blade-shaped keel projecting ventrally from the sternum, like the keel of a boat. The sternum of birds is deeper than that of other vertebrates, which accommodates the large flight muscles. The flight muscles of birds who are active flyers are rich with oxygen-storing myoglobin. Another skeletal modification found in most birds is the fusion of the two clavicles (collarbones), forming the furcula or wishbone. The furcula is flexible enough to bend and provide support to the shoulder girdle during flapping.

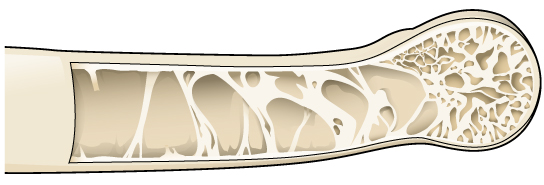

An important requirement for flight is a low body weight. As body weight increases, the muscle output required for flying increases. The largest living bird is the ostrich, and while it is much smaller than the largest mammals, it is secondarily flightless. For birds that do fly, reduction in body weight makes flight easier. Several modifications are found in birds to reduce body weight, including pneumatization of bones. Pneumatic bones (Figure 2) are bones that are hollow, rather than filled with tissue; cross struts of bone called trabeculae provide structural reinforcement. Pneumatic bones are not found in all birds, and they are more extensive in large birds than in small birds. Not all bones of the skeleton are pneumatic, although the skulls of almost all birds are. The jaw is also lightened by the replacement of heavy jawbones and teeth with a beak made of keratin (just as hair, scales, and feathers are).

Figure 2. Many birds have hollow, pneumatic bones, which make flight easier.

Other modifications that reduce weight include the lack of a urinary bladder. Birds possess a cloaca, an external body cavity into which the intestinal, urinary, and genital orifices empty in reptiles, birds, and the monotreme mammals. The cloaca allows water to be reabsorbed from waste back into the bloodstream. Thus, uric acid is not eliminated as a liquid but is concentrated into urate salts, which are expelled along with fecal matter. In this way, water is not held in a urinary bladder, which would increase body weight. In addition, the females of most bird species only possess one functional (left) ovary rather than two, further reducing body mass.

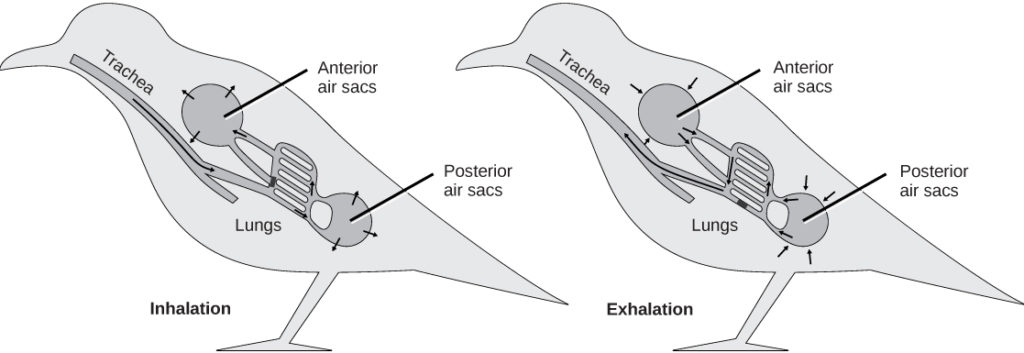

The respiratory system of birds is dramatically different from that of reptiles and mammals, and is well adapted for the high metabolic rate required for flight. To begin, the air spaces of pneumatic bone are sometimes connected to air sacs in the body cavity, which replace coelomic fluid and also lighten the body. These air sacs are also connected to the path of airflow through the bird’s body, and function in respiration. Unlike mammalian lungs in which air flows in two directions, as it is breathed in and out, diluting the concentration of oxygen, airflow through bird lungs is unidirectional (Figure 3). Gas exchange occurs in “air capillaries” or microscopic air passages within the lungs. The arrangement of air capillaries in the lungs creates a counter-current exchange system with the pulmonary blood. In a counter-current system, the air flows in one direction and the blood flows in the opposite direction, producing a favorable diffusion gradient and creating an efficient means of gas exchange. This very effective oxygen-delivery system of birds supports their higher metabolic activity. In effect, ventilation is provided by the parabronchi (minimally expandible lungs) with thin air sacs located among the visceral organs and the skeleton. A syrinx (voice box) resides near the junction of the trachea and bronchi. The syrinx, however, is not homologous to the mammalian larynx, which resides within the upper part of the trachea.

Figure 3. Avian respiration is an efficient system of gas exchange with air flowing unidirectionally. During inhalation, air passes from the trachea into posterior air sacs, then through the lungs to anterior air sacs. The air sacs are connected to the hollow interior of bones. During exhalation, air from air sacs passes into the lungs and out the trachea. (credit: modification of work by L. Shyamal)

Beyond the unique characteristics discussed above, birds are also unusual vertebrates because of a number of other features. First, they typically have an elongate (very “dinosaurian”) S-shaped neck, but a short tail or pygostyle, produced from the fusion of the caudal vertebrae. Unlike mammals, birds have only one occipital condyle, allowing them extensive movement of the head and neck. They also have a very thin epidermis without sweat glands, and a specialized uropygial gland or sebaceous “preening gland” found at the dorsal base of the tail. This gland is an essential to preening (a virtually continuous activity) in most birds because it produces an oily substance that birds use to help waterproof their feathers as well as keep them flexible for flight. A number of birds, such as pigeons, parrots, hawks, and owls, lack a uropygial gland but have specialized feathers that “disintegrate” into a powdery down, which serves the same purpose as the oils of the uropygial gland.

Like mammals, birds have 12 pairs of cranial nerves, and a very large cerebellum and optic lobes, but only a single bone in the middle ear called the columella (the stapes in mammals). They have a closed circulatory system with two atria and two ventricles, but rather than a “left-bending” aortic arch like that of mammals, they have a “right-bending” aortic arch, and nucleated red blood cells (unlike the enucleated red blood cells of mammals).

All these unique and highly derived characteristics make birds one of the most conspicuous and successful groups of vertebrate animals, filling a range of ecological niches, and ranging in size from the tiny bee hummingbird of Cuba (about 2 grams) to the ostrich (about 140,000 grams). Their large brains, keen senses, and the abilities of many species to imitate vocalization and use tools make them some of the most intelligent vertebrates on Earth.

In Summary: Characteristics of Birds

Birds are endothermic, meaning they produce their own body heat and regulate their internal temperature independently of the external temperature. Feathers not only act as insulation but also allow for flight, providing lift with secondary feathers and thrust with primary feathers. Pneumatic bones are bones that are hollow rather than filled with tissue, containing air spaces that are sometimes connected to air sacs. Airflow through bird lungs travels in one direction, creating a cross-current exchange with the blood.

Try It

Candela Citations

- Biology 2e. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction