Learning Objectives

- Explain the evolution of American interest in overseas commercial and religious activity at the end of the nineteenth century

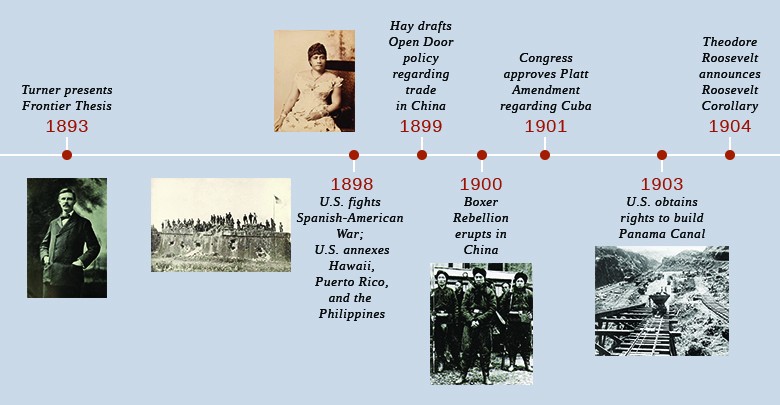

Figure 1. Major events related to U.S. foreign policy at the turn of the century.

During the time of Reconstruction, the U.S. government showed no significant interest in foreign affairs. Western expansion and the goal of Manifest Destiny still held the country’s attention, and American missionaries proselytized as far abroad as China, India, the Korean Peninsula, and Africa, but reconstruction efforts took up most of the nation’s resources. As the century came to a close, however, a variety of factors, from the closing of the American frontier to the country’s increased industrial production, led the United States to look beyond its borders. Countries in Europe were building their empires through global power and trade, and the United States did not want to be left behind.

America’s Limited but Aggressive Push Outward

On the eve of the Civil War, the country lacked the means to establish a strong position in international diplomacy. As of 1865, the U.S. State Department had barely sixty employees and no ambassadors representing American interests abroad. Instead, only two dozen American foreign ministers were located in key countries, and those often gained their positions not through diplomatic skills or expertise in foreign affairs but through bribes. Further limiting American potential for foreign impact was the fact that a strong international presence required a strong military—specifically a navy—which the United States, after the Civil War, had no interest in maintaining. Additionally, as late as 1890, with the U.S. Navy significantly reduced in size, a majority of vessels were classified as “Old Navy,” meaning a mixture of iron-hulled and wholly wooden ships. While the navy had introduced the first all-steel, triple-hulled steam engine vessels seven years earlier, they had only thirteen of them in operation by 1890.

Despite such widespread isolationist impulses and the sheer inability to maintain a strong international position, the United States moved ahead sporadically with a modest foreign policy agenda. The United States acquired its first Pacific territories with the Guano Islands Act of 1856. Guano—collected bird excrement—was a popular fertilizer integral to industrial farming. The act authorized and encouraged Americans to venture into the seas and claim islands with guano deposits for the United States.

Secretary of State William Seward, who held that position from 1861 through 1869, sought to extend American political and commercial influence in both Asia and Latin America. He pursued these goals through a variety of actions. A treaty with Nicaragua set the early course for the future construction of a canal across Central America. He also pushed through the annexation of the Midway Islands in the Pacific Ocean, which subsequently opened a more stable route to Asian markets. During frequent conversations with President Lincoln, among others, Seward openly spoke of his desire to obtain British Columbia, the Hawaiian Islands, portions of the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and other territories. He explained his motives to a Boston audience in 1867, when he professed his intention to give the United States “control of the world.”

Alaska

Figure 2. Although mocked in the press at the time as “Seward’s Folly,” Secretary of State William Seward’s acquisition of Alaska from Russia was a strategic boon to the United States.

Most notably, in 1867, Seward obtained the Alaskan Territory from Russia for a purchase price of $7.2 million. Fearing future loss of the territory through military conflict, as well as desiring to create challenges for Great Britain (which they had fought in the Crimean War), Russia had happily accepted the American offer. In the United States, several newspaper editors openly questioned the purchase and labeled it Seward’s Folly. They highlighted the lack of Americans who were likely to populate the vast region and lamented the prospective challenges of governing the native peoples in that territory. Only if gold were to be found, the editors claimed, would the secretive purchase be justified. That is exactly what happened. Seward’s purchase added an enormous territory to the country—nearly 600,000 square miles—and also gave the United States access to the rich mineral resources of the region, including the gold that trigged the Klondike Gold Rush at the close of the century. As was the case elsewhere in the American borderlands, Alaska’s industrial development wreaked havoc, particularly on the region’s Indigenous and Russian cultures.

Seward’s successor as Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, held the position from 1869 through 1877. Fish spent much of his time settling international disputes involving American interests, including claims that British assistance to the Confederates prolonged the Civil War for about two years. In these so-called Alabama claims, a U.S. senator charged that the Confederacy won a number of crucial battles with the help of one British cruiser and demanded $2 billion in British reparations. Alternatively, the United States would settle for the rights to Canada. A joint commission representing both countries eventually settled on a British payment of $15 million to the United States. In the negotiations, Fish also suggested adding the Dominican Republic as a territorial possession with a path towards statehood, as well as discussing the construction of a transoceanic canal with Colombia. Although neither negotiation ended in the desired result, they both expressed Fish’s intent to cautiously build an American empire without creating any unnecessary military antagonisms in the wake of the Civil War.

Business, Religions, and Social Interests Set the Stage for Empire

While the United States slowly pushed outward and sought to absorb the borderlands (and the Indigenous cultures that lived there), the country was also changing how it functioned. As a new industrial United States began to emerge in the 1870s, economic interests began to lead the country toward a more expansionist foreign policy. By forging new and stronger ties overseas, the United States would gain access to international markets for export, as well as better deals on the raw materials needed domestically. The concerns raised by the economic depression of the early 1890s further convinced business owners that they needed to tap into new markets, even at the risk of foreign entanglements.

As a result of these growing economic pressures, American exports to other nations skyrocketed in the years following the Civil War, from $234 million in 1865 to $605 million in 1875. By 1898, on the eve of the Spanish-American War, American exports had reached a height of $1.3 billion annually. Imports over the same period also increased substantially, from $238 million in 1865 to $616 million in 1898. Such an increased investment in overseas markets, in turn, strengthened Americans’ interest in foreign affairs.

Missionary Work

Businesses were not the only ones seeking to expand. Religious leaders and Progressive reformers joined businesses in their growing interest in American expansion, as both sought to increase the democratic and Christian influences of the United States abroad. Imperialism and Progressivism were compatible in the minds of many reformers who thought the Progressive impulses for democracy at home translated overseas as well. Editors of such magazines as Century, Outlook, and Harper’s supported an imperialistic stance as the democratic responsibility of the United States.

The first American missionaries arrived in Hawaii in 1820 and China in 1830. Missionaries often worked alongside business interests, and American missionaries in Hawaii, for instance, obtained large tracts of land and started lucrative sugar plantations. During the nineteenth century, Hawaii was ruled by an oligarchy based on the sugar companies, together known as the “Big Five.” Influenced by such works as Reverend Josiah Strong’s Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis (1885), missionaries sought to spread the gospel throughout the country and abroad. Led by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, among several other organizations, missionaries conflated Christian ethics with American virtues, and began to spread both gospels with zeal. This was particularly true among women missionaries, who composed over 60 percent of the overall missionary force. By 1870, missionaries abroad spent as much time advocating for the American version of a modern civilization as they did teaching the Bible.

The majority of American involvement in the Middle East prior to World War I came not in the form of trade but in education, science, and humanitarian aid. American missionaries led the way. Soon the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and the boards of missions of the Reformed Church of America became dominant in missionary enterprises. Missions were established in almost every country of the Middle East, and even though their efforts resulted in relatively few converts, missionaries helped establish hospitals and schools, and their work laid the foundation for the establishment of Western-style universities, such as Robert College in Istanbul, Turkey (1863), the American University of Beirut (1866), and the American University of Cairo (1919).

Lottie Moon, Missionary

Lottie Moon was a Southern Baptist missionary who spent more than forty years living and working in China. She began in 1873 when she joined her sister in China as a missionary, teaching in a school for Chinese women. Her true passion, however, was to evangelize and minister, and she undertook a campaign to urge the Southern Baptist missionaries to allow women to work beyond the classroom. Her letter campaign back to the head of the Mission Board provided a vivid picture of life in China and exhorted the Southern Baptist women to give more generously of their money and time. Her letters appeared frequently in religious publications, and it was her suggestion—that the week before Christmas be established as a time to donate to foreign missions—that led to the annual Christmas giving tradition. Lottie’s rhetoric caught on, and still today, the annual Christmas offering is made in her name.

We had the best possible voyage over the water—good weather, no headwinds, scarcely any rolling or pitching—in short, all that reasonable people could ask. . . . I spent a week here last fall and of course feel very natural to be here again. I do so love the East and eastern life! Japan fascinated my heart and fancy four years ago, but now I honestly believe I love China the best, and actually, which is stranger still, like the Chinese best.

—Charlotte “Lottie” Moon, 1877

Lottie remained in China through famines, the Boxer Rebellion (an uprising between 1899 and 1901 in when people resisted foreign imperialism and cultural influences, like Christianity), and other hardships. She fought against foot binding, a cultural tradition where girls’ feet were tightly bound to keep them from growing, and shared her personal food and money when those around her were suffering. But her primary goal was to evangelize her Christian beliefs to the people in China. She won the right to minister and personally converted hundreds of Chinese to Christianity. Lottie’s combination of moral certainty and selfless service was emblematic of the missionary zeal of the early American empire.

The Early Progressive Era

Social reformers of the early Progressive Era also performed work abroad that mirrored the missionaries. Many were influenced by recent scholarship on race-based intelligence and embraced the implications of social Darwinist theory that alleged inferior races were destined to poverty on account of their lower evolutionary status. While not all reformers espoused a racist view of intelligence and civilization, many of these reformers believed that the Anglo-Saxon race was mentally superior to others and owed the presumably less-evolved populations their stewardship and social uplift—a service the British writer Rudyard Kipling termed the white man’s burden.

By trying to help people in less industrialized countries achieve a higher standard of living and a better understanding of the principles of democracy, reformers hoped to contribute to a noble cause, but their approach suffered from the same paternalism that hampered Progressive reforms at home. Whether reformers and missionaries worked with native communities in the borderlands such as New Mexico; in the inner cities, like the Salvation Army; or overseas, their approaches had much in common. Their good intentions and willingness to work in difficult conditions shone through in the letters and articles they wrote from the field. Often in their writing, it was clear that they felt divinely empowered to change the lives of other, less fortunate, and presumably, less enlightened, people. Whether overseas or in the urban slums, they benefitted from the same passions but expressed the same paternalism.

Try It

Glossary

oligarchy: an arrangement in which a small group of insiders control a country, institution, or organization

Seward’s Folly: the pejorative name given by the press to Secretary of State Seward’s acquisition of Alaska in 1867

white man’s burden: associated with author Rudyard Kipling, this is the presumption that the White race was superior to allegedly less-developed peoples and bore a responsibility for their improvement

Candela Citations

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- U.S. History. Provided by: American YAWP. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/19-american-empire/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike. License Terms: Access for free at http://www.americanyawp.com/text/19-american-empire/