Learning Objectives

- Discuss the origins and creation of the Whig Party

- Describe the election of 1840 and its outcome

Anti-Masons, Anti-Immigrants, and the Whig Coalition

The Whig coalition drew strength from several earlier parties, including two that harnessed American political paranoia. The Anti-Masonic Party formed in the 1820s for the purpose of destroying the Freemasons. Later, anti-immigrant sentiment formed the American Party, also called the Know-Nothings. The American Party sought and won office across the country in the 1850s, but nativism had already been an influential force, particularly in the Whig Party, whose members could not fail to notice that urban Irish Catholics strongly tended to support Democrats.

Freemasonry

Freemasonry, an international network of social clubs with arcane traditions and rituals, seems to have originated in medieval Europe as a trade organization for stonemasons. By the eighteenth century, however, it had outgrown its relationship with the masons’ craft and had become a general secular fraternal order that proclaimed adherence to the ideals of the Enlightenment.

Freemasonry was an important part of the social life of men in the new republic’s elite. George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Andrew Jackson, and Henry Clay all claimed membership. Prince Hall, a free leather worker in Boston, founded a separate branch of the order for African American men. However, the Masonic brotherhood’s secrecy, elitism, rituals, and secular ideals generated a deep suspicion of the organization among many Americans.

In 1820s upstate New York, which was fertile soil for new religious and social reform movements, anti-Masonic suspicion would emerge for the first time as an organized political force. The trigger for this was the strange disappearance and probable murder of William Morgan. Morgan announced plans to publish an exposé called Illustrations of Masonry. This book purported to reveal the order’s secret rites, and it outraged other local Freemasons. They launched a series of attempts to prevent the book from being published, including an attempt to burn the press and a conspiracy to have Morgan jailed for alleged debts. In September, Morgan disappeared. He was last seen being forced into a carriage by four men later identified as Masons. When a corpse washed up on the shore of Lake Ontario, Morgan’s wife and friends claimed at first that it was his.

The Morgan story convinced many people that Masonry was a dangerous influence in the republic. The publicity surrounding the trials transformed local outrage into a political movement that, though small, had significant power in New York and parts of New England. This movement addressed Americans’ widespread dissatisfaction about economic and political change by giving them a handy explanation: the republic was controlled by a secret society.

In 1827, local anti-Masonic committees began meeting across the state of New York, committing not to vote for any political candidate who belonged to the Freemasons. This boycott grew, and in 1828, a convention in the town of LeRoy produced an “Anti-Masonic Declaration of Independence,” the basis for an Anti-Masonic Party. In 1828, Anti-Masonic politicians ran for state offices in New York, winning 12 percent of the vote for governor.

In 1830, the Anti-Masons held a national convention in Philadelphia. But after a dismal showing in the 1832 presidential elections, the leaders of the Anti-Masonic Party folded their movement into the new Whig Party. The Anti-Masonic Party’s absorption into the Whig coalition demonstrated the importance of conspiracy theories in American politics. Just as some of Andrew Jackson’s followers detected a vast foreign plot in the form of the Bank of the United States, some of his enemies could detect it in the form of the Freemasons. Others, called nativists, blamed immigrants.

Nativism

Nativists detected many foreign threats, but Catholicism may have been the most important. Nativists watched with horror as more and more Catholic immigrants (especially from Ireland and Germany) arrived in American cities. The immigrants professed different beliefs, often spoke unfamiliar languages, and participated in alien cultural traditions. Just as importantly, nativists remembered Europe’s history of warfare between Catholics and Protestants. They feared that Catholics would bring religious violence with them to the United States. Tapping into anxieties over the alleged encroachment of Catholicism and the troubling foreignness of transatlantic immigrants, the American Party, better known as the Know-Nothings, comprised an important faction in the early formation of the Whig party.

In the summer of 1834, a mob of Protestants attacked a Catholic convent near Boston. The rioters had read newspaper rumors that a woman was being held against her will by the nuns. Angry men broke into the convent and burned it to the ground. Later, a young woman named Rebecca Reed, who had spent time in the convent, published a memoir describing abuses she claimed the nuns had directed toward novices and students. The convent attack was among many eruptions of nativism, especially in New England and other parts of the Northeast, during the early nineteenth century.

Many Protestants saw the Catholic faith as a superstition that deprived individuals of the right to think for themselves and enslaved them to a dictator, the pope, in Rome. They accused Catholic priests of controlling their parishioners and preying sexually on young women. They feared that Catholicism would overrun and conquer the American political system, just as their ancestors had feared it would conquer England.

The painter and inventor Samuel F. B. Morse, for example, warned in 1834 that European tyrants were conspiring together to “carry Popery through all our borders” by sending Catholic immigrants to the United States. If they succeeded, he predicted, Catholic dominance in America would mean “the certain destruction of our free institutions.” Around the same time, the Protestant minister Lyman Beecher lectured in various cities, delivering a similar warning. “If the potentates of Europe have no design upon our liberties,” Beecher demanded, then why were they sending over “such floods of pauper emigrants—the contents of the poorhouse and the sweepings of the streets—multiplying tumults and violence, filling our prisons, and crowding our poorhouses, and quadrupling our taxation”—not to mention voting in American elections?

The Whig Party

The Whig Party had grown partly out of the political coalition of John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. The National Republicans, a loose alliance concentrated in the Northeast, had become the core of a new anti-Jackson movement. But Jackson’s enemies were a varied group; they included proslavery southerners angry about Jackson’s behavior during the Nullification Crisis as well as antislavery Yankees.

After they failed to prevent Andrew Jackson’s reelection, this fragile coalition formally organized as a new party in 1834 “to rescue the Government and public liberty.” Henry Clay, who had run against Jackson for president and was now serving again as a senator from Kentucky, held private meetings to persuade anti-Jackson leaders from different backgrounds to unite. He also gave the new Whig Party its anti-monarchical name, which alluded to the 18th century Whigs who had opposed royal power in England.[1]

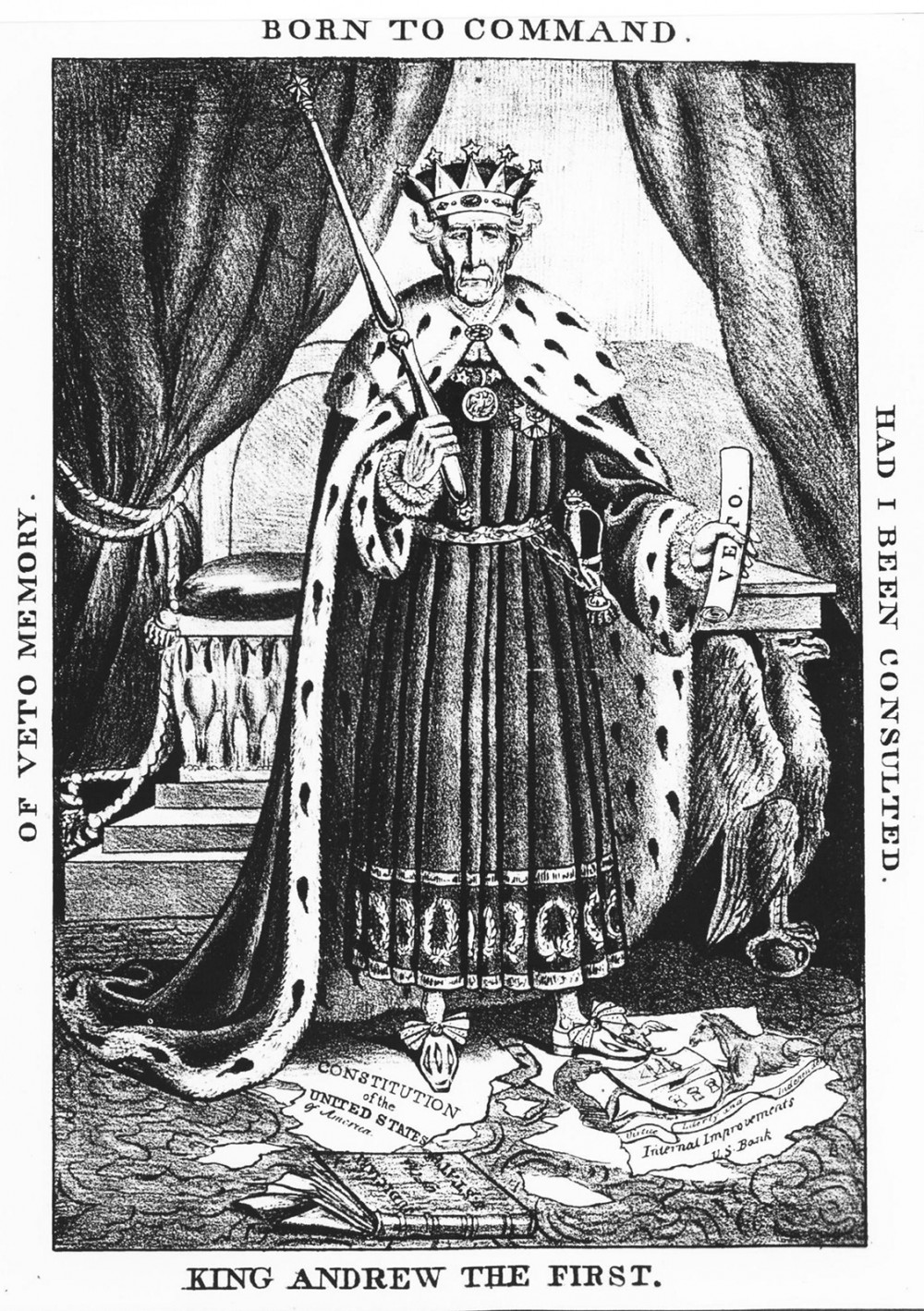

At first, the Whigs focused mainly on winning seats in Congress, opposing “King Andrew” from outside the presidency. They remained divided by regional and ideological differences. The Democratic presidential candidate, Vice President Martin Van Buren, easily won the election as Jackson’s successor in 1836. But the Whigs gained significant public support after the Panic of 1837, and they became increasingly well-organized. In late 1839, they held their first national convention in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Figure 1. Andrew Jackson portrayed himself as the defender of the common man, and in many ways he democratized American politics. His opponents, however, zeroed in on Jackson’s willingness to utilize the powers of the executive office. Unwilling to defer to Congress and absolutely willing to use his veto power, Jackson came to be regarded by his adversaries as a tyrant (or, in this case, “King Andrew I”.)

To Henry Clay’s disappointment, the convention voted to nominate not him but General William Henry Harrison of Ohio as the Whig candidate for president in 1840. Harrison was known primarily for defeating Shawnee warriors in the Northwest before and during the War of 1812, most famously at the Battle of Tippecanoe in present-day Indiana. Whig leaders viewed him as a candidate with broad patriotic appeal. They portrayed him as the “log cabin and hard cider” candidate, a plain man of the country, unlike the easterner Martin Van Buren. To balance the ticket with a southerner, the Whigs nominated Virginia senator and enslaver John Tyler as vice president. Tyler had been a Jackson supporter but had broken with him over states’ rights during the Nullification Crisis.

The presidential election contest of 1840 marked the culmination of the democratic revolution that swept the United States. By this time, the Second Party System had taken hold, a system whereby the older Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties had been replaced by the new Democratic and Whig Parties. Both Whigs and Democrats jockeyed for election victories and commanded the steady loyalty of political partisans. Large-scale presidential campaign rallies and emotional propaganda became the order of the day. Voter turnout increased dramatically under the second party system. Roughly 25 percent of eligible voters had cast ballots in 1828. In 1840, voter participation surged to nearly 80 percent.

The differences between the parties were largely about economic policies. Whigs advocated accelerated economic growth, often endorsing federal government projects to achieve that goal. Democrats did not view the federal government as an engine promoting economic growth and advocated a smaller role for the national government. The membership of the parties also differed: Whigs tended to be wealthier; they were prominent planters in the South and wealthy urban northerners—in other words, the beneficiaries of the market revolution. Democrats presented themselves as defenders of the common people against the elite.

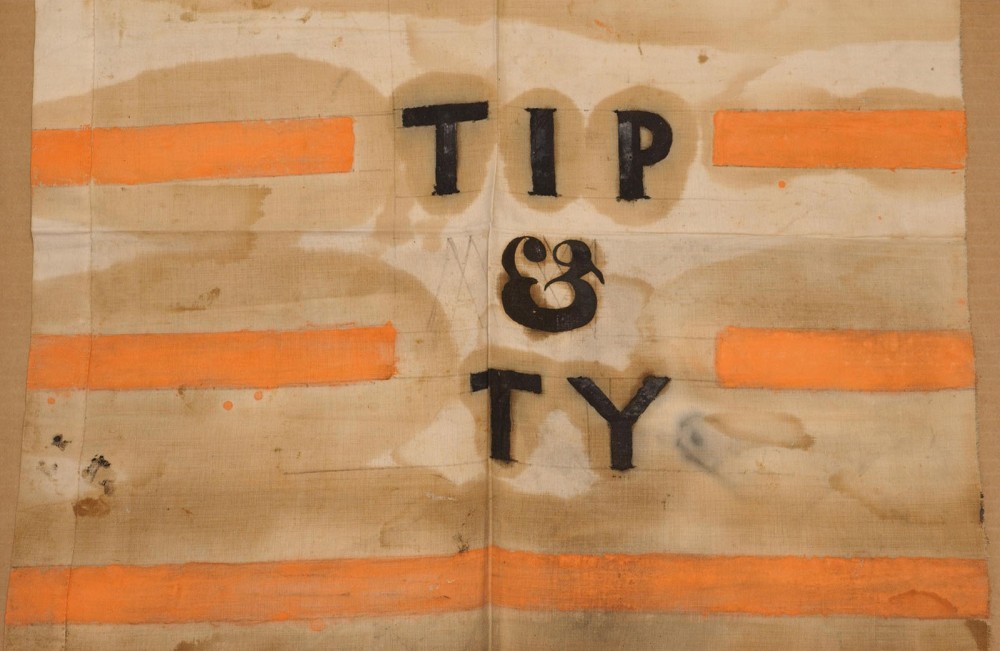

The campaign thrust Harrison into the national spotlight. Democrats tried to discredit him by declaring, “Give him a barrel of hard [alcoholic] cider and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him, and take my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin.” The Whigs turned the slur to their advantage by presenting Harrison as a man of the people who had been born in a log cabin (in fact, he came from a privileged background in Virginia), and the contest became known as the log cabin campaign. At Whig political rallies, the faithful were treated to whiskey made by the E. C. Booz Company, leading to the introduction of the word “booze” into the American lexicon. Tippecanoe Clubs, where booze flowed freely, helped in the marketing of the Whig candidate.

Figure 2. The Whig campaign song “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!” (a) and the anti-Whig flyers (b) that were circulated in response to the “log cabin campaign” illustrate the partisan fervor of the 1840 election.

The Whigs’ efforts, combined with their strategy of blaming Democrats for the lingering economic collapse that began with the hard-currency Panic of 1837, succeeded in carrying the day. A mass campaign with political rallies and party mobilization had molded a candidate to fit an ideal palatable to a majority of American voters, and in 1840 Harrison won what many consider the first modern election.

Figure 3. “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” was a popular and influential campaign song and slogan, helping the Whigs and William Henry Harrison (with John Tyler) win the presidential election in 1840. Pictured here is a campaign banner with shortened “Tip and Ty,” one of the many ways that Whigs made the “log cabin campaign” successful.

Try It

“His Accidency”

Although “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too” easily won the presidential election of 1840, this choice of ticket turned out to be disastrous for the Whigs. Harrison became ill (for unclear reasons, though tradition claims he contracted pneumonia after delivering a nearly two-hour inaugural address without an overcoat or hat) and died after just thirty-one days in office. Harrison thus holds the ironic honor of having the longest inaugural address and the shortest term in office of any American president. Vice President Tyler became president and soon adopted policies that looked far more like Andrew Jackson’s than like a Whig’s. After Tyler twice vetoed charters for another Bank of the United States, nearly his entire cabinet resigned, and the Whigs in Congress expelled “His Accidency” from the party.

The crisis of Tyler’s administration was just one sign of the Whig Party’s difficulty uniting around issues besides opposition to Democrats. The Whig Party would succeed in electing two more presidents, but it would remain deeply divided. Its problems would grow as the issue of slavery strained the Union in the 1850s. Unable to agree upon a consistent national position on slavery, and unable to find another national issue to rally around, the Whigs would break apart by 1856.

Try It

Glossary

log cabin campaign: the 1840 election, in which the Whigs presented William Henry Harrison as a man of the people

second party system: the system in which the Democratic and Whig Parties became the two main political parties after the decline of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties

Candela Citations

- The Tyranny and Triumph of the Majority. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/10-5-the-tyranny-and-triumph-of-the-majority. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Anti-Masons, Anti-Immigrants, and the Whig Coalition. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/09-democracy-in-america/#XI_Race_and_Jacksonian_Democracy. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- King Andrew the First. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:King_Andrew_the_First_(political_cartoon_of_President_Andrew_Jackson).jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tip and Ty banner. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tip_and_Ty_banner.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty: An American History (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 372. ↵