Learning Outcomes

- Identify different types of learned behaviors in animals

Simple Learned Behaviors

The majority of the behaviors previously discussed were innate or at least have an innate component (variations on the innate behaviors may be learned). They are inherited and the behaviors do not change in response to signals from the environment. Conversely, learned behaviors, even though they may have instinctive components, allow an organism to adapt to changes in the environment and are modified by previous experiences. Simple learned behaviors include habituation and imprinting—both are important to the maturation process of young animals.

Habituation

Habituation is a simple form of learning in which an animal stops responding to a stimulus after a period of repeated exposure. This is a form of non-associative learning, as the stimulus is not associated with any punishment or reward. Prairie dogs typically sound an alarm call when threatened by a predator, but they become habituated to the sound of human footsteps when no harm is associated with this sound, therefore, they no longer respond to them with an alarm call. In this example, habituation is specific to the sound of human footsteps, as the animals still respond to the sounds of potential predators.

Imprinting

Figure 1. The attachment of ducklings to their mother is an example of imprinting. (credit: modification of work by Mark Harkin)

Imprinting is a type of learning that occurs at a particular age or a life stage that is rapid and independent of the species involved. Hatchling ducks recognize the first adult they see, their mother, and make a bond with her. A familiar sight is ducklings walking or swimming after their mothers (Figure 1). This is another type of non-associative learning, but is very important in the maturation process of these animals as it encourages them to stay near their mother so they will be protected, greatly increasing their chances of survival. However, if newborn ducks see a human before they see their mother, they will imprint on the human and follow it in just the same manner as they would follow their real mother.

The International Crane Foundation has helped raise the world’s population of whooping cranes from 21 individuals to about 600. Imprinting hatchlings has been a key to success: biologists wear full crane costumes so the birds never “see” humans. Watch this video to learn more.

Conditioned Behavior

Conditioned behaviors are types of associative learning, where a stimulus becomes associated with a consequence. During operant conditioning, the behavioral response is modified by its consequences, with regards to its form, strength, or frequency.

Classical Conditioning

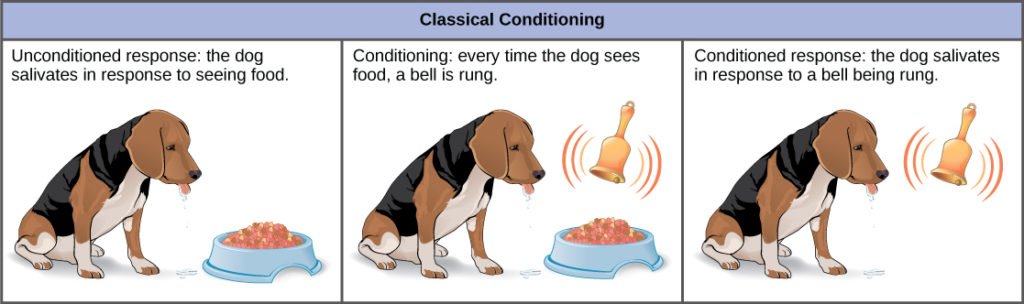

In classical conditioning, a response called the conditioned response is associated with a stimulus that it had previously not been associated with, the conditioned stimulus. The response to the original, unconditioned stimulus is called the unconditioned response. The most cited example of classical conditioning is Ivan Pavlov’s experiments with dogs (Figure 2). In Pavlov’s experiments, the unconditioned response was the salivation of dogs in response to the unconditioned stimulus of seeing or smelling their food. The conditioning stimulus that researchers associated with the unconditioned response was the ringing of a bell. During conditioning, every time the animal was given food, the bell was rung. This was repeated during several trials. After some time, the dog learned to associate the ringing of the bell with food and to respond by salivating. After the conditioning period was finished, the dog would respond by salivating when the bell was rung, even when the unconditioned stimulus, the food, was absent. Thus, the ringing of the bell became the conditioned stimulus and the salivation became the conditioned response. Although it is thought by some scientists that the unconditioned and conditioned responses are identical, even Pavlov discovered that the saliva in the conditioned dogs had characteristic differences when compared to the unconditioned dog.

Figure 2. In the classic Pavlovian response, the dog becomes conditioned to associate the ringing of the bell with food.

It had been thought by some scientists that this type of conditioning required multiple exposures to the paired stimulus and response, but it is now known that this is not necessary in all cases, and that some conditioning can be learned in a single pairing experiment. Classical conditioning is a major tenet of behaviorism, a branch of psychological philosophy that proposes that all actions, thoughts, and emotions of living things are behaviors that can be treated by behavior modification and changes in the environment.

Operant Conditioning

Figure 3. The training of dolphins by rewarding them with food is an example of positive reinforcement operant conditioning. (credit: Roland Tanglao)

In operant conditioning, the conditioned behavior is gradually modified by its consequences as the animal responds to the stimulus. A major proponent of such conditioning was psychologist B.F. Skinner, the inventor of the Skinner box. Skinner put rats in his boxes that contained a lever that would dispense food to the rat when depressed. While initially the rat would push the lever a few times by accident, it eventually associated pushing the lever with getting the food. This type of learning is an example of operant conditioning. Operant learning is the basis of most animal training. The conditioned behavior is continually modified by positive or negative reinforcement, often a reward such as food or some type of punishment, respectively. In this way, the animal is conditioned to associate a type of behavior with the punishment or reward, and, over time, can be induced to perform behaviors that they would not have done in the wild, such as the “tricks” dolphins perform at marine amusement park shows (Figure 3).

Cognitive Learning

Classical and operant conditioning are inefficient ways for humans and other intelligent animals to learn. Some primates, including humans, are able to learn by imitating the behavior of others and by taking instructions. The development of complex language by humans has made cognitive learning, the manipulation of information using the mind, the most prominent method of human learning. In fact, that is how students are learning right now by reading this book. As students read, they can make mental images of objects or organisms and imagine changes to them, or behaviors by them, and anticipate the consequences. In addition to visual processing, cognitive learning is also enhanced by remembering past experiences, touching physical objects, hearing sounds, tasting food, and a variety of other sensory-based inputs. Cognitive learning is so powerful that it can be used to understand conditioning in detail. In the reverse scenario, conditioning cannot help someone learn about cognition.

Classic work on cognitive learning was done by Wolfgang Köhler with chimpanzees. He demonstrated that these animals were capable of abstract thought by showing that they could learn how to solve a puzzle. When a banana was hung in their cage too high for them to reach, and several boxes were placed randomly on the floor, some of the chimps were able to stack the boxes one on top of the other, climb on top of them, and get the banana. This implies that they could visualize the result of stacking the boxes even before they had performed the action. This type of learning is much more powerful and versatile than conditioning.

Cognitive learning is not limited to primates, although they are the most efficient in using it. Maze running experiments done with rats by H.C. Blodgett in the 1920s were the first to show cognitive skills in a simple mammal. The motivation for the animals to work their way through the maze was a piece of food at its end. In these studies, the animals in Group I were run in one trial per day and had food available to them each day on completion of the run (Figure 4). Group II rats were not fed in the maze for the first six days and then subsequent runs were done with food for several days after. Group III rats had food available on the third day and every day thereafter. The results were that the control rats, Group I, learned quickly, and figured out how to run the maze in seven days. Group III did not learn much during the three days without food, but rapidly caught up to the control group when given the food reward. Group II learned very slowly for the six days with no reward to motivate them, and they did not begin to catch up to the control group until the day food was given, and then it took two days longer to learn the maze.

Figure 4. Group I (the green solid line) found food at the end of each trial, group II (the blue dashed line) did not find food for the first 6 days, and group III (the red dotted line) did not find food during runs on the first three days. Notice that rats given food earlier learned faster and eventually caught up to the control group. The orange dots on the group II and III lines show the days when food rewards were added to the mazes.

It may not be immediately obvious that this type of learning is different than conditioning. Although one might be tempted to believe that the rats simply learned how to find their way through a conditioned series of right and left turns, E.C. Tolman proved a decade later that the rats were making a representation of the maze in their minds, which he called a “cognitive map.” This was an early demonstration of the power of cognitive learning and how these abilities were not just limited to humans.

Sociobiology

Sociobiology is an interdisciplinary science originally popularized by social insect researcher E.O. Wilson in the 1970s. Wilson defined the science as “the extension of population biology and evolutionary theory to social organization.”[1] The main thrust of sociobiology is that animal and human behavior, including aggressiveness and other social interactions, can be explained almost solely in terms of genetics and natural selection. This science is controversial; noted scientist such as the late Stephen Jay Gould criticized the approach for ignoring the environmental effects on behavior. This is another example of the “nature versus nurture” debate of the role of genetics versus the role of environment in determining an organism’s characteristics.

Sociobiology also links genes with behaviors and has been associated with “biological determinism,” the belief that all behaviors are hardwired into our genes. No one disputes that certain behaviors can be inherited and that natural selection plays a role retaining them. It is the application of such principles to human behavior that sparks this controversy, which remains active today.

Try It

Candela Citations

- Biology 2e. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Edward O. Wilson. On Human Nature (1978; repr., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), xx. ↵