Learning Objectives

Identify characteristic structuring principles in poetry

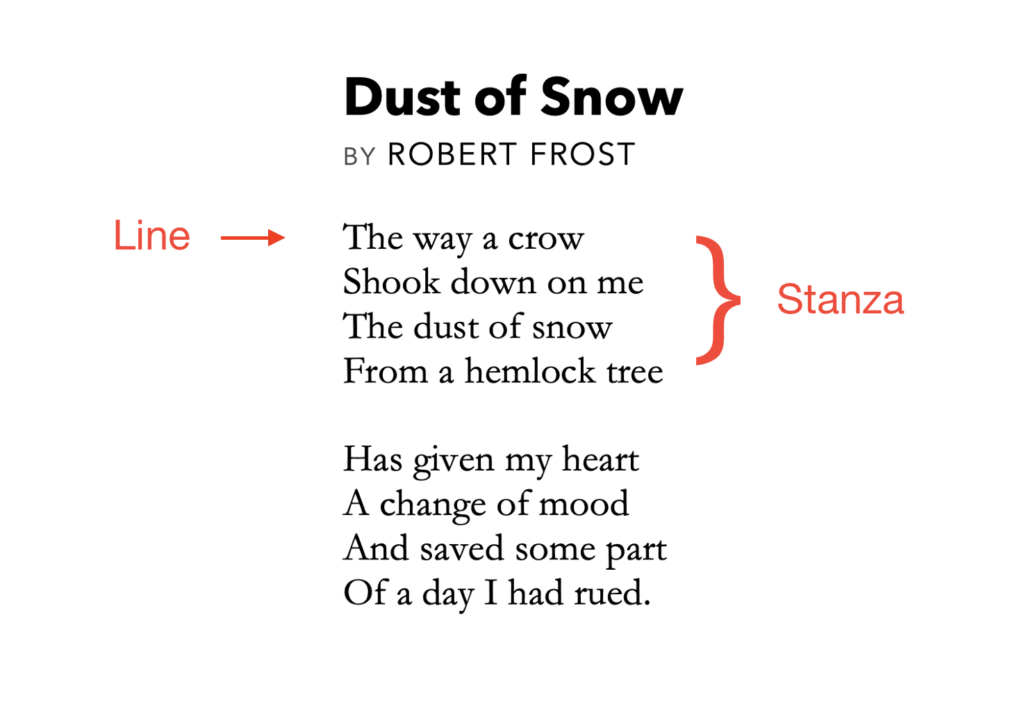

In the figure above, you will find eight lines and two stanzas. A line is a single row of words in a poem. A group of lines builds a stanza, which typically focuses on one thought, concept, or portion of a story. Stanzas are typically separated by extra space or a blank line. To draw a parallel to prose, one might think of poetry’s lines as sentences, and of its stanzas as paragraphs.

The words and syllables in a poem also play a key role in forming its structure. Poets frequently use rhyme, meaning that they choose words that contain corresponding sounds (ex: cat, hat, bat), which often appear at the ends of lines. Rhyming can add to the beauty of a poem by creating a pleasurable echo among lines. It also helps build the poem’s structure by unifying the lines so that they sound right together. A common misconception, however, is that all poems rhyme. Many do not follow a rhyme scheme, as we can see in examples like Maya Angelou’s “Caged Bird” and T.S. Eliot’s “Aunt Helen.” Rhyme is just one tool that poets might use to create their art, but it is not a required element.

Poets can also use meter to create aesthetic and structure in their work. “Meter” refers to the rhythm of a line, which depends on the number of syllables, and on the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in the line.

In following video from Oregon State University, pay attention to the difference between stressed and unstressed syllables:

As we can see, syllabic stress plays a major role in how we understand words in English. Consider the word “present.” You may have read that word as gift one receives for an occasion, or as current moment in time, in relation to “past” and “future.” If so, you placed the stress on the first syllable (PREH-zent). You may, however, have read the word as a verb that refers to the act of giving an award to someone. If so, you placed the stress on the second syllable (pre-ZENT). If you’re familiar with languages like Spanish, it may be helpful to think about the letters over which we place accent marks (habló vs. hablo). These accent marks indicate that a syllable should be stressed.

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a poem helps create a rhythm that readers can follow, much like the beat in a song. One can determine the meter by analyzing this pattern of syllables, which can be broken into “feet.” A foot refers to a group of syllables in a poem. A foot usually contains one stressed syllable and at least one unstressed syllable. The five most common types of feet are as follows, with “U” representing unstressed syllables, and “S” representing stressed syllables:

- trochee (S+U)

- iamb (U+S)

- dactyl (S+U+U)

- anapest (U+U+S)

- spondee (S+S)

Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven” is an example of trochaic meter (using trochees). The first line is highlighted to reflect the syllables in each trochee. The syllables that are highlighted in green are stressed, while those in blue are unstressed:

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Lord Byron’s “She Walks in Beauty” is an example of iambic meter (using iambs). Like the previous example, syllables that are highlighted in green are stressed, while those in blue are unstressed:

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes;

Thus mellowed to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

Both trochaic and iambic meters alternate between stressed and unstressed syllables, but the difference is the order in which they appear. In the examples above, Poe’s lines begin with stressed syllables, while Byron’s begin with unstressed ones.

The number of feet in a line also contributes to how we identify meter. If you have heard of “iambic pentameter” before, you have already encountered this type of identification. The first word refers to the stress patterns in the poem’s feet, while the second word refers to how many feet are in each line.

- one foot = monometer

- two feet = dimeter

- three feet = trimeter

- four feet = tetrameter

- five feet = pentameter

- six feet = hexameter

- seven feet = heptameter

- eight feet = octameter

So, if we look again at iambic pentameter, which is quite common in Shakespeare’s work, we know that the poem’s feet are iambs (U+S), and that there are five feet per line.

Just like rhyme, meter is a common tool that poets use to create structure, but some poems do not use it. When a poet writes without rhyme or meter, the poem is written in free verse. Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” is an example of a free verse poem.

Try It

Candela Citations

- What is Meter in Poetry?: A Literary Guide for English Students and Teachers. Authored by: OSU Writing, Literature and Film. Provided by: Oregon State University. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S13Tg3RAUW4. License: All Rights Reserved

- Dust of Snow. Authored by: Robert Frost. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Poetic Structure. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution