Learning Objectives

- Describe the economic and political circumstances in the U.S. on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash

- Detail the events of the stock market crash of 1929

Figure 1. Timeline of major events of the Depression-era. (credit “courthouse”: modification of work by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

The Early Days of Hoover’s Presidency

Upon his inauguration, President Hoover set forth an agenda that he hoped would continue the “Coolidge prosperity” of the previous administration. While accepting the Republican Party’s nomination in 1928, Hoover commented, “Given the chance to go forward with the policies of the last eight years, we shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation forever.” In the spirit of normalcy that defined the Republican ascendancy of the 1920s, Hoover planned to immediately overhaul federal regulations with the intention of allowing the nation’s economy to grow unfettered by any controls. The role of the government, he contended, should be to create a partnership with the American people, in which the latter would rise (or fall) on their own merits and abilities. He felt the less government intervention in their lives, the better.

Yet, to listen to Hoover’s later reflections on Franklin Roosevelt’s first term in office, one could easily mistake his vision for America for the one held by his successor. Speaking in 1936 before an audience in Denver, Colorado, he acknowledged that it was always his intent as president to ensure “a nation built of homeowners and farm owners. We want to see more and more of them insured against death and accident, unemployment and old age,” he declared. “We want them all secure.”[1] Such humanitarianism was not uncommon to Hoover. Throughout his early career in public service, he was committed to relief for people around the world. In 1900, he coordinated relief efforts for foreign nationals trapped in China during the Boxer Rebellion. At the outset of World War I, he led the food relief effort in Europe, specifically helping millions of Belgians who faced German forces. President Woodrow Wilson subsequently appointed him head of the U.S. Food Administration to coordinate rationing efforts in America as well as to secure essential food items for the Allied forces and citizens in Europe.

Hoover’s first months in office hinted at the reformist, humanitarian spirit that he had displayed throughout his career. He continued the civil service reform of the early twentieth century by expanding opportunities for employment throughout the federal government. In response to the Teapot Dome Affair, which had occurred during the Harding administration, he invalidated several private oil leases on public lands. He directed the Department of Justice, through its Bureau of Investigation, to crack down on organized crime, resulting in the arrest and imprisonment of Al Capone. By the summer of 1929, he had signed into law the creation of a Federal Farm Board to help farmers with government price supports, expanded tax cuts across all income classes, and set aside federal funds to clean up slums in major American cities.

To directly assist overlooked populations, he created the Veterans Administration and expanded veterans’ hospitals, established the Federal Bureau of Prisons to oversee incarceration conditions nationwide, and reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs to further protect Native Americans. Just prior to the stock market crash, he even proposed the creation of an old-age pension program, promising fifty dollars monthly to all Americans over the age of sixty-five—a proposal remarkably similar to the social security benefit that would become a hallmark of Roosevelt’s subsequent New Deal programs. As the summer of 1929 came to a close, Hoover remained a popular successor to Calvin “Silent Cal” Coolidge, and all signs pointed to a successful administration.

Try It

The Great Crash

The promise of the Hoover administration was cut short when the stock market lost almost one-half of its value in the fall of 1929, plunging many Americans into financial ruin. However, as a singular event, the stock market crash itself did not cause the Great Depression that followed. Only approximately 10 percent of American households held stock investments and speculated in the market, yet nearly a third would lose their life savings and jobs in the ensuing depression. The connection between the crash and the subsequent decade of hardship was complex, involving underlying weaknesses in the economy that many policymakers had long ignored.

Events Leading to the Crash

To understand the crash, it is useful to address the decade that preceded it. The prosperous 1920s ushered in a feeling of euphoria among middle-class and wealthy Americans, and people began to speculate on wilder investments. The government was a willing partner in this endeavor: The Federal Reserve followed a brief postwar recession in 1920–1921 with a policy of setting interest rates artificially low, as well as easing the reserve requirements on the nation’s largest banks. As a result, the money supply in the U.S. increased by nearly 60 percent, which convinced even more Americans of the safety of investing in questionable schemes. They felt that prosperity was boundless and that extreme risks were likely tickets to wealth. Speculation, where investors bought into high-risk schemes that they hoped would pay off quickly, became the norm. Several banks, including deposit institutions that originally avoided investment loans, began to offer easy credit, allowing cash-poor people to invest.

Selling Optimism and Risk

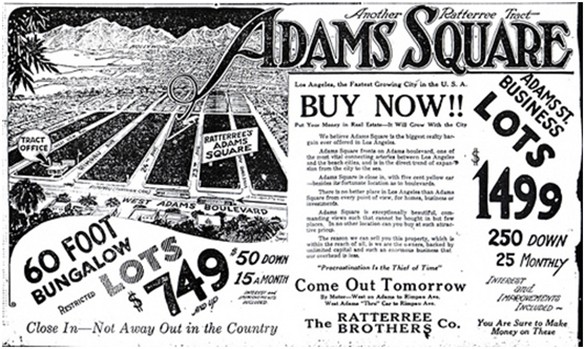

Figure 4. This real estate advertisement from Los Angeles illustrates the hard-sell techniques and easy credit offered to those who wished to buy in. Unfortunately, the opportunities being promoted with these techniques were of little value, and many lost their investments. (credit: “army.arch”/Flickr)

Advertising offers a useful window into the popular perceptions and beliefs of an era. By seeing how businesses were presenting their goods to consumers, it is possible to sense the hopes and aspirations of people at that moment in history. In the 1920s, advertisers were selling opportunity and euphoria, further feeding the notions of many Americans that prosperity would never end.

In the decade before the Great Depression, the optimism of the American public was seemingly boundless. Advertisements from that era show large new cars, timesaving labor devices, and, of course, land. This advertisement for California real estate illustrates how realtors in the West, much as they had in the Florida land boom, used a combination of the hard sell and easy credit. “Buy now!!” the ad shouts. “You are sure to make money on these.” In great numbers, people took the bait.

With easy access to credit and insistent, reassuring advertisements like this one, many felt that they could not afford to miss out on such an opportunity. Unfortunately, overspeculation in California and hurricanes along the Gulf Coast and in Florida conspired to burst this land bubble, and would-be millionaires were left with nothing but the ads that once pulled them in.

The Florida land boom went bust in 1925–1926. A combination of negative press about the speculative nature of the boom, IRS investigations into the questionable financial practices of several land brokers, and a railroad embargo that limited the delivery of construction supplies into the region, significantly hampered investor interest. The subsequent Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 drove most land developers into outright bankruptcy.

However, speculation continued throughout the decade, this time in the stock market. Buyers purchased stock “on margin”—buying for a small down payment with borrowed money, with the intention of quickly selling at a much higher price before the remaining payment came due—which worked well as long as prices continued to rise.

Buying stocks on margin brought hundreds of thousands of new investors into the market. Under the loose rules of the time, they could purchase a stock by simply laying down 10 percent of its cost and borrowing the rest from banks or stockbrokers—buying, for example, $1,000 worth of a stock and handing over just $100 in cash. If your $1,000 in stocks then rose in value to $1,075, you made $75 on your $100 investment when you sold the stock—or so it seemed. That $75 profit existed only on paper, because you still had to pay back the bank or broker who loaned you the $900 at a rate of 14 to 19 percent. Investors at that time did not seem to care all that much, however, because they were making money. To many, buying stocks on margin was easy money and a way to get rich quickly. But if your stock went down in value, the broker would demand more and more of the loan to be paid in cash to cover the loss.

Speculators were aided by retail stock brokerage firms, which catered to average investors anxious to enter the market but lacking direct ties to investment banking houses or larger brokerage firms. When prices began to fluctuate in the summer of 1929, investors sought excuses to continue their speculation. When fluctuations turned to clear, steady losses, everyone started to sell. As September began to unfold, the Dow Jones Industrial Average peaked at a value of 381 points, or roughly ten times the stock market’s value at the start of the 1920s.

Several warning signs portended the impending crash but went unheeded by Americans still giddy over the potential fortunes that speculation might promise. A brief downturn in the market on September 18, 1929, raised questions among more-seasoned investment bankers, leading some to predict an end to high stock values. However, these worries did little to stem the tide of investment. Even the collapse of the London Stock Exchange on September 20 failed to fully curtail the optimism of American investors.

Try It

Figure 5. Crowds of people gather outside the New York Stock Exchange following the crash of 1929. Library of Congress.

Market Fluctuations

The market high of September 3, 1929, came the day after the end of the long Labor Day weekend. It also marked the end of what later became known as the “summer of fun,” when a craze for dance marathons, flagpole-sitting contests, and other zany fads seemed to have taken hold of the country. There was a madness in the air that seemed hard to explain. Among other things, this was the moment when Americans started drinking sauerkraut juice for no apparent reason—a fact noted by Maury Klein in his definitive narrative on the history of the crash. He wrote: “In the summer of 1929 much of America was on an artificial high. It was a high not born of drugs but of an illusion that the prosperity and the good times then being enjoyed were made of new miracle ingredients that would last forever.”

Black Thursday

Following that peak, stock prices fell by approximately 10 percent during September but then rose again by about 8 percent by the middle of October. The fluctuations seemed relatively normal because the market often went up and down. However, on Thursday, October 24, a selling panic began and 13 million shares were traded, which far surpassed the average of four million shares per day the preceding month. The market had taken a nose dive, and investors found themselves scrambling as their paper fortunes began to dwindle or disappear. The technology of the time—telephone, telegraph, and the new paper ticker tape machines that displayed stock values—could not keep up with the pace of trading, and many investors did not learn of their losses until late that evening. October 24 was quickly given the name “Black Thursday.”

Black Tuesday

Figure 6. October 29, 1929, or Black Tuesday, witnessed thousands of people racing to Wall Street discount brokerages and markets to sell their stocks. Prices plummeted throughout the day, eventually leading to a complete stock market crash.

On October 29, later known as Black Tuesday, the stock market began its long precipitous fall. No one even heard the opening bell on Wall Street that day, as shouts of “Sell! Sell!” drowned it out. In the first three minutes alone, nearly three million shares of stock, accounting for $2 million of wealth, changed hands. The volume of Western Union telegrams tripled, and telephone lines could not meet the demand, as investors sought any means available to dump their stock immediately. Rumors spread of investors jumping from their office windows. Fistfights broke out on the trading floor, where one broker fainted from physical exhaustion. Stock trades happened at such a furious pace that runners had nowhere to store the trade slips, and so they resorted to stuffing them into trash cans. Although the stock exchange’s board of governors briefly considered closing the exchange early, they subsequently chose to let the market run its course, lest the American public panic even further at the thought of closure. When the final bell rang, errand boys spent hours sweeping up tons of paper, ticker tape, and sales slips.

Stock values evaporated. Shares of U.S. Steel dropped from $262 to $22. General Motors stock fell from $73 a share to $8. Four-fifths of J. D. Rockefeller’s fortune—the greatest in American history—vanished. Stockholders traded over sixteen million shares and lost over $14 billion in wealth in a single day. To put this in context, a trading day of three million shares was considered a busy day on the stock market. People unloaded their stock as quickly as they could, accepting dramatic losses. Banks, facing debt and seeking to protect their own assets, demanded payment for the loans they had provided to individual investors. Those individuals who could not afford to pay found their stocks sold immediately and their life savings wiped out in minutes, yet their debt to the bank still remained.

The financial outcome of the crash was devastating. Between September 1 and November 30, 1929, the stock market lost over one-half of its value, dropping from $64 billion to approximately $30 billion. Any effort to stem the tide was, as one historian noted, tantamount to bailing Niagara Falls with a bucket. The crash affected many more than the relatively few Americans who invested in the stock market. While only 10 percent of households had investments, over 90 percent of all banks held investments in the stock market. Many banks failed because of their inadequate cash reserves. This was in part due to the Federal Reserve lowering the limits of cash reserves that banks were traditionally required to hold in their vaults, as well as the fact that many banks invested in the stock market themselves. Eventually, thousands of banks closed their doors after losing all of their assets, leaving their customers penniless. While a few savvy investors got out at the right time and eventually made fortunes buying up discarded stock, those success stories were rare. Housewives who speculated with grocery money, bookkeepers who embezzled company funds hoping to strike it rich and pay the funds back before getting caught, and bankers who used customer deposits to follow speculative trends all lost. While the stock market crash was the trigger, the lack of appropriate economic and banking safeguards, along with a public psyche that pursued wealth and prosperity at all costs, allowed this event to spiral downward into a depression.

The National Humanities Center

The National Humanities Center has brought together a selection of newspaper commentary from the 1920s, from before the crash to its aftermath. Read through to see what journalists and financial analysts thought of the situation at the time. Consider the following questions as you read:

- What warnings were given prior to the Stock Market Crash?

- What reasons are given for why investors continued to borrow and speculate despite the warnings?

- How can you interpret the commentary from one day after the crash? What kind of messages are being sent to the readers?

Review Question

Glossary

Black Thursday: the New York Stock Exchange lost 11 percent of its value on October 24, 1929; this was the first warning sign for American investors.

Black Tuesday: October 29, 1929, when a mass panic caused a crash in the stock market and stockholders divested over sixteen million shares, causing the overall value of the stock market to drop precipitously

brokerage firms: businesses that facilitate transactions such as the buying and selling of stocks on behalf of their clients. In return, they charge a brokerage commission.

(buying) on margin: borrowing money from a broker in order to purchase stock. Think of it as a loan from your brokerage; margin trading allows you to buy more stock than you’d be able to normally.

speculation: the practice of investing in risky financial opportunities in the hopes of a fast payout due to market fluctuations

ticker tape: the method used to transmit stock prices over telegraph lines using a paper strip that ran the stock symbols and their prices through a machine that made a ticker sound

Candela Citations

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by: Caileigh Abente for Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- US History. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: http://openstaxcollege.org/textbooks/us-history. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- The Crash of 1929. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/NgBFhmUc@11.2:-JpHLQEb@2/11-12-%F0%9F%94%8E-The-Crash-of-1929. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/36004586-651c-4ded-af87-203aca22d946@11.2

- The Great Depression. Provided by: The American Yawp. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/text/23-the-great-depression. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Herbert Hoover. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Hoover#/media/File:President_Hoover_portrait.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Hoover's inauguration. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Hoover#/media/File:Taft_Hebert_Hoover_Oath.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Herbert Hoover, address delivered in Denver, Colorado, 30 October 1936, compiled in Hoover, Addresses Upon the American Road, 1933-1938 (New York, 1938), p. 216. This particular quotation is frequently misidentified as part of Hoover’s inaugural address in 1932. ↵