Learning Objectives

- Describe the role of the Open Door in U.S. foreign policy with China

- Explain how U.S. diplomatic relations with Japan differed from the rest of East Asia

While American forays into empire building began with military action, the country grew its scope and influence through other methods as well. In particular, the United States used its economic and industrial capacity to add to its empire, as can be seen in a study of the China market and the “Open Door Notes” discussed below.

Why China?

The United States had long been involved in Pacific commerce; American ships had been traveling to China since 1784. As a percentage of total American foreign trade, Asian trade remained comparatively small, and yet the idea that Asian markets were vital to American commerce affected American policy and, when those markets were threatened, prompted interventions. With the defeat of the Spanish navy in the Atlantic and Pacific, and specifically with the addition of the Philippines as a base for American ports and coaling stations, the United States was ready to try and assert a dominant position relative to China.

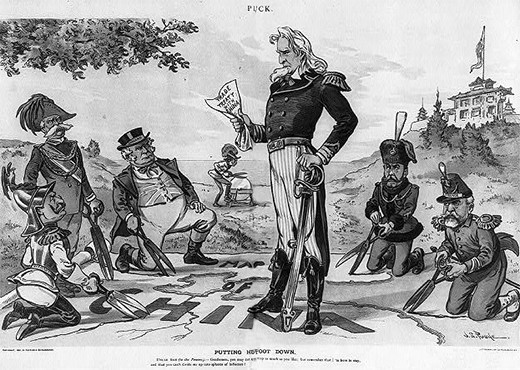

Figure 1. This political cartoon shows Uncle Sam standing on a map of China, while Europe’s imperialist nations (from left to right: Germany, Spain, Great Britain, Russia, and France) try to cut out their “sphere of influence.”

American businesses were not alone in seeing opportunities in the region. Other countries—including Japan, Russia, Great Britain, France, and Germany—also hoped to make inroads in China. Previous treaties between Great Britain and China in 1842 and 1844 during the Opium Wars, when the British Empire militarily coerced the Chinese empire to accept the import of Indian opium in exchange for its tea, had forced an “open door” policy on China, in which all foreign nations had free and equal access to Chinese ports. This was at a time when Great Britain maintained the strongest economic relationship with China; however, other western nations used the new arrangement to send Christian missionaries, who began to work across inland China.

By 1897, Germany had obtained exclusive mining rights in northern coastal China as reparations for the murder of two German missionaries. In 1898, Russia obtained permission to build a railroad across northeastern Manchuria. One by one, each country carved out their own sphere of influence, where they could control markets through tariffs and transportation, and thus ensure their share of the Chinese market.

Alarmed by the pace at which foreign powers further divided China into pseudo-territories, and worried that they had no significant piece for themselves, the United States government intervened. In contrast to European nations, however, American businesses wanted the whole market, not just a share of it. They wanted to do business in China with no artificially constructed spheres or boundaries to limit the extent of their trade, but without the territorial entanglements or legislative responsibilities that anti-imperialists opposed. With the approval and assistance of Secretary of State John Hay, several American businessmen created the American Asiatic Association in 1896 to pursue greater trade opportunities in China.

The Open Door Notes

In 1899, Secretary of State Hay made a bold move to acquire China’s vast markets for American access by introducing Open Door Notes, a series of circular notes that Hay himself drafted as an expression of U.S. interests in the region and sent to the other competing powers. These notes, if agreed to by the other five nations maintaining spheres of influences in China, would erase all spheres and essentially open all doors to free trade, with no special tariffs or transportation controls that would give unfair advantages to one country over another. Specifically, the notes required that all countries agree to maintain free access to all treaty ports in China, to pay railroad charges and harbor fees (with no special access) and that only China would be permitted to collect any taxes on trade within its borders. While on paper, the Open Door Notes would offer equal access to all, the reality was that it greatly favored the United States. Free trade in China would give American businesses the ultimate advantage, as American companies were producing higher-quality goods than other countries, and were doing so more efficiently and less expensively. The “open doors” would flood the Chinese market with American goods, virtually squeezing other countries out of the market.

Watch It

This video explains America’s economic interests in China and the reasoning for John Hay’s Open Door Notes.

Browse the U.S. State Department’s Milestones: 1899—1913 to learn more about Secretary of State John Hay and the strategy and thinking behind the Open Door Notes.

You can view the transcript for “John Hay’s Open Door Policy for China” here (opens in new window).

Figure 2. The Boxer Rebellion in China sought to expel all western influences, including Christian missionaries and trade partners.

Although the foreign ministers of the other five nations sent half-hearted replies on behalf of their respective governments, with some outright denying the viability of the notes, Hay proclaimed them the new official policy on China, and American goods flooded the nation. China welcomed the notes, as they also stressed the U.S. commitment to preserving the Chinese government and territorial integrity.

The Boxer Rebellion

The notes were invoked barely a year later, when a group of Chinese insurgents, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists—also known as the Boxer Rebellion—fought to expel all western nations and their influences from China. The United States, along with Great Britain and Germany, sent over two thousand troops to end the rebellion. The troops signified America’s commitment to maintaining its commercial dominance in China.

In the aftermath of the rebellion, China was left with an enormous penalty to pay back, and the United States refused to allow other countries to expand their control over China. Despite subsequent efforts, by Japan in particular, to undermine Chinese authority in 1915 and again during the Manchurian crisis of 1931, the United States remained resolute in defense of the open door principles through World War II. Only when China turned to communism in 1949 following an intense civil war did the principle become relatively meaningless. However, for nearly half a century, U.S. military involvement and a continued relationship with the Chinese government cemented their roles as preferred trading partners, illustrating how America used economic power, as well as military might, to grow its empire.

watch It

This video explains more about the Boxer Rebellion in China.

Try It

Intervention in Russia and Japan

Although he supported the Open Door Notes as an advantageous economic policy in China, Roosevelt lamented the fact that the United States had no strong military presence in the region to enforce it. Clearly, without a military presence, he could not effectively use his “big stick” threat to achieve his foreign policy goals. As a result, when conflicts did arise on the other side of the Pacific, Roosevelt adopted a policy of maintaining a balance of power among the nations in the region. This was particularly evident when the Russo-Japanese War erupted in 1904.

Link to Learning

Watch this video to learn more about the context of the Russo-Japanese war.

Figure 3. Japan’s defense against Russia was supported by President Roosevelt, but when Japan’s ongoing victories put the United States’ own Asian interests at risk, he stepped in.

Initially, Roosevelt supported the Japanese position. However, when the Japanese fleet quickly achieved victory after victory, Roosevelt grew concerned over the growth of Japanese influence in the region and the continued threat that it represented to China and American access to those markets. Wishing to maintain the aforementioned balance of power, in 1905 Roosevelt arranged for diplomats from both nations to attend a secret peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The resultant negotiations secured peace in the region, with Japan gaining control over Korea, several former Russian bases in Manchuria, and the southern half of Sakhalin Island. These negotiations also garnered the Nobel Peace Prize for Roosevelt, the first American to receive the award.

When Japan later exercised its authority over its gains by forcing American business interests out of Manchuria in 1906–1907, Roosevelt felt he needed to invoke his “big stick” foreign policy, even though the distance was great. He did so by sending the U.S. Great White Fleet on maneuvers in the western Pacific Ocean as a show of force from December 1907 through February 1909. Publicly described as a goodwill tour, the message to the Japanese government regarding American interests was clear. Subsequent negotiations reinforced the Open Door policy throughout China and the rest of Asia.

Gentleman’s agreement

Roosevelt’s feelings about the Japanese were ambivalent at best. Because they were not White, Roosevelt was inclined to write them off as inferior to people of Anglo-Saxon heritage. However, their victory in the Russo-Japanese War complicated this, because Japan had defeated a European nation in conventional warfare. Roosevelt also approved of Japan’s takeover of Korea, seeing it as part of the natural political order where a stronger state dominates and watches over a weaker state. The rising power of Japan meant that Roosevelt felt both respect for their martial power and an awareness that he also had to cultivate a less-hostile relationship. This intersected with domestic politics and immigration.

In the United States, nativism was on the rise, and on the West Coast, racism against Asian immigrants was growing. In San Francisco, schools had already been racially segregated on paper, but up until 1905 these policies had not been acted upon. When the city of San Francisco began enforcing racial segregation against Japanese school children, it led to protests from the Japanese government. Roosevelt, not wanting to anger Japan, negotiated a so-called gentleman’s agreement. In exchange for the Japanese government quietly reducing immigration to the United States (Roosevelt agreed to block any public, legal immigration bans in order to avoid embarrassing Tokyo), school segregation would end. While racism on the West Coast persisted towards Japanese-Americans, Japan’s military and political strength guaranteed that people of Japanese descent benefited from a degree of protection that Chinese-Americans and Korean-Americans did not possess.

Try It

Review Question

Glossary

Boxer Rebellion: an insurgency in China led by a group known as the Righteous and Harmonious Fists that tried to end intrusive Western influence and power in China

Great White Fleet: a fleet of U.S. battleships that circled the globe and visited numerous countries, meant to showcase a modernized and improved navy

Open Door Notes: the circular notes sent by Secretary of State Hay claiming that there should be “open doors” in China, allowing all countries equal and total access to all markets, ports, and railroads without any special considerations from the Chinese authorities; while ostensibly leveling the playing field, this strategy greatly benefited the efficient industrial capacity of the United States

sphere of influence: the goal of foreign countries such as Japan, Russia, France, and Germany to carve out an area of the Chinese market that they could exploit through tariff and transportation agreements

Russo-Japanese War: the conflict that lasted from 1904 to 1905 between Russia and Japan, ending in a Japanese victory

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Zeb Larson for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- U.S. History. Provided by: American YAWP. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/19-american-empire/. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sound Smart: The Boxer Rebellion. Provided by: History. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AcwbMmUWHGw&feature=emb_logo. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- John Hay's Open Door Policy for China. Provided by: NBC News Learn. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wSH5-GxD-c8. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License