Learning Objectives

- Describe Kennedy’s early presidency, including the Kennedy administration’s “flexible response” to the Cold War

- Explain Vietnam’s connection to the Cold War and U.S. involvement in Vietnam during Kennedy’s presidency

Figure 1. Major political events of the 1960s.

In the 1950s, Dwight D. Eisenhower presided over a United States that prized conformity over change. Although change inevitably occurred, as it does in every era, it was slow and greeted warily. By the 1960s, however, the pace of change had quickened and its scope broadened, as restive and energetic waves of World War II veterans and baby boomers of both sexes and all ethnicities began to make their influence felt politically, economically, and culturally. No one symbolized the hopes and energies of the new decade more than John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the nation’s new, young, and seemingly vigorous president. Kennedy had emphasized the country’s aspirations and challenges as a “new frontier” when accepting his party’s nomination at the 1960 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, California.

The New Frontier

The son of Joseph P. Kennedy, a wealthy Boston business owner and former ambassador to Great Britain, John F. Kennedy graduated from Harvard University and went on to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1946. His political career was bolstered by his father’s fortune, but also his reputation as a war hero who had saved the crew of his patrol boat after it was destroyed by the Japanese. In 1952, he was elected to the U.S. Senate for the first of two terms. For many, Kennedy represented a bright, shining future in which the United States would lead the way in solving the most daunting problems facing the world.

Kennedy’s popular reputation as a great politician undoubtedly owes much to the style and attitude he personified. He and his wife Jacqueline conveyed a sense of optimism and youthfulness. “Jackie” was an elegant first lady who wore designer dresses, served French food in the White House, and invited classical musicians to entertain at state functions. “Jack” Kennedy, or JFK, went sailing off the coast of his family’s Cape Cod estate and socialized with celebrities. The charmed, almost regal atmosphere surrounding the Kennedy White House was often called “Camelot” by observers in the press, after a musical set in Arthurian times that was popular in the early 1960s. Few knew that behind Kennedy’s healthful and sporty image was a gravely ill man whose wartime injuries caused him daily agony.

Figure 2. John F. Kennedy and first lady Jacqueline, shown here in the White House in 1962 (a) and watching the America’s Cup race (a sailing competition) that same year (b), brought youth, glamour, and optimism to Washington, DC, and the nation.

Nowhere was Kennedy’s style more evident than in the first televised presidential debate held on September 23, 1960, between him and his Republican opponent, Vice President Richard M. Nixon. The debate focused on domestic policy and provided Kennedy with an important moment to present himself as a composed, knowledgeable statesman. In contrast, Nixon, an experienced debater who faced higher expectations, looked sweaty and defensive. (Nixon had recently been hospitalized for an infected knee injury, which contributed to his gaunt appearance.) Seventy million viewers watched the debate on television; millions more heard it on the radio. Radio listeners famously thought the two men performed equally well, but the TV audience was much more impressed by Kennedy, giving him an advantage in subsequent debates.

Link to Learning

View television footage of the first Kennedy-Nixon debate at the JFK Presidential Library and Museum.

Kennedy did not appeal to all voters, however. Many nativists feared that because he was Roman Catholic, his decisions would be influenced by the Pope. Even traditional Democratic supporters, like the head of the United Auto Workers, Walter Reuther, feared that a Catholic candidate would lose the support of Protestants. Many southern Democrats also disliked Kennedy because of his liberal position on civil rights. To shore up support for Kennedy in the South, Lyndon B. Johnson, the Protestant Texan who was Senate majority leader, was added to the Democratic ticket as the vice-presidential candidate. In the end, Kennedy won the election by the closest margin since 1888, defeating Nixon with only 0.01 percent more of the record sixty-seven million votes cast. His victory in the Electoral College was greater: 303 electoral votes to Nixon’s 219. Kennedy’s win made him both the youngest man elected to the presidency and the first U.S. president born in the twentieth century.

Kennedy dedicated his inaugural address to the theme of a new future for the United States. “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country,” he challenged his fellow Americans. His lofty goals ranged from fighting poverty to winning the space race against the Soviet Union with a moon landing. He assembled an administration of energetic people, nearly all of whom were also born in the twentieth century, assured of their ability to shape the future. Dean Rusk, a diplomat who specialized in Asian affairs, was named secretary of state. Robert McNamara, the former president of Ford Motor Company, became secretary of defense. Kennedy appointed his younger brother Robert as attorney general, much to the chagrin of many who viewed the appointment as a blatant example of nepotism.

Kennedy’s domestic reform plans remained hampered, however, by his narrow victory and lack of support from members of his own party, especially southern Democrats. As a result, he remained hesitant to propose new civil rights legislation. His achievements came primarily in poverty relief and care for disabled Americans. Kennedy’s administration expanded unemployment benefits, piloted the food stamps program (today called SNAP), and extended the National School Lunch Program to more students. In October 1963, the passage of the Community Mental Health Act increased support for public mental health services.

Kennedy and the Cold War

Kennedy focused most of his energies on foreign policy, an arena in which he had been interested since his college years and in which, like all presidents, he was less constrained by the dictates of Congress. Kennedy, who had promised in his inaugural address to protect the interests of the “free world,” engaged in Cold War politics on a variety of fronts.

The Space Race

For example, in response to the lead that the Soviets had taken in the space race in 1961 when Yuri Gagarin became the first human to successfully orbit the earth, Kennedy urged Congress to not only put a man into space but also land an American on the moon, a goal finally accomplished in 1969.

This investment facilitated a variety of military technologies, especially the nation’s long-range missile capability, resulting in numerous profitable advances for the aviation and communication industries. It also funded a growing middle class of government workers, engineers, and defense contractors in states ranging from California to Texas to Florida—a region that would come to be known as the Sun Belt—becoming a symbol of American technological superiority. At the same time, however, the use of massive federal resources for space technologies did not change the economic outlook for low-income communities and underprivileged regions.

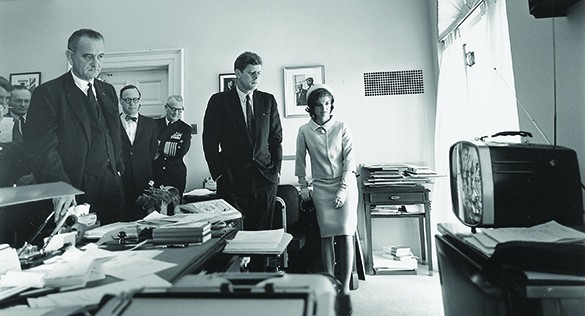

Figure 3. On May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American to travel into space, as millions across the country watched the television coverage of his Apollo 11 mission, including Vice President Johnson, President Kennedy, and Jacqueline Kennedy in the White House. (credit: National Archives and Records Administration)

Soft Power

To counter Soviet influence in the developing world, Kennedy supported a variety of measures. One of these was the Alliance for Progress, which collaborated with the governments of Latin American countries to promote economic growth and social stability in nations whose populations might find themselves drawn to communism. Kennedy also established the Agency for International Development to oversee the distribution of foreign aid and founded the Peace Corps, which recruited idealistic young people to undertake humanitarian projects in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. He hoped that by augmenting the food supply and improving healthcare and education, the U.S. government could encourage developing nations to align themselves with the United States and reject Soviet or Chinese overtures. The first group of Peace Corps volunteers departed for the four corners of the globe in 1961, serving as an instrument of “soft power” (influence through appeal and attraction without coercion) in the Cold War.

Flexible Response

Kennedy’s various aid projects, like the Peace Corps, fit closely with his administration’s defense strategy of flexible response, which Robert McNamara advocated as a better alternative to the all-or-nothing defensive strategy of “mutually assured destruction” favored under Eisenhower’s New Look strategy. Eisenhower’s strategy had focused on building up nuclear weapons and fighting off communism using the threat of massive retaliation (essentially, the promise that the U.S. would respond with much greater force in the event of an attack); this meant that while increasing military spending, Eisenhower reduced the size of the conventional military, budgeting more towards nuclear arms and less for conventional troops.

While Kennedy continued to build up nuclear weapons as a threat against the Soviet Union, the flexible response plan was to develop different strategies, tactics, and even military capabilities to respond more appropriately to small or medium-sized insurgencies, and political or diplomatic crises. This would enable the United States to respond to aggression across the spectrum of war instead of focusing only on the prospect of nuclear confrontation. One component of flexible response was the Green Berets, a U.S. Army Special Forces unit trained in counterinsurgency—the military suppression of rebel and nationalist groups in foreign nations. Much of the Kennedy administration’s new approach to defense, however, remained focused on the ability and willingness of the United States to wage both conventional and nuclear warfare, and Kennedy continued to call for increases in the American nuclear arsenal.

Link to Learning

In this short clip, you can watch an interview with defense secretary Robert McNamara as he and others talk about the flexible response strategy, which diversified the U.S. military strategy beyond just the use of nuclear weapons. In the clip, McNamara explains how that idea was not initially well-received by NATO powers.

Try It

Vietnam

In the 1940s and 1950s, nationalist independence movements fought to decolonize Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. In Southeast Asia, movements like Vietnam’s Viet Minh, under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, had strong Communist sympathies. The Soviet Union had traditionally supported movements to break away from the old European empires, and many nationalist leaders found insight in Lenin’s belief that imperialism was the highest stage of capitalism. Fearing the rise of communism in Southeast Asia, in 1950 the Truman administration sent funds, arms, and advisors to help France defeat the Viet Minh and retain its colonial holdings.

Watch It

This video details some of Ho Chi Minh’s life. Watch it to learn about his rise to power and his influence in North Vietnam, which would eventually lead to the conflict between the communist North and the U.S.-based South during the Vietnam War.

Reunification did not materialize, however. In the south, Diem conducted a fraudulent election in 1955 and proclaimed himself President of the Republic of Vietnam. He canceled the 1956 election scheduled by the Geneva Accords and began persecuting Communists and supporters of Ho Chi Minh, who remained in control of the north. The conflict between North and South Vietnam reignited during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The United States, fearing the spread of Communism under Ho Chi Minh, supported Diem, despite resistance to his government among South Vietnamese farmers, students, and Buddhists. Fearing Vietnam would instigate a domino effect in the region, The U.S. deemed it necessary to aid Diem, assuming he would create a democratic, pro-Western government in South Vietnam. The domino theory is a geopolitical theory that was prominent during the Cold War which posited that if one country in a region came under the influence of communism, then the surrounding countries would follow in a domino effect.

Figure 4. Following the French retreat from Indochina, the United States stepped in to prevent what it believed was a building Communist threat in the region. Under President Kennedy’s leadership, the United States sent thousands of military advisors to Vietnam. (credit: Abbie Rowe)

When Kennedy took office, Diem’s government was faltering. Continuing the policies of the Eisenhower administration, Kennedy supplied Diem with money and military advisors to prop up his government. By November 1963, there were sixteen thousand U.S. troops in Vietnam, training members of that country’s special forces and flying air missions to disrupt North Vietnamese forces and supply routes. A few weeks before Kennedy’s own death, Diem and his brother Nhu were assassinated by South Vietnamese military officers after U.S. officials indicated their support for a new regime.

Try It

Review Question

Glossary

Alliance for Progress: an initiative developed by President Kennedy’s administration and Latin American leaders to promote economic development and the growth of democracy in Latin America

counterinsurgency: a new military strategy under the Kennedy administration to suppress nationalist independence movements and rebel groups in the developing world

domino theory: a prominent geopolitical theory during the Cold War which posited that if one country in a region came under the influence of communism, then the surrounding countries would follow in a domino effect

flexible response: a military strategy that allows for the possibility of responding to threats in a variety of ways, including counterinsurgency, conventional war, and nuclear strikes

Peace Corps: a federally-funded volunteer program, established by President Kennedy in 1961, with the goal of promoting social and economic development around the world