Learning Outcomes

- Compare inductive reasoning with deductive reasoning

- Describe the process of scientific inquiry

One thing is common to all forms of science: an ultimate goal “to know.” Curiosity and inquiry are the driving forces for the development of science. Scientists seek to understand the world and the way it operates. Two methods of logical thinking are used: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that analyzes trends or relationships in data to arrive at a general conclusion. A scientist makes observations and records them. These data can be qualitative (descriptive) or quantitative (consisting of numbers), and the raw data can be supplemented with drawings, pictures, photos, or videos. From many observations, a scientist can draw conclusions based on evidence. In other words, inductive reasoning involves making generalizations from careful observation and the analysis of a large amount of individual data points. Generalizations arrived at through inductive reasoning are not always correct.

Deductive reasoning is another form of logical thinking that begins from a general principle or law and applies it to a specific circumstance to predict specific results. From a set of general principles, a scientist can extrapolate and predict specific results that will always be correct as long as the general principles they start from are correct.

Deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning move in opposite directions – inductive reasoning goes from individual observations to broad generalizations while deductive reasoning goes from general principles to specific decisions or predictions.

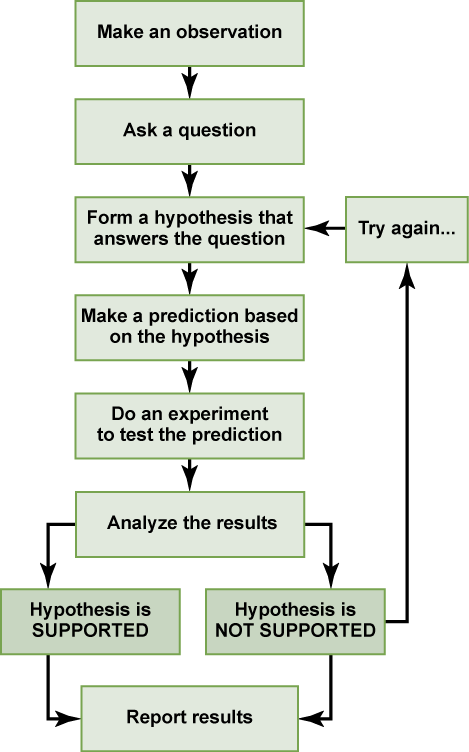

Both types of logical thinking are related to the two main pathways of scientific study: descriptive science and hypothesis-based science. Descriptive science (or discovery science) aims to observe, explore, and discover, while hypothesis-based science begins with a specific question or problem and a potential answer or solution that can be tested. Inductive reasoning is used most often in descriptive science, while deductive reasoning is used most often in hypothesis-based science. The boundary between these two forms of study is often blurred, because most scientific endeavors combine both approaches. Observations lead to questions, questions lead to forming a hypothesis as a possible answer to those questions, and then the hypothesis is tested. Thus, descriptive science and hypothesis-based science are in continuous dialogue.

Hypothesis Testing

Figure 1. Sir Francis Bacon is credited with being the first to document the scientific method.

Biologists study the living world by posing questions about it and seeking science-based responses. This approach is common to other sciences as well and is often referred to as the scientific method. The scientific method was used even in ancient times, but it was first documented by England’s Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) (Figure 1), who set up inductive methods for scientific inquiry. The scientific method is not exclusively used by biologists but can be applied to almost anything as a logical problem-solving method.

The scientific process typically starts with an observation (often a problem to be solved) that leads to a question. Let’s think about a simple problem that starts with an observation and apply the scientific method to solve the problem. One Monday morning, a student arrives at class and quickly discovers that the classroom is too warm. That is an observation that also describes a problem: the classroom is too warm. The student then asks a question: “Why is the classroom so warm?”

Recall that a hypothesis is a suggested explanation that can be tested. To solve a problem, several hypotheses may be proposed. For example, one hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because no one turned on the air conditioning.” But there could be other responses to the question, and therefore other hypotheses may be proposed. A second hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because there is a power failure, and so the air conditioning doesn’t work.”

Once a hypothesis has been selected, a prediction may be made. A prediction is similar to a hypothesis but it typically has the format “If . . . then . . . .” For example, the prediction for the first hypothesis might be, “If the student turns on the air conditioning, then the classroom will no longer be too warm.”

A hypothesis must be testable to ensure that it is valid. For example, a hypothesis that depends on what a bear thinks is not testable, because it can never be known what a bear thinks. It should also be falsifiable, meaning that it can be disproven by experimental results. An example of an unfalsifiable hypothesis is “Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is beautiful.” There is no experiment that might show this statement to be false. To test a hypothesis, a researcher will conduct one or more experiments designed to eliminate one or more of the hypotheses. This is important. A hypothesis can be disproven, or eliminated, but it can never be proven. Science does not deal in proofs like mathematics. If an experiment fails to disprove a hypothesis, then we find support for that explanation, but this is not to say that down the road a better explanation will not be found, or a more carefully designed experiment will be found to falsify the hypothesis.

Scientific inquiry has not displaced faith, intuition, and dreams. These traditions and ways of knowing have emotional value and provide moral guidance to many people. But hunches, feelings, deep convictions, old traditions, or dreams cannot be accepted directly as scientifically valid. Instead, science limits itself to ideas that can be tested through verifiable observations. Supernatural claims that events are caused by ghosts, devils, God, or other spiritual entities cannot be tested in this way.

Practice Question

Your friend sees this image of a circle of mushrooms and excitedly tells you it was caused by fairies dancing in a circle on the grass the night before. Can your friend’s explanation be studied using the process of science?

Each experiment will have one or more variables and one or more controls. A variable is any part of the experiment that can vary or change during the experiment. A control is a part of the experiment that does not change. Look for the variables and controls in the example that follows. As a simple example, an experiment might be conducted to test the hypothesis that phosphate limits the growth of algae in freshwater ponds. A series of artificial ponds are filled with water and half of them are treated by adding phosphate each week, while the other half are treated by adding a salt that is known not to be used by algae. The variable here is the phosphate (or lack of phosphate), the experimental or treatment cases are the ponds with added phosphate and the control ponds are those with something inert added, such as the salt. Just adding something is also a control against the possibility that adding extra matter to the pond has an effect. If the treated ponds show lesser growth of algae, then we have found support for our hypothesis. If they do not, then we reject our hypothesis. Be aware that rejecting one hypothesis does not determine whether or not the other hypotheses can be accepted; it simply eliminates one hypothesis that is not valid (Figure 2). Using the scientific method, the hypotheses that are inconsistent with experimental data are rejected.

Practice Question

Figure 2. The scientific method is a series of defined steps that include experiments and careful observation. If a hypothesis is not supported by data, a new hypothesis can be proposed.

In the example below, the scientific method is used to solve an everyday problem. Which part in the example below is the hypothesis? Which is the prediction? Based on the results of the experiment, is the hypothesis supported? If it is not supported, propose some alternative hypotheses.

- My toaster doesn’t toast my bread.

- Why doesn’t my toaster work?

- There is something wrong with the electrical outlet.

- If something is wrong with the outlet, my coffeemaker also won’t work when plugged into it.

- I plug my coffeemaker into the outlet.

- My coffeemaker works.

In practice, the scientific method is not as rigid and structured as it might at first appear. Sometimes an experiment leads to conclusions that favor a change in approach; often, an experiment brings entirely new scientific questions to the puzzle. Many times, science does not operate in a linear fashion; instead, scientists continually draw inferences and make generalizations, finding patterns as their research proceeds. Scientific reasoning is more complex than the scientific method alone suggests.

Try It

Try It

Candela Citations

- Concepts of Biology. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/b3c1e1d2-839c-42b0-a314-e119a8aafbdd@9.25. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: http://cnx.org/contents/b3c1e1d2-839c-42b0-a314-e119a8aafbdd@9.25

- Practice Question (Scientific Inquiry). Provided by: Open Learning Initiative. Located at: https://oli.cmu.edu/jcourse/workbook/activity/page?context=434a5c2680020ca6017c03488572e0f8. Project: Introduction to Biology (Open + Free). License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The Process of Science Ch 1.2 Exercisest. Authored by: Charles Molnar and Michelle Nakano. Provided by: BC Campus. Located at: https://opentextbc.ca/biology/h5p-listing/. License: CC BY: Attribution