LEARNING Outcomes

- Identify the domain of a logarithmic function

- Graph logarithmic functions

Before working with graphs, we will take a look at the domain (the set of input values) for which the logarithmic function is defined.

Recall that the exponential function is defined as [latex]y={b}^{x}[/latex] for any real number x and constant [latex]b>0[/latex], [latex]b\ne 1[/latex], where

- The domain of is [latex]\left(-\infty ,\infty \right)[/latex].

- The range of is [latex]\left(0,\infty \right)[/latex].

In the last section we learned that the logarithmic function [latex]y={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex] is the inverse of the exponential function [latex]y={b}^{x}[/latex]. So, as inverse functions:

- The domain of [latex]y={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex] is the range of [latex]y={b}^{x}[/latex]: [latex]\left(0,\infty \right)[/latex].

- The range of [latex]y={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex] is the domain of [latex]y={b}^{x}[/latex]: [latex]\left(-\infty ,\infty \right)[/latex].

Therefore, when finding the domain of a logarithmic function, it is important to remember that the domain consists only of positive real numbers. That is, the value you are applying the logarithmic function to, also known as the argument of the logarithmic function, must be greater than zero.

For example, consider [latex]y={\mathrm{log}}_{4}\left(2x-3\right)[/latex]. This function is defined for any values of x such that the argument, in this case [latex]2x-3[/latex], is greater than zero. To find the domain, we set up an inequality and solve for x:

[latex]\begin{array}{c}2x-3>0\hfill & \text{The argument must be positive}.\hfill \\ 2x>3\hfill & \text{Add 3}.\hfill \\ x>1.5\hfill & \text{Divide by 2}.\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

In interval notation, the domain of [latex]f\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{4}\left(2x-3\right)[/latex] is [latex]\left(1.5,\infty \right)[/latex].

How To: Given a logarithmic function, identify the domain

- Set up an inequality showing the argument greater than zero.

- Solve for x.

- Write the domain in interval notation.

In our first example, we will show how to identify the domain of a logarithmic function.

Example

What is the domain of [latex]f\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(x+3\right)[/latex]?

Here is another example of how to identify the domain of a logarithmic function.

Example

What is the domain of [latex]f\left(x\right)=\mathrm{log}\left(5 - 2x\right)[/latex]?

Graph Logarithmic Functions

Creating a graphical representation of most functions gives us another layer of insight for predicting future events. How do logarithmic graphs give us insight into situations? Because every logarithmic function is the inverse function of an exponential function, we can think of every output on a logarithmic graph as the input for the corresponding inverse exponential equation. In other words, logarithms give the cause for an effect.

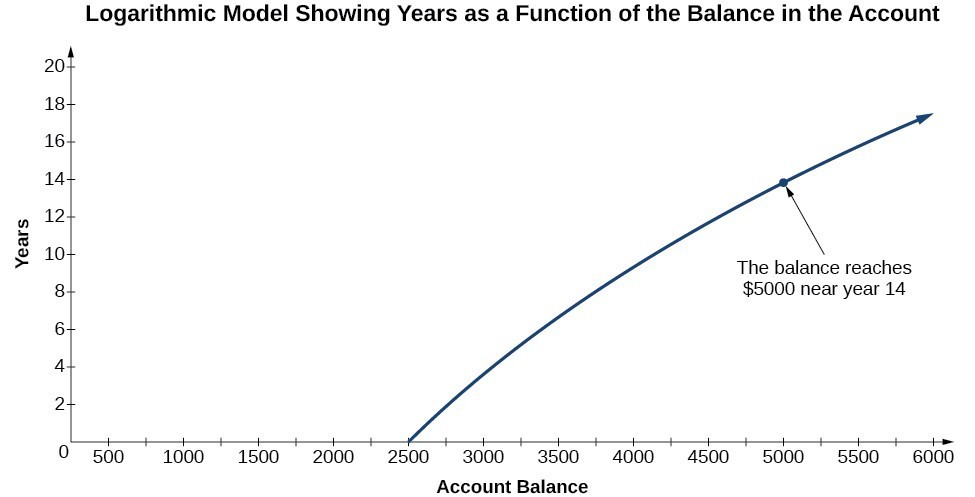

To illustrate, suppose we invest $2500 in an account that offers an annual interest rate of [latex]5\%[/latex], compounded continuously. We already know that the balance in our account for any year t can be found with the equation [latex]A=2500{e}^{0.05t}[/latex].

But what if we wanted to know the year for any balance? We would need to create a corresponding new function by interchanging the input and the output; thus we would need to create a logarithmic model for this situation. By graphing the model, we can see the output (year) for any input (account balance). For instance, what if we wanted to know how many years it would take for our initial investment to double? The image below shows this point on the logarithmic graph.

A logarithmic graph showing how many years it will take for an account balance to double.

Now that we have a feel for the set of values for which a logarithmic function is defined, we move on to graphing logarithmic functions. The family of logarithmic functions includes the parent function [latex]y={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex] along with all its transformations: shifts, stretches, compressions, and reflections.

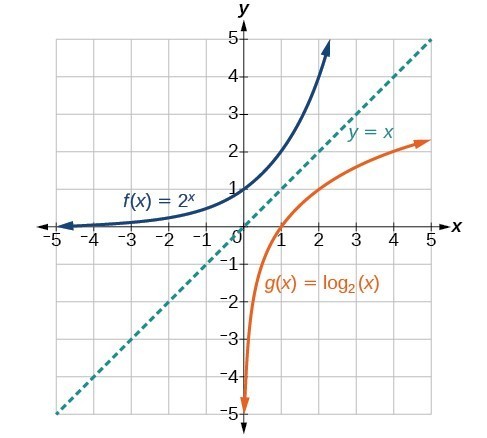

We begin with the parent function [latex]y={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex]. Because every logarithmic function of this form is the inverse of an exponential function of the form [latex]y={b}^{x}[/latex], their graphs will be reflections of each other across the line [latex]y=x[/latex]. To illustrate this, we can observe the relationship between the input and output values of [latex]y={2}^{x}[/latex] and its equivalent [latex]x={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(y\right)[/latex] in the table below.

| x | [latex]–3[/latex] | [latex]–2[/latex] | [latex]–1[/latex] | [latex]0[/latex] | [latex]1[/latex] | [latex]2[/latex] | [latex]3[/latex] |

| [latex]{2}^{x}=y[/latex] | [latex]\frac{1}{8}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{1}{4}[/latex] | [latex]\frac{1}{2}[/latex] | [latex]1[/latex] | [latex]2[/latex] | [latex]4[/latex] | [latex]8[/latex] |

| [latex]{\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(y\right)=x[/latex] | [latex]–3[/latex] | [latex]–2[/latex] | [latex]–1[/latex] | [latex]0[/latex] | [latex]1[/latex] | [latex]2[/latex] | [latex]3[/latex] |

Using the inputs and outputs from the table above, we can build another table to observe the relationship between points on the graphs of the inverse functions [latex]f\left(x\right)={2}^{x}[/latex] and [latex]g\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(x\right)[/latex].

| [latex]f\left(x\right)={2}^{x}[/latex] | [latex]\left(-3,\frac{1}{8}\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(-2,\frac{1}{4}\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(-1,\frac{1}{2}\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(0,1\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(1,2\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(2,4\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(3,8\right)[/latex] |

| [latex]g\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(x\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(\frac{1}{8},-3\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(\frac{1}{4},-2\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(\frac{1}{2},-1\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(1,0\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(2,1\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(4,2\right)[/latex] | [latex]\left(8,3\right)[/latex] |

As we would expect, the x– and y-coordinates are reversed for the inverse functions. The figure below shows the graph of f and g.

Notice that the graphs of [latex]f\left(x\right)={2}^{x}[/latex] and [latex]g\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(x\right)[/latex] are reflections about the line y = x. This is a special property of the relationship between any function and its inverse.

Observe the following from the graph:

- [latex]f\left(x\right)={2}^{x}[/latex] has a y-intercept at [latex]\left(0,1\right)[/latex] and [latex]g\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(x\right)[/latex] has an x-intercept at [latex]\left(1,0\right)[/latex].

- The domain of [latex]f\left(x\right)={2}^{x}[/latex], [latex]\left(-\infty ,\infty \right)[/latex], is the same as the range of [latex]g\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(x\right)[/latex].

- The range of [latex]f\left(x\right)={2}^{x}[/latex], [latex]\left(0,\infty \right)[/latex], is the same as the domain of [latex]g\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(x\right)[/latex].

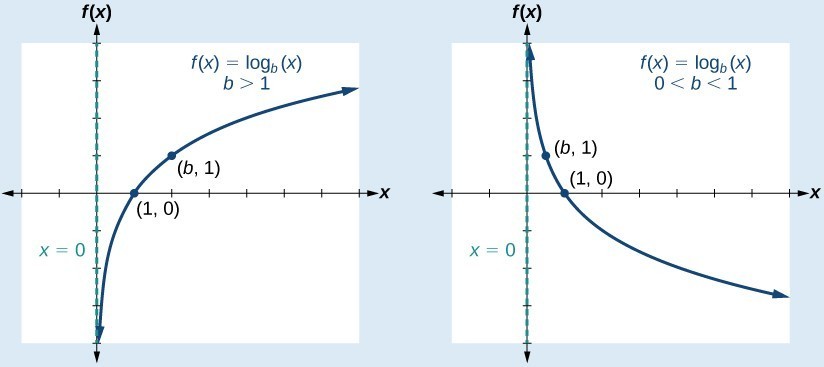

A General Note: Characteristics of the Graph of the Parent Function, f(x) = logb(x)

For any real number x and constant b > 0, [latex]b\ne 1[/latex], we can see the following characteristics in the graph of [latex]f\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex]:

- one-to-one function

- vertical asymptote: x =[latex]0[/latex]

- domain: [latex]\left(0,\infty \right)[/latex]

- range: [latex]\left(-\infty ,\infty \right)[/latex]

- x-intercept: [latex]\left(1,0\right)[/latex] and key point [latex]\left(b,1\right)[/latex]

- y-intercept: none

- increasing if [latex]b>1[/latex]

- decreasing if [latex]0 \lt b \lt 1[/latex]

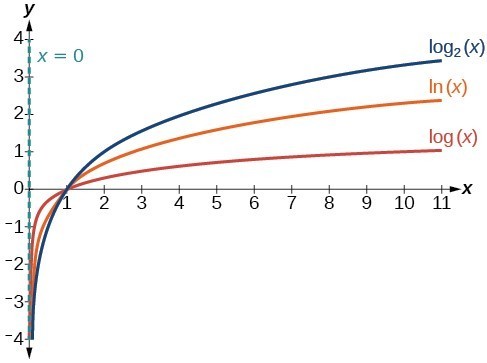

The figure below shows how changing the base b in [latex]f\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex] can affect the graphs. Observe that the graphs compress vertically as the value of the base increases. (Note: recall that the function [latex]\mathrm{ln}\left(x\right)[/latex] has base [latex]e\approx \text{2}.\text{718.)}[/latex]

The graphs of three logarithmic functions with different bases, all greater than 1.

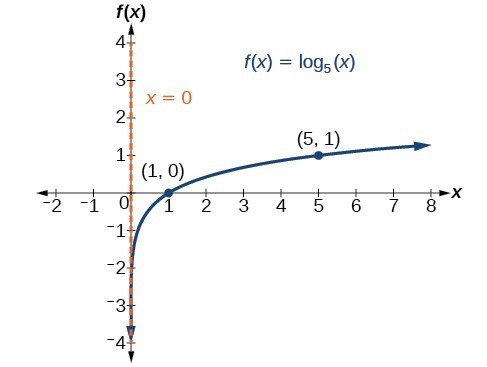

In our next example, we will graph a logarithmic function of the form [latex]f\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex].

Example

Graph [latex]f\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{5}\left(x\right)[/latex]. State the domain and range.

How To: Given a logarithmic function of the form [latex]f\left(x\right)={\mathrm{log}}_{b}\left(x\right)[/latex], graph the function

- Plot the x-intercept, [latex]\left(1,0\right)[/latex].

- Plot the key point [latex]\left(b,1\right)[/latex].

- Draw a smooth curve through the points.

- State the domain, [latex]\left(0,\infty \right)[/latex], and the range, [latex]\left(-\infty ,\infty \right)[/latex].

Summary

To define the domain of a logarithmic function algebraically, set the argument greater than zero and solve. To plot a logarithmic function, it is easiest to find and plot the x-intercept and the key point [latex]\left(b,1\right)[/latex].