Learning Objectives

- Explain why the ideas of Social Darwinism were appealing to some during the Gilded Age

- Explain how American writers helped Americans to better understand the changes they faced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

Understanding Social Progress

In the late nineteenth century, Americans were living in a world characterized by rapid change. Western expansion, dramatic new technologies, and the rise of big business drastically influenced society in a matter of a few decades. For those living in fast-growing urban areas, the pace of change was even faster and harder to ignore. One result of this time of transformation was the emergence of a series of notable authors, who, whether writing fiction or nonfiction, offered a lens through which to better understand the shifts in American society.

Darwinism

One key idea of the nineteenth century that moved from the realm of science to the murkier ground of social and economic success was Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Darwin was a British naturalist who, in his 1859 work On the Origin of Species, made the case that species develop and evolve through natural selection, not through divine intervention. By “natural selection,” Darwin meant that specimens that are best adapted to their environment have the best chance to thrive and reproduce. Although biologists, botanists, and most of the scientific establishment widely accepted the theory of evolution at the time of Darwin’s publication, which they felt synthesized much of the previous work in the field, the theory remained controversial in the public realm for decades. In the 1870s, Darwin’s theories gained widespread traction among biologists, naturalists, and other scientists in the United States and, in turn, challenged the social, political, and religious beliefs of many Americans.

Social Darwinism

As vast and unprecedented new fortunes accumulated among a small number of wealthy Americans, new ideas arose to bestow moral legitimacy upon them. The British sociologist and biologist Herbert Spencer took Darwin’s ideas and applied them to Victorian-era society rather than the natural world and popularized the phrase survival of the fittest. The fittest, Spencer said, would demonstrate their superiority through economic success, while state welfare and private charity would lead to social degeneration—it would encourage the survival of the weak.[1]

William Graham Sumner, a sociologist at Yale, became the most vocal proponent of Social Darwinism. Sumner said, “Before the tribunal of nature a man has no more right to life than a rattlesnake; he has no more right to liberty than any wild beast; his right to pursuit of happiness is nothing but a license to maintain the struggle for existence.”[2] Not surprisingly, this ideology, which Darwin himself would have rejected as a gross misreading of his scientific discoveries, drew great praise from those who made their wealth at this time. However, critics of this theory were quick to point out that those who did not succeed often did not have the same opportunities or equal playing field that the ideology of social Darwinism purported.

Because social Darwinism could be used to justify extraordinary wealth and dismiss any obligation to the less fortunate, the ideas of social Darwinism spread quickly among wealthy Americans and their defenders. Social Darwinism identified an order that extended from the laws of nature to the workings of industrial society. All species and all societies, including modern humans, the theory went, were governed by a relentless competitive struggle for survival. The inequality of outcomes was to be not merely tolerated but encouraged and celebrated. It signified the progress of species and societies. Herbert Spencer’s major work, Synthetic Philosophy, sold nearly four hundred thousand copies in the United States by the time of his death in 1903. Gilded Age industrial elites, such as steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, inventor Thomas Edison, and Standard Oil’s John D. Rockefeller, were among Spencer’s prominent followers.

The theory of Social Darwinism remained a popular one among intellectual and business elites until it fell into disrepute in the 1930s and 1940s, as eugenicists began to utilize it in conjunction with their racial theories of genetic superiority.

Try It

Realism

Other thinkers of the day took Charles Darwin’s ideas in a more nuanced direction, focusing on different theories of realism that sought to understand the truth underlying the changes in the United States. These thinkers believed that ideas and social constructs must be proven to work before they could be accepted.

Philosopher William James was one of the key proponents of the closely related concept of pragmatism, which held that Americans needed to experiment with different ideas and perspectives to find the truth about American society, rather than assuming that there was truth in old, previously accepted models. Only by tying ideas, thoughts, and statements to actual objects and occurrences could one begin to identify a coherent truth, according to James. His work strongly influenced the subsequent avant-garde and modernist movements in literature and art, especially in understanding the role of the observer, artist, or writer in shaping the society they attempted to observe.

John Dewey built on the idea of pragmatism to create a theory of instrumentalism, which advocated the use of education in the search for truth. Dewey believed that education, specifically observation and change through the scientific method, was the best tool by which to reform and improve American society as it continued to grow ever more complex. This was a radical change from the usual model of education that stressed rote memorization, explicitly Christian values, and a grounding in Greek and Latin. Dewey strongly encouraged educational reforms designed to create an informed American citizenry that could then form the basis for other, much-needed progressive reforms in society.

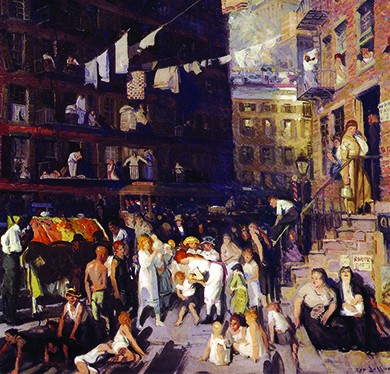

Figure 1. Like most examples of works by Ashcan artists, The Cliff Dwellers, by George Wesley Bellows, depicts the crowd of urban life realistically. (credit: Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Artists

In addition to the new medium of photography, popularized by Riis, novelists and other artists also embraced realism in their work. They sought to portray vignettes from real life in their stories. Visual artists such as George Bellows, Edward Hopper, and Robert Henri, among others, formed the Ashcan School of Art, which was interested primarily in depicting the urban lifestyle that was quickly gripping the United States at the turn of the century. Their works typically focused on working-class city life, including the slums and tenement houses, as well as working-class forms of leisure and entertainment. While some thinkers lamented the rise of teeming cities, these artists found beauty worth immortalizing within these new urban landscapes. Some novelists and journalists also popularized realism in literary works. Authors such as Stephen Crane, who wrote stark stories about life in the slums or during the Civil War, and Rebecca Harding Davis, who in 1861 published Life in the Iron Mills, embodied this popular style.

Mark Twain and Jack London

Mark Twain also sought realism in his books, whether it was the reality of the pioneer spirit, seen in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, or the issue of corruption in The Gilded Age, co-authored with Charles Dudley Warner in 1873. Frequently, his works had humorous antagonists, whose fraud and grift lampooned the era’s desire to accumulate wealth. The narratives and visual arts of these realists could nonetheless be highly stylized, crafted, and even fabricated, since their goal was the effective portrayal of social realities they thought required reform.

Link to Learning

Mark Twain’s lampoon of author Horatio Alger demonstrates Twain’s commitment to realism by mocking the myth set out by Alger, whose stories followed a common theme in which a poor but honest boy goes from rags to riches through a combination of “luck and pluck.” See how Twain twists Alger’s hugely popular storyline in this piece of satire.

Some authors, such as Jack London, who wrote Call of the Wild, embraced a school of thought called naturalism, which concluded that the laws of nature and the natural world were the only truly relevant laws governing humanity. In an age that was industrializing and mechanizing at a worrying pace, London argued for the primacy of the vast natural world.

Figure 2. Jack London poses with his dog Rollo in 1885 (a). The cover of Jack London’s Call of the Wild (b) shows the dogs in the brutal environment of the Klondike. The book tells the story of Buck, a dog living happily in California until he is sold to be a sled dog in Canada. There, he must survive harsh conditions and brutal behavior, but his innate animal nature takes over and he prevails. The story clarifies the struggle between humanity’s nature versus the nurturing forces of society.

Women also vocalized new discontents through literature. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” attacked the idea of women as inherently domestic. In her work, she critiqued Victorian psychological remedies administered to women that were premised on the assumption of domesticity, such as the “rest cure.”

Kate Chopin

Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, set in the American South, likewise criticized the domestic and familial role ascribed to women by society and gave expression to feelings of malaise (uneasiness), desperation, and desire. Such literature directly challenged the status quo of the Victorian era’s constructions of femininity and feminine virtue, as well as established feminine roles. Chopin, widely regarded as the foremost woman short story writer and novelist of her day, sought to portray a realistic view of women’s lives in late nineteenth-century America, thus paving the way for more explicit feminist literature in generations to come. Although Chopin never described herself as a feminist per se, her reflective works on her experiences as a southern woman introduced a form of creative nonfiction that captured the struggles of women in the United States through their own individual experiences. She also was among the first authors to openly address the race issue of miscegenation. In her work Desiree’s Baby, Chopin specifically explores the Creole community of her native Louisiana in depths that exposed the reality of racism in a manner seldom seen in the literature of her time.

Kate Chopin: An Awakening in an Unpopular Time

Author Kate Chopin grew up in the American South and later moved to St. Louis, where she began writing stories to make a living after the death of her husband. She published her works throughout the late 1890s, with stories appearing in literary magazines and local papers. It was her second novel, The Awakening, which gained her notoriety and criticism in her lifetime, and ongoing literary fame after her death.

Figure 3. Critics railed against Kate Chopin, the author of the 1899 novel The Awakening, criticizing its stark portrayal of a woman struggling with societal confines and her own desires. In the twentieth century, scholars rediscovered Chopin’s work and The Awakening is now considered part of the canon of American literature.

The Awakening, set in the New Orleans society that Chopin knew well, tells the story of a woman struggling with the constraints of marriage who ultimately seeks her own fulfillment over the needs of her family. The book deals far more openly than most novels of the day with questions of women’s sexual desires. It also flouted nineteenth-century conventions by looking at the protagonist’s struggles with the traditional role expected of women.

While a few contemporary reviewers saw merit in the book, most criticized it as immoral and unseemly. It was censored, called “pure poison,” and critics railed against Chopin herself. While Chopin wrote squarely in the tradition of realism that was popular at this time, her work covered ground that was considered “too real” for comfort. After the negative reception of the novel, Chopin retreated from public life and discontinued writing. She died five years after its publication. After her death, Chopin’s work was largely ignored, until scholars rediscovered it in the late twentieth century, and her books and stories came back into print. The Awakening in particular has been recognized as vital to the earliest edges of the modern feminist movement.

Excerpts from interviews with David Chopin, Kate Chopin’s grandson, and a scholar who studies her work provide interesting perspectives on the author and her views.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

African American poet, playwright, and novelist of the realist period, Paul Laurence Dunbar dealt with issues of race at a time when most reform-minded Americans preferred to focus on other issues. Through his combination of writing in both standard English and Black dialect, Dunbar delighted readers with his rich portrayals of the successes and struggles associated with Black life in America. As with Chopin and Harding, Dunbar’s writing highlighted parts of the American experience that were not well understood by the dominant demographic of the country. In their work, these authors provided readers with insights into a world that was not necessarily familiar to them and also gave hidden communities—be it iron mill workers, southern women, or Black men—a sense of voice.

Paul LAurence Dunbar

Dunbar conveys the Black struggle for equality and dignity in his poem Sympathy (1899). It was later used as a springboard for Maya Angelou’s masterpiece, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.”

I know what the caged bird feels, alas!

When the sun is bright on the upland slopes;

When the wind stirs soft through the springing grass,

And the river flows like a stream of glass;

When the first bird sings and the first bud opes,

And the faint perfume from its chalice steals –

I know what the caged bird feels!I know why the caged bird beats his wing

Till its blood is red on the cruel bars;

For he must fly back to his perch and cling

When he fain would be on the bough a-swing;

And a pain still throbs in the old, old scars

And they pulse again with a keener sting –

I know why he beats his wing!I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore, –

When he beats his bars and he would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings –

I know why the caged bird sings!

Critics of Modern America

While many Americans at this time, both everyday working people and theorists, felt the changes of the era would lead to improvements and opportunities, there were critics of the emerging social shifts as well. Although less popular than Twain and London, authors such as Edward Bellamy, Henry George, and Thorstein Veblen were also influential critics of the industrial age. While their critiques were quite distinct from each other, all three believed that the industrial age was a step in the wrong direction for the country.

Looking Backward

One of the most popular novels of the nineteenth century, Edward Bellamy’s 1888 Looking Backward, was a national sensation. In it, a man falls asleep in Boston in 1887 and awakens in 2000 to find society radically altered.

In the book, Bellamy predicts the future advent of credit cards, cable entertainment, and “super-store” cooperatives that resemble a modern-day Wal-Mart. Poverty, disease, and competition gave way as new industrial armies cooperated to build a utopia of social harmony and economic prosperity. Looking Backward proved to be a popular bestseller (third only to Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben Hur among late nineteenth-century publications) and appealed to those who felt the industrial age of big business was sending the country in the wrong direction.

Looking Backward: 2000–1887

Bellamy’s vision of a reformed society enthralled readers, inspired hundreds of Bellamy clubs, and pushed many young readers onto the road to reform. It led countless Americans to question the realities of American life in the nineteenth century:

“I am aware that you called yourselves free in the nineteenth century. The meaning of the word could not then, however, have been at all what it is at present, or you certainly would not have applied it to a society of which nearly every member was in a position of galling personal dependence upon others as to the very means of life, the poor upon the rich, or employed upon employer, women upon men, children upon parents.”[3]

Think about if you were to write a similar type story today—how do you envision society working differently 113 years in the future?

Eugene Debs, who led the national Pullman Railroad Strike in 1894, later commented on how Bellamy’s work in Looking Backward influenced him to adopt socialism as the answer to the exploitative industrial capitalist model. In addition, Bellamy’s work spurred the publication of no fewer than thirty-six additional books or articles by other writers, either supporting Bellamy’s outlook or directly criticizing it. In 1897, Bellamy felt compelled to publish a sequel, entitled Equality, in which he further explained ideas he had previously introduced concerning educational reform and women’s equality, as well as a world of vegetarians who speak a universal language.

Progress and Poverty

Another author whose work illustrated the criticisms of the day was nonfiction writer Henry George, an economist best known for his 1879 work Progress and Poverty, which criticized the inequality created by an industrial economy. He suggested that, while people should own that which they create, all land and natural resources should belong to all equally, and should be taxed through a “single land tax” in order to disincentivize private land ownership. His thoughts influenced many economic progressive reformers, as well as led directly to the creation of the now-popular board game, Monopoly.

Another critique of late nineteenth-century American capitalism was Thorstein Veblen, who lamented in The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) that capitalism created a middle class more preoccupied with its own comfort and consumption than with maximizing production. In coining the phrase “conspicuous consumption,” Veblen identified the means by which one class of nonproducers exploited the working class that produced the goods for their consumption. Such practices, including the creation of business trusts, served only to create a greater divide between the haves and have-nots in American society and resulted in economic inefficiencies that required correction or reform.

Try It

Review Question

Glossary

instrumentalist: a theory promoted by John Dewey, who believed that education was key to the search for the truth about ideals and institutions

naturalism: a theory of realism that states that the laws of nature and the natural world were the only relevant laws governing humanity

pragmatism: a doctrine supported by philosopher William James, which held that Americans needed to experiment and find the truth behind underlying institutions, religions, and ideas in American life, rather than accepting them on faith

realism: a collection of theories and ideas that sought to understand the underlying changes in the United States during the late nineteenth century

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Mark Lempke for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Sympathy. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sympathy_(poem). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike